The Dark Intimacies of Online Romance in Natasha Matila-Smith’s Artwork

Huni Mancini delves into obsession, intimacy and loneliness in Natasha Matila-Smith’s artwork.

Sometimes we reveal our darkest desires online, safely hidden behind the veil of the screen. Huni Mancini delves into obsession, intimacy and loneliness in Natasha Matila-Smith’s artwork.

I sift through the images and texts on her website and Instagram account, looking at her body of work. This distance leads me to create my own vantage point, imagining how they might have looked in person, and how I may have responded when confronted by them. Against the bright light of my laptop screen they have the appearance of dark voids. While squinting to see their subtle folds from the flatness of my screen, I wonder, is distance the secret to getting closer?

Natasha Matila-Smith’s art practice explores the boundaries of online intimacy. Intimacy is characterised by familiarity or closeness with a person, a thing, or an idea. It stems from the Latin intimus, meaning inmost, innermost, deepest. It is also used figuratively to speak of emotions and affection, and to denote a close friend.1 Through a body of confessional textile works that has developed over time, Natasha uses a range of surfaces to verbalise unspeakable emotions about romantic longing. In revealing the cross-current between outer and interior spaces, she tells a story of how colonial capitalism is embodied in intimate ways.

Natasha, who is of Ngāti Kahungunu, Ngāti Hine, Sale'aumua and Pākehā heritage, resists definition by colonial or romanticised pre-colonial standards. Based in Tāmaki Makaurau, she’s written extensively about the impulse of New Zealand art institutions to define and exoticise Indigenous bodies and cultures. By raising discourse around the disconnection between digital interfaces and their underlying structures, she’s also suggesting the disconnect is so intuitive; it’s the tacit knowledge that governs and connects us all. Her art practice therefore abandons any reference to an ‘authentic’ cultural heritage or depth of history, instead adopting a language that is at once personal and universal. Her urge to address her own hidden emotional landscape implies that bodies have a history of their own.2

Natasha speaks from her position as an Indigenous woman of colour (WOC), a position where multiple sites of oppression intersect and are intimately related to the body. She uses her art to vocalise this position, developed out of a desire to connect with others. She explains:

I wanted people to understand what it’s like from a personal level to be a fat WOC with everyday issues not relating to feelings of displacement. Ofc those feelings are there but I’m more than racial oppression…I’m also bodily and gender-related oppression. 3

Since 2016, she’s developed a series of confessional works that explore her experiences of loneliness and discomfort, and how they relate to larger social and economic structures. In group shows such as Between You and Me (2018), and If you miss me, let me know (2018), her soft façades intersected the gallery, allowing the viewer to weave themselves through the empty space and piece together a narrative depending on their access point. These shows have told a story of the self as mutable, complex and almost always mediated by objects within a virtual milieu.

Within these works the spectre of her body often appears, inviting the viewer to ‘peek behind the curtain’ into a space that’s porous and delicate. Like whispers of a crush shared with a friend or diary entries lamenting a broken heart, the fragility she shares ignites “the strange ambivalence which lies at the heart of intimacy, caused by its complicated relationship with public and private spheres.”4 And just as confessions are online, her confessions present in these artworks are filtered through a kind of veil.

The confessional has religious origins, most popularly associated with the Roman Catholic church. Inside a private, darkened booth the individual confesses their sins to a priest who is separated by a latticed veil to keep both their identities hidden. In a religious context, the practice of veiling alludes to a relationship between the figure and the space they occupy. The veil can draw a line between public and private space, or dissolve it.

In an Islamic cultural context veiling can be seen as strategic. It enables women to navigate a complex dialectic of social, political and personal conditions.5 As Reina Lewis writes, an economy of gazes filter through the veil, and these physical manifestations are as varied as the social, historical and cultural contexts in which they’re found.6 Maybe the screen is also a veil, one that dissolves the boundaries between public and private space. In online spaces we reveal ourselves in strategic ways.

With the help of social-media apps, Indigenous peoples have been able to document themselves in new ways, writing themselves into history because they intuit that to archive themselves gives their existence validity. Natasha adopts the language of online confessionals, paying tribute to these hidden histories that are being recorded online using social media. These platforms have allowed greater democratic participation and representation than ever before. In the past, archives have been carefully curated by institutions and trained professionals as sanctioned by the church, and later the state. Today this practice is continued by GLAM institutions (galleries, libraries, archives and museums) who continue to speak for and define Indigenous peoples using colonial concepts of authenticity. As Wiradjuri archivist and writer Nathan Sentance asks, “archives hold memory, but whose memory?” He writes:

In regards to First Nations cultural heritage, it has been argued that memory institutions are tools of colonisation in which colonial powers used to proliferate narratives for their own means.

Given that archival institutions have always been “[c]reated by state-sanctioned surveillance and violence,” he explains, “these archives have the power to sustain and reproduce that same violence.” Online discourse therefore becomes a powerful tool to reimagine those systems and to go against them. In this context, the dissolving boundary between private and public isn’t seen as a threat, but instead a pathway to empowerment for Indigenous peoples and WOC alike.

The sensuality of fabric, often associated with the figure and interior space, is a far cry from the hardware and mobile networks that characterise the digital era. Natasha’s process expands the notion of textile art as a visual language and social practice. Without ready access to resources, she makes use of what’s most easily available – the internet, spray paint and stencils, ready-made fabric, sometimes a sewing machine, and studio space at her day job. She says, “Some things are sewn and that is a combination of me, my grandmother and whoever loans me their sewing machine”.7 And that spontaneity leads to work.

These techniques are seen as secondary, however; a means to an end for communicating.8 Unlike the age-old idea of women’s handwoven craft circles, whose communal modes of practice help to form a sense of belonging, Natasha works from the realm of online communities to generate her texts. This process, she says, is an artform itself:

it's almost like a performance where I spontaneously come up with the end product but it requires getting into a certain mood to be able to write [the texts], retracing my steps. 9

Natasha uses social media to explore the possibilities of language. Her Instagram posts, for example, function as maquettes or models for larger works. They include online devotion for anti-hero actors like Tom Hiddleston, who plays Loki in the Thor film series, and Cody Fern of the television series American Horror Story. In the work Love letter to the actor Cody Fern, she pieces together popular images and ideas about the TV star that have been widely circulating the internet. Her obsessions border on erotomania, the kind often seen online in the form of ‘stan culture’. However hers go one step further, and border on grotesque in their revealing of the unknown, unspeakable desires of an invisible body.

Natasha’s process falls into the realm of performance art, in its testing of the boundary between reality and fantasy. Online performances more specifically tease out the concept of ‘augmented reality’, a term which describes “the reality of our world in which physical and digital spaces have become irreversibly enmeshed.”10 It’s a practice that’s been popularised in recent years by artists like Amalia Ulman and Frances Stark. Dealing with the gaze of the female flâneur, women’s online performance takes on another dimension. Natasha’s ironic romantic gestures also carry traces of notorious flâneuse Sophie Calle, the French artist who famously stalked a man for 12 days. In her book Exquisite Pain (2004), Sophie recalls events before and after the moment she was dumped by a man over the phone in a foreign hotel room. Throughout the book she reflects on the moment repeatedly and, in doing so, describes herself in relation to her love interest.

Working from a perspective that’s embodied and relational, these artists invite us to contemplate their gaze as they express adoration. This isn’t intended to dehumanise them or cause some sense of identity dissonance. Instead it’s meant to trouble us, the viewer, in our position as onlooker. Seamless participation in one’s fantasy narrative is further enhanced by the internet’s integration into most aspects of daily life. In this reality, objects and ideas often take on a life of their own. Meme culture, for instance, shows us how images are removed from their context and virtually transformed into another message. In doing so they become like living creatures, proliferating independently of their original form.

There’s something innocent about longing. It implies an act of gazing upon the object of your affection from your inadequate position. It’s an act of self-abandonment, in favour of something higher, beyond yourself. In Natasha’s expressions we see many things, including a longing to escape a messy, violent reality; a longing to transcend the body. Her language appears in the gallery, disembodied like a phantom. It overshadows her identity, whose importance recedes into the background as the object of her fantasy bleeds into the foreground.

Two of Natasha’s works from the end of 2019 signal a shift into the dark side of online intimacy. Here she confronts the realities of hyper-consumption, where capitalism has invaded every stretch of our personal, most intimate lives. They reveal more about the artist – and perhaps ourselves – than her previous confessionals. One of these, I Know Everyone’s Miserable But How Does That Help Me (2019), appeared as part of the group show twenty-four-seven at Te Uru Gallery, curated by Ioana Gordon-Smith.

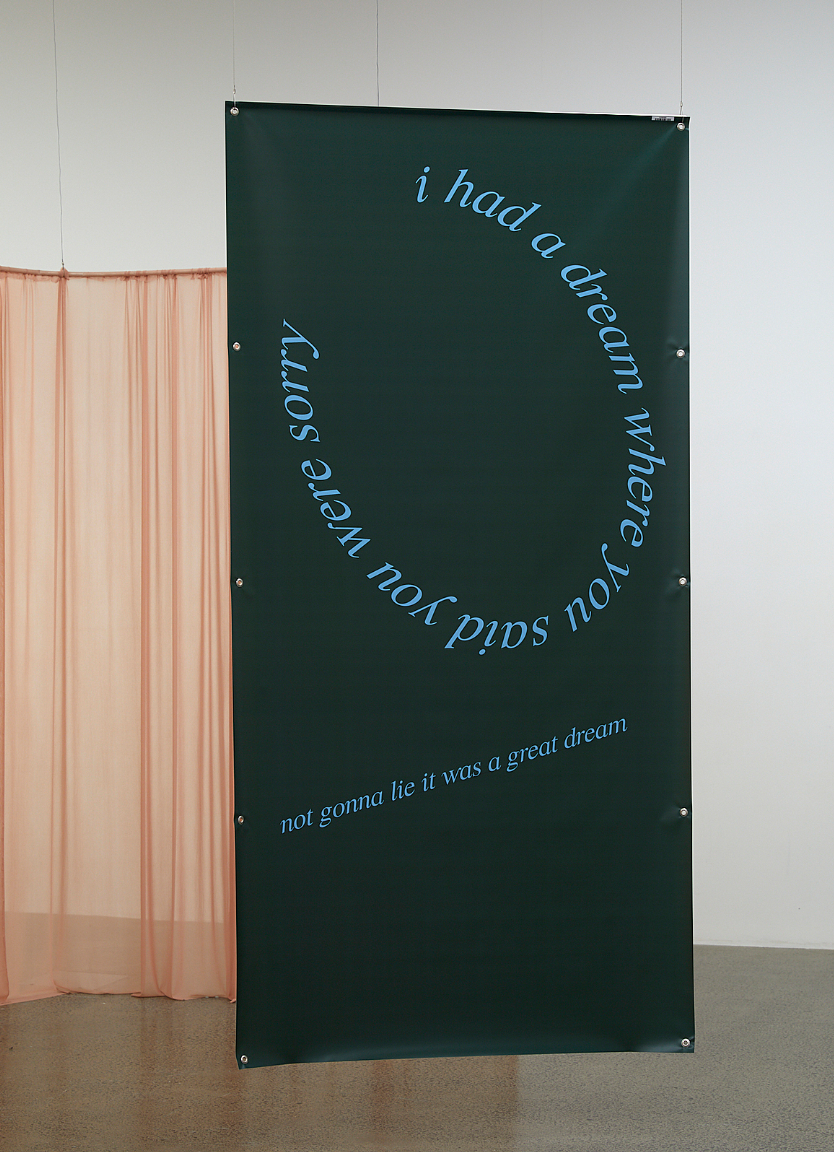

A private zone in the gallery is marked by a sheer pink curtain, cradling the viewer in the artist’s virtual fantasy landscape. Her signature confessionals intersect the space in a Kafkaesque frenzy. This time they’re made from a series of PVC banners, the kind found in shop-window displays. They appear flat, less tactile, but no less mesmerising to look upon. Her texts appear in oblique shapes and unexpected hues, mirroring the multiple gazes made possible by digital interfaces. Cringey, humourous stories of failed attempts at intimacy, a list of Tom Hiddleston Google searches, social anxiety and loneliness, quick-fix food and anti-depressants adorn the clean, pastel surfaces. They seem to suggest that in the search for the flat, the sanitised, the perfect ideology, we also desensitise ourselves from the violence of reality. We cut the bond that links us to one another. In our constant search for universality we promote aesthetic ‘flatness’.

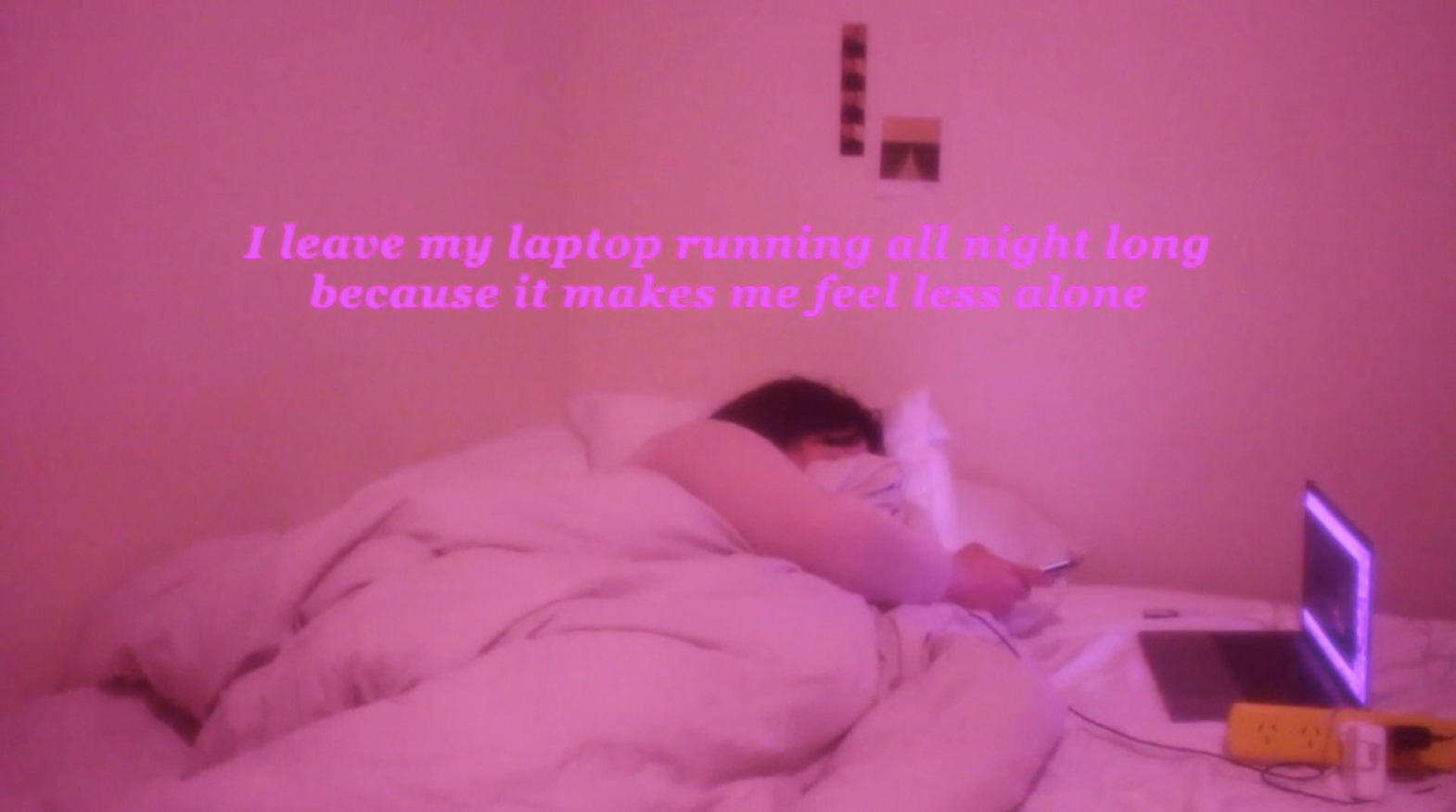

In the second of these two works, and her most recent, a seven-minute video made as part of CIRCUIT Artist Cinema Commissions 2019, we see her confessionals return to the screen. If I die, please delete my Soundcloud (2019) depicts a figure lying in a large white bed next to an open laptop, a partner surrogate. Alone in her personal space, with a multi-socket power board propped up in the foreground. She’s fully immersed in the echo-chamber of her private digital zone. At times she checks her phone, scrolling through the timeline with mild interest. Nothing else exists in the frame except her confessional texts which fade in and out like memes. There’s no past, no future, just an infinite present. This is a world that has no beginning or end, nothing beyond itself except its own potential, the opportunity of something better, always just within reach.

These two works convey a reality where, through everyday advertising and media representation, women of colour are told they’re not valued. This perceived lack of value is internalised, mirrored and amplified within a feedback loop. The idea that our value is seen as a result of our own individual mental effort, a reward for the deserving, promotes the idea that all problems are personal and can be solved by personal responsibility. It’s a framework that benefits the status quo, and removes the possibility of deeper, broader change, or of holding accountable the powerful who benefit from the status quo and its myriad forms of harm.11

The capitalist impulse to privatise our innermost thoughts and emotions is entrenched by the internet’s design. Features like infinite scroll, newsfeed, autoplay, likes and followers, among many others, are designed to keep our attention hooked on an ever-unfolding present. We’re always casting our attention on the present, encouraged to always ‘be in the moment’, with the aim of personal efficiency and a maximisation of physical and mental power. From this vantage point there’s no colonial past, there’s only a colonial present. Colonialism wasn’t a moment in time, it’s still happening.

Institutions choosing to overlook or ignore the nuances that Indigenous people face as a result of colonialism is a conscientious erasure of history. If cloth contains memory, it would be the hours and days on end spent staring into screens, obsessing over celebrities and trending topics. If cloth contains memory, it’s the fragility of colonial systems that seek to erase the past, leaving one completely vulnerable to the present. It would be the ‘flatness’ of relationships that are increasingly mediated by screens, a flatness that’s inseparable from the commodification of relationships online. Despite encouraging collectivity, online spaces are exceedingly private. Curated by algorithms that lock you into a ‘filter bubble’. Interfaces become a surrogate for conventional intimacy, teaching us to fetishise lonesome thought.

Natasha’s last two works of 2019 indicate a sense of ambivalence towards capitalism’s exploitation of our “private thoughts, anxieties and desires for public consumption” online.12 As this decade transitions into the next, we find ourselves in an insatiable online market that’s captivated by raw and unfiltered content, with the potential for virality always on the horizon. Natasha reveals the self as one “caught up in the rhythms, pulsions and patternings of non-human forces.”13 One that’s in a constant state of folding the outside in, aware of its own detached intimacies. This position isn’t supposed to be a cause for alarm or answers, but simply to state its own existence. In doing so she creates space to contemplate herself outside the need for a function. By sharing this gaze she troubles our own gaze, as she continues about exploring her pleasure in online spaces.

1 Lucinda Bennett, “A critical approach to intimacy in art” (Master’s thesis, University of Auckland, 2017), 4.

2 Victoria Wynne-Jones, “Through the skin the world and the body touch,” Le Roy 3 (2015): 32.

3 The artist’s Instagram highlight, titled Questions. Accessed November 2019.

4 Lucinda Bennett, “A critical approach to intimacy in art” (Master’s thesis, University of Auckland, 2017), 5.

5 Reina Lewis, “Foreword,” in Veils: Veiling, representation, and contemporary art, ed. David Bailey and Gilane Tawadros (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press), 14.

6 Ibid.

7 Email correspondence with the artist, November 2019.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

10 Ibid.

11 Stef Aupers and Dick Houtman, “Silicon Valley New Age: The co-constitution of the digital and the sacred,” in Religions of Modernity: Relocating the sacred to the self and the digital (Leiden, NL; Boston, MA: Brill, 2010), 161-185.

12 Wall text, twenty-four-seven, Te Uru Waitakere Contemporary Art Gallery, 2019. Curated by Ioana Gordon-Smith.

13 Mark Fisher, The Weird and Eerie (London, UK: Watkins, 2016).