The Lives Of Others: Serial, There and Here

Saziah Bashir and Diane White on Serial

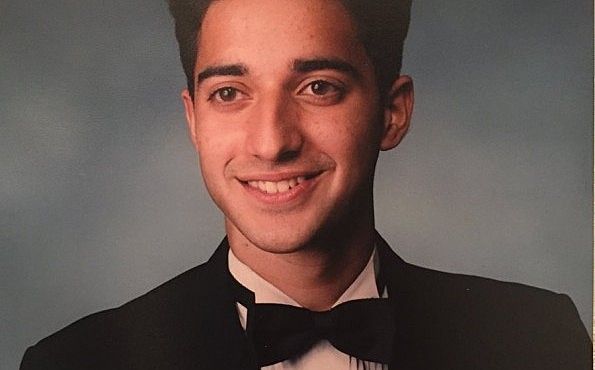

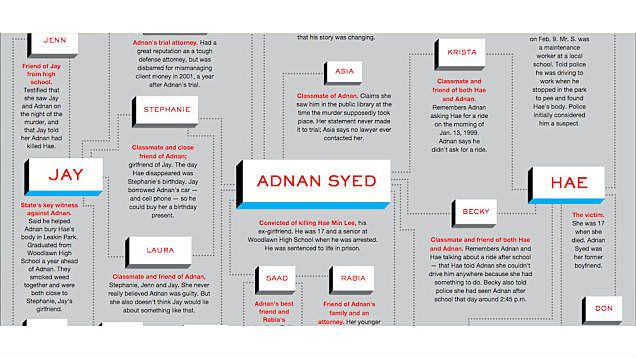

Given the hype, you would be forgiven for thinking that neither podcasts nor whodunit crime thrillers existed before This American Life’s hit series Serial. The story of 17-year-old high schooler Adnan Syed, who was found guilty by a jury of the murder of his ex-girlfriend, Hae Min Lee, and who has insisted on his innocence ever since, has now been heard by millions of people across the world. It’s a seemingly unprecedented level of success for both a podcast, and for a “true-crime” thriller outside of the kind of genre fiction that gets advertised on the side of buses.

As two writers who work in the law, it’s hardly surprising we were captivated by Adnan’s story. But equally, we were drawn in by the vehicle that story rode in on: a 12 episode podcast routinely drip-fed directly into our ears, like a weekly gossip session with an old, close friend, each development more juicy than the last. In doing so, we were inexorably attracted by the constant lures of narrative: the way Koenig and her team shaped and directed the story, the stereotypes on which she played, the tropes on which she relied. We were also interested in the way Serial reflected – or failed to reflect – reality: the realities of criminal trials and courtrooms, and the plight of those who are wrongly convicted.

Perhaps what struck us most was it isn’t an exceptional story in and of itself. In fact, this tale or at least variations have been repeated countless times, over many centuries, in many ways. It’s one being played out every day in courtrooms around the world. Important doesn’t mean unique – not in the United States, not in New Zealand, not anywhere.

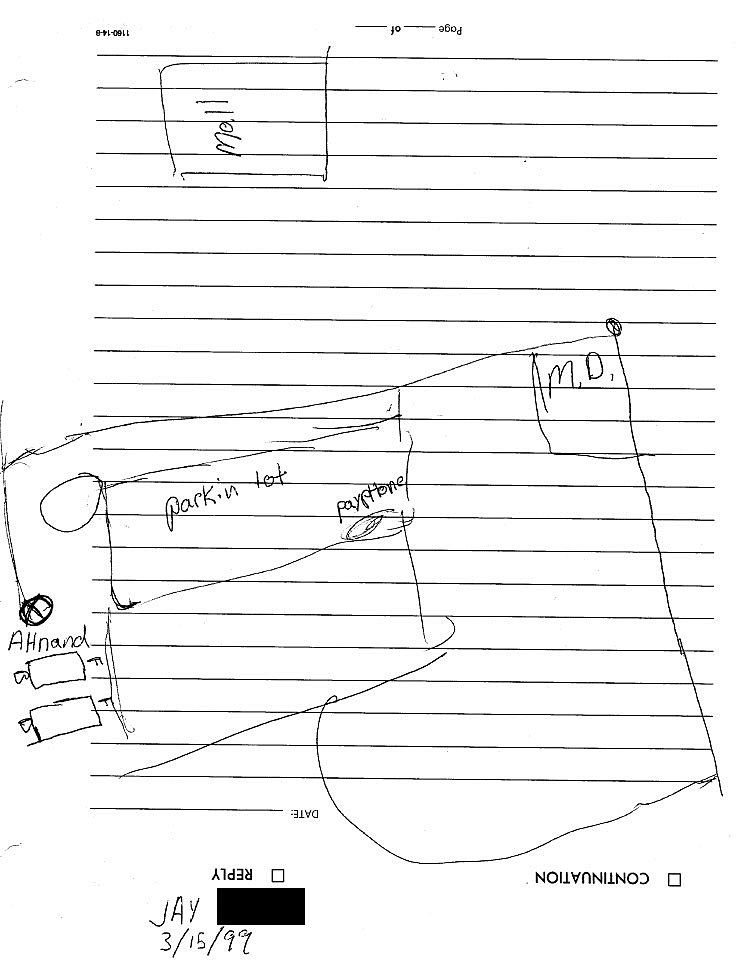

Going through law school and working in the law didn’t leave you above or ahead of Serial, either. Like every other listener, we went back and forth – testing the case, playing the role of judge, jury, prosecution and defence all rolled into one. We, too, would come back to the same questions as Koenig: If Adnan didn’t do it, why would the key prosecution witness, Jay, make this whole thing up? Who, if not Adnan, had a motive? But there’s reasonable doubt… and on and on.

But, for us, the answers to those questions are almost irrelevant. Serial isn’t about Koenig or anyone else coming to a verdict of guilt or innocence. The relative strengths and weaknesses of Adnan’s case are something we’ll leave to the other five million self-appointed detectives out there trying to solve this case – and, perhaps one day, an appeal judge.

As its protagonist's supporters celebrate his hearing to seek leave for appeal this June, let’s talk about the story Koenig tells us, as distinct from the case of Adnan Syed v State of Maryland: an unexceptional story of exceptional popularity that has us talking, debating and speculating even after we’re done listening to it being told.

Saziah Bashir

I want to clarify that emphasising that the story of Hae’s murder isn’t unique is not intended to diminish or belittle the importance of it or the lived experiences of the people involved. When it comes to the loss of life and liberty, there are no small stories. But women die at the hands of their partners, spouses, boyfriends, lovers or exes all the time. When a woman goes missing, as Hae did, and her body is found several weeks later, as Hae’s was, it’s almost inevitable that the investigation would encompass current or former boyfriends as suspects. It is unsurprising that the Police honed in on Adnan Syed.

It’s in Adnan that the State, (and Serial’s first season) found a goldmine. Adnan, for me, is the most interesting character in this story, my quickest route into some of the themes that I find most compelling about the whole saga: Adnan’s race and religion, and personality, and how each fed both the narrative of the State’s case and Koenig’s subsequent investigation.

The prosecution case against Adnan, in a nutshell, was that he killed Hae out of revenge. She broke his heart after he had invested in their relationship at the expense of his culture, religion and familial expectations. But he was a model young member of his Muslim community outside of the relationship? Grist to the mill: the State used this ‘double life’ as proof of his ability to lie, of an inherently untrustworthy nature.

If you’re a jobbing writer or journalist looking for a hook, a stack of excellent tropes have already presented themselves: a murder mystery, an unfathomable Other in a leading role, exotic notions of besmirched honour and pride, young love and revenge and, finally, the shit teenagers get up to - the last of these providing a stabilising sense of familiarity to poignantly offset the unsettling sensation of too much time around the unknown.

Where the prosecution case really falls flat for me is that assertion of Adnan’s duplicity, that his partying, drinking and dating while playing the good little Muslim kid at home indicated something sinister. Because what almost any good little Muslim kid could tell you is that most of us do this exact thing. We lie to our parents. We do it a lot.

It’s been a while since I’ve been a teenager, but I remember the intricate web of lies I’d weave, co-conspirators and alibis at the ready, for every party I wanted to attend. I remember specifically promising not to dance with boys at my seventh form ball, and it’s best not to dwell on what subsequently went down to "Ignition (Remix)" or the lengths taken to make sure no talk reached home.

This wasn’t limited to the Muslim kids. I had Indian friends with Hindu parents, Sri Lankan friends with Christian parents, Chinese friends with Mormon parents and Pakeha friends with paranoid parents. They were all masters of subterfuge to varying degrees, because all parents disapprove of or fear certain things their kids may do. Migrant parents, arguably, disapprove of more, because the tension between original and adopted cultures and how it blurs once-fixed boundaries, lines between acceptable and unacceptable public and private behaviour.

The prosecution’s assertions boiled down to this: Adnan Syed was guilty of being the very definition of a teenager. But in Adnan Syed’s case, this was not trivial teenage behaviour, but sinister, because he was a Muslim kid, and they’re not like regular kids. They’re not like the kids the jury would have known. These Muslims, they believe in honour killings, they hurt their women, who knows what they’re capable of?

Even pre-9/11 the media would make much of instances of honour killings than, say, domestic violence of the “regular” variety. Brutalities against women or practices such as female genital mutilation, often were, and still are, conflated with the Islamic faith and the practices of Muslims at large rather than identified as endemic to certain regions and a result of complex socio-economic and cultural circumstances within patriarchal societies.

Comments made by the jurors who spoke to Koenig confirm the success of this strategy. One juror alleges he had seen other Muslim men of his acquaintance treat “their women” badly, while Adnan is repeatedly referred to as Middle Eastern, an especially loaded designation in an American context. An inaccurate one, too - pointing out the difference between being South Asian and Middle Eastern is not pedantry, but the difference is perhaps irrelevant if you hold the same prejudices against brown immigrant men of the Muslim faith regardless of which country they hail from.

Adnan was an American born man - a boy, really - of Pakistani ethnicity. But that doesn’t fit the narrative of the Other that was so important here.

When she first looks into Adnan’s case, Koenig compares him to Othello in her very first impression of the story at hand, “not a Moor exactly, but a Muslim all the same.” Thankfully, Koenig doesn’t try to extend the analogy, but it does have the implication that the prosecution’s lead witness and Adnan’s sometime friend, Jay, is the story’s Iago. Not in the sense that he’s some arch-villain that some extreme interpretations of Serial would have you believe, but in the sense that the narrative leaves his motives troublingly opaque and unknowable.

But Jay’s not some enigmatic force of fiction - he adds an extra layer to the issue of race and how it played out in this case. No matter how much his story changed, or how many of the things he said seemed odd, there were two things Jay said to the police that rang very true.

First: he was scared, and as a young black male recreationally dealing marijuana in Baltimore, he should have been. It’s no secret black males are disproportionately prosecuted for drug crimes: Jay’s own fears in this regard were probably well-founded.

Secondly: when the police question Jay over why he didn’t go to the authorities sooner, he is never more believable than when he says the thought simply did not cross his mind. Bluntly: “I could be getting shot at and I wouldn't be like ‘let's call the cops’”. You could call this prophetic, but ‘prophetic’ means accurately predicting something that will happen in the future, and it’s not like this kind of racial violence has ever waned or stopped.

It cuts chillingly to the core of how race is germane to the prosecution and conversation about crime and the criminal justice system there. Systemic prejudice can breed distrust of authority and produce counterintuitive reactions that are easily cast in a suspicious light when we play armchair detective from the comfortable distance of hindsight.

There’s a final, not insignificant quirk to the race issues at play. In Episode 10, Koenig makes an offhand comment about the majority black jury finding Jay a credible witness. Adnan, on the other hand, remained the Other. What Serial’s diverse listenership makes of the diverse characters in Serial’s story adds a whole other dimension to the reception of the phenomenon.

Meanwhile, there's the matter of the delivery of the story itself. There was something about the way Koenig delivered the story, like a friend in your ear updating you about her day at work, that heightened the intimacy of the experience. Koenig’s narrative can leave you feeling like you’re in on the clique: making small asides about how there was too much reading so she made Dana do it, or divulging personal information about her own silly behaviour as a teenager. Even the fact that Sarah talks to Adnan mainly on the prison phone, meaning we mostly hear from him as if we’re on the phone to him ourselves, takes our “closeness” to the storytelling to an entirely new level. As with any big cultural obsession these days, Adnan now has his own fangirls out there.

Serial remains many things – surprising, exciting, but above all, consummately, constantly relatable. There’s an abiding sense of “this is an amazing story from a friend you haven’t caught up with in years” and it’s Koenig that, mid-murder investigation, throws in quirky phrases like “there’s a shrimp sale at the Crab Crib”, immediate taglines for fans of the show. It’s the illusion of spontaneity in a production we know, rationally, couldn’t have been so casual. Every editorial decision and production decision is deliberate.

And Koenig plays this up and highlights her process – her doubts, her reaction to the discoveries – which we generally encounter as a post-production script, Koenig forges a bond with the audience this way - willingly or inadvertently, we trust her neutrality in this, her purported lack of bias.

It’s a dangerous stance to take in the consumption of any piece of journalism. We examine Adnan’s duplicity, assess how much of his affability is performative, but we never consider Koenig’s. We forget that every piece of information she chooses to share or not to share, the order they appear, involved a judgement call. We can’t know what we’re not told, so we don’t know what we don’t know. We forget that she’s not actually that friend on the phone.

Much keyboard energy has already been expended on the ethics of Koenig’s endeavour. I won’t repeat that exercise, but there are a number of issues raised that I do find compelling: As a white interloper in a community of colour, is Koenig equipped to deal with those issues with sensitivity? Is it appropriate that she casts doubts on the character of the black key witness, while playing saviour to Adnan? And what of the genuinely silent voice in Serial: Hae, conspicuous only by her absence from what’s also her story, no one from her family willing or able to participate? Racially, and in terms of gender, is Serial exploitative? Was this even Koenig’s story to tell?

The show could not be accused of sensationalizing its tragic subject material, and it certainly isn’t murder porn akin to many similarly themed though well less executed “mystery documentaries.” But although Koenig’s enquiry was more subtle, more nuanced, could producing Serial perpetuate a collective inclination best not indulged? Hae remains dead and Adnan, pending possible administrative appeals of appeals, remains in prison. What purpose did Serial serve except its own? It titillated us and we rewarded it with our time and attention, quid pro quo.

I’ve repeatedly compared our engrossment with Serial to the consumption of crime fiction. This isn’t meant to be crass and insensitive by trivializing a real tragedy and comparing it a work of fiction, or suggesting audiences don’t know the difference, but to reinforce the commercial mass success of the thing. It had all these elements of great literary works, (the Shakespeare allusion feels a little off-key, but it’s there). It’s the most popular crime fiction tropes delivered in a way that seems innovative, but works because it’s essentially the oldest storytelling method of all time – someone telling you a story. And we embraced it. Plenty of remarkable stories are told once and then go into the night: we, the audience, were complicit in making Serial’s ordinary story an extraordinary success.

Di White

From a young age, we learn there are two types of stories: fact and fiction. Made-up stories about fairies and dragons and wizards are fiction, while serious stories about war and famous sportspeople are fact. They’re depicted as two, neat categories with no overlap or crossover. So when we hear a story that challenges our assumptions about reality, the first question people often ask is whether the story is true – whether we are reading or watching or, in this case, listening to fact and fiction.

I type: ““Is Serial…”

“Is Serial podcast a true story”, “Is Serial true”, “Is Serial real” and “Is Serial a true story”, Google throws back at me. It seems, for many people, the case seemed too good, or perhaps too bad, to be true.

As Saziah explained, the story of Hae Min Lee’s death is not in and of itself exceptional, but its popularity and its reach truly is. Serial found its way into the ears of people who simply do not think about crime and justice, innocence and guilt, on a daily basis. People who are in prisons are there because they did a bad thing, and through a fair process headed up by a judge they have been punished for their actions. That is non-fiction, my six-year-old self would confidently explain.

But for many of the people listening to Serial, the story of a man who was perhaps wrongly accused, prosecuted and then imprisoned starts to look a lot more like fiction. To think that innocent people habitually go to jail outside of John Grisham books throws up all kinds of possibilities: there could be innocent people – people who did nothing and were simply at the wrong time or place (or weren’t known to be in any place at the critical time, such was the case with Adnan) – in prison right now.

And the next logical thought: this means an innocent person like me, or even someone I love, could be put in prison one day without having committed the crime. For many, those assumptions simply cannot be true: too much depends on what we’ve set up about how crime and punishment works for them to be fictions.

It doesn’t help that where we do see those media instances of false accusations and false imprisonment, it’s with a heavy dose of melodrama: people are framed, there’s a cover-up or conspiracy, and all at the hands of an arch-fiend. We’re never encouraged to imagine that being accused of, and subsequently found guilty of, murder could happen to anyone, and that the process could be awfully banal.

We’re not interested in arguing for whether Adnan’s story is true: if you’ve listened to the podcast, no doubt you’ve considered that for yourself. But let there be no question in your mind: the story of a man who is wrongfully convicted and sent to jail is a “true story”. It happens – in the US, in New Zealand and all around the world. In fact, within the first minutes of the first episode of Serial, one name came to mind: Teina Pora.

As many New Zealand readers will know, Teina Pora was found guilty of the murder of Susan Burdett, who was brutally murdered in her Papatoetoe home in 1992. He, like Adnan, was around the age of 17 at the time he was convicted, two years after Burdett’s murder in 1994. Pora served 20 years for the murder before being released on parole in 2014.

While Pora and Syed were around the same age at the time they faced conviction, the similarities between the two pretty much stop there. Serial depicts Syed as intelligent and attractive – a young man with a bright future ahead of him (even if he did smoke a little pot). Pora, on the other hand, was a young gang prospect with foetal alcohol spectrum disorder, and around the time of the murder had been involved in various non-violent criminal activities.

Unlike Syed, who proclaimed his complete innocence from Day One, Pora eventually told the Police (in the course of a 14-hour interview during which he had no lawyer, no less) he had been present at the time of the rape and murder of Burdett, but that he had not committed the crime. His story changed again a number of times before he was charged.

His defence would go on to argue at a retrial that it was another man, serial rapist Malcolm Rewa, who had raped and killed Burdett (Rewa was arrested in 1996, two years after Pora’s conviction, and a DNA test then matched him to semen found at the crime scene). It is now widely thought, and recently argued before the Privy Council in London in an appeal, that it was Rewa who both raped and killed Burdett, and that Pora lied about his presence at the scene of the crime that night.

Why lie about involvement in a crime so serious? To start with, there was $20,000 up for grabs as a reward for information - no small amount in 1994 to a young man with limited options, a baby daughter, and facing threats from gang members. It was suggested that he also thought he might get off unrelated minor charges (he was first brought in on an outstanding warrant for car theft) by showing he was compliant with, even valuable to police. Essentially, his recent defence argues he was young, not of a high intellect, and thought money would get his life on track, so he went to the Police. Instead, he ended up in prison for 20 years.

In the case against Pora’s conviction, like that of Syed, it took a long time and a large number of people saying the same thing before someone started to listen. Like Syed, Pora’s plight was significantly assisted by some exceptional investigative journalism – in this case, from journalists Phil Taylor of the New Zealand Herald and Paula Penfold of TV3’s 3rd Degree (although Taylor and Penfold certainly weren’t afforded a year to research and write the story, the luxury of 12 episodes to tell it, and the significant resources no doubt poured into Serial).

What should be taken from both Pora and Syed’s cases is that they are not isolated. Despite the disparity in resources, these are still cases that we’ve had delivered to us on a plate. They are cases that have benefited from individuals or groups campaigning long and hard for the injustices to be realised. The rest of the time we’re somewhere between oblivious and credulous – we don’t know, don’t care, and assume that our well-resourced and well-balanced justice system gets it right from the police upward.

But I can safely say that as I write this and as you read it: there will be other people in New Zealand prisons who did not commit the crime for which they were convicted. Some of those people may be lucky enough to have people on the outside tirelessly campaigning for them; others will not.

Whether or not you believe Syed, the point to be taken from the very real story that Serial represents is this: the US judicial system is deeply flawed. Both New Zealand and the United States’ systems operate on various ideals and assumptions that simply do not play out in reality. Often this reflects resource constraints: you design a system that relies on every single cog in the wheel turning and working as it was designed to do.

Both in the US and NZ, the maintenance has let the side down: the justice system is full of instances where cogs are broken or simply no longer exist. These ideals also often exist in isolation from reality: a reality where race and religion give rise to discrimination, where police and judges and juries are in no way immune from these prejudices, and where sometimes complexities arise that no legal or political philosophy could anticipate. Essentially, the fundamental principles underpinning these systems have slowly and over time decayed, broken down, or been shown to be unfit for purpose: but the systems have seen little or no change to see reflect these changes.

No longer are the core pillars of a fair trial assumed, for instance. Public funding of defence lawyers (what’s known as legal aid in NZ and other Commonwealth countries) has been under the axe across a number of jurisdictions, with one result being that people face increasingly serious charges before they can obtain a professional standard of representation.

Juries, which rely on the complete fallacy of impartiality, are made up of people with a world of possible prejudicial information at their fingertips. At a more general level, we exist in a political environment obsessed with efficiencies, targets and “getting results”, which puts more pressure on police to resolve crimes and prosecute, more incentive for innocent people to plead guilty and less incentive for the courts to innovate towards more holistic models.

Often, it seems, the judicial system works only for those who created it: the white, the rich, the able, the educated, the well-spoken. Yet when we look at the vast majority of people who appear before the courts, they simply do not fit this profile.

In this regard, Serial was somewhat remarkable – at least unusual. Adnan was the kind of charismatic and garrulous subject who could sustain a 12-episode run – what one could cynically call “talent”. As a former prom king and promising student, he was able to articulate his case in the kind of language and using the kind of logic and reasoning that would resonate with his well-educated audience.

However, many people wrongly imprisoned will be just like the wider prison demographic: over-represented by those who have little or no education, poor communication and literacy skills, or cognitive impairments. Put simply, what we know statistically about those in prison suggests well-educated and articulate people like Adnan are the exception, not the rule.

The accuracy of the story Koenig tells us in Serial is something that will remain the subject of plenty of discussion; the interviews Jay Wild gave over at The Intercept, for example, have stoked an active and sometimes ad hominem debate. This is likely to keep being waged for months, as more people tangentially related to the story come forward and as the efforts to have Adnan’s case overturned continue. Regardless, it will remain a fact that our judicial system – both in the US and in New Zealand – is deeply flawed and constantly at risk of further degradation. The more stories like Serial that see the light of day, the better, as it is through the telling of these small tragedies that force discussion, awareness and change.