Ko Toi Tū, He Taonga Mō Tātou

Art historian and Associate Professor Ngarino Ellis on why Toi Tū Toi Ora: Contemporary Māori Art, the largest exhibition in the 132-year history of Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, is an exhibition for us all.

.

“I would like Māori to feel that the show was speaking to them and their understanding of a Māori worldview first and foremost before any conversations about 'art history' or the to and fro of art making.” – Nigel Borell

A disclosure before I start this review – my mother, Elizabeth Ellis, is an artist in the show, as is my godmother, Mere Harrison Lodge, and her sister, Kāterina Mataira (O Hine Waiapu marae represent!). Another disclosure – my mother was the Chair of Haerewa, the Māori Advisory Group to Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, a position she enjoyed for just over 25 years. However, by the time this review is published, the composition (and perhaps even the existence) of Haerewa will be changing radically, as most of the members have resigned. But that is another kōrero.

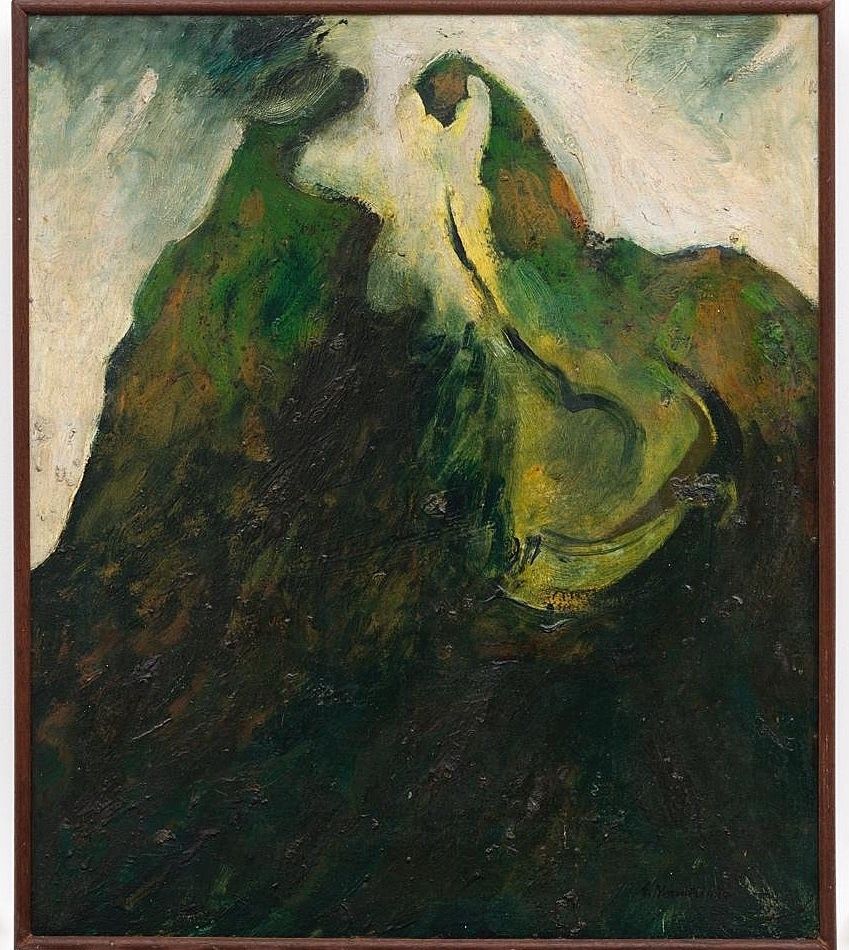

Elizabeth Ellis, Puke Huia, 1966. Oil on hardboard. Courtesy of the Mountain Ellis Whānau.

I should have known that Toi Tū Toi Ora: Contemporary Māori Art was going to be a different kind of show, based on the media preview. These viewings are typically modest affairs, held in the Friends’ Lounge, where carefully curated kai (sushi and Asahi for the recent Enchanted World Japanese print exhibition) is offered, along with a talk by the curator and (most precious of all) an uncrowded advance viewing of the show.

What a different affair the Toi Tū preview was!

My PhD student Justine and I arrived to a room packed with a wonderfully distinctive group of people. Were they all there to ‘write reviews’? Probably not, but they were there to support Nigel, the show, and the kaupapa. The oysters slipped down easily with the champagne, and then we were shepherded into the auditorium where Brook Konia, the exhibition intern, opened the event with a karakia. Nigel then spoke briefly, followed by the showing of a wonderful short film directed by Chelsea Winstanley, stimulated by the show. And then it was off upstairs to view the exhibition.

Toi Tū is the kind of show I have been waiting to enjoy in Auckland for over 20 years. Spanning a phenomenal three floors of the Gallery, the show features over 100 artists, and 22 different themes woven throughout the space. It is ambitious and exhausting, both physically and emotionally.

Mere Lodge, Te Toka-a-Torea, 1963. Bronze with wooden base. Courtesy of the artist.

The exhibition begins on the ground floor, appropriately with Te Kore: The Nothingness before the Night. Before the separation of our grandparents Ranginui and Papatūānuku. Moving through the eight themed areas, the viewer learns about essential whakapapa concepts that play out like vines across the galleries. Bob Jahnke’s neon light works in the first room have become selfie central for Māori visiting the Gallery, with their luminescence radiating across the floor.

Further round, Lisa Reihana continues to set new standards of excellence with her latest work, Ihi (2020). This holds court in the centre of the Separation of Ranginui and Papatūānuku room, with its two-metre-high double-sided video screen drawing you in with its spectacle, the beautiful and ethereal figures moving and dancing.

There are so many highlights that it is better to think of the show as a multi-visit commitment. The experience should not be rushed and, if possible, attendance should be with different groups of people who can shape your understandings in different ways. I enjoyed Ngaahina Hohaia’s Paopao ki tua o rangi (2009). With poi as the key motif of Parihaka and its story of resistance to Crown invasion, the sound and photographic projection creates space for contemplating these histories. Shona Rapira-Davies’ Nga Morehu (1982–1988) are rarely seen in Auckland, and their presence on Level 1 anchors the Kei te Eke Panuku te Wahine | Women Far Walking room.

Every room delights the viewer with new sensory, visual and emotional experiences, from painting and sculpture to weaving and installation, with an equally varied range of materials: glass, toroa feathers, cardboard, tōtara, glitter paint. These things announce unreservedly that Māori art is not one thing, one idea, but rather is the result of exploration, experimentation and creativity.

The exhibition’s breadth and depth encourage multiple readings: we could see this as an exhibition of Māori art, showcasing all that is wonderful about recent art production. On a curatorial level, the energy required to generate the concept, create and motivate a team (including Taarati Taiaroa, Assistant Curator, Māori Art, and Brook Konia), liaise with stakeholders and those in the Gallery, and bring an exhibition of this size to fruition is truly remarkable. That there was only one Nigel (though he does have a twin) driving all this is a testament to his resilience and commitment to the artists, if nothing else.

The exhibition, which heralds a new era of show-making, is the result of years of tenacity by Nigel. Not only has he brought together over 100 Māori artists on site, but he has led a busy education programme both on site (such as artist talks and dance performances), and at Britomart, a 20-minute stroll from the Gallery. There, four new commissions bring Māori art to the busy area.

Lisa Reihana, Ihi, 2020. Courtesy of Regional Facilities Auckland.

Toi Tū can be considered a cornerstone of Māori art history, as it activates important concepts central to this discipline. Mana, for instance, is obvious throughout – the mana of the artists involved, especially those of the ‘first generation’ of contemporary Māori artists, who are the pakeke of the show. Their practice has laid a path for younger and newer artists to emerge. By virtue of the subject matter, many artworks are imbued with tapu – especially those depicting our ancestors. And the idea of a continuum – of moving through time and space with ease – is in every room. There is no breaking with the past. This is probably nowhere more present than on the mezzanine level, where works by Shane Cotton, Arnold Manaaki Wilson and Emily Karaka are interspersed with those regularly seen at the Gallery – gilt-framed European paintings. These rooms build on a strategy not used enough in galleries, of juxtaposing artworks originating from very different cultural perspectives. For the art history student, this is a thrill, cheeky in its mere presence – what might be the relationship between a Māori modernist sculpture and an oil painting of Christ next to it? These questions characterise the show, making the viewer want to return time and time again.

Whakapapa is a central concept throughout, as the works and thematic areas vacillate between the spiritual and ancestral realms. Nigel has featured whānau relationships across galleries: Ngāti Porou cousins (my mother and her cousins) on the top floor, the Taepa whānau (father Wi, the ceramicist, and sons Kereama and Ngataiharuru), the father and son Fred and Brett Graham, and Cliff and Gary Whiting. Their presence and work remind us of the traditional ways in which art was created within whānau for the wider community’s enjoyment.

There is teacher-student whakapapa across the exhibition: Bob Jahnke’s Toioho ki Apiti programme at Massey University (Areta Wilkinson, Rangi Kipa, Bridget Reweti), Selwyn Wilson at Bay of Islands College, Kawakawa (Elizabeth Ellis, who herself taught Emily Karaka at Auckland Girls Grammar), and Selwyn Muru, Kura Te Waru Rewiri and Brett Graham all taught at Elam School of Fine Arts, the University of Auckland where others also graduated (Lisa Reihana, Rona Ngahuia Osbourne, Ngahuia Harrison). The list goes on.

Kāterina Mataira, Moko I (1977). Acrylic on hardboard. Courtesy of the Mataira whanau.

Some minor quibbles: it was disappointing that the catalogue planned for the show did not eventuate, but ultimately the focus was getting the show up and then encouraging others to write about it, which they have in droves (such as John Daly-Peoples, Leonie Hayden for The Spinoff, and Megan Tamati-Quennell for Art New Zealand [forthcoming]). I also wondered why there were not more arts from the marae, such as tukutuku from dyed harakeke or pou/carved panels. Certainly, these arts have been very active over the last 70 years. Several of the artists included in Toi Tū have also done work for the hau kāinga, such as Bob Jahnke, Kura Te Waru Rewiri and Cliff Whiting (and even Nigel himself).

Yet this is also the attraction of Toi Tū – it is impossible to cover everything and everyone, and to do so is not only unfeasible but greedy. It does not allow for any other kind of Māori exhibition to be produced. Not including some artists and forms leaves open the possibility of more exhibitions of Māori art – let’s just hope Auckland Art Gallery doesn’t take as long next time between shows.

Nigel’s 2021 dance card is filling up, including creating new paintings for the exhibition Nine Māori Painters (9 February to 6 March at Tim Melville Gallery)and teaching an Honours paper, Indigenous Peoples and Museums, at The University of Auckland. He looks forward to spending more time writing, perhaps as part of a doctorate (this may be more my aspiration at this point than his).

Ngā mihi aroha ki a koe Nigel mō tō māia, tō mau i te moemoeā o Haerewa, ō tātou te iwi Māori. Toi Tū is a celebration for us as Māori to have space where we can enjoy art as Māori.

The final words go to him: “Māori are at the helm of telling our art stories and visions and generously afford another, new way to view the world, art history included.”

Toi Tū Toi Ora: Contemporary Māori Art

Auckland Art Gallery

5 December 2020 — 9 May 2021

Feature image: Toi Tū Toi Ora: Contemporary Māori Art (installation view), Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, 2020.