Virtual Environments: A Review of Whakapī

Dilohana Lekamge considers the adaptation, digital technologies and customary practices in the work of Kereama Taepa.

Dilohana Lekamge considers the adaptation, digital technologies and customary practices in the work of Kereama Taepa.

Whakairo can be used as both a noun: a carving – and a verb: to carve. Iro meaning maggot combined with whaka meaning ‘to cause to something to happen’ describes the action of gradually taking material away through the carving process just as a maggot will eat through live or decaying matter and create crevices. However in Whakapī, a recent exhibition at Pātaka Art + Museum, artist Kereama Taepa cleverly replaces ‘iro’, with ‘pī’ – meaning bee. Unlike a maggot, a bee builds up structures using a repeated hexagonal pattern to do so, a processed also mimicked by 3D printing.

It is this wordplay which foreshadows Taepa’s intelligent fusion of Māori customary practice, retrogaming characters, sci-fi references and state-of-art technology as seen in Whakapī. Picking up aspects from very different worlds Taepa produces an interactive space equipped with both physical and virtual elements.

Taepa (Te Arawa and Te Ati Awa) is an internationally exhibited artist with a very rich and varied creative career spanning art, design and fashion. He gained a Masters of Māori Visual Arts from Toioho ki Āpiti, Massey University and he currently teaches on the Bachelor of Creative Technologies at Toi Ohomai Institute of Technology, Rotorua.

When you walk into the gallery space you see a number of 3D printed sculptures hanging on either side of the space. On the right side are white plastic wheku, facial representations, with characters from Tetris, Star Wars and Pac Man intricately printed onto their surface. On the opposite wall are the Apple icon, more Pac Man characters and Mickey Mouse, symbols of significant Western technological advances. The viewer is prompted to consider the correlation between these globally recognised tech symbols and whakairo.

The viewer is prompted to consider the correlation between these globally recognised tech symbols and whakairo.

While studying Fine Arts at university, I came across Wayne Youle’s Often Liked, Occasionally Beaten – a series of bright multi-coloured resin tiki placed on lollipop sticks and Fiona Pardington’s series of photographed hei tiki recovered from Museum archives across Aotearoa, two series which also incorporated whakairo. Youle addressed the commercialisation of Māori art and artefacts by building kitsch-like objects that used patterns from whakairo of hei tiki. Pardington’s study utilised the gelatin silver process of photographic printing to make hei tiki that were kept in storage for many years to show their spiritual qualities through the prints which seemed to almost glow through the photograph. In studying these works as a non-Māori my main concern was how well these objects and practices were respected and how to protect them from being further commodified. I did however seem to overlook what these new objects, made by Youle and Pardington, contributed to contemporary art. Funnily enough, in the space next to Whakapī was The hoe and the hōiho an exhibition by Wayne Youle, which was an installation of selected items from Pātaka’s collection. The close proximity of these displays made my own ignorance more apparent together they show how contemporary Māori art can serve both purposes of protecting and displaying these art forms while simultaneously pushing what Māori art is.

As an exhibition Whakapī did just that. On a closer inspection the tech icons have printed whakairo patterns derived from Taepa’s iwi, Te Āti Awa and Te Arawa, whose stylistic differences appear distinct. For example the zigzag pattern on the Apple icon reflects the taratara ā kae design iconic to Te Arawa in the Rotorua region. Usually carved onto pātaka that functioned as elevated storehouses for food stuffs and valuable items – the carving of which is particularly important as it indicated prosperity and how well its contents was able to provide to its community.

Robert Janhke[1], one of Taepa’s mentors at Toioho ki Āpiti, Massey University describes whakairo as originating from a supernatural world and operates in a spiritual realm that functions differently to design from the human world. This connects to the other work of Whakapī, Infinite Possibilities, a virtual reality waharoa. Waharoa are carved gateways, and in Infinite Possibilities, Taepa used VR technology to depict the otherworldly origin of whakairo, pointing to the transcendence that waharoa mark.

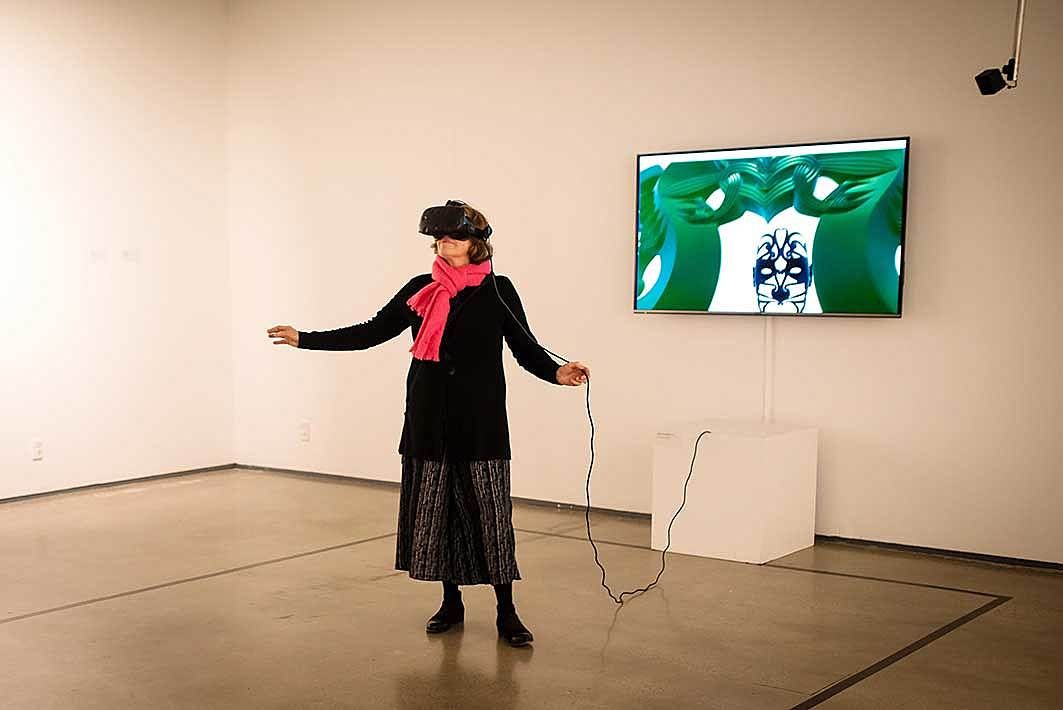

On the floor of the exhibition space is a black square outline marking the area in which the viewer can walk while wearing the virtual reality goggles which bring to life the waharoa. The goggles unlock a completely different perspective of the space. VR goggles and headsets have become a significant part of contemporary gaming and digital experience. Yet to truly stand the test of time, they are becoming more accessible novelty items as manufacturers find cheaper ways to make them. Though VR headsets have been made as early as the 1990’s they have gained popularity in the last few years which has amplified possibility for how we can escape our reality by placing our sights and sounds in a different world without having to leave the room you stand in.

Taepa uses the VR goggles as a tool to access a digital counterpart of the exhibition where the waharoa becomes the main feature. Waharoa are commonly erected as a gateway to fortified pa marking a point of entrance and exit often covered with elaborately carved representations of Atua and ancestors. Historically palisades would border the terraces, so anyone who wanted to enter must go through the waharoa to do so. But the waharoa could be closed off when desired in order to avoid any attackers from entering. Similarly, some waharoa were carved to represent Tūmatauenga (God of War), which warriors would pass under before they entered battle marking their commitment to Tūmatauenga.

Once the goggles are on you see the large dark green waharoa which appears to hover in front of the viewer high enough so it can be walked under. It floats in a blank virtual plane. If you walk under the waharoa and turn back to go back a spider web is suddenly underneath the arch, as if you cannot walk back through. The spider web which appears once you turn to walk back under imitates how many warriors admitted that they may not return from battle, so they would not be able to enter the pā again. It similarly reflects how the gateway would be blocked for those who may want to attack the pā.

Though it is an elevated spiritual transcendence that the waharoa signifies the goggles offer a similar shift from one realm to another. The waharoa has its purposeful restrictions in order to protect the pā and all that it holds, but the restrictions that the goggles pose are inevitable faults in the technology as it does not physically transport the viewer to another space nor can it provide all of the attributes that reality does. Inevitably, where the goggles falter a waharoa succeeds, as its point of transcendence is both physically and spiritually tangible, proving that these customs have survived through thousands of years providing physical protection.

Māori, like all people across the world are a part of a globalised society. And as Māori have constantly adapted over time and through generations, so have their creative forms within which their customs are closely held. Taepa reminds us of this by making clear the distinct whakairo practices between iwi across Aotearoa, by the placing different techniques of whakairo next to each other reminding us that all carving does not look the same, nor can its patterns only be applied to the customary materials of bone, wood or stone.

Pātaka Art + Museum is located in the middle of Porirua city, which has a large Māori, Pasifika and immigrant population that gives this institution an audience that sets it apart from its contemporaries in less culturally diverse areas. It is also the only contemporary art museum of its kind in this area. For this reason it becomes the perfect platform to exhibit art made by practitioners whose cultures are also inadequately represented. As I grew up in a neighbouring suburb to Porirua, I am familiar with the city’s willingness to celebrate its diversity.

Whakapī confronts an expectation of a universal visual Māori language, instead highlighting a tool to show cultural difference and adaptation

As a viewer I needed guidance from the accompanying texts and curatorial staff to understand the complexity and significance of the work. I am unsure if I will ever be able to understand it entirely because it is impossible comprehend the intricacies of a culture that is not your own. On a base level, as a minority, I can comprehend the need to correct social misrepresentation of one's own culture, but not to the same extent as Maori in New Zealand. This exhibition reveals the potential to expand conversations about culture in a way that doesn’t need to be verbal and a space where misconceptions can be corrected. By creating art today we can simultaneously represent and shield what is important to our people and also contribute to our growth. Whakapī makes it easier for a variety of viewers to learn about Māori culture in a space that isn’t dominated by Eurocentricity, in context that isn’t purely historical.

Whakapī confronts an expectation of a universal visual Māori language, instead highlighting a tool to show cultural difference and adaptation. Taepa bridges the gap between pre-colonial forms and imagery learned from pop culture to highlight Māori resilience, rich histories and adaptation. Kereama Taepa displays the ingenuity of Māori art – a form that has continuously had to adapt to the physical and cultural changes that took place spite of attempts diminish its value.

Kereama Taepa

20 May 2017 – 13 August 2017

Pātaka Art + Museum

All images courtesy of the artist and Pātaka Art + Museum

[1] JAHNKE, ROBERT. "KO RŪAMOKO E NGUNGURU NEI: READING BETWEEN THE LINES." The Journal of the Polynesian Society 119, no. 2 (2010): 111-30. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20790136.