Thirty, Flirty and Tired

In 30 essays on being 30, Nathan Joe meditates on love, identity and growing up.

1. Micro

I can’t imagine writing a long-form essay. Maybe that’s why I’ve always felt at home in the world of poetry, with its short bursts and concision. The idea of writing a single, definitive essay on being 30 seems daunting, impossible even. To turn to a form that can hold the scatter-brained expansiveness of this topic feels more reasonable. To acknowledge that writing in the time of Covid-19 is difficult, and often interrupted, feels like the most honest thing to do.

2. Birthday

Not throwing a birthday party is the easiest way to avoid feeling older.

Not throwing a birthday party is the easiest way to avoid feeling older

3. Gaysian

It is the arc (and right) of most Gay men to claim their sexuality loudly and proudly after their coming out. To barrel forward and make up for lost time. I suspect this is why we’re such partiers, so lustfully in pursuit of intimacy and touch and sex – yes, we’re men – but also because we’ve historically, politically and typically been denied these pleasures. Over-eager late bloomers finally allowed some semblance of expression.

It is the arc of most diasporic Asians to reclaim their racial identity in their 20s, too. To move from a token figure to one of many. This comes with a sort of self-interrogation or politicisation. The smelly-lunch narrative of school is replaced by the long search for roots. A rediscovery of mother tongues and family recipes.

So what is my arc as a Gay Asian man? Ill-suited to the arc of familial expectation, what is expected of me? How to describe myself when asked for a bio? Gay Chinese Kiwi. Gaysian New Zealander. Queer Asian writer. Written out like that, these descriptors always seem insufficient, like a glib casting notice for some modern sitcom destined to fade into obscurity. Labels often fail us.

How to describe myself when asked for a bio? Gay Chinese Kiwi. Gaysian New Zealander. Queer Asian writer. Written out like that, these descriptors always seem insufficient, like a glib casting notice for some modern sitcom destined to fade into obscurity

4. Defining

Meg Jay’s Defining Decade was one of many self-help books that landed in my lap in my early 20s. It throws down a gauntlet to twentysomethings to take their decade seriously. In a TED Talk that distils the book’s themes into a compact lecture, Meg closes with: “Thirty is not the new 20, so claim your adulthood, get some identity capital, use your weak ties, pick your family. Don't be defined by what you didn't know or didn't do. You're deciding your life right now.” If the 20s are about carving out definition for your life, this implies the 30s should be defined.

5. Should

I should probably have my full licence by now. I should probably own my own vehicle. I should have paid off my student loan (I’m close!). I should have done my OE. I should be thinking about buying a home. I should be Gay married. I should have a stable full-time job.

These shoulds – and their close cousins, the what ifs – these measures of an adult life, the proper adult life, haunt and elude me.

6. Blame

In a way, we’re always looking for someone to blame (or thank) for where we ended up. Eager to please, unsure of myself, I went down the path of least resistance, or the path of most praise. The path I’ve ended up on can be blamed on a series of enthusiastic English teachers; I was always predisposed to doing the thing that people congratulated me for.

At the risk of sounding ungrateful, the problem with pride and progress is it makes things seem so achievable

7. Father

By the time my father was 30, he had moved cities to help his mum with her fish-and-chip shop. He had had his first child (me). He had bought his own fish-and-chip shop, starting his own business. He had purchased his first home. He had achieved his most pressing shoulds. He followed his shoulds closely. That was his arc.

8. Possibility

At the risk of sounding ungrateful, the problem with pride and progress is it makes things seem so achievable. Before, these signposts of success held by our heterosexual counterparts seemed out of reach. Their impossibility made them wishful thinking. Unattainable dreams have transformed into attainable failures, taunting us with possibility. But, it stands to reason, if someone has fought for the right to something, then you should not waste that right.

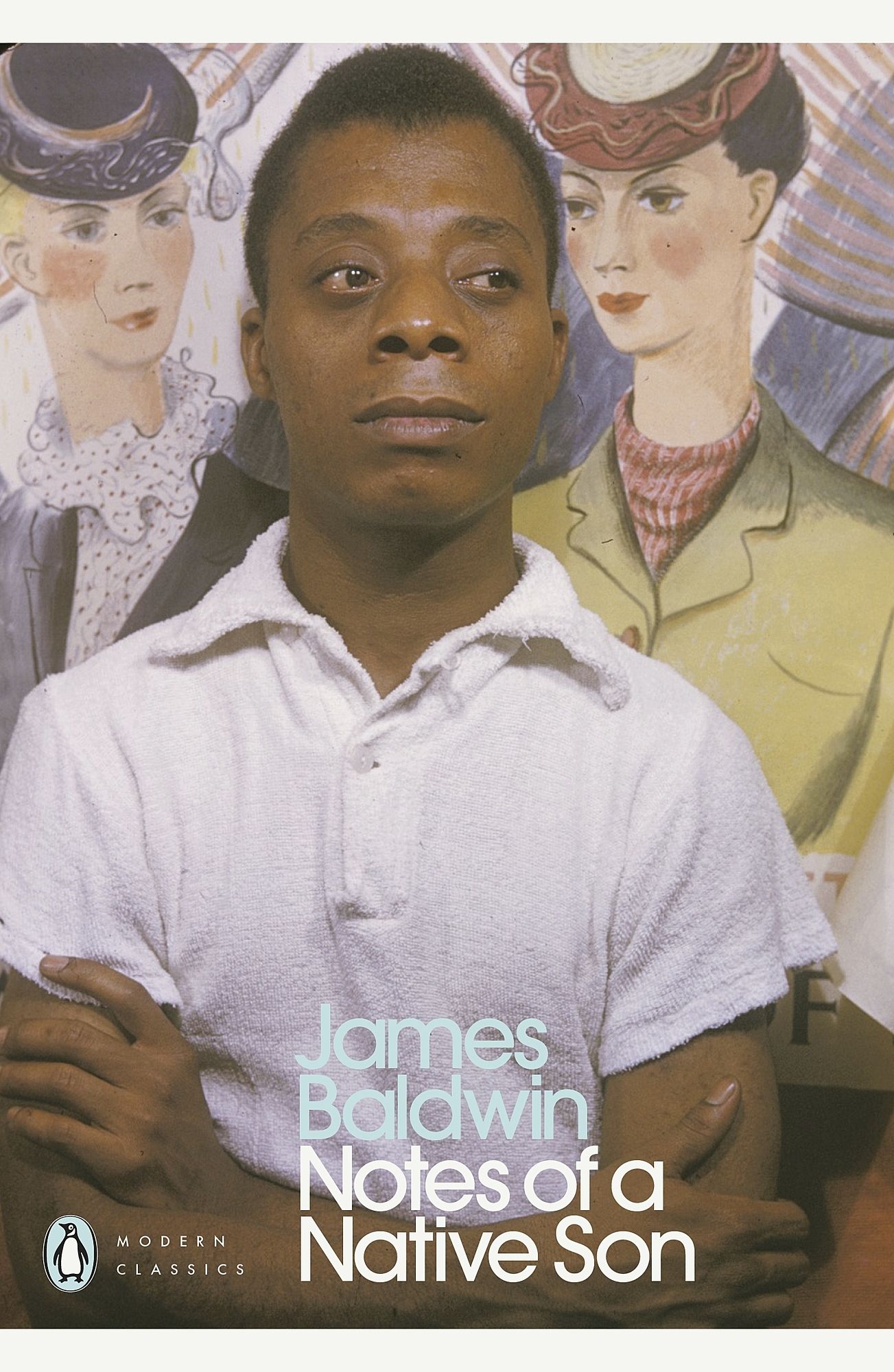

As he was for any good Queer man, for any good Gay writer, James Baldwin was one of my formative literary heroes

James Baldwin

9. Baldwin

As he was for any good Queer man, for any good Gay writer, James Baldwin was one of my formative literary heroes. In his writing, he meticulously details the landscape of his identity. Not simply identity as in identity politics, but the intersection of race and sexuality, and love and family too. In the title essay of his collection Notes of a Native Son he reflects on his relationship with his father, and their parallel experiences as African American men. He attains a sort of clarity in which he sees his father as a flesh-and-blood human, with lived experience parallel to his own. He grieves his father, but achieves some sort of peace in his writing, even if it is in retrospect.

10. Horny

In Seinfeld, there’s an episode where George jokes he can go for long periods without sex, calling himself a sexual camel, as long as he knows there is a possibility. Which is to say, I’m pretty horny, but this horniness is eclipsed by a greater sense of can’t be fucked. Once upon a time, I remember taking long bus rides across the city simply to get some dick.

I didn’t think I would still be masturbating so much

11. Masturbation

I didn’t think I would still be masturbating so much.

12. Family

For Queers, the notion of your found or chosen family being superior or more significant than blood relations is an oft-repeated one. Call it a cultural hang-up or simply filial piety, but I have never been able to sever my roots. I imagine it like a delicate game of Jenga; pulling out one piece risks upending everything.

13. Homecoming

You can’t go home any more. After all, perhaps home is not a place, as James Baldwin writes, but an irrevocable condition. I found it evocative, but never quite understood this turn of phrase from his novel Giovanni’s Room. At the age of 20, I moved away from my hometown Christchurch and settled in Auckland, sure I’d never go back. At the age of 27 I moved back home, completely unmoored by my 20s. And at 30, I’m back in Auckland once again, slowly beginning to unpack this notion of home.

14. Wunderkinds

Kate Bush produced the iconic pop song ‘Wuthering Heights’at 19. Xavier Dolan wrote and directed his first feature film, I Killed My Mother,at 19. New Zealand’s own playwright Eli Kent wrote the contemporary classic The Intricate Art of Actually Caring at age 20.

I was always obsessed with the ages of artists, growing up. I would categorise them into two camps: wunderkinds or late bloomers. Now, I look towards the late bloomers, too old to be a wunderkind. If I can’t be, say, Bush or Dolan, maybe I’ll end up like Claire Denis (directed her first film, Chocolat,at 40) or Ang Lee (directed his first film, Pushing Hands at 36).

No, as I’ve left my 20s, the real love story has been with my friends. Is that sentimental?

15. Proposal

A joking proposal by a then boyfriend on Karangahape Road, once a funny memory, now curdles in the recollection. I miss the time, or perhaps I am simply blinded by nostalgia, when a relationship was filled with such certainty.

16. BBQ Duck Café

Sam, Jenna and I sit in one of the many BBQ Duck Cafés in the city, playing easy catch-up. We land on the trite topic of romance and dating, but it’s really just an excuse to hear each other speak. No, as I’ve left my 20s, the real love story has been with my friends. Is that sentimental? To meet people with lived experience that aligns uncannily to your own makes you feel less existentially alone. Our collective ambivalence about Tinder is not just a knee-jerk response, but a shared understanding that it was never designed for us, three Kiwi Asians who’ve always existed on the peripheries of the mainstream. But we’ll always have BBQ Duck Café.

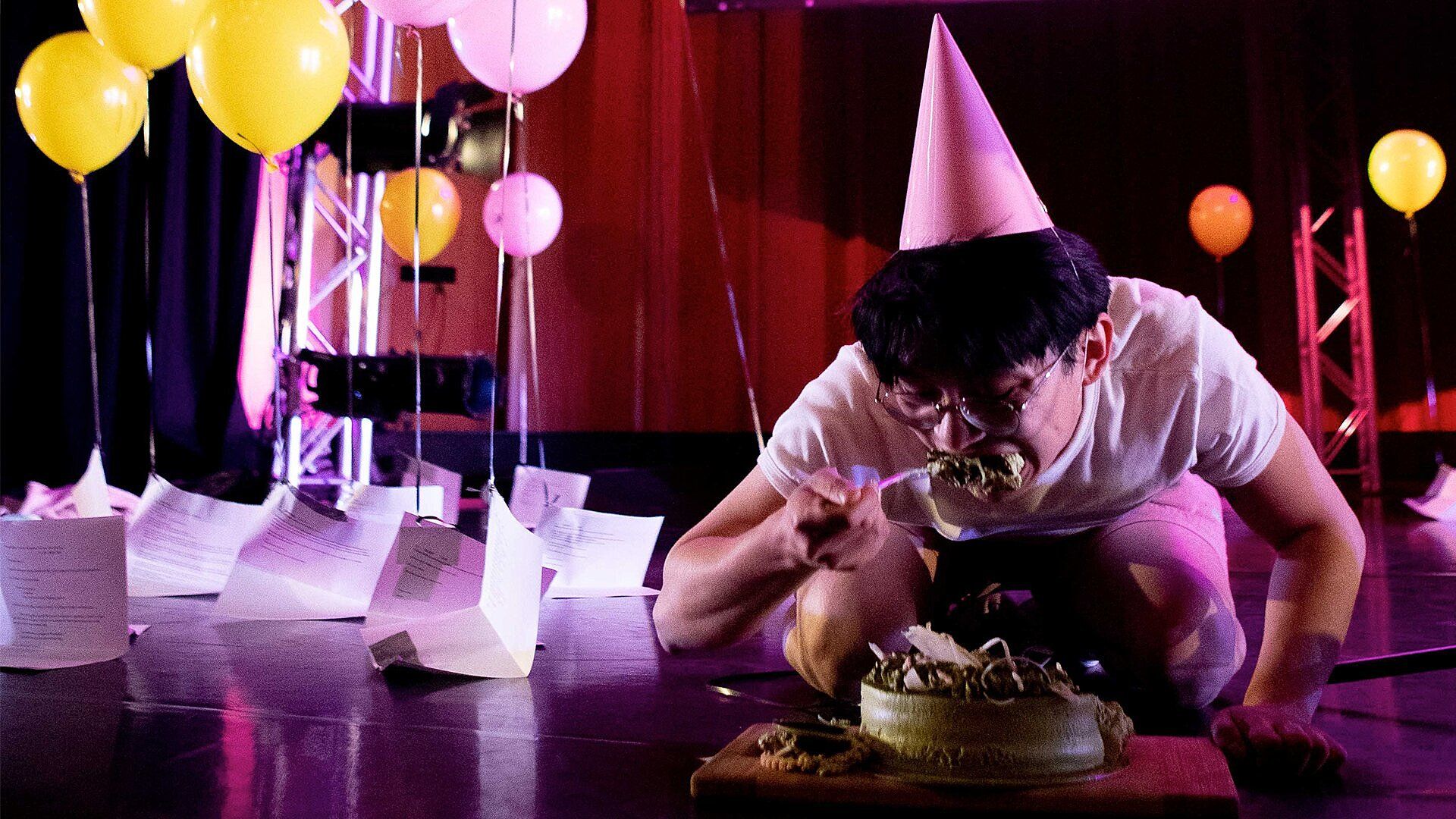

17. Party

I know an attachment to partying signals a sort of arrested development, but it’s an arrested development I never experienced in my actual adolescence. There’s a crippling pressure to be present in an age where numbness is occasionally necessary.

The other week, a doctor asked me if I’d done any recreational drugs recently. I said, “No.” Then I asked, “How recently?”

18. Recently

The other week, a doctor asked me if I’d done any recreational drugs recently. I said, “No.” Then I asked, “How recently?” She said, “Around anything from three to six months ago.” Then I said, “Oh, yeah, then yes, recently.” The point I’m trying to make is: time is relative.

19. Comedown

In my late 20s I thought I was depressed, but realised I simply had no serotonin.

20. Mum

The first time you realise your parents were young once is memorable. Of course, we understand this to be a fact. Everyone was young once. Everyone gets older. Everyone dies. And, yet, when faced with a photo album tucked away on a shelf in the corridor of your family home, you lose your breath. You can’t believe your mother ever looked so young. Before you were born. Before you came out. Before the grief of losing the son she thought she had.

It shouldn’t be such a shock to realise that you are now older than your parents once were. But somehow, it is.

That I can trace, I am something between a meatsack and stardust

21. Ex

Over the New Year, I receive an email from an ex. A sort of apology email. A sort of let’s grab coffee email. A sort of how are you doing email. The same ex that pseudo-proposed to me. In it, there’s an offer to reconnect in some way. I thank him for the offer, but gently disengage. Like backing away from the edge of the cliff, I’m reminded of that song by Of Montreal: The past is a grotesque animal / And in its eyes you see / How completely wrong you can be.

22. Get Out

SPOILER: There’s a scene in Jordan Peele’s Get Out where the main character, Chris Washington, an African American man, uncovers a shoebox full of Polaroids of his white girlfriend’s exes who bear an uncanny resemblance to him (see: Black). That is the experience of dating whiteness as a POC, to constantly be checking for that proverbial shoebox, worrying you’re just another Polaroid to add to the collection. Or, to riff on Zora Neale Hurston, I feel most coloured when your exes all look like me.

23. Astrology

In the last year, I’ve embraced my placements as a Leo sun, Scorpio moon and Scorpio rising. Whether I believe it or not (ironic engagement is still engagement), is less important than the fact that it’s a fun reprieve, a frivolous scapegoat for mapping out some sense of this chaos. Something to simply believe in. That I can trace, I am something between a meatsack and stardust.

Despite the Asian heartthrob and superhero now achieving mainstream success (here’s looking at you Crazy Rich Asians and Shang-Chi)

24. Representation

In my high-school yearbook, when asked to pick the actor who would play me in the film of my life, I picked River Phoenix. To be incredibly clear, this was a knowingly ironic choice, not simply a product of self-loathing or internalised racism (though there were definitely hints of that). This was 2009, after all, well before either Queer or Asian representation had made much headway in our pop-cultural consciousness. At this point, River in My Own Private Idaho, with his fraught relationship to home and intensely unrequited longings, was the closest thing I had to a cinematic counterpart.

I’m still waiting. Despite the Asian heartthrob and superhero now achieving mainstream success (here’s looking at you Crazy Rich Asians and Shang-Chi), it’s still River my younger self relates to. For all the progress made, Queer Asian bodies are still so absent. I’ve learnt to hunt for them elsewhere, in the margins of prose and poetry (Chris Tse, Ocean Vuong, Chen Chen).

A long lineage of Queer men. Gone but not forgotten

25. Legacy

James Baldwin – 63, cancer

Tennesee Williams – 71, choking on a bottle cap

Andy Warhol – 58, cardiac arrhythmia

Larry Kramer – 84, pneumonia

Rock Hudson – 59, AIDS

Harvey Milk – 48, assassinated

Derek Jarman – 52, AIDS

Christopher Isherwood – 81, cancer

Yukio Mishima – 45, seppuku

Keith Haring – 31, AIDS

Leslie Cheung – 46, suicide by jumping off building

Rainer Werner Fassbinder – 37, overdose

David Wojnarowicz – 37, AIDS

A long lineage of Queer men. Gone but not forgotten. I think of how profoundly sad all my heroes and the legacy I come from are. That the sad old Gay is a cliché, is a cliché for a reason. I wonder how differently I would have turned out with happier Gay role models to look up to. I wonder where I would have found them.

You seethe with jealousy when you see how emotionally articulate the baby Gays are. You wish you had grown up 10 years later

26. Envy

You seethe with jealousy when you see how emotionally articulate the baby Gays are. You wish you had grown up 10 years later. But this envy, you realise, is the shape of progress.

27. Neutral

Striving for a perfect state of peace or harmony, I like to think of my body as neutral, neither skinny or fat, old or young, simply being. That would be the ideal. Unfortunately, I’m not a fucking Zen buddhist.

28. 13 Going on 30

I am Jennifer Garner getting what she wished for. I am Jennifer Garner waking up and wondering how I got here. I am Jennifer Garner desperately seeking Mark Ruffalo to help turn back time. I am Jennifer Garner, with the job I’d always wanted, but it not quite being what I had imagined. I am Jennifer Garner, shocked to see a dick for the first time (okay, not that one). I am Jennifer Garner, a teenager trapped in a grownup body. I am Jennifer Garner.

You were in awe of those who could turn thought into words into sentences into connection. And that is now the very thing you do

29. Old

Is there anything more irksome than someone young bemoaning their age? It seems navel gazing, self-indulgent, disingenuous to call yourself old at 30. But when I say old, what I mean is mortal. What I mean is, I feel closer and closer to my body, my sense of the years remaining. To say I feel old is to say I am profoundly aware of my own death, but don’t know how to articulate it. I do not believe in an afterlife. I do not believe in resurrection. I believe in soil and ground and earth. All I know is I am afraid of something I never used to think about. At what age do you earn the right to feel old?

30. Now

If you could see yourself now. (You being 13-year-old Nathan.) Okay, maybe not necessarily right now behind a laptop slogging away under the tyranny of editing. But the general now. Remember what he was after? Something akin to freedom. Something akin to pride. Not the pride of your early 20s, as nice as that was. No, not the pride of rainbow flags or even the pride of great sex. No, the pride that started it all. That started with reading a sentence. The intimacy of a stranger’s words bringing you out of your lonely meadow and connecting you to an entire culture. Where everything fell away and all that was left was pages. You were in awe of those who could turn thought into words into sentences into connection. And that is now the very thing you do. Now that’s an arc.

Feature image: Petra Mingneau