The Humanity of Both

Do you need to walk in someone else's shoes to appreciate how hard their road is? Philip McKibben argues that dismantling privilege needs to be based in understanding if it's going to work.

Do you need to walk in someone else’s shoes to appreciate how hard their road is? Philip McKibbin argues that dismantling privilege needs to be based in understanding if it’s going to work.

Not long ago, I was scrolling through my Facebook feed when I came across this:

No matter how sensitive you are

if you are white

you are

No matter how sensitive you are

if you are a man

you are

The words were from a poem, ‘Those tears’ by Chrystos.

The suggestion was that if you’re white, or a man – or both – you cannot, and will not, understand those who are not. The poet’s point was, in fact, more subtle: no matter how willing you are to see beyond your privilege, to appreciate its causes and consequences, the fact of your privilege remains. She suggests the mere fact of your privilege can be oppressive in itself, whether or not you recognise it.

I’m a white man (among other things) and Chrystos’ words struck me. Although I’m privileged, and despite my flaws, I care deeply about our world and the people who share it with me. I found those words unsettling when I read them. Not because they pointed at my privilege, but because they represented it to me as an insurmountable barrier – the sort that Donald Trump would build – rather than something that, working together, we might deconstruct.

Privilege – white privilege, male privilege, privilege in all its forms – is a real thing, with real consequences. It’s the unmerited advantage people enjoy through their association with a particular group, and it always entails corresponding disadvantage for someone else. If you’re privileged in some way, someone else, whether your partner, your neighbour, or someone on the other side of the world, suffers corresponding disadvantage.

As a white man, I experience advantages that other people don’t. With my white skin, I can go shopping without being followed or harassed in other ways, as many Māori people frequently are. And as a man, I can expect my opinions to be taken seriously – more seriously, anyway, than I could if I was a woman. I also have access to opportunities that other people don’t have. I’ve had educational opportunities that have been less accessible, and inaccessible, to other people – like private secondary schooling and tertiary education.

These have given me social, financial, and intellectual advantages, and simultaneously disadvantaged those who haven’t had them. That makes it harder for them to compete with me for decent work, for example. I didn’t earn these advantages; I was ‘just lucky’. Luck’s only part of the equation, though. These privileges can’t be explained away as ‘accidents of birth’. They’re also consequences of what bell hooks calls ‘white supremacist capitalist patriarchy’, which we can do something about.

Privilege is a political issue because it’s a consequence of collective organisation. It also connects to what are generally thought of as political issues – for example, reparations for historical injustices (in his essay ‘The Case for Reparations’, Ta-Nehisi Coates conceives of reparations not only in monetary terms, but also in terms of acknowledgement). The problem of privilege is, however, fundamentally ethical. It concerns how all of us, whatever our circumstances, act as individuals, with respect to both ‘private’ and ‘public’ matters. It’s a problem we can solve.

In May last year, Max Harris and I published an article called ‘The Politics of Love’, in which we argued for a values-based politics, inspired by love. The Politics of Love, with its commitment to equality, can help address privilege – in part because it recognises that the political is ethical.

In that article, we wrote:

We think love encourages us all to care about politics. If love involves a concern for people, then a politics of love will move this world to a better place for everyone. [...] This point can be brought out negatively: if we fail to resist racism or sexism, issues that are largely political, we cannot be said to be loving, we cannot be said to care about people. If we are committed to changing the structure of our society, politics must be part of the project; and if politics is going to do the work of love, it will be because we as individuals care enough to ensure that it does.

I believe the way we’ll dismantle privilege is through understanding.

In those instances where privilege was successfully challenged – for example, when women’s suffrage was realised – it was because the oppressed demanded change. What’s less widely recognised is that, in all of these cases, power was also ceded. This happened because those with power came to, or were made to, understand. By ‘those with power’, I don’t just mean those who held political office – I mean all of those with power, including voters, as well as those who influenced them. Power’s diverse, and persuasion itself is powerful. People will cede power to bring about justice, if they understand the importance of doing so – this is one of the quieter lessons of history. If we’re to dismantle privilege, we’ll need to work together to understand it, and to use that understanding.

In his book Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Paulo Freire writes that the oppressed must free their oppressors. He characterises oppression as a form of dehumanisation, and argues that rather than seeking to oppress their oppressors, the oppressed, in fighting to regain their humanity, must instead be ‘restorers of the humanity of both’:

This, then, is the great humanistic and historical task of the oppressed: to liberate themselves and their oppressors as well. The oppressors, who oppress, exploit, and rape by virtue of their power, cannot find in this power the strength to liberate either the oppressed or themselves. Only power that springs from the weakness of the oppressed will be sufficiently strong to free both.

According to Freire, the privileged are unable to liberate themselves from the false logic of oppression. In order for equality to be realised, he says, they must be freed from their privilege by those who it disadvantages.

If we want to end privilege, we’ve got to work together. It’s those who have the most power who have the greatest responsibilities, because they’re usually best placed to actualise change. But in order to understand, those who benefit from privilege must be supported by those people who suffer because of it (‘Who,’ Freire asks, ‘are better prepared than the oppressed to understand the terrible significance of an oppressive society?’). It’s important that we affirm understanding as possible, because if we don’t, those who might help us to dismantle privilege won’t be able to.

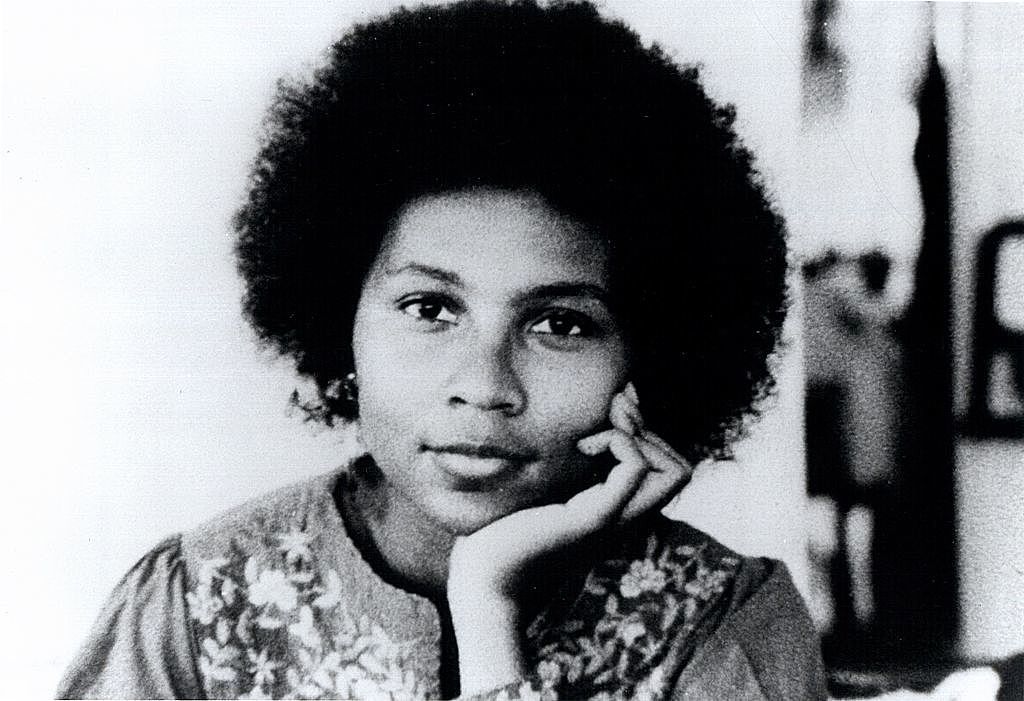

I’m inspired by bell hooks, whose redemptive writing celebrates understanding. hooks teaches with works like Feminism is for Everybody: Passionate Politics and The Will to Change: Men, Masculinity, and Love (two books that speak to me particularly clearly, as a man) that loving relations will, necessarily, accommodate all of us. Her words inspire change by imagining it as possible.

Understanding enables us to interrogate privilege, our own and other people’s; it encourages the privileged to make space for those who privilege disadvantages; and it urges us to use our privilege to challenge and help dismantle privilege. Given its importance, we should work to cultivate it.

Communication, especially when it takes place in the context of loving relationships, helps us understand other people’s perspectives. Some of the deepest insights I’ve gained into disadvantage have come through one-on-one conversations with friends who’ve shared their experiences with me. I’ve also learnt from people who share the privileges I have and are working to address them.

Power, unless it’s wrested violently, must be relinquished. Or shared.

Learning another language can also nurture understanding. I’ve learnt – and continue to learn – a great deal through my engagement with te reo Māori (having grown up identifying only as Pākehā, and just recently starting to explore my Ngāi Tahu heritage).

Perhaps the greatest resource available to us is literature. In her book Not for Profit: Why Democracy Needs the Humanities, Martha Nussbaum highlights the value of literature in fostering empathy, which can inform understanding. And in February, bell hooks and Emma Watson discussed the importance of books and reading to generating understanding and love. Similarly, the writing of thinkers like Donna Awatere and James Baldwin has helped me better understand other people’s experiences, and to appreciate the quality and limits of difference itself.

As individuals our experience is limited, but we can help each other see more than our own experiences present to us. In order to achieve understanding, we must also be committed to critical reflection with respect to ourselves, our relationships, and the world in which we live.

Privilege involves the power to ignore, and remains invisible until it’s challenged. Clear, direct critique is necessary – even when it’s uncomfortable. It’s also very important to emphasise togetherness and reconciliation. I think especially about the writing of Ta-Nehisi Coates, whose incisive commentary (in his book Between the World and Me, for example) reflects his commitment to the moral equality of all people, without compromising his critical messages. Language that’s accusatory and unsympathetic, though deeply felt, risks misrepresenting privilege as something that’s always consciously exercised. At worst, it can prevent people from engaging. People won’t feel capable of working to address their own privilege if they believe that, whatever they do, they won’t understand – that they cannot exist in loving relation to other people.

The assertion that those who are privileged cannot see beyond their privilege doesn’t demonstrate trust, and it isn’t constructive. The argument that you can’t understand another person unless you’ve directly experienced what they have is derived from an insistence on difference – one that’s been used to justify oppression, and is, ultimately, inextricable from it. And it’s wrong: you don’t need to have experienced exactly what another person has to appreciate, listening carefully, and extrapolating from your own unique experiences, their problems and perspectives. We already do this with our friends! Instead, we should emphasise commonalities, offer analogies, and celebrate understanding.

Just because we’ve often failed to do the difficult work of understanding doesn’t mean that we cannot. We need to affirm that positive change is possible, because if we don’t allow people to change, they won’t. I’m not suggesting understanding is easy. Really, it’s very difficult. I do believe, though, that it’s possible.

Power, unless it’s wrested violently, must be relinquished. Or shared. Without understanding, we’ll only distance ourselves from equality, and we risk perpetuating privilege. But if we commit to the difficult work of understanding, we can neutralise privilege and realise love.