The Singing Word: On Shannon Te Ao’s my life as a tunnel

Matariki Williams reflects on whakapapa, reo and loss in Shannon Te Ao's latest exhibition.

Matariki Williams reflects on whakapapa, reo and loss in Shannon Te Ao's latest exhibition.

One of the most fundamental tenets of te reo Māori is the distinction between the A and O categories. These categories reinforce the idea that everything in te ao Māori is relative. The simplest definition of the difference between these two categories is that the A category covers that which you have responsibility, possession, superiority, hierarchy over. Conversely, the O category covers that which you do not have that hierarchy over. For example, you would say ‘āku tamariki’ for ‘my children,’ and ‘ōku mātua’ for ‘my parents.’ This is Māori 101, essential both to understanding the categories grammatically, and to learning what these categories represent in a broader sense within te ao Māori. One of the many times my mind was blown during university reo classes was when we were taught that the very world that we live in is made up of both of those categories: the Māori word for ‘world’ is ‘ao,’ as in the A and O categories, joined together. It is with our language that we simply, and beautifully, articulate our world.

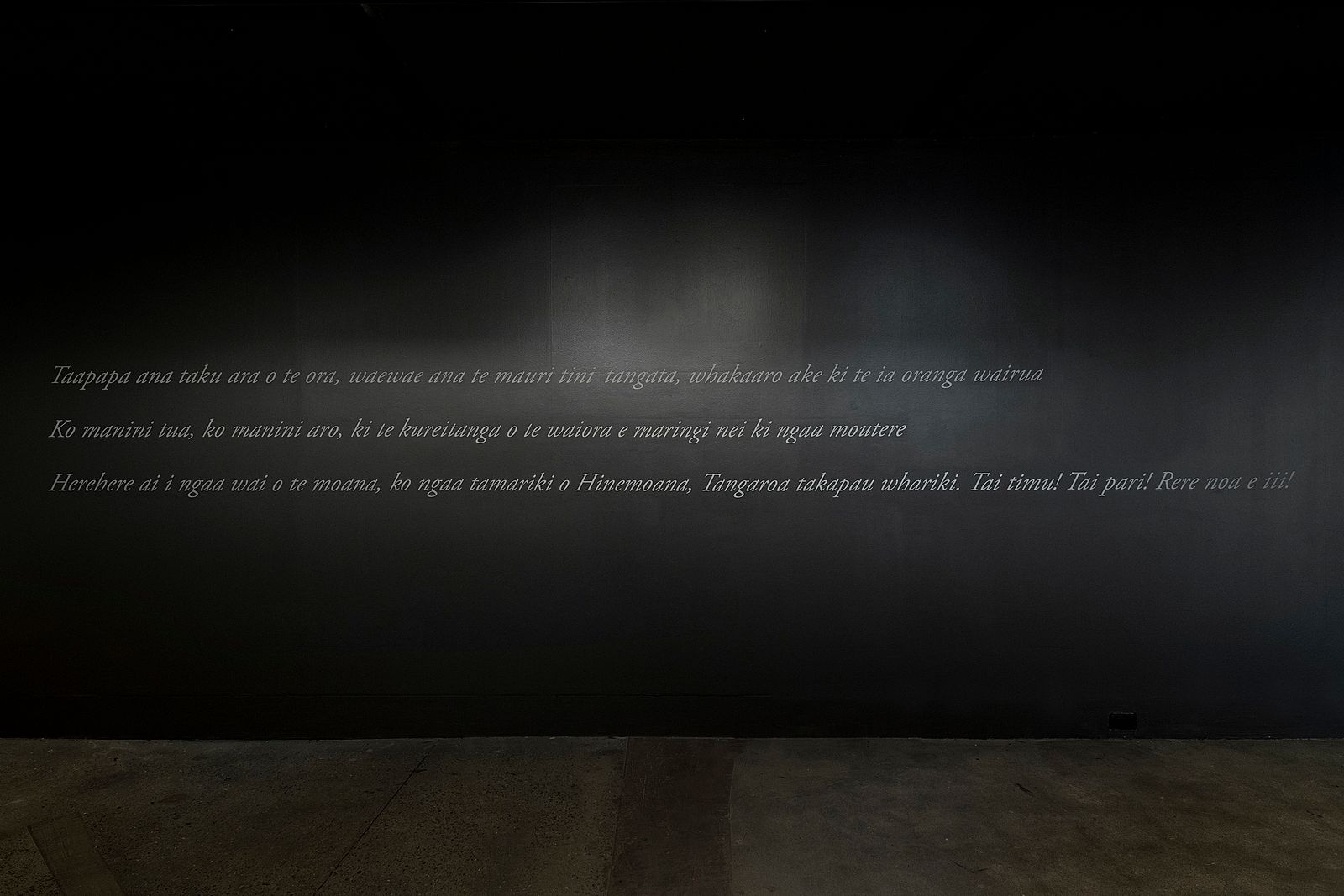

In Shannon Te Ao (Ngāti Tūwharetoa), an artist with the very world in his name, we have someone whose work both layers and unpacks the world with language. Choosing to use te reo Māori in his work is pointed, highlighting the staggering loss of language experienced by Māori and conveying that loss to visitors by presenting a work that most will not understand at its aural value. With his latest video work, my life as a tunnel (2018), the murmur of a mōteatea echoes through The Dowse Art Museum; you hear it before you see it.

Before you reach the video, you must first encounter the words of other artists, Māori and Pākehā, in English and in te reo Māori. In saying that Te Ao’s work highlights language loss, I will explain this by the way I navigated the words of Kurt Komene (Te Atiawa, Taranaki Whānui) in the hallway preceding Nuku Tewhatewha. Komene’s words are all in te reo Māori and were produced in response to a piece of Te Ao’s writing. To access their meanings, I rang my dad. Together, we worked through a translation, attempting to figure out the meanings of words that have multiple entry-points in the context of an artwork in which meanings are amorphous and ultimately irresolvable. Dad ended that part of our phone call by saying, “Now you need to play around with it a bit until it makes sense.”

...I am not surprised that Te Ao has chosen this poetically rich format as a method through which to transmit knowledge, for that is what mōteatea were made for

Dad and I went on to talk about passing on the knowledge of whakapapa, and how he was about to do this with my generation, the way his uncle had done with his. Talking about whakapapa, a multi-layered mnemonic that is richer than its oft-used translation of ‘genealogy,’ circled me back to the layers inherent in Te Ao’s work. In my life as a tunnel, an aspect I feel immensely is that of absence, of the stun that comes with pain. Between my first and second visits to see the show, I read Te Ao’s interview with Megan Dunn where he mentions the death of his father, and after reading it I can’t shake that knowledge from my head. Even though he states that his father’s death isn’t present in the work they’re discussing, With the sun aglow, I have my pensive moods (2017) – a work I haven’t seen – it’s acknowledged that parts of the filming took place in the fields surrounding the urupa his dad is buried in.

I first met Shannon when he sent an enquiry to my place of work, Te Papa Tongarewa, in which he asked to see taonga related to the Ngāti Tuwharetoa tipuna Mananui Te Heuheu Tukino II. This tipuna was a leader in his iwi and died in an 1846 landslide that killed 54 other people. Mananui’s daughter Te Rohu composed the mōteatea He waiata mo te mate ngerengere (Song for a leprous malady), which references personal turmoil including a troubling relationship, the loss of her father and the repercussions of colonial rule. The mōteatea served as inspiration for the two earlier videos in the series my life as a tunnel sits within, Untitled (malady) (2016) and With the sun aglow, I have my pensive moods. Dr Wayne Ngata, a researcher and ardent fan of the mōteatea song form, has referred to mōteatea thus: “Ko te mōteatea te mataaho ki te pā o te hinengaro Māori.” He believes that if people were able to access the richness of mōteatea, they would have a great insight into the Māori world and ways of thinking. Mōteatea are written to respond to particular moments, but the ways in which they are performed, through chanting, singing, lamentations, transcend the circumstances in which they were written. With this in mind, I am not surprised that Te Ao has chosen this poetically rich format as a method through which to transmit knowledge, for that is what mōteatea were made for.

It makes me think about the tired arguments around what is or isn’t Māori art, or what is or isn’t Māori knowledge, and how little weight such arguments hold when artists are creating work as rich and layered as Te Ao’s

Another lesson I have learned from Wayne (who also happens to have previously been my manager at Te Papa) is that “everything is knowledge, it just takes different forms.” We had been discussing mātauranga Māori and the way in which Western (for want of a better word) disciplines assume authority in defining culturally specific knowledge. However, when we are talking about Māori knowledge, it isn’t bound by those disciplines. He says also that “art is at the sharp end of knowledge, because it makes us think.” Te Ao’s video works in precisely this way: it is presented in a format that others can recognise, but the work itself is a sharp expression of mātauranga Māori. It makes me think about the tired arguments around what is or isn’t Māori art, or what is or isn’t Māori knowledge, and how little weight such arguments hold when artists are creating work as rich and layered as Te Ao’s.

We’re always told how whakapapa represents the ways that Māori are connected, what is not mentioned is how it reveals what we’ve lost

Asking my dad, who is from Tūhoe and Ngāti Whakaue, to help me translate the writing of a man from Te Atiawa and Taranaki Whānui felt strange, for those are the iwi my Koro was from. In translating Komene’s words, I felt the tenuous connection to Koro’s iwi ripening – these are iwi that myself and my siblings weren’t closely brought up in. Translating Komene’s words was a reminder that my connection to those iwi grew ever more distant with his death. It’s a romantic daydream, but I’d like to imagine my Koro Jim coming in from his garden and helping me wade through Komene’s words. With the death of my mother, his daughter, my own connection to home and those lands grew fuzzier still, and my romantic daydreams become desperate. Within my whānau, I can trace whakapapa to a huge number of people and iwi, the assumption being that I could absorb the richness of our histories and language through them. However, reality is that there are many voids along the way where the reo was forcibly removed from my people. This is why I ask my dad for help – we are lucky that it didn’t stop before him. We’re always told how whakapapa represents the ways that Māori are connected, what is not mentioned is how it reveals what we’ve lost.

*

Watching the two men in my life as a tunnel slowly embrace and fold around each other, my first impression is of tenderness. However, because this is a work that needs time to fully reveal itself, I went back many times, and with my most recent viewing I had a different impression: these were urgent grasps, with an insistent desperation that I hadn’t noticed before. Perhaps the two men are bound together in an unwilling embrace that neither can escape, the profound numbness of history burdening them both. Or maybe that’s my own projection, and I need to lighten up. This is another, somewhat contradictory effect that Te Ao’s work has on me: it amuses me.

The exhibition’s curator, Melanie Oliver (Pākehā), has described the work as “dynamic” for the way light and sound pull you around the room it sits within. I can’t pretend that I watched the work in any particular order, and I think it is a strength that it can be watched like this, approached at any time throughout. On one of my visits to the exhibition, I happened to enter during a particularly beautiful moment that comes when one man’s hand is laid on the other’s heart as the overlay sings “He aha te take o te aroha?” a translation of original lyrics that read, “What good is love?”

The words sung in my life as a tunnel are themselves an interesting story. They are but one of the numerous translations of the song This Bitter Earth that Te Ao has commissioned over the course of a few years. The version used in my life as a tunnel was part of an earlier work, made after he sent the lyrics from a pivotal scene in Charles Burnett’s 1977 film Killer of Sheep out to several te reo translators (Burnett’s film inspired the two earlier works in this series). One of these translations, by Paulette Tamati-Elliffe (Kāi Te Pahi, Kāi Te Ruahikihiki [Ōtākou], Te Atiawa, Ngāti Mutunga), provided the title for an exhibition curated last year by Nathan Pohio (Ngāti Wheke, Ngāi Tūāhuriri) at Te Puna o WaiwhetūChristchurch Art Gallery: tēnei ao kawa nei. In the catalogue for that exhibition, Pohio writes about the translations and their translators: “By agreeing to engage with the artist, the participants inherently represent something of their people; the subtle differences and apparent commonalities present in each body of text energise the neutral space of the gallery.”

For my life as a tunnel, the two actors, Tola Newberry (Tūhoe) and Scotty Cotter (Tainui, Fijian) were provided translations to choose from and settled on the version produced by Krissi Jerram (Pākehā). The translation, which starts with “Te pūkawa rā o te whenua,” was chosen for its lyrical nature, and Newberry and Cotter then produced a rangi for the words to be sung to. Of the many translations that have been created, I have seen three, and all three of these use a different word to represent the ‘earth’ from the original lyrics. They are ‘whenua,’ ‘ao,’ and ‘one,’ and each of these three words have multiple meanings. ‘Ao’ has been addressed, but ‘whenua’ and ‘one’ are words that also speak to deeper mātauranga.

It is this earth, and not this bitter world, that I am willing to die for

‘Whenua’ is a word that can be translated to mean both land and a placenta. Among many cultures, and definitely within te ao Māori, the whenua is buried after birth. Often, the whenua is buried within a pā harakeke specific to a whānau, effectively nourishing a plant that represents the family. ‘One’ can mean earth, mud or dirt. When Tāne Mahuta made the first woman, he made her with dirt, and her name was Hineahuone. Within Tūhoe, we have a word that represents our unity with the land. This word also serves as an iwi identifier, as a proclamation of who we are and that who we are is defined by our relationship with the land. This word is ‘matemateaone,’ and I see it as a connection to the land that is so strong you are willing to die for it. It is this earth, and not this bitter world, that I am willing to die for. In this sense, the word can represent the practice. For my whānau, this has been largely carried out by my dad, who has taken our whenua and those of our children back home to our marae to be buried.

If words can have their own whakapapa, they too are vulnerable to loss – loss of their many different meanings, and of the greater knowledge these meanings hold

Almost as if to prove Pohio’s earlier point that translators can represent their iwi through their word choice, these three translations show not only that there can be personal biases toward certain words, but that for certain iwi there are cosmological underpinnings that are not always obvious at first read. For example, I lean favourably toward translations that use ‘one’ because of my own iwi-specific understanding of land and our relationship to it. The formality within the way that these words can be read is natural: it’s a normal occurrence in te reo Māori to encounter a word that can mean a little and a lot, all at the same time. This particularity may be due to the fact that words can have their own whakapapa, too. Reo speakers often refer to ‘old’ words, words that have either fallen out of general vernacular or those that represent tikanga that is no longer practiced. If words can have their own whakapapa, they too are vulnerable to loss – loss of their many different meanings, and of the greater knowledge these meanings hold.

In his recent Auckland Writers Festival talk, acclaimed author Witi Ihimaera (Te Aitanga-a-Māhaki, Tūhoe, Te Whānau-a-Apanui) referred to himself as a “story singer.” When asked for clarification by the chair, Paula Morris (Ngāti Wai, Ngāti Whātua), he said, “Out of the Pacific…out of what was known as the singing word, because they used to call Māori the singing word, and out of waiata and chants and haka…comes a more musical approach to literature.” This is what I see in Te Ao’s work: stories woven with the richness of language, delivered through the lyrical nature of song, produced with the depth of history that connects us to the traditions of cultures and peoples who have been doing this since we were living in Te Pō.

This staging of my life as a tunnel was wholly enveloping. It forced me to think about whakapapa, reo and loss – things that are closely associated with one another but that I don’t necessarily want to deal with in a gallery. As I was drawn around the room by the work, this swirl, the physical and metaphorical taiāwhio of time, was made tangible. The grief of losing a loved one, the heartache in broken relationships, the desperation for equilibrium – these feelings are cavernous, and Shannon has created a work that allows you to sit with them, to sit with pain.

Shannon Te Ao

my life as a tunnel

The Dowse Art Museum

21 April – 22 July 2018

This piece is presented as part of a partnership with The Dowse Art Museum, which covers the costs of paying our writers while we retain all editorial control.