He Toka Tū Moana a Robyn Kahukiwa

Mya Morrison-Middleton reflects on the career of renowned Māori artist Robyn Kahukiwa, and her latest exhibition 'Tangata Whenua', which showed at Season Aotearoa in Auckland and Christchurch's Centre of Contemporary Art.

“Māori are tāngata whenua of Aotearoa and always will be.” – Robyn Kahukiwa, 2005

This quote comes from commentary by Kahukiwa on her 1980s painting series of the same name, Tangata Whenua. The basis for being tangata whenua is tūrangawaewae – the place we have rights, thorough whakapapa, to stand and live with autonomy. Many of us Indigenous people already know this (and are trying our hardest to live it). All Māori have a right to stand and thrive on our tūrangawaewae, on our whenua.

Robyn Kahukiwa (Ngāti Porou, Te Aitanga-a-Hauiti, Ngāti Hau, Ngāti Konohi, Te Whānau-a-Ruataupare, Te Whānau-a-Te Aotawarirangi) is an artist whose work is a mighty force against the cold grip of colonial occupation in Aotearoa and Te Waipounamu. Kahukiwa has been contributing her skills for decades across many artforms – predominantly painting but also sculpture, drawing, printmaking and illustrations – to share Māori stories with purpose.

Kahukiwa is in her 80s, and remains steadfast in her practice. In 2023 a survey of her work featured in the Sharjah Biennial in the United Arab Emirates; in 2019 she was a core part of the Kia Mau group protesting the celebrations of the 250th anniversary of the HMS Endeavour arriving on our shores; and she contributed artwork for the cover of Tina Ngata’s 2019 book Kia Mau: Resisting Colonial Fictions.

The basis for being tangata whenua is tūrangawaewae – the place we have rights, thorough whakapapa, to stand and live with autonomy.

The following year, Kahukiwa won Te Tohu Aroha mō Te Arikinui Dame Te Atairangikaahu at Creative New Zealand’s 34th Te Waka Toi Awards. Looking beyond her career accolades, and closer to our homes, Kahukiwa has illustrated the books that many children in my generation were raised on. These picture books were a rarity at the time for their familiar images of this land, our people and our stories.

So, while I looked like a casual gallery visitor from the outside, on the inside I was elated with admiration and gratitude to stand in an exhibition of recent mahi toi by Kahukiwa.

The exhibition Tangata Whenua opened at the Centre of Contemporary Art Toi Moroki (CoCA) in Ōtautahi in November 2023, touring from its debut at Season gallery, Tāmaki Makaurau, earlier in the year. The works in Tangata Whenua are recent – most were made in 2022 and 2023, the oldest is from 2015.

The curators made sensible use of the single, humble gallery space, as CoCA is currently programming only in the ground-floor gallery of its multi-level building. The entrance was filled with a cushiony reading and colouring-in area loaded with a back catalogue of Kahukiwa’s illustrated books, borrowed from Christchurch City Libraries Ngā Kete Wānanga o Ōtautahi. Copies of Kahukiwa’s latest book, Taranga, were displayed by the reading area. The gallery then opened out to two long walls lined on either side with artworks.

Robyn Kahukiwa, Tangata Whenua - Cause and Effect, 2023, Season Gallery, Sept-Oct 2023, Photographer Samuel Hartnett

On the left side were five painted works, with bold text and people in scenes that merged past and present. These showed the active process of colonisation, and the current consequences for Māori.

One painting, Cause and Effect (2023), is a convergence of a historical Māori man being shot by a British naval officer with a scene of a present-day person sitting on the ground holding out a cup for change. The watercolour work Violence Then and Now (2019) blends a historical scene of a British soldier on horseback fighting Māori with a present-day woman being tackled by a black-suited man. He is issuing her a child-removal order from CYFS (read: Oranga Tamariki), his hand grasped around her baby’s wrist.

It’s hard to be with these works for too long. The feeling of despair and grief they bring up is relentless. They are jarring reminders of all that has been lost or, more accurately, taken, and the pauperisation of Māori. But I appreciate how firm they are in depicting the truth. They don’t allow any room to hide from the ugly foundations that New Zealand is built on. The painful past and present won’t be avoided here.

It seems timely, in light of the leaked Treaty Principles bill draft by the current government, to be drawing focus to the successive failures of New Zealand and the Crown to uphold Te Tiriti. But Tangata Whenua illustrates that the Crown failing to uphold promises is old news, and that these breaches of Te Tiriti will continue to be the root cause of issues affecting Māori until our full sovereignty is restored.

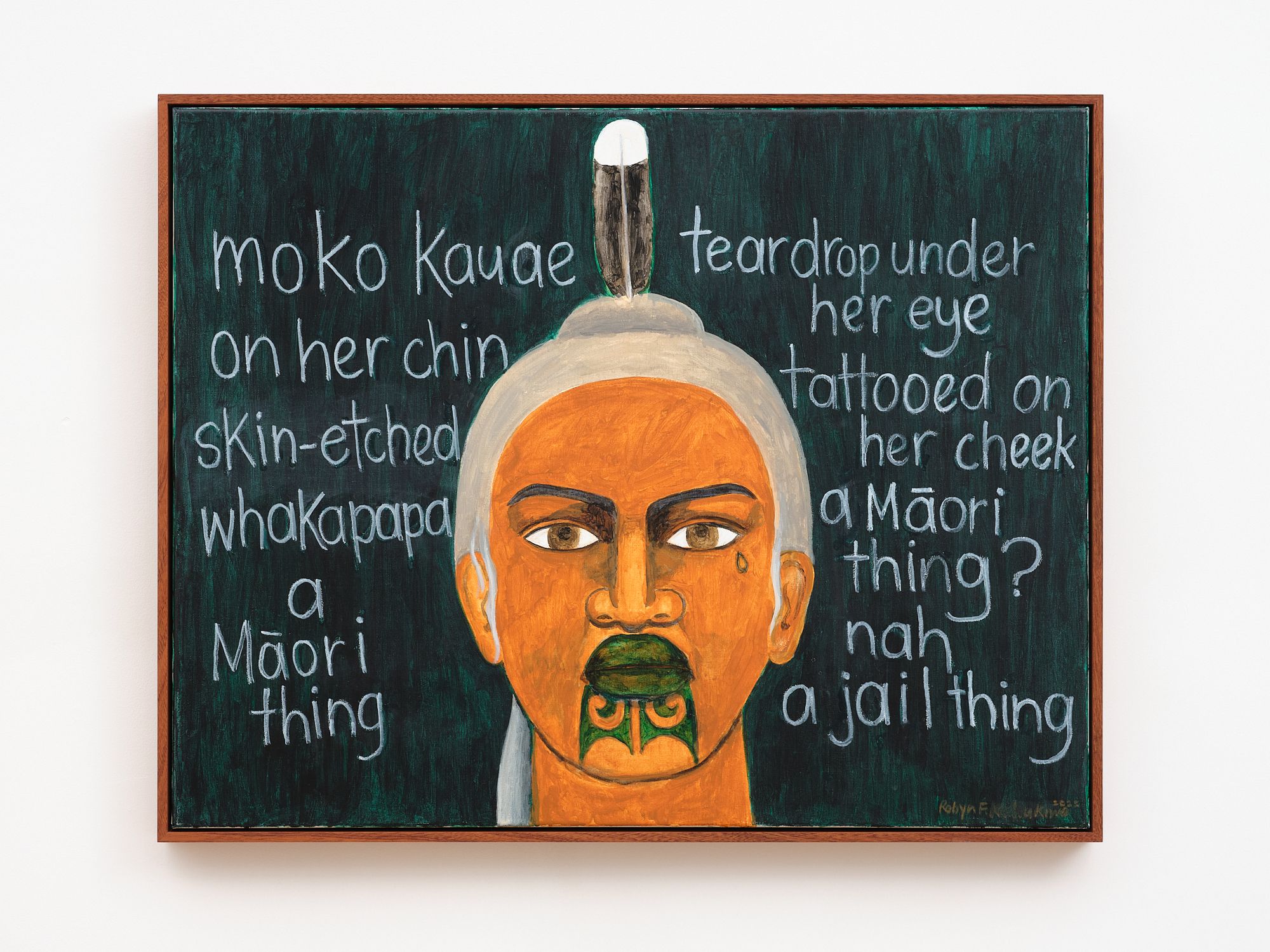

The exhibition pamphlet emphasises that Tangata Whenua is Kahukiwa’s first solo show in Te Waipounamu in two decades. The significance of this exhibition being in Ōtautahi wasn’t lost on me, either. In the first painting, Survivor (2022), a woman adorned with a moko kauae and a teardrop tattoo is framed by the text “teardrop under her eye tattooed on her cheek a Māori thing? nah a jail thing.” Next to that, in Incarcerated (2022), a woman behind bars is overlaid with the graphic statement “Māori are the most incarcerated Indigenous people in the world.” The over-incarceration of Māori, especially Māori women, feels like an appropriate issue to bring up in Ōtautahi, the location of one of three women’s prisons in the country, and the only in Te Waipounamu.

Robyn Kahukiwa, Tangata Whenua - Survivor, 2022, Season Gallery, Sept-Oct 2023, Photographer Samuel Hartnett

The works on the opposite wall are cropped closer around individual figures. The 2023 Sovereign series of pencil drawings features lone women staring out, each with an expression that I don’t know how to describe, but I can instantly recognise. Each woman has different hair and eye colours, but all are adorned with identical moko kauae, tear-drop tattoos and huia feathers in their hair. They are each flanked by a maunga, an awa, a flying United Tribes flag, and a soaring male huia overhead.

In these works, Kahukiwa correctly reaffirms the sovereignty of these women. As George Watson says of her portrait technique, “[Kahukiwa] draws on a long tradition of the use of the figurative in Māori art, where tangata whenua are understood as expressions of the land, and of our ancestors.” Their surroundings read like visual expressions of their pepeha, testifying to the descent that gives them connection to, and authority within, their tūrangawaewae. Following this, all tangata whenua should have the option to live by Māori justice processes and principles on their tūrangawaewae, without imposition of imported justice systems.

In her book Kia Mau, Tina Ngata opens with the statement: “To be born Indigenous is to be born into a political reality.” Tangata Whenua is unwavering about the horrors and injustices of this political reality. The women Kahukiwa has painted could be multiplied by thousands to represent Māori currently incarcerated. Māori made up 54% of the prison population as of June 2022, when the total number of incarcerated wāhine Māori was 4108. If we look at these statistics within a whakapapa lens, like Kahukiwa is doing, the number of lives scarred by the New Zealand justice system is even greater.

The pū harakeke framework is Māori genius. Weavers will know this as a foundational idea put in practice to protect the health of harakeke plants when harvesting. The surrounding awhi rito (parent) harakeke leaves support and protect the central young shoot (baby) so it can grow tall and strong. The health of the pū harakeke (and wider pā harakeke) can continue as each new generation grows from baby to parent, to grandparent. We consider the pū harakeke as a whānau, and would never cut the awhi rito away. But my lasting question from looking at these works is: what happens to future generations when human awhi rito are cut away, by being imprisoned? Or made homeless?

Robyn Kahukiwa, Tangata Whenua - He Whakaputanga, 2023, Season Gallery, Sept-Oct 2023, Photographer Samuel Hartnett

One pencil portrait, Upoko (2023), is a similar form to the Sovereign series, but rather than showing pepeha touchstones, such as maunga and awa, the lone figure is escorted only by a huia – our deluxe yet extinct kaitiaki and messenger between realms, with feathers that communicate mana and rangatira status. This reminds us that even Māori who do not yet know their whakapapa intimately still have a right to stand and be acknowledged as tangata whenua.

Although these pencil drawings depict confronting subjects, they are my favourite in the show. He toka tū moana, like a rock standing firm in the sea, they affirm, without glorifying, the strength that individual Māori women pull from our tūpuna and whenua, to weather everything that colonisation confronts us with. Much like the familiar but hard-to-describe expressions of the painted women in the room, Tangata Whenua presents both familiar conditions and known histories of so many Indigenous people. Why do we have to continue to describe what we’re constantly living in? Is it redundant, like saying water is wet? The exhibition shows explicitly that reality must be faced, while balancing both the joys and the horrors. There is an empowering understanding gained from confronting reality, rather than hiding from or being consumed by it.

Robyn Kahukiwa, Tangata Whenua - Installation shot Ō Papa Gallery, CoCA Toi Moroki, Nov 2023-Jan 2024, Photographer Owen Spargo

In the accompanying essay to the exhibition by Reina Kahukiwa (Ngāti Whakaue, Te Arawa, Patuheuheu, Ngāti Haka, Tūhoe, Ngāti Porou, Rongowhakaata, Ngāi Tamanuhiri, Te Aitanga-a-Mahaki), she writes about how, as a child, Robyn would lie on the floor of her family home and draw horses with coloured pencils. The coloured-pencil drawings, and references to hapūtanga in the room, are reminders that nurturing the next generation is at the core of decolonising or, the more recently popular approach, re-indigenising.

Te Whaea me te Tamaiti (2022) shows a woman staring out to the distance as she holds a baby, who is reaching out and pulling her veil of blue-streaked black hair closer. This work pulls gentle attention to a tender moment. Coloured pencils are often overlooked as a medium, perhaps because they are easy to use, child friendly, and can’t render the same vivid consistent colours as paint. Kahukiwa is known for her vibrant paintings, but her pencil drawings are my favourite here. The technique is freer and each line is visible as she builds the pigment and fades it out. I associate Kahukiwa’s drawings with all the precious food-smeared drawings by beloved babies hanging above my desk and stuck to my fridge, or sitting with a baby in my lap who is passionately colouring in Pokémon – the routine moments I store as reminders of my undercover motive to persevere, mō ā tātou mokopuna.

The book Taranga (published in 2023, authored by Reina and illustrated by Kahukiwa) has accompanied the exhibition as it tours, doubling down on the gravity of hapūtanga in the room. Taranga is an approachable retelling of Taranga giving birth to her son Māui-tikitiki-a-Taranga.

Reina’s poetic text echoes the metaphors and tempo of various karakia and whakataukī. Paired with Kahukiwa’s velvety illustrations, printed onto friendly matt paper (no annoying glossy glare interfering), it reads like a guide to birthing practices of te ao tawhito. During the birth, Taranga draws on the strength of her tūpuna, seeks reassurance from kaitiaki, and is aided by atua Hine-te-iwaiwa.

Practices and knowledge derived from te ao tawhito around childbirth and child raising are both attractive to and effective for Māori whānau to enhance collective wellbeing. This was a key takeaway from the development of wahakura (harakeke woven bassinets) as a tikanga effective for SUDI reduction, a topic covered in the book Tiakina te Pā Harakeke: Ancestral Knowledge and Tamariki Wellbeing (2022). Similarly functional, Reina’s retelling of this story holds old knowledge, laid out skilfully to be adapted into current practices. This could be said for the exhibition as a whole – it is a pātaka of old knowledge offering to sustain us.

In 1986 Kahukiwa said, “having children triggered off the desire and need to express my feelings in paint.” Since visiting Tangata Whenua and reading Taranga, this quote has stuck with me. Of course having children was the catalyst to her making art. Kahukiwa has decorated the world with Māori stories, old and new, as an enduring resource for her children and for generations of children. Although Tangata Whenua has elements of hard truth, it is bound with a genuine warmth that infuses visitors with the strength and tenderness they need to move in the world.

Robyn Kahukiwa, Tangata Whenua - Te Whaea me te Tamaiti, 2022, Season Gallery, Sept-Oct 2023, Photographer Samuel Hartnett

Tangata Whenua is a smaller-scale offering compared to many of Kahukiwa’s famous large-scale pieces. It is a body of work tightly focused on themes of incarceration, homelessness, sovereignty, tūrangawaewae and hapūtanga. The tight focus and scale of the works offer a generous demonstration of how Kahukiwa works with repeated forms, composition and materials across a web of ideas. Observing Kahukiwa’s approach and output in Tangata Whenua offered a space to reflect on her wider career.

Kahukiwa had two solo exhibitions in the 1980s also titled Tangata Whenua, and while there aren’t vital parallels to draw between these shows, it shows the timeline of her career. She has been a practising artist since the 1970s. That’s over 50 years of prolific high-calibre work. The retrospective book The Art of Robyn Kahukiwa was published in 2005, with in-depth biographical essays and a huge collection of photographs of her work. And in the nearly 20 years since then, Kahukiwa’s output has not faltered. Tangata Whenua is evidence of that.

Robyn Kahukiwa, Tangata Whenua - Violence Then and Now, 2019, Season Gallery, Sept-Oct 2023, Photographer Samuel Hartnett

Hints have been dropped of an upcoming survey of Kahukiwa’s work by the National Portrait Gallery, in their recent hunt to locate missing works from Kahukiwa’s Wahine Toa series. Sitting in Tangata Whenua, taking stock of those 50 years, I wondered when the next major Robyn Kahukiwa exhibition and book would happen?

Retrospectives and artist’s books bring a critical mass of research, attention, celebration and historical record to an artist’s work. In the past few years we have seen major retrospectives of Ralph Hotere (Te Aupōuri), Selwyn Muru (Te Aupōuri, Ngāti Kurī), Wi Taepa (Te Arawa, Ngāti Whakaue, Te Āti Awa), Sandy Adsett (Ngāti Kahungunu, Ngāti Pāhauwera), Robin White (Ngāti Awa) and Marilynn Webb (Ngāpuhi, Te Roroa, Ngāti Kahu), so hopefully a standard is being set that Māori, and especially wāhine Māori, artists are to be celebrated with the same respect as their Pākehā counterparts. It will need to be, because there isn’t another living artist whose impact compares to the iconic, widespread and enduring influence māreikura Robyn Kahukiwa has had on this country.

Further reading:

Kahukiwa, Reina. “Ka Mua, Ka Muri: The Art of Robyn Kahukiwa.” In Tangata Whenua exhibition pamphlet. Auckland and Christchurch: Season and Centre of Contemporary Art Toi Moroki, 2023.

Kahukiwa, Reina. Taranga. Auckland: Little Island Press, 2023.

Ngata, Tina. Kia Mau: Resisting Colonial Fictions. Wellington: Kia Mau Campaign, 2019.

Tipene-Leach, David, and Sally Abel. “Wahakura and Te Whare Pora o Hine-te-iwaiwa: Delving Deeply into Te Pā Harakeke.” In Tiakina te Pā Harakeke: Ancestral Knowledge and Tamariki Wellbeing, edited by Jenny Lee-Morgan and Leonie Pihama (Wellington: Huia, 2022), 177–187.

This essay has been supported by Public Interest Journalism, funded by NZ On Air.