Summer Reading: Our Picks from the Internet 2016

The best reading the internet came up with in 2016 - as chosen by writers featured in the Pantograph Punch in 2016.

The best reading the internet came up with in 2016 - as chosen by writers featured in the Pantograph Punch in 2016. (Read the best of our own 2016 articles here).

Sarah Jane Barnett (Books Editor)

“When people ask if libraries are important and relevant these days I want to scrape my fingernails down my face. Are you kidding! As the days get darker (and they are getting darker), libraries give us context; they contain our past, our present, our future, and the way we are different and the same.” - Lynn Davidson

Well worth a read and to kick this list off is Lynn Davidson’s candid revelation of the hidden truths of being a writer, woman and teacher in her amazing essay, 'A roof over my head'.

‘On Sky News last night, I realised how far some will go to ignore homophobia’; Owen Jones did a great job at calling out bigotry after the Orlando shootings.

In a similar vein Brannavan Gnanalingam's ‘Essay: why is New Zealand literature so afraid of race? And how come the Spinoff books section is just as bad?’ highlighted the subtle racism found in New Zealand literature.

But of all the articles, the one that changed my life in 2016 was Jess Zimmerman's 'Hunger Makes Me' on Hazlitt, which explores the relationship between appetite, hunger, and the space women feel comfortable taking up in the world.

The issue that has weighed most on my mind in 2016 is how to change minds, and whether the viewpoints of those who you consider to be abhorrently extreme can even be changed. In my social circles, the left generally has chosen to answer the former with "yelling at people you disagree with" and the latter with "no".

‘The White Flight of Derek Black’ by Eli Saslow, about the apostasy of a young white supremacist, posits a different argument. It’s one that's both enticing because of the degree of change achieved and daunting because of the multi-year commitment to doing so, as well as the implication that the person who wants change must leave their familiar environment to be open to it. The article's larger lessons are left in the background for the reader, though; at its heart is a human story that unfolds with acute observation and sensitivity. It hasn't left my head since reading it, and as the 2017 New Zealand election looms, I expect it to continue to resonate through the upcoming year.

Adam Goodall (Wellington Theatre Editor)

“Throughout the eight-month run of the show, actors Benson and Bigley were covered in bruises. During one performance, Cox-as-Joe slammed Bigley-as-Chris into the on-set refrigerator so hard that the refrigerator smashed into the back wall of the set and cracked it.”

‘At Profiles Theatre the drama—and abuse—is real’ by Aimee Levitt and Christopher Piatt revealed a 20 year history of mistreatment of actors and crew at the Chicago theatre. This brave investigative piece, an attempt to protect workers engaging with non-Equity companies like Profiles, was quickly followed up by this one, also written by Piatt. Piatt wrangles with his difficult feelings around missing something horrific as it happened right under his nose and praising the results of that horror. It's a critical piece of writing about the social responsibility that underpins being a critic; about how, when someone uses their art to tell you who they are, the most responsible thing you can do is listen.

In RimWorld, there are no bisexual men, only gay or straight men; there are no straight women, only gay or bisexual women.

Claudia Lo's How Rimworld's Code Defines Strict Gender Roles is a perfect example of that responsibility in action, digging deep into the code of wildly popular roguelike survival game Rimworld to find retrograde ideas about sex, gender and romance hard-coded into the game's DNA. Lo unpacks this Russian nesting doll of bi erasure and normalised harassment with clarity and force. It's very, very good.

What is the precise moment, in the life of a country, when tyranny takes hold? It rarely happens in an instant; it arrives like twilight, and, at first, the eyes adjust.

It is tempting to assume that the freedoms we take for granted in liberal democracies are an inevitable consequence of human civilisation. The truth, of course, is that our societies are curious anomalies against the vast backdrop of human conflict and suffering. A quick glance at our past or to less fortunate nations today can only confirm the fragility of our current circumstances.

The New Yorker's Evan Osnos captures the spirit of our complacency on this topic in his short review of "No Wall Too High," which describes Xu Hongci's initial flirtation with Mao Zedong's regime and his subsequent escapes (yes, plural) from a laogai prison camp. The allusions to Trump are obvious, from the title of the book to Mao's promise of "making China strong again." The essay begins by reminding us of our own susceptibility to tyranny, as well as our responsibility to stand up to it. It ends on a similar note:

Tyranny does not begin with violence; it begins with the first gesture of collaboration. Its most enduring crime is drawing decent men and women into its siege of the truth.

In the darkness of global turmoil, however, the warm glow of cricket continues to shine. Fostered by hours of deep introspection – from the contemplative stroll toward the top of a bowler's mark to the lugubrious post-dismissal pavilion-bound march – cricket writing is surely one of the great literary sub-genres. Anthony McGowan's brilliant essay, A Very English Passeggiata, adds to the tradition. With references to Galileo, Italian youth culture, and ancient Meso-Americans, the erudite homage to the amateur game is filled with magical lines like the following:

I can generally manage to slap it away, somewhere between cover and backward point, my bat at the sort of drooping, melancholy angle that in a porn movie would call upon the urgent attentions of the fluffer. Imagine the weatherman pointing in a desultory fashion towards a squall in Kent.

Lana Lopesi (Visual Arts co-editor)

This essay by Zoe Todd (which I admit was not published in 2016) is one of the only pieces I read at the beginning of 2016 which I am still obsessed with now. In it Todd calls out the relentless cherry picking of indigenous epistemology that goes unacknowledged. One of my favourite parts is:

So, again, I was just another inconvenient Indigenous body in a room full of people excited to hear a white guy talk around themes shared in Indigenous thought without giving Indigenous people credit. Doesn’t this feel familiar, I thought.

My pick for 2016 – it’s not an article but Jill Soloway's Masterclass speech at the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF), described thusly: “In this keynote address, Jill Soloway takes on the critical feminist concept of the female gaze and asks what it would take to bring it the forefront of film, art, and culture. By making space for women to take the lead in shaping female protagonism, can we get one step closer to igniting a revolution to overthrow the patriarchy?”

Janet McAllister (Editor-in-Chief)

“I will come forward” - The Spinoff's piece about Andrew Tidball – was courageous, important and influential reporting.

For sheer absurdity, I recommend Gay Talese’s problematic, riveting piece The Voyeur’s Motel – published in The New Yorker to promote Talese’s book of the same name. It reads too weird to be true, and whaddaya know, it was followed by several chas(en)ers, such as this one at Salon, calling into question Talese’s fact-checking and his ethics. Yep, if somebody says they witnessed a murder, even several years previously, you should probably do something about it. Even if the victim was a woman.

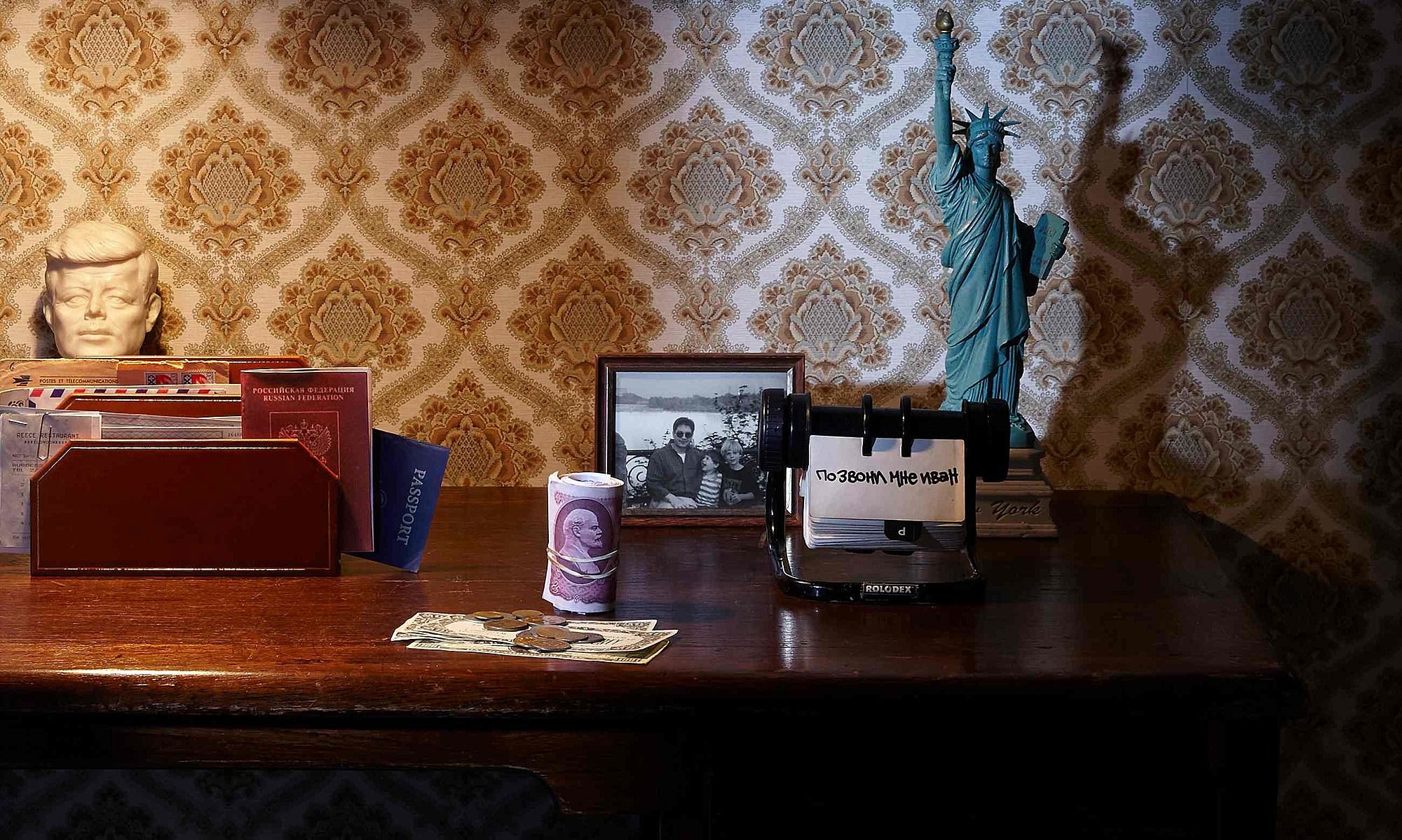

Talking of spying, ‘The Day We Discovered Our Parents Were Russian Spies’, by Shaun Walker, delivers on the promise of its title.

Although it was her Tarzan review that garnered her fame, and her piece on Idris Elba was problematic, it was Emily Writes’ Ghostbusters review that was a revelation to me: “big girls like me, having wine at 11am, get to relax into a movie that doesn't once drop a casual rape joke or belittle women as a group. Ghostbusters 2016 is basically women releasing the tension in their shoulders: The Movie.” Humour as a weapon against bullies; I’m in.

Joe Nunweek (Senior Editor)

In a year of "the state of things" that ended in orthodox, trite and self-serving post-mortem of finger-pointing and reassurance (I'm looking at Mark Lilla's dreadful 'The End Of Identity Liberalism' here, but you can exchange it with a half-dozen others) Eleanor Robertson's 'Get Mad And Get Even' was a piece of writing I kept coming back to and coming back to find some sort of compass. Some wound-licking liberals would have you believe that Trump, Brexit and beyond are the result of some sort of browbeating and alienating inculcation of basic feminism into policy and campaigning. Robertson, on the other hand, firmly presses home that liberals are the ones that have done a great deal to trash and commodify feminism's transformative and revolutionary potential in the first place, and that we're all the poorer for it. Cling to it as everything from Twitter to the NZLP flails in the wind in the coming weeks and months.

From Stir Journal, an American-based online publication that seems regrettably sparse in its updates, two devastating pieces that aren't oppositional but poised as perfect counterweights to symbolise the year. Hope Wakube's "My Father Could Have Been Killed By Police" tells the multi-generational story of a refugee family who came to 1970s America expecting missionary-style welcomes and finding only alienation and hate; Jonna Ivin's "I Know Why Poor Whites Chant Trump, Trump, Trump" charts a family tree of hurt, resentment and humiliation starting with the first indentured servants who walked into the Appalachians in the 1600s and eked out a subsistence and waited for a saviour, or at least someone to blame.

Lastly, not from 2016: but awfully prescient. This is the year I and I think plenty of others discovered Carmen Hermosillo (aka humdog)'s 1994 piece Pandora's Box. The primitive forums of the 1990s she describes (social clusters in cyberspace, the taboo archived topic of News 1290) are so outdated as to be kind of cyberpunk; her suspicions and fears about how virtual social space is constituted, and for whose benefit could have been written today:

...proponents of so–called cyber–communities rarely emphasize the economic, business–mind nature of the community: many cyber–communities are businesses that rely upon the commodification of human interaction. they market their businesses by appeal to hysterical identification and fetishism no more or less than the corporations that brought us the two hundred dollar athletic shoe. proponents of cyber– community do not often mention that these conferencing systems are rarely culturally or ethnically diverse, although they are quick to embrace the idea of cultural and ethnic diversity. they rarely address the whitebread demographics of cyberspace except when these demographics conflict with the upward–mobility concerns of white, middle class females under the rubric of orthodox academic Feminism.

At some point after June 23, after the UK voted leave in its EU Membership Referendum (aka Brexit), and after David Cameron resigned, the pound was tailspinning and everything was lining up for some kind of catastrophic, Brexit-fueled implosion, it struck me that Zadie Smith would know what to make of all this. A month and a bit later, ‘Fences: A Brexit Diary’ appeared.

In the essay, Smith takes the reader through her own hours and days leading up to and following Brexit. She writes about the initial outrage and shock she felt, the blame she leveled at stupid and ignorant leave voters. But she also pauses and takes a long look at herself, and, by extension, everyone else in the same middle-class bubble. Like her novels, the essay isn’t straightforward. Smith asks messy questions, follows threads and more than once throws up her hands in despair. Fences, an emblem of a fractured society, crop up all around. After rereading it (I’ve reread it a lot in the past few months), it feels very attuned to the kind of year it’s been. Maybe uncertainty is not such a bad state to be in.

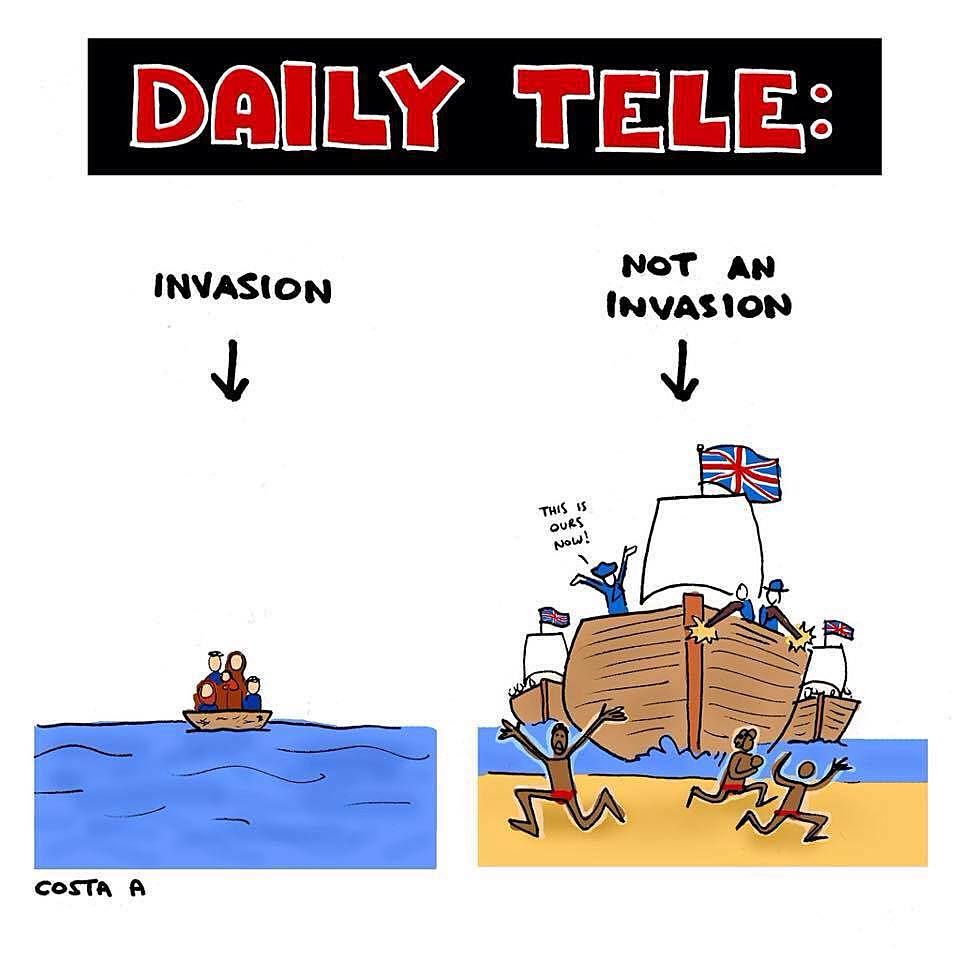

I found this article powerful – ‘Haalitosis’ by Tina Ngata on The Non-Plastic Maori:

…how is it, that while others are finally coming to terms with the injustice of celebrating colonial acts of violence, New Zealand, who purports to be the progressive nation of harmonious race relations – is about to invest many, MANY millions into a celebration of Cook’s arrival, a celebration that will last not just for a day but for an entire YEAR (Atua give me strength) – and labeling it the “inception” of our nation?

And cartoonist Toby Morris has done some excellent Pencilsword work - my favourites from this year are ‘Rent Rage’ (“25% of Aucklanders aged 20-24 share a room with a non-partner”) and ‘Holes’ (“What else as a country, are we blanking out?”).

Rosabel Tan (Director)

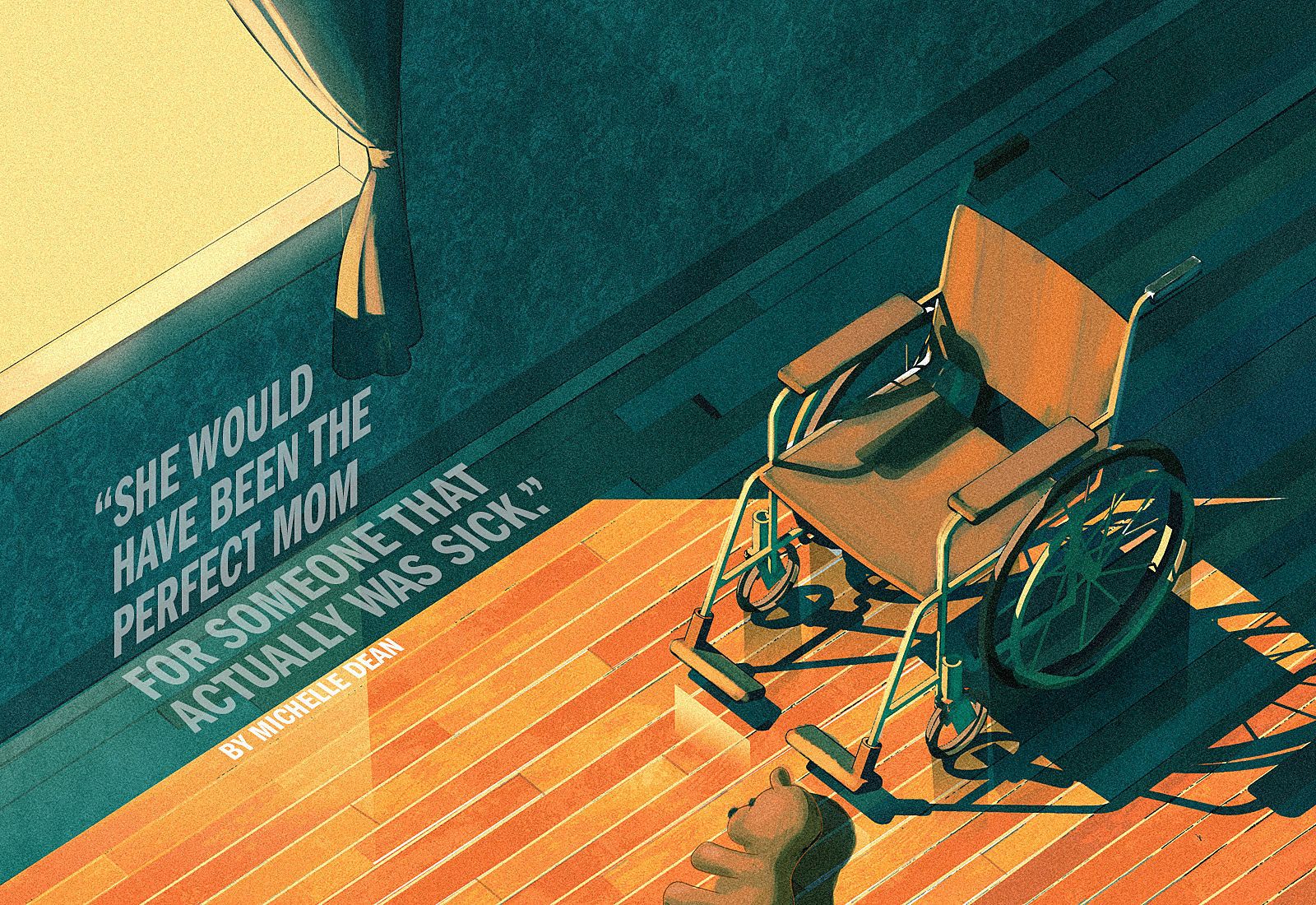

It was a perfect story for a human interest segment on the evening news: a family living through tragedy and disaster, managing to build a life for themselves in spite of so many obstacles. But the story wasn’t over. One day last June, Dee Dee’s Facebook account posted an update.

“That bitch is dead,” it read.

Gypsy Blancharde's friends and neighbours believed that she was devastatingly sick and that her mother, Dee Dee Blancharde, had devoted her life to caring for her. Nobody suspected otherwise, least of all that Dee Dee was forcing her daughter to take medication she didn't need and to undergo unnecessary medical procedures. Michelle Dean's searing piece on Buzzfeed takes us through their life together, and the circumstances that led to Dee Dee's murder in 2015.

And that is an image that will stick with you, let me tell you: Justin Bieber, on his knees in Tyson Chandler’s bathtub, wet and sobbing against Pastor Carl’s chest, so unable to cope with being himself that he has to be born anew, he has to be declared someone entirely different, in order to make it through the night.

Earlier in the year, Taffy Brodesser-Akner took a deep and curious look at the cult status surrounding Hillsong Church and the two dudes who brought it to America, Pastors Carl and Joel. It's simultaneously sceptical and open-minded, and unexpectedly moving in what it unravels. Read What Would Cool Jesus Do? here.