Three Characters in Search of an Author: Te Pō and the Legacy of Bruce Mason

Bruce Mason has been missing from our stages for quite some time, so why is he popping up now in Te Pō?

Bruce Mason has been missing from our stages for quite some time, so why is he popping up now in Te Pō?

You might wonder what playwright Bruce Mason would make of the current state of theatre in New Zealand, nearly 35 years after his death. No doubt he’d approve of the emergence of indigenous companies like Taki Rua and Tawata Productions. He would be gladdened by the variety of local drama across the nation’s stages, but infuriated that it is still almost impossible to make a decent living as a playwright in this country. The discovery of the Bruce Mason Centre located in the Te Parenga (aka Takapuna) of his childhood would satisfy his immense ego.

He might also be amused, or perhaps bemused, to find himself as a narrative device in Carl Bland’s Te Pō, alongside his characters Detective Inspector Brett and Werihe Paku (from Awatea, 1965) and Reverend Athol Sedgwick (The Pohutakawa Tree, 1955), living out an afterlife beyond the confines of their original texts.

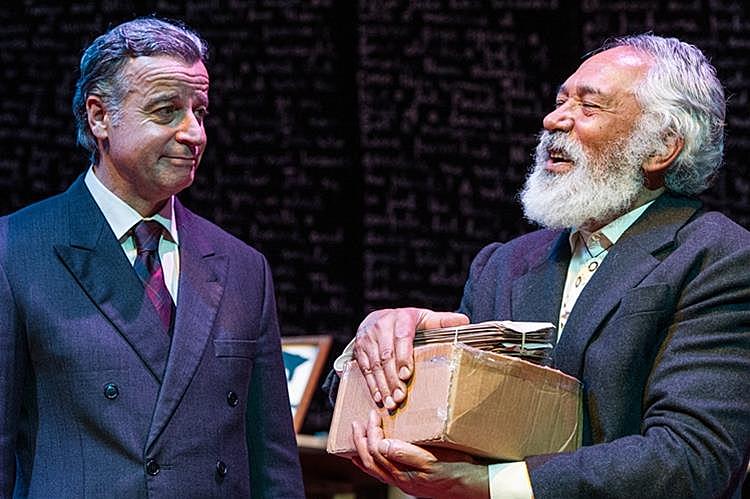

In Te Pō, Bruce Mason is missing. Inspector Brett (Andrew Grainger) is on the case. Werihe (George Henare) patiently waits for him to return – he says he has an appointment with the playwright. The reverend Sedgwick (Carl Bland) was possibly the last person to talk to Mason before his disappearance. Sedgwick is a man of faith who has lost his own following the death of his wife. Werihe is a blind man, also a widower, with piercing insight. Brett is a fictional character searching for facts.

The fact is, Bruce Mason has been missing from our stages for quite some time.

The fact is, Bruce Mason has been missing from our stages for quite some time. If Mason was to make his second coming now, he might indignantly cry, in clipped tones: why are you still not putting on my plays? Auckland Theatre Company led a recent resurgence with its revivals of The Pohutakawa Tree (2009), The End of the Golden Weather (2011), and Awatea (2013), but it was a pocket of activity that did not spread across the country. And then there are all the others that we don’t hear about very often, from Birds in the Wilderness (1958) to Blood of the Lamb (1980), his final play. What makes Te Pō such an oddity is the choice to feature characters that general audiences will only dimly be aware of, if at all. New Zealand theatre does not celebrate its past. A Unitec acting student can go through their training without exposure to Mason. At the University of Auckland, Awatea has held out for years on the Stage Two/Three New Zealand Literature course. Golden Weather used to be taught on the stage one syllabus, but now the the general drama undergrad otherwise misses out.

It’s no mystery that Mason is missing - we’ve known for some time. Even in his own lifetime, there was a sense that he hadn’t been given his due. The real mystery is why has Mason popped up now in Te Pō?

*

Detective Inspector Brett assumes that everything he sees and hears is fictional. He searches for the “humble little brick of truth” from which he can build a case. Choose the wrong brick, and the whole case will collapse. A brick sits upright on Bruce Mason’s writing desk. It was given to him by Sedgwick, a souvenir from Berlin after the war. This brick marks the end of the writing process, when a story is complete, it is turned upright, just as it was used in Berlin to mark a completed pile of bricks during the rebuild. From the ruins of an old culture a new one can occur. For Brett, the brick symbolises truth; for Sedgwick, it represents transformation.

Mason himself offers a similar metaphor in a Kaleidoscope documentary recorded shortly before his death in 1982 (you can watch it for yourself at NZ On Screen). Mason looks for a moa bone – if you can find that, then with imagination, you have enough to create the whole bird. In his writing, Mason was often inspired by newspaper articles and true experiences that he could transform into fiction. For Awatea, Mason drew on incidences he had heard about: a young Māori who was the first to achieve university entrance in his district, but dropped out of medicine and never showed his face at home again, and a marriage where it emerged the groom was not a doctor as claimed, but a housepainter. “The two stories fused in my mind,” wrote Mason.

Carl Bland’s first brick, or moa bone, came during his performance in ATC’s Awatea, in which he played Brett (Andrew Grainger played the other police officer, Jameson, in this production). While Bland was sitting in his dressing room, ATC Artistic Director Colin McColl walked past and said, “You look just like Bruce, you should do a one man show about Bruce Mason.” Recalling this, Bland jokes that “I don’t look anything like Bruce… Colin’s eyes must be going or something,” but the suggestion worked away in Bland’s mind.

Bland had been reading about Mason as part of his research for his role in Awatea, and he had found the Kaleidoscope documentary moving: “He was at the end of his life, he’d been at the coal face.” There are two interviews with him. In the first, he’s in shadow, a figure sunken in his chair. In the second, he’s lit close-up, and we can see the effects of his jaw cancer. His face is sunken on one side, and he looks like an emaciated Goofy. He’s full of fervour though, and displays his supreme command of language.

Bland kept wondering about Mason. How he would work from fact and turn it into fiction, the opposite of what Bland would normally do, whose previous work includes 360 and Head. Te Pō is the first play he has written without his wife, Peta Rutter, who died in 2010 of a brain tumour. Bland wasn’t sure he could do it, “But somehow it happened.” He wrote the play in three weeks, and it “came out in a really clean way.” The text has barely changed since then. There was a Next Stage workshop at Auckland Theatre Company last year, where a reference to the ‘Golden Kiwi’ lottery was the only addition. Bland puts it down to the emotion he was feeling at the time, which he was able to channel into a really clear idea. Te Pō wrestles with memory, purpose, life, and where we go when we die – only the really big themes of our existence.

*

The air in the theatre changes on the opening night of the Auckland season when an old crackling audio recording of The End of the Golden Weather is played. This was made with some difficulty by Mason himself, who had to hold half his face up in order to deliver his text. The ghost of Bruce Mason invites us to “voyage into that territory of the heart that we call childhood.” He’s a man out of time, his dry not-quite-British-but-not-quite-Kiwi tones has me picturing the criminologist from the Rocky Horror Picture Show.

Director Ben Crowder hadn’t heard Mason’s voice before using it in the show. For him, it “feels very purple.” Crowder had some awareness of Mason from university, and owned an omnibus edition of his plays that he hadn’t looked at very often. Golden Weather has a mythical standing, even if you haven’t seen or read it, but for Crowder, Mason was very much a figure from history. I suspect this is how many contemporary theatre makers feel. Mason is from the past, a pioneer, but with little bearing on how we make theatre now.

*

I performed on the Bruce Mason Centre stage, aged 10, in a production of Oliver!, well before I knew who Bruce Mason was. It wasn’t until I saw Stephen Lovatt’s streamlined version of Golden Weather at age 17 that I realised that New Zealand theatre was hiding such a gifted local writer. This version of the play has remained one of my warmest theatre memories, and I often think back on Lovatt’s proud and vulnerable Firpo, and his plea for acceptance. I saw the film, read the plays and reviewed the ATC shows. Mason has been a constant presence in my postgraduate studies. For my Masters I sought to reclaim landmark plays from New Zealand’s past from 1948-1970. Not only was Mason writing throughout, but he was also there to pass judgment on everyone else trying to create New Zealand theatre. My ongoing PhD thesis focuses on New Zealand theatre performed internationally, and I’m looking at Mason’s tour of Golden Weather to the Edinburgh Fringe in 1963, which is really where it all begins. My research led me to the Bruce Mason archives at at the J.C. Beaglehole Room at Victoria University, and I got to handle with care cartons of ephemera and scrapbooks. I was thrilled to find his cue script for Golden Weather, lines and words from the printed text bracketed out by hand to indicate the cuts for the acting version.

I’m fascinated with how completely Mason dominated his period in New Zealand theatre history, and yet there is a sense that due to hostile conditions, such as a general preference for overseas plays, he was unable to achieve his potential. He’s our Miller and our Ibsen and our Chekhov, but the way we’ve treated him, you wouldn’t know it.

With The Plays of Bruce Mason: A Survey, published late last year, theatre critic John Smythe’s overall mission was to commend to theatre companies the desirability of reviving Mason’s canon. He compellingly advocates that New Zealand audiences “should all be familiar” with Mason’s various plays. Smythe believes The Pohutakawa Tree is particularly significant not just for local drama, but global drama too, “as worthy a cultural artefact” as any of the major works.

He’s our Miller and our Ibsen and our Chekhov, but the way we’ve treated him, you wouldn’t know it.

Smythe summarises Mason’s career as a “triumph of the imagination over the obstacles of our limited self-awareness, low self-esteem and rampant cultural cringe.” Mason had to battle a society hostile to artists seeking to create a local theatre. As a character remarks in his early play The Evening Paper, “We’re not critical people… we know nothing of art or culture. There’s no history to talk about”.

In the Kaleidoscope documentary, Mason repeats the widely-held idea that the culture came from elsewhere. Mason reveals that his children used to be ashamed of his profession. When quizzed by school mates, they’d say their Dad was a doctor and their Mother was the writer. The interviewer asks Mason if it has got easier. His brow furrows, there’s a grimace, and a sigh, and his eyes shoot to the left. Mason thought that the majority of New Zealanders thought his work was ludicrous, pretentious, and pointless. One of Brett’s early theories in Te Pō is that Mason may have drowned himself at Te Parenga: being a playwright would explain the despair and desperation that would make a man walk into the sea.

Smythe’s survey concludes with a vision of a “playwrights’ theatre” to produce new and classic home-grown theatre, so Mason would be neglected no more. But really, Mason is the lucky one. Smythe’s book perpetuates the idea that Mason is the only writer of value to come out of the New Zealand theatre dark-ages of the 1950s and 60s. As Roger Hall wrote in his review, entitled “Skimming the works of a master”, the book “gives the impression Mason had no fellow playwrights.” Hall lists Peter Bland, Warren Dibble, James K Baxter, Owen Leeming, Mervyn Thompson, Alistair Campbell and Joe Musaphia for consideration. I’d also add Stella Jones, Allen Curnow, and Claude Evans, and companies Red Mole, Amamus and Theatre Action. Ironically, Mason once called out Roger Hall’s claim that Glide Time (1976) was the first time a New Zealand audience could truly recognise themselves on stage, saying Hall “did not spring on us, without visible forebears, like Athene from the skull of Zeus”.

You can trace a direct line with New Zealand’s obsession for solo plays back to Mason... Mason’s plays are too epic, the cast list too large, the values too out-dated.

Speaking of forebears, you can trace a direct line with New Zealand’s obsession for solo plays back to Mason, but essentially our theatre has entirely moved on from then. Mason’s plays are too epic, the cast list too large, the values too out-dated. Theatre in New Zealand has shifted. The brick of truth is that for many practitioners working today, he’s entirely irrelevant.

*

Te Pō is nothing like a Bruce Mason play. There’s a three-act structure, sure, but it borrows heavily from farce, and director Ben Crowder sprinkles whimsy and magical realism all over it. Crowder likes that “a lot of what is written isn’t very possible to put on.” The set of Mason’s study, designed with superb attention to detail by Andrew Foster, is full of surprises. Chairs move on their own whim. A piano plays typewriter taps instead of chords. The characters have no concept of a fourth wall, and are compelled to share their thoughts, often stepping outside the stage frame. There are animals, too: a seagull, a big fish, and something else quite unexpected, designed by Main Reactor and operated by Ella Becroft. It is difficult intellectually to explain what’s going on with these creatures in the play, but they certainly connect on a purer emotional level. Bland sees them as witnesses “to these stupid humans around them… they are like God, just watching, wondering.”

Then there are songs performed Prince Tui Teka style by George Henare, full of fervour and hip swagger. “I can’t stop loving you,” he belts. Like the animals, you wouldn’t normally connect these elements with this type of story. But the songs are all about love, and lost love, which pull us in a roundabout way into Te Pō’s world.

I asked Bland, why these three figures from Mason’s works? Having played the character in Awatea, Brett was close to Bland’s heart, and he had latched onto the idea of a detective story early on. Werihe also transferred from Awatea. Sedgwick came over from The Pohutakawa Tree; Bland thought his experiences in WWII made for an interesting character. It’s a strong combination. When they learn about their fictionality, Brett and Sedgwick regret that they were never in a play together.

You don’t need to know the plays they come from to appreciate the characters in this story. Crowder thinks that prior knowledge is only useful to a certain point, after which it should be parked. In John Smythe’s review of the Wellington season, he acknowledges that “too much learning could be a disadvantage, in that those who know Awatea well will realise Bland has taken a large slice of artistic licence in deciding Werihe and 12 year-old Bruce chatted on a daily basis that summer at Takapuna Beach (aka Te Parenga)”. Crowder likens it to when his father, who was at sea all his life, watches a film and grumbles at shipping inaccuracies. He hopes no-one will hold on too tightly, that they will let go where they need to, and fall into the show. As a Bruce Mason nerd, one of the most niches of niches, there is an awful lot that I get out of this play. It is useful to have some background knowledge, mostly to gain insight around the particular choices that Bland makes in his script.

*

Grief was an uninvited visitor when I went to see a run of Te Pō in the huge rehearsal warehouse at Corban’s Estate. It was the day we learnt of actor Sophia Hawthorne’s passing, the news was raw, and the cast wanted to talk about how the deaths of loved ones had impacted their own lives.

Henare has a philosophy of death aligned with Werihe, the wisdom that years of experience grant you. When his mother passed away many years ago, Henare says he was a mess. It was then that he realised what the three days of mourning was all about: “You talk about things, you get it all off your chest, you laugh, you cry. By the third day I thought, there is a little bit of grief there, there’s sadness, but it’s gone, I’m cleared”. Then his father went, a brother, another brother, his sister, “and then it just gets easier”. Recently he had lost a nephew, and it didn’t hit as hard as it used to. “You just start accepting that they’ve been here, done their thing, their lives have moved on. It’s sad, but they’ve gone on… the tides come in, the tides go out”.

Andrew Grainger’s father had passed the week before. It changed the way Grainger felt about the play. “A lot of the ideas make more sense in ways and make less sense in other ways,”

You start forgetting the person, which is very disturbing, and you wonder, did that happen?

Sedgwick’s story has similarities with Bland’s story, and his feelings around grief and Peta’s death. Bland finds it distressing that sometimes when you think back, you start wondering if your old life was real. “You start forgetting the person, which is very disturbing, and you wonder, did that happen?”

Te Pō ends with a sermon from Sedgwick, which is actually a story written by Peta just a few months before she died. Sedgwick begins by telling us the Virgin Mary was actually fat, and didn’t like blue, and gives us the ‘real’ nativity story. It questions God, and life, and how much of what we think we know is fact versus fiction. “That’s where it all boils down to in the end”, says Bland, “that thing about looking for truth, it always goes to the big question of God in the end”. The sermon is silly, and clever, humorous, and stunningly true. There’s an ache in my heart. I’m tearing up. I try to hold onto this feeling, this light, as long as possible after the curtain call has finished and I’ve left the characters in the theatre behind.

*

“What happens to birds at night?” wonders Werihe at the start of the play. We might also ask, what happens to the characters in a play when the script is shut? Or when their author dies? The style of Andrew Foster’s set and Elizabeth Whiting’s vivid costume design is suggestive of the early 80s. My personal reading is that the existential crisis has been set in motion by Mason’s death, timed perfectly to mark the end of an epoch on 31st December 1982.

In Luigi Pirandello’s influential absurdist work Six Characters in Search of an Author (1921), a family of characters interrupt a rehearsal and demand the company of actors tell their story. Pirandello gives the note that the characters “should not appear as unreal beings, but rather as created reality, immutable constructs of the imagination, and therefore more real and substantial than the naturally changeable actors.” The Father character says they are “more alive than the kind of people who breathe and wear clothes! Not as real, perhaps, but more true.” One of the many ideas in Te Pō is that anything that produces difference in the world is a being. A brick. A Play. A character. All as real as us. Fictional characters have an incredible influence over our perceptions of the world. We spend an awful lot of our lives analysing fictional characters over people who have really lived – we are never assigned autobiographies to read at school.

Unlike Six Characters, our three characters in search of an author in Te Pō do not immediately recognise they are fictional. Pay attention though, and you can count up the many metatheatrical nods in Bland’s script. Brett has lately begun to doubt himself. Sedgwick finds himself somewhere between Being and not being. An action is described as “completely out of character.”

Smythe has noted the similarities with Beckett’s Waiting for Godot and Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are dead. I’m reminded also of A Play: A Play by John Kneubuhl (published posthumously in 1997). The grief in that play is about the loss of Hawaiian identity. Half-way through, the characters begin to realise that “everything we’ve said – done – as ourselves, actors, as characters in this play – everything – is all written down up to this point.” In Te Pō, Brett pulls Awatea from Mason’s bookshelf and feeds Werihe a cue, which he responds to instinctively. In A Play: A Play, one character states that “You’re… you’re just characters in a play, saying speeches someone wrote for you… But I’m not in the play…. Nobody wrote me… I’m not in a play, I’m not in a play, I’m not in a play.” This echoes in Brett’s character, who also refuses to accept he’s a fiction. Sedgwick is comforted however. If he is fictional, that means he can choose his future and change his past. However, that only works if someone else isn’t already writing his story.

There’s a tender sense that through Te Pō, Bland is working himself out too, acknowledging his grief through art, so he can move on in his own way.

In A Play: A Play the characters make peace with their fictionality with the thought that the playwright is working himself out: “To find himself. Create himself. and in that work, he needs us. He becomes himself, through us… He needs us, desperately. I take comfort in that”. There’s a tender sense that through Te Pō, Bland is working himself out too, acknowledging his grief through art, so he can move on in his own way. He needs them. And we need them too, to help articulate our own feelings, our own losses along the river of life.

The characters tell us that “just because I was imagined doesn’t mean I wasn’t real.” Mason talked about the redeeming truth of imagination. In A Play: A Play we understand the characters’ stories will continue to repeat on a cyclical loop. But in Te Pō they will return to the darkness, until they are needed again. They fear they won’t be: “How do I know if I’ll be imagined again?”

If the Six Characters met our three characters, they would advise them that they have nothing to worry about. The Father says:

If you’re lucky enough to be born alive as a character, well, you’ve nothing to fear from death. You can’t ever die. The man will die, the author, the instrument of creation, yes, but the creation itself never dies! And in order to live forever, it needn’t have any extraordinary gifts, or the ability to work miracles. I mean, who was Sancho Panza? Who was Don Quixote? They’ll live forever, even so, because their seeds, as it were, had the good fortune to fall on fertile ground – an imagination that knew how to grow and nourish them, and make them live for all eternity!

Mason certainly knew how to grow and nourish his characters (and in a rather unforgiving local climate), but perhaps it’s at the point where your characters are adopted by another writer that eternity really is assured.

We don’t know our history. Its symptomatic of the short-term visions of the industry, where too often, plays are only on for one short season before disappearing forever into Te Kore, the void, their characters never having the opportunity to be imagined again.

Te Pō acknowledges that we have classics in New Zealand drama – something we don’t do enough. And it also shows that we have enough distance from our classics that we can do different things with them. A new theatrical experiment is exactly the right way to honour and remember Mason.

This play would not have existed in this form without ATC’s revival of Awatea. We need to acknowledge our theatre history, and keep it alive through productions and discussion, though we should not do this uncritically. We should not revive a play just because it is by Mason. Revivals should always be justified based on the light they can shine on our contemporary situation. We should look also for those hidden behind Mason’s long shadow, as well as those who came after. We need to rescue more characters from te pō and bring them to te awatea. And we need more new work with a strength of vision equal to Te Pō’s.

Masterpiece is not a word that’s used all that often to label New Zealand plays (a residue of an inferiority complex?), but Metro’s Simon Wilson is right: Te Pō is a masterpiece, just as The Pohutakawa Tree was, and is. Te Pō borrows from and pays tributes to its forebears, but uses this moa bone to stand alone.

Te Pō is at the Auckland Arts Festival

9 - 14 March