Finding Songs For Parents: The Good, The Bad and the Sappy

Why aren't there more songs about the experience of parenting? Gareth Shute scours the earth.

Since becoming a parent I’ve been surprised at how my ability to connect with certain works of art has changed. Movies and television shows where a child is put in danger suddenly have a firmer grip on my interest, despite the unease they give me. I find myself drawn to miserabilist fathers in literature. I take succour from reading Knausgaard’s bitter description of taking his kids to a storytime session in A Man In Love, or the equally put-upon fictional dads in Martin Amis’s The Information or the later books of Edward St Aubyn’s Patrick Melrose series (a heroin addict father makes my own parenting foibles seem very minor). In short, these media provide a wealth of relatable material for the new dad.

Yet if you know anything about me at all, then you’ll know that music is the closest artform to my own heart (having written four books on the subject and played in countless bands). Yet as novels and films take on new meaning to me, I’ve failed to get anywhere near the same sense of recognition from the music I’ve discovered since becoming a parent.

It’s as if popular music has thrown up its hands in resignation: “I kept you company at all those bars and parties; I held your hand when your partner left you; and I helped you feel joy of falling in love again. Now you’re all settled down, my job is done.”

At this point, you’re just meant to switch on something that sounds like the songs of your youth (literal dad rock) and be done with the top forty forever. Originally the term “dad rock” was used to referred to classic rock like Steely Dan and The Eagles (my own father certainly played plenty of the latter after his divorce), but these days I suppose it means Radiohead, Wilco, and Pavement (with a few spins of De La Soul thrown in for good measure).

That said, you won’t actually hear much mention of being a parent in the lyrics, even if “Magnetized” by Wilco is supposedly about Jeff Tweedy’s ties to his family, while Radiohead’s “Sail to the Moon” was written for Yorke’s son, Noah (including the fanciful idea that “maybe you’ll be president”). The trouble is that these songs are so entirely oblique – is being a parent too embarrassing to mention clearly in a rock song?

Instead, the radio frequencies and bandwidth are filled up with ever-growing numbers of romantic love songs. Perhaps it’s just that the pop music is uniquely suited to representing that first blush of infatuation that washes over a person in the first hours, days, and (if they're lucky) weeks that they spend with a new person that they're attracted to. They’ve become the modern form of a sonnet – a short outpouring of emotion that captures the feeling of love/desire while it’s still at its most electric, without qualifying or over-analysing it.

Yet if it’s the intensity of feeling that is the key to inspiring the love song, then why aren’t more songs inspired by the equally heart-grasping emotions that a child generates in their parent? The parent feels the same level of uncontrollable adoration, which bonds them to their offspring from the first moment. If you dig around the internet, you can unearth a few songs about parental love from within popular music, but most of them are simply awful – insipid versions of romantic love songs with all the raciness of sex and danger of heartbreak removed (more on which later). Sadder still is the fact that many of these songs were written by artists who gained their reputation for being groundbreaking – thus feeding into the impression that that a partner and child are somehow a ball and chain to creativity.

Despite that, I thought it’d be interesting to trawl through the songs for parents that I could find to see if I could find a few decent tracks amongst those that do exist and perhaps uncover why they are so bad on the whole.

The first, most obvious point to make is that it’s not really surprising if young pop stars and rock musicians don't have parenthood at the forefront of their mind. The problem is that even musicians who go on to long careers usually don't bother to change track. This brings up the first hurdle for the parental-love-song - the fact that popular music itself is stuck in adolescence.

Popular Music Is A Teenage Art-form

The dearth of popular songs about parenting is certainly due in part to the fact that writing pop songs is a young person's game. It has been from the start, when pop music first became accessible to the public as 7" singles in the late 1950s. The people buying these songs were teenagers and so the music followed suit - early rock'n'roll was almost entirely reliant on stories of young love/lust for its lyrics. Songs might've mentioned marriage ("going to the chapel and we're gonna get married") but only as a future proposition. Two years - even six months - seemed a long way away.

The scene did change to some degree in the sixties, when the most critically adored artists were those that broke conventions rather than followed them. The biggest act of the era, The Beatles, pushed their songwriting in new directions - getting close to our current subject on the track “She’s Leaving Home”, about a runaway teenager they’d read about in the paper. Yet by the time John Lennon had a son of his own, he had broken up with the mother and was heading into a period of heavy drug use.

Instead it was Paul McCartney that visited the baby and wrote “Hey Jude” in response - a song of advice for young Julian Lennon (though it also could be read as a song of best wishes, making it similar to Bob Dylan’s beautiful if broad ode to his son, “Forever Young”). The great thing about writing about someone else's kid is that you aren't tied down by reality - if you think "Jude" sounds better than "Jules" then you just change it, because it's not your kid/partner that's going to be offended.

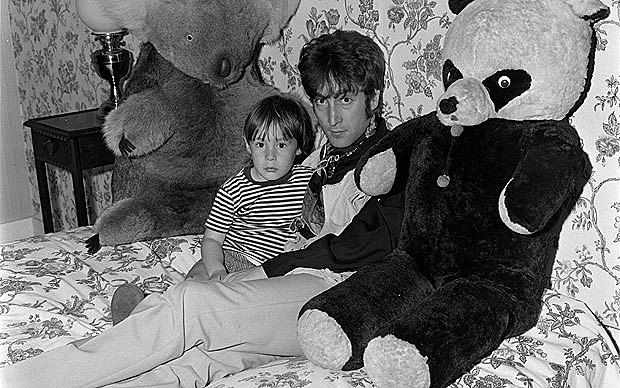

This story of Lennon - absentee parent in sight and song - is informative, because it shows the way that musicians often remain as frozen teenagers, cocooned by their fame with no need to grow up. Their managers take care of all their affairs. If they have children, then there are usually other people who can look after them. By the time their responsibilities catch up with them, most musicians have found their careers are already over. Lennon hit his own wall in the mid-seventies - drinking his way through 18 months away from Yoko (his “lost weekend”). Only on the other side of this did he become a good parent to his second kid, Sean, born in 1975. This included penning a song about him:

The lyrics sound as if they’ve been casually drawn from the songwriter’s notebook and it’s only nailed down to Lennon’s own life in the outro, when he wishes Sean goodnight. That said, it’s hard not to be moved by the final verse, given that we know Lennon will die only a few years after singing th lines: “I can hardly wait / to see you to come of age / but I guess we'll both / just have to be patient.”

It’s still true to say that the song lacks the grit of Lennon’s best output from the seventies and the melody has a syrupy sweetness to it (a charge usually directed towards McCartney’s solo output). This brings us to another difficulty with the parental love song...

Most Songs About Parental Love = Sentimental Claptrap.

Writing a good song about being a parent is simply a very hard thing to do. It's easy to knock out a new romantic love song, because the groundwork has been laid before by a million other songwriters - all you need to do is find your own twist on the subject and you can rely on clichéd placeholders to fill in any gaps. Not so with parenting songs, since there isn't much of a tradition to draw from. The result is that most parenting songs just mirror the most hackneyed of romantic love songs by being an ode to the child themselves.

The most recent examples that jump to mind are by Jay-Z and Beyonce who both wrote a song about their kid ("Glory" and "Blue" respectively), though their different approaches actually reflect a split within parental love songs in general. Beyonce takes the most common approach, which is to write what appears on the surface to be a regular love song and just direct it towards one’s child rather than a lover. All her pleading could just as easily be about a boyfriend: “Make it last forever. Come on baby won't you hold on to me, hold on to me.”

In fact, most pop stars who write songs for their children seem to take this approach. On a casual listen, if you didn’t know the subject of the song then you’d probably just assume they were about romantic love - also on the list are Alicia Keys ("Speechless"), Shakira ("The One Thing"), Adele (“Sweetest Devotion”) and Britney Spears (“My Baby"). It’s no surprise that none of these songs were successful singles, and most remained as cuts so deep they might as well have been buried – they sound like the most banal of ballads, filled with clichés left over from other romantic love songs (or the artists’ better work), with little effort to clarify that they’re actually about being a parent.

Sometimes the decision to turn a parental love song into a romantic love song is more callously driven by the market - Minnie Riperton wrote her hit "Loving You" about her daughter, but then decided it would sound better as a love ballad. To ensure there wasn’t any ambiguity about the change, she added the line "makin' love with you is all I wanna do."

Personally, I’d much rather hear a song that is more honest about its subject matter, though I’m not that interested in those that try to distance themselves from pop’s young chemical energy to the point that they end up being leaden hymns instead (like “Little Star” by Madonna or “Prayer For You” by Usher). After all, religious pop music (or just pop music trying to approximate a conventional religious experience) is a similarly fraught genre, also filled with over-emoting and layers of fake strings, and abstraction to the point that it’s hard to even picture the child they’re singing about:

You are a treasure to me

You are my star

You breathe new life

Into my broken heart

Never forget who you are

Little star

Never forget how to dream

Butterfly

May the angels protect you

And sadness forget you

Little star

There are also some hints of this in "Isn't She Lovely" by Stevie Wonder, but at least the lyrics are direct and the music has some life to it. (I’m a fan of the live version below, in which points across the stage after the first verse to the daughter he originally wrote the song about, Aisha Morris, one of the backing singers.)

Jay Z was also very direct in his lyrics for “Glory” - detailing Beyonce’s previous miscarriage and their resulting joy at now managing to have a child. But for the real poignancy about it, “Glory” ultimately risks alienating the listener with its specificity: “You're a child of my destiny / You're my child with the child from Destiny's Child / That's a hell of a recipe.” At that point, there’s not much universal about it.

More prosaically, this is also the case in many songs which use the child’s name in the title. At the end of the day, it just feels a bit weird listening to a song that’s less about parenthood as a state, and simply about someone else’s kid. For similar reasons, most romantic love songs either don’t name the object of affection, or instead create a fictional character to hang the song around.

There is a certain banality that runs across all these songs, whether vague or specific in their subject matter. Perhaps it is partly that these pop stars don’t have a very representative experience of parenting. No doubt many have nannies or carers aplenty to help with all the child-minding. They just get the good bits – they get to miss the kids, and often their viewpoint is too myopic to be widely accessible. Meanwhile, less successful musicians who have a more everyday experience of parenting are probably too busy to write songs - suddenly every spare moment is filled with a crying baby and dirty nappies and no time to even sleep. Do you really want to spend your spare moments hunched over a guitar or laptop, trying to wring your feelings into music?

No matter what a songwriter’s own situation, there is one aspect of having a child that is common to all - the surreal nature of suddenly having a new, weird little creature in your life. While sentimentality might be one reaction, an equally honest response might be to make a joke about it and some of the most interesting songs about parenting are actually ones that take a more light-hearted approach.

Parenting is a joke

In contrast to all this over sentimentality, there are at least a few songs which manage to poke fun at what it means to be a parent. A recent example that springs to mind is "Pram Gangs" by Will Slugger (the new project of Ryan McPhun from The Ruby Suns). After relocating to Norway with the mother of his child, he penned this sardonic track about being surrounded on the streets by gangs of other pram-pushing parents, who dash past speaking a language he doesn't understand, leaving him a dad adrift.

On another new track, McPhun pleads with his baby to "let your mother sleep, darling." It's sung with love, but still you get the sense of desperation.

Just focusing on the hard times is enough to make Ryan an outlier. But Loudon Wainwright III pushed even further against what you’re meant to say as a parent on his song "Rufus Is A Tit Man," which focuses on the jealousy of finding his son monopolizing his wife's breasts. Thirty years later, Rufus got his own back by writing about an argument that he and his father had after being asked to appear on the cover of Rolling Stone together ("Dinner At Eight"). More endearing (though still gently wry) is the song that Rufus wrote about his own daughter (whose mother is Leonard Cohen's daughter, Lorca). "Montauk" goes deeply into his desire for his daughter to visit him in Canada with his partner, Jörn Weisbrodt - "One day you will come to Montauk and see your dad trying to be evil/and see your other dad feeling lonely/Hope that you will protect him, and stay."

Though it’s often forgotten in the midst of his high-concept sci-fi operas of the 70s, David Bowie also channelled his parental affection into song. Hidden in the middle of Hunky Dory, "Kooks" was a song he wrote for his son, Duncan James. The lyrics essentially invite the young baby to join his parents in living the life of a kook (derived from ‘cuckoo’, the word for an eccentric or strange person was still pretty new at the time). Growing up around a dad that touted his bisexuality and dressed as an alien in pre-punk 1970s England, Bowie makes it clear that life would be far from ordinary for the young child: "Don't pick fights with the bullies or the cads / 'Cause I'm not much cop at punching other people's Dads / And if the homework brings you down then we'll throw it on the fire..."

Like Lennon, the song gains a certain sadness in context. Bowie would soon become both a drug addict and an absentee father, though he did finally make up for it by taking a year off after the release of Heroes (1977) and taking his six year old boy for a trip around the world. The life of a kook indeed.

The songs above have mostly been aimed at the weirdness of suddenly finding oneself as a parent. The strangeness of babies, for those songwriters inclined to get their heads round them, has also inspired a few songs. Before he’d even had a child himself, David Byrne playfully captured this aspect of parenting on “Stay Up Late” – the jerky rhythm of the track gives it a childlike energy and Byrne’s enthusiastic vocal delivery is filled with odd non-verbal utterances and talk of “little peepees, little toes”.

When Paul McCartney finally got around to writing a song about one of his own children in 2007, he took a similar approach. “222” is about his daughter, but mainly consists of an odd jazzy riff and McCartney observing with a tone of surprise: “look at it, look at it walking.” Closer to home, Kody Neilson (recording as Silicon) wrote the short, groovy track “Little Dancing Baby” to capture the joy of a parent watching the bizarre little dances that their toddlers come up with. His partner, Bic Runga, wrote her own song about being a parent (“Everything Is Beautiful and New”), but once again I’d always take quirky over tastefully oblique:

Of course, there’s another way to avoid sentimentality in writing about your kids, and that’s focusing on when things go wrong. The genre of romantic love songs includes a wide variety of break-up songs, but the darker side of parenting is another matter entirely.

The Dark Times

Some of the rarest and most fascinating songs are those that take on the feelings of guilt and sadness caused by a child's absence. The most specific ones are rare, both for artistic reasons (this takes a sort of biting honesty even the greatest songwriters don’t tend to have) and practical ones (imagine a song being tabled in the Family Court as evidence in a custody battle).

One of the more peculiar and revealing late-period songs by Depeche Mode, "Precious," expresses the fear of what will happen to the singer’s children after a divorce.

Precious and fragile things

Need special handling

My God what have we done to you

We always tried to share

The tenderest of care

Now look what we have put you through

This contrasts with the approach taken by Eminem to his being in a similar situation - his infamous song about his daughter (“Hallie’s Song”) actually descends into a tirade against his ex-wife. The juxtaposition of parental love and ex-husband hatred is horrifying, but you can’t fault the song as an honest representation of its author (or, in fact, for being unrepresentative overall).

At the softer end of the scale is "Son" by Warpaint, which Theresa Wayman wrote about leaving behind her son, Sirius, when she goes on tour.

]

The lyrics of “Son” are actually quite vague, though I don’t think that’s a bad thing in this case. In the filler kiddy songs relegated to the back of marquee pop albums, there’s not much ambiguity or intrigue. Here, the listener can get the sense of separation between a child and a parent, but interpret it in their own way.

“Standing in the garden

Guard my number from the one who says go

Standing in the garden

Guard my number from the one who says go

Leave the son alone”

A similar poetic vagueness is apparent on “For Annabelle” by Band of Horses, though the lyrics seem to suggest frontman Ben Bridwell is anxious about his faults being exposed by the imminent of birth of his first child.

“And a great bird is flying away

From our family tree; something wrong with me

I've got a secret or two

Hiding somewhere but

It won't take long

No it won't take long

Long”

Perhaps Bridwell was uncomfortable with stating his fears too clearly? This is even more likely to be the case for Robert Plant, who’s understood to have written at least two songs about the death of his son at age six in 1977. Both the Led Zeppelin song, “All My Love,” and his solo number, “I Believe,” are said to be inspired by this tragedy, though it would take an English Grad Student with a minor in Classics to decipher them in any detail: “Proud Arianne one word / my will to sustain / For me, the cloth once more to spin.”

Fair enough that Plant felt it necessary to cloak his feelings beyond recognition in figurative medieval language (his best songs are equally mythic), but it does show the challenge of writing on such a subject.

The meaning is far clearer in Eric Clapton's song about the death of his four year old son, "Tears In Heaven" (Conor Clapton fell out of a 53rd floor apartment window in March 1991). The song went on to be a surprise hit, though it was no doubt the religious aspect of the song that blunted the horror of its subject matter (it’s hard to imagine any songwriter of Clapton’s generation being able to face the details of the accident itself, to be fair). It’s not a personal favourite, but you’ve got to admire the bravery he showed in writing it.

Though it's magnitudes better, you might include "In The Morning" by Anika Moa in a similar category, since it covers her decision to have an abortion - an equally audacious subject for a pop music single, but a stunning piece of songwriting. Since then, Moa has continued to take the reconciliation of music and motherhood seriously - writing a whole album (Songs for Bubs) dedicated to the birth of her ex-partner's twins (since then, she has gone on to have another child with her current partner).

It’s also worth mentioning “Fourth of July” by Sufjan Stevens and “A Little Soul” by Jarvis Cocker, which both act as their author’s exercises/exorcisms conducted as conversations between parent and child. In fact, both songwriters have explained their aim in these songs was to capture the voice of their own parents – Stevens provides a stirring lullaby from his own dying mother in her hospital bed, while Cocker lays out a dramatised first-person account of his own father’s excuses. Both are great songs, though it’s hard to analyse them as songs for parents per se, given that they are actually songs about their own parents. In saying that, plenty of people can spend months if not years dwelling on what their own parents mean for their parenting – whether they can match it, whether they can avoid history repeating – and so songs like these provide a universal, assuring quality.

(While we’re on the subject of lullabies for parents, I can’t help mentioning “Just Sleep, Your Shame Will Keep” by Lawrence Arabia which will no doubt have a particular appeal for parents who are sick of the more generic earworm lullabies that they have been relying on to get their kids to sleep.)

Splitting the difference and highlighting that generational emotional weight, “Only One” by Kanye West (ft. Paul McCartney on keyboards) is another song that seems to be about the songwriter’s child, but is actually about their parent - West has claimed his own dead mother, Donda West, wrote the song through him. Nonetheless the charming video for the track manages to subtly capture West’s love for his daughter, North (aka “Nori” in the track’s lyrics) and is worth checking out on this count alone.

Is That Enough?

There’s still the possibility that I might actually be alone in wanting to hear songs about my experience as a parent. Certainly there's some relatively recent studies that have backed up the idea that the older you are, the less new music you listen to – whether you’ve got a kid or not. If parents are mostly listening to music from their youth because they’re time-poor and nostalgic, then of course they're going to end up listening to music made for people of a younger age.

Though you could just as easily flip the interpretation of this correlation on its head - perhaps older people return to the music of their youth, because there aren't really any songs written for people in this time of their lives. This would mean there’s a hole in the market for songs of this type and - critically and commercially - it could be a lucrative one. The older a listener is, the more likely they are to be willing to pay a decent amount for the music they consume (even at the extortionate mark-ups CDs manage to still be sold at, for example).

If you do share my interest in the subject, then I’ve put together a short playlist of songs and I’m happy to take more suggestions. The list is pretty MOR at this point, so it would be great to add some more abrasive or sardonic tracks to mix things up. As a common language, I don’t think we parents are going to take back pop music from the kids, but at least we can carve out our own tiny corner of the field.