Travelling Light

Cherie Lacey looks back at the Colin McCahon's Victory Over Death II, and how his work has influenced her own life as well as New Zealand's aesthetic sense.

Footwork

Until recently, I hadn’t thought much about Colin McCahon’s work for many years, and I remember reaching saturation point with it during my 20s. We’d been given McCahon’s work as a model throughout high school art classes, invited to imitate his progression from figurative representation towards abstraction, all the while rehearsing questions of personal identity and cultural nationalism. These debates surfaced again during undergrad art history classes, many times. McCahon was everywhere, and I started to think of his work as too conventional, too established, too boring*.

A few years ago, however, I moved to Melbourne, and in my homesickness and nostalgia, it was the New Zealand depicted by McCahon that came back to me. These images allowed me to sink further into my melancholia and feel myself even more alone, in that self-indulgent way that reminds you that you’ve lost something treasured and hence must once have had something to treasure. In that state of regret, experiencing a loss of faith in the choices that I’d made, these remembered landscapes reminded me that I was a stranger in Melbourne, utterly unconnected to that land and that place.

In my mind, home started to become indistinguishable from these remembered landscapes, and even though I’m not Māori or Christian, McCahon’s vision of place reminded me of who I was at a time when I sensed myself forgetting, as I drifted further away from the person I used to be. I sought refuge in these memories, retreating to them time and again in order to seek some strength, a way of carrying on. This essay is an attempt to make conscious that moment of recognition, to trace the series of associations between memory and land and McCahon, for myself at least, and how these form my understanding, my recognition, of home.

When I first sat down to write, I thought that I was going to write about Pākehā memory in a more general way—a sort of cultural study of Pākehā memory. What came out, though—and this was completely unexpected—was the first-person singular. If this wasn’t enough, it was the most forthright assertion of the first-person singular you can get: the image of I AM claiming the prime real estate of my conscious mind.

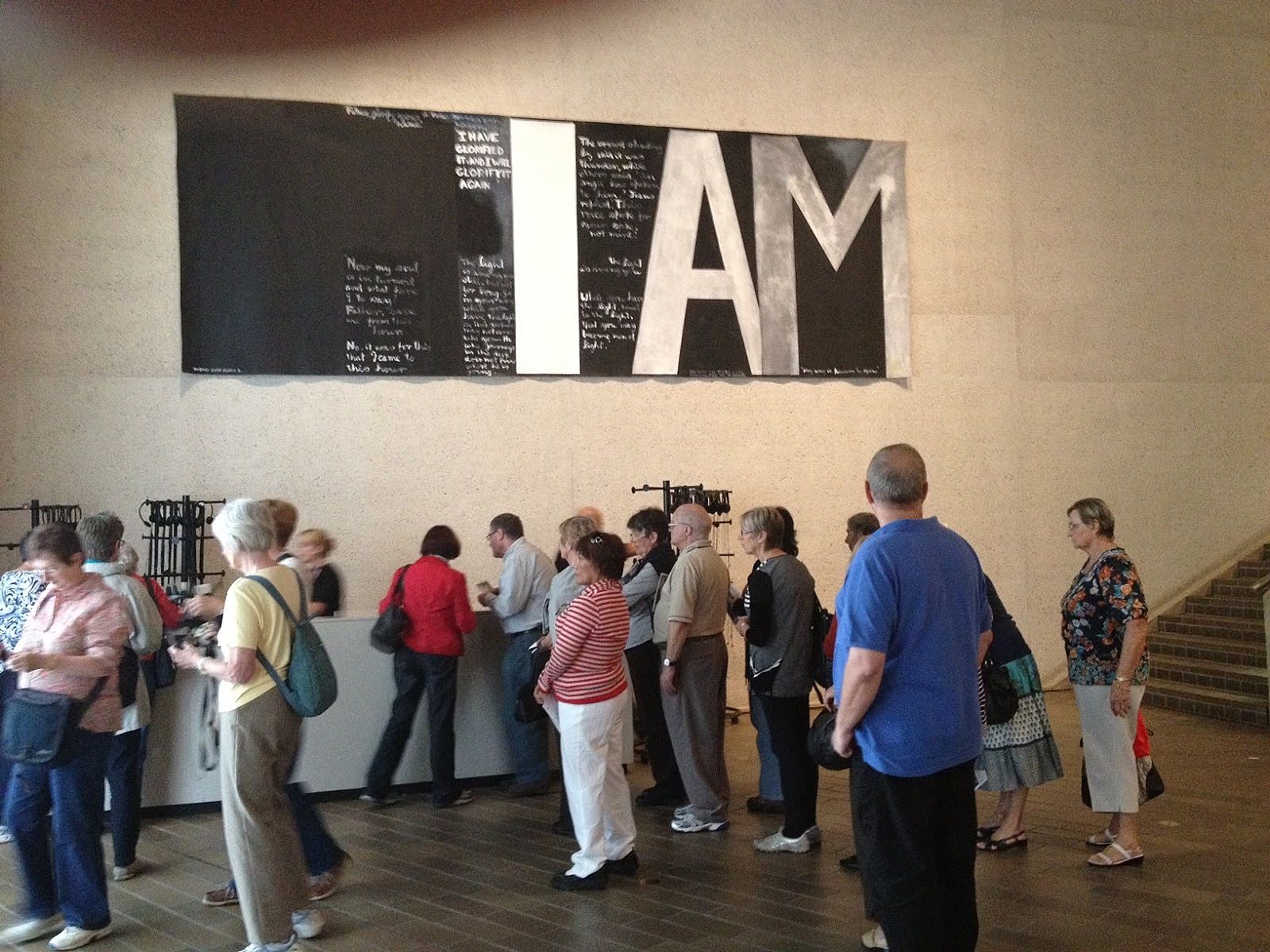

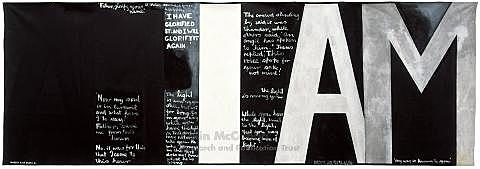

As a teenager I had a small postcard of Colin McCahon’s Victory over Death II (1970) pinned to my bedroom wall. Growing up in a secular household, I didn’t recognise the words as religious, and the cursive script surrounding the words I AM, taken from The New English Bible, was too small for me to read. Instead, I interpreted it as an assertion of identity, a confident declaration of existence, a take-it-or-leave-it attitude to the world. I think it moved me because it felt so different from my own fragile and insecure adolescent identity, which seemed to be constantly searching for the object that would round off those two words: I am this.

Later, when I went to Victoria University to study art history, the lecturer pointed out that the black, velvety space on the left-hand side of the canvas contains two indistinct letters, AM, posing a question against the “I” on which they impact. For the first time I realised that the certainty declared by those two luminous words, I AM, were haunted by doubt. A questioning voice calling out from the darkness: AM I?

The orthodox interpretation of this painting draws parallels between Moses’ Exodus from Egypt and Pākehā settlement, each group leaving home in search of the Promised Land, and the journey from the darkness of human doubt to the presence of the Divine*. The words I Am are spoken by God in the Book of Exodus, who is responding to Moses’ question about how He should be described to His People. ‘Tell them: “I Am; that is who I am”’, God says to Moses.

McCahon has said that his paintings are almost entirely autobiographical, and this work has been read as a testimony to the artist’s own struggle with questions of faith, caught between doubt on one side and belief on the other. It’s often placed alongside his earlier piece, I Am (1954), which appears free of the apprehension that plagues his later work. On close inspection, the smaller text on Victory over Death II contains excerpts from the Bible that describe a soul in turmoil as well as a mounting danger - placed together, the two pieces form part of a larger personal narrative about McCahon’s search for a peace that evaded him until his death. Moses didn’t make it to the Promised Land, and McCahon’s life ended in alcohol-induced dementia, the final words on his final painting reading: endless yet never, no full-stop.

Learning of the academic interpretation didn’t overwrite my earlier impression of the work, however. Instead, the two readings merged. Now when I hear the arguments about New Zealand’s coming of age, my mental image is of my teenage self, standing before McCahon’s painting like some unfortunate, pimpled metonym of settler angst. I identified then, as I do now, with McCahon’s search for faith and certainty—not the religious impulse but the restlessness of spirit, which I have in some measure, and the ongoing battle between the drive that keeps you moving and the desire to be settled. In the later paintings, like Victory over Death II, the anxiety increases as time runs out, the search not yet completed: the light is among you still but not for long, McCahon scrawls across the canvas, as if in haste. These days, the I AM of this work speaks to me not of certainty but rather of a longing for certainty—an ongoing pursuit, as the light remains, to find the object that would finish the sentence. This is the object that would allow me, perhaps McCahon himself, and perhaps even the settler in this land, to be anchored to this place, finding at last a kind of stillness.

These thoughts were resurrected recently as I was carrying out some research on Pākehā settlement and the operations of memory. I was looking for a way of arguing that Pākehā do possess a cultural memory, despite the numerous persuasive claims that we’re an amnesiac culture, prone to forgetting the past. I re-read Stephen Turner’s essay, ‘Settlement as Forgetting’, which—as the title indicates—argues that settlement requires the settler to forget their history as colonisers. Cut off from anything that would ground the settler in a solid relationship to the past, like a radical break with the Old Country or the act of colonisation itself, Pākehā have become a melancholic, forgetful people, condemned to repeat the mistakes of history. I’m condensing here what is a brilliant argument for the sake of hurrying to the point, which is his claim that Pākehā culture lacks an object of memory*.

Turner’s argument recognises the roots of the word forget: ‘for-’ meaning to neglect, or to let slip, and ‘get’ meaning to take hold of an object; so, forgetting is when the object slips from our grasp. It was here, at this point, that I was able to trace my train of thought back to the painting: I AM, which consists of a subject and a verb, but is, like the reputed state of the New Zealand settler, cut off from the object, suspended in an endless present tense.

However, I have never been absolutely convinced by the argument that Pākehā are a forgetful people; this is not a trait that I recognise in myself, nor in our cultural texts. I think that we do have a difficult relationship to the past, particularly our colonial past, and that this difficulty is connected to an anxiety about our status as settlers, or non-indigenous. This is an argument that goes over old ground, but what I detect in it is a certain directionality towards the past; said slightly differently, I think that Pākehā have an intention to remember. If we take this intention in its most literal sense, we can understand it as a stretching out, or as the act of straining, which to me better expresses an effort to remember, rather than remembrance as a completed or accomplished act. Of course, the word intention is used intentionally here—dragging along with it the tradition of phenomenology, referring to the notion that all consciousness is consciousness of something.

Jean-Paul Sartre has said that this ‘something’, this object, can be anything at all, including the expectation of an object*.

According to this tradition, we know ourselves as conscious beings, as capable of saying I am, precisely in this act of stretching out towards the object. Perhaps it is the old associative process at work, but I can’t help but re-interpret the I AM of McCahon’s work as a testimony of this intention, captured in the process of looking for the object, rather than the complete absence of one.

The ancient Greeks distinguished between memory-as-object (memories) and memory-as-intention (the work of memory). I am operating mainly on intuition here, but I suspect that claims about Pākehā forgetfulness are too fixated on memory in its object form, on memories as such. Such an obsession with the object deteriorates sooner or later into the realm of impossible politics—debates over which events should be commemorated, whose memory takes priority, and so on. This is not to deny the importance of such questions, but, to me, it moves too hastily through questions of memory, its particular operations and functions, and finds itself at an impasse.

Nonetheless, I don’t want to discard these questions too quickly, because I see in them, perhaps despite themselves, a desire to remember. Wrapped up as they are in debates about Pākehā belonging and identity, and attached to the object that is the nation, they claim that until we properly remember (whatever that means), we will remain unconnected to this place. This argument, of which I have myself been guilty, begins to look a lot like a course of collective psychotherapy, in which we’re required to bring out all those buried, repressed memories with the aim of making us feel better about being Pākehā. I think we need to slow the course, and concentrate first on questions of how we remember, before we consider the question of what.

Recollection is, in this sense, the action by which one can call up again all the things that have been stored away in memory—literally, re-collecting, or gathering together again, the objects contained in memory’s vault. The end point of this search is marked by the moment of recognition, when you’re made conscious again of the object that you set out to find. However, it’s not always the case that you arrive at this happy moment, and the effort to recall comes with no guarantees: there’s always the chance to you’ll return empty-handed, despite your best intentions.

For me, the action of recollection, as it takes place in writing, is what interests me most. This is not memory understood in its past tense, as already having happened. Nor is it memory as the object (re-)found, nor even guaranteed to be found; failure is the ever-present threat on this particular horizon. Rather, it is memory that emerges only in the conscious act of looking for it, by sheer effort of will—the decision to set off in search of a memory and the paths that I choose to take. Paul Ricoeur has commented that recollection is arduous work at the best of times*, but in this country of deep mud and steep cliffs, this kind of movement isn’t always easy or simple.

Landscape (interior)

McCahon claimed to have had a religious vision as a teenager while on a family drive through the South Otago hills. Years later, in 1966, he recalled the experience:

Driving one day with the family over the hills from Brighton or Taieri Mouth to the Taeri Plain, I first became aware of my own particular God, perhaps an Egyptian God, but standing far from the sun of Egypt in the Otago cold. Big hills stood in front of little hills, which rose up distantly across the plain from the flat land: there was a landscape of splendour, order and peace*.

According to his son William, the hills he was looking at, which mark out the inland boundary of the Taieri Plain, were called Maungātua (Mountain of the Gods) by the Māori. William says that his father —

had seen God within his own landscape—a landscape he called home. He saw the land anthropomorphically as God, the hills and valley reflecting a force that, contained within them, was struggling to emerge; a force he had now experienced. ‘I love the land; the land loves me back,’ he would say*. (Emphasis mine)

Gordon H. Brown, an art historian and one of McCahon’s close friends, has connected McCahon’s teenage vision to the artist’s life-long attempt to communicate a divine force within the New Zealand landscape. McCahon felt himself tasked with summoning this force, to reveal the hidden meaning of things. In one of his early mission statements, McCahon tried to account for this by saying that he “saw something logical, orderly and beautiful belonging to the land and not yet its people. Not yet understood or communicated, not even really yet invented. My work has largely been to communicate this vision and to invent the way to see it.”*

This mission has been more successful than I think even McCahon himself would have dared to predict. Like myself, numerous people have commented on the way that McCahon invented a way of seeing New Zealand. Martin Edmond, for example, in his book Dark Night: Walking with McCahon, describes a trip back to his hometown of Ohakune like this:

[D]riving up Dreadnought Road to the Junction to have dinner at the Powderhorn, near the corner of Soldiers Road we saw in the sky ahead the ochre light, swirled with black, that is the precise shade McCahon uses again and again in his Truth from the King Country series. It was the sun setting in the west behind Hauhangatahi, the last orange light flaring across Tohunga Junction; and beyond over the dissected, bush-covered hill country of the upper Manga-nui-a-te-ao and the Whanganui. When a man in Hawke’s Bay, Sylvia Ashton-Warner’s son, said McCahon taught us how to see New Zealand landscapes, I thought: Yes…. But… Now, suddenly, here was something that I simply would not have seen in the same way had I not looked at those paintings*.

This is how Dame Jenny Gibbs, art collector and philanthropist, explains it:

When I drive through New Zealand, what I see is a land full of Colin McCahons. I mean Colin McCahon taught me to see the land here, I think he has that sort of significance; he made us aware of the difference that this land has from, say, Australia or Europe or anywhere else. He made us aware of our isolation, our seeking of an identity, our nationalism, I mean he was a tortured soul but in many ways he epitomises that sort of dark spirit of New Zealand that you see in our films*.

As Gibbs points out, many New Zealand films have referenced the landscapes of McCahon, which have become a sort of cinematic short-hand for our (white and neurotic, as Merata Mita said*) cinema of unease. In his personal documentary that coined this term*,

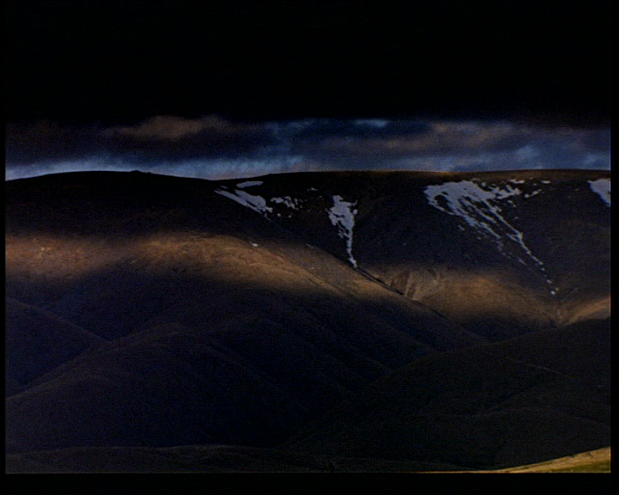

Sam Neill’s narrative begins: “I’m an expatriate. Like all those who are separated from their country, I dream of home. I dream of New Zealand.” As the scene shifts from a busy London street to landscape shots of New Zealand, he continues:

This is what I imagine when I’m away—this lonely place. Why this particular spot? Possibly because of its magical silence, its haunting emptiness. I’ve been up and down this road many times before and never seen, never heard another car, another living soul. Or, perhaps it might be that, now that we’ve produced a national cinema in this country in the last 15 years or so, I now have a permit to dream cinematic images that are of our own place. And this is my place.

To illustrate what Sam Neill dreams of when he dreams of home, the camera pans slowly along a line of mountains—dark land, a strip of light on the horizon, ochre foothills—unmistakably, self-consciously assuming the complanate appearance of a McCahon canvas, circa mid-sixties.

This feels similar to the landscape that you see in Heavenly Creatures (dir. Peter Jackson, 1994), for example, when Juliet flees in anger from her parents’ crib and into the Port Hills, disappearing from view. Pauline runs after her and the camera follows as it broadens to an aerial shot, frantically scanning the landscape as if it has joined in the search. The images recall one of McCahon’s peninsula landscapes, or perhaps his later, more distilled abstract landscapes, where big hills stand in front of little hills, one after another rising up to meet the horizon. Shot from above and accompanied by a rousing operatic soundtrack, the scene borders on a religious experience, which is, of course, precisely what happens in the following scene. Or, we might think of those West Coast hills in the opening shots of Bad Blood (dir. Mike Newell, 1981), where the camera moves along a mountain range shadowed by the threat of rain, its ridgeline traced by the last line of light.

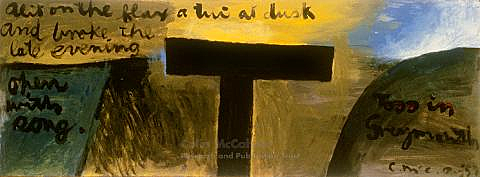

This is the same landscape that McCahon depicted in his Toss in Greymouth (1959), where the rain-heavy clouds climb over the hills, turning the light sepia. In Bad Blood, too, the camera enters the landscape in search for someone who has gone missing. This time, we’re looking for Stan Graham, the troubled man-alone type who disappears into those very hills, which prove reluctant to give up their secret.

Colin McCahon gets a more explicit mention in the opening sequence of Crush (dir. Alison McClean, 1992), as the two main characters drive through a deserted central North Island landscape, the Urewera ranges as their backdrop. “McCahon said that ‘it’s a land with too few lovers’”, one of them quotes, just before they swerve off the road and crash into a paddock. In The Piano, it’s McCahon’s beloved West Coast beaches that are featured, as a detained Ada travels in memory, over the “cold and dripping” bush*, back to the stretch of black sand at Karekare, scanning the coastline for her abandoned piano.

Although all of these landscapes recall McCaon’s in their physical appearance, reiterating the notion that McCahon invented a way for us to see the land, there’s something else at work in these connections. Each one charts a journey or movement, a shift from one place to another. In McCahon’s own description, he recalls that his first vision took place while the family were driving through the hills, the young McCahon staring out the car window at the passing landscape. This is repeated in various ways in both Edmond and Gibbs’ descriptions, where a car journey provides the opportunity to reflect on notions of place and home, as revealed by, and mediated through, McCahon. Sam Neill’s central motif is the road, which he relates to the persistent theme in New Zealand/Pākehā cinema of the journey.

Crush is open about its connection between the road trip and McCahon’s landscapes, while Heavenly Creatures, The Piano and Bad Blood reveal the land as a keeper of secrets or other objects, mobilising characters in a search to uncover or recover them. In these visions of New Zealand, the land is not still or settled. Rather, it is revealed precisely in the act of moving through it; or, you could say that it takes shape only in movement. This is getting close to another vision of McCahon’s, a later one, where he said that he wanted to “make paintings to walk past” in order to involve the viewer in a physical act as part of the viewing process*. For McCahon, and others who have followed in his footsteps, it seems that the land reveals itself only in passing.

These moving landscapes remind me of McCahon’s fascination with geomorphology, which is “the study of the forces in operation that go into creating the surface of the land”*.

McCahon was given Charles Cotton’s book The Geomorphology of New Zealand as a wedding present in 1942, which conveyed the underlying structures of the land, how it was formed. McCahon has said of Cotton’s work that he “loved his drawings for the way they told about things” and, from that moment on, he “constantly referred to Cotton to explain what it is that I’ve actually seen”*. In his introduction, Cotton explains that, usually, the land is formed not by a sudden catastrophic or miraculous event; rather, it is the result of ongoing processes of formation, the action of forces still in operation. Over time, he says, the land experiences a sort of “wearing away”, “wearing down”, or “etching out”, and we can interpret the landform through the surface appearance of these underlying actions*.

For me, McCahon’s landscapes can be read as an attempt to summon up these hidden forces, forces both geological and not of this earth, which go into forming the outward appearance of the land. Even in his later works, the ones that consist entirely of words or numbers and black space, I see landscapes, entirely interior, as though made up only of the things he has called forth, or summoned up, from beneath the surface.

McCahon said that he always painted his landscapes from memory, and often sought in this experience a way of escaping the present, trying to summon an earlier moment in time—these are “just bits of a place I love”, he said one, “painted in memory”*. Following McCahon, I’ve come to know New Zealand not as an object that I can easily grasp, nor something that I can possess. Rather, my own New Zealand becomes inscribed in the very act of searching for it. My relationship to home is always a remembered relationship to home, a location to which I keep returning in the manner of a journey.

This search doesn’t take place outside the visions of New Zealand that come to us through McCahon’s canvases, or those that follow in his footsteps. But it is these very representations, these texts that consciously attempt to grasp the notion of home, that start to give shape to Pākehā memory. Cotton said that the land is not formed by a sudden, miraculous event. Similarly, I don’t think that there is one significant object for Pākehā to remember, which, uncovered, would give surface form to our present Pākehā identity. Rather, memory might better be thought of as something that builds up slowly, over time—an ongoing process by which we start to carve out an image of New Zealand for ourselves. This might be how Pākehā can come to relate to the land here, a relationship to place that takes form through the active search for it and not, I hope, an attempt to take possession of it. It might be a way of recognising an image of New Zealand that has taken hold in memory, and, in this moment of recognition, of familiarity, experience a feeling of being at home here.

Perhaps, then, for Pākehā, it is not so much what we remember when we think of home, which would be New Zealand as a knowable object, easily called to mind. Rather, it might be the drive to remember it that matters, the intention to forge memories of a place, through which we might start to find a deeper or more connected relationship to it—the sense that we have a longer history here, or a more reliable sense of identity.

In re-tracing the footsteps of McCahon (and I think we could name other ‘Pākehā prophets’ here as well, should we go looking for them), we’re not only helping to forge a shared memory of this place, but we start to access and articulate our own, personal history with New Zealand. What has become apparent to me is that, in retracing McCahon’s steps, I’ve opened the door to my own memories, his images returning me to moments from my own past. Perhaps this is a way of building bridges (another of McCahon’s obsessions) between the collective and the personal, so that in remembering a shared image of New Zealand, one is also remembering oneself. In this way, it might be possible for us to begin to understand how a collective, cultural memory—for Pākehā—can address the question of who we are, and, alongside this, at a more personal level, of who I am.

Necessary protection

I visited McCahon’s Victory over Death II when I was in Canberra for a conference a couple of years ago. I was living in Melbourne the time, the city that is growing at a pace unmatched by any other. Here, the warm air gets shut in by the buildings and, even though you know, technically, that you’re near a large bay, the water feels very far away. In my imagination, it was to the beaches of Auckland’s West Coast—Piha, Karekare, Muriwai, Te Henga (Bethells Beach)—that I returned.

I would picture myself walking along the black shore under darkening skies. I could easily see the light that catches the wet sand and turns it silver, the dense bush growing all the way down to the dunes. It was a landscape that was different in every way to the tinder-dry plains of Victoria, and I missed it terribly. When I stood in front of McCahon’s Victory over Death II that day in the National Gallery of Australia, I felt the pull of home immediately. McCahon’s limited colour palette, his self-confessed “joy” at “taking a brush of white paint and curving through the darkness with a line of white”*, shone to me with the particular light out West. I thought of McCahon in his Titirangi studio, trying to summon his god in the landscape, a landscape that moved me more than any other place I’d known. It was at that moment, looking at the great I AM stranded over there in Australia, that I was able to summon up a couple more words to add to the existing ones: I am going home.

Recollection means to gather together again, to literally re-collect objects of memory. However, it can also mean to summon up, and well as to re-trace one’s steps. In all of these processes, memories are able to surface, to become conscious once again, much like geomorphology itself. This is hard work, and I have found the process of gathering some of these ideas into written form harder than I expected. This was particularly the case after realising that I couldn’t avoid writing about myself, to some extent, which is difficult for someone trained in traditional academic scholarship.

Travelling home at the end of a day of writing, after trying to negotiate the space between the personal and the cultural, I would often be struck with a strong sense of doubt, questioning the form that these ideas were taking. The following day, often embarrassed by the personal things revealed here, I would cut paragraphs, whole sections, trying to draw it back into a more academic shape. I produced two parallel texts: cutting and pasting my personal memories into a separate document, and keeping the more academic material in another. In this, I realised at one point, I’d unwittingly enacted the traditional, paralysing dilemma: is memory primarily personal or collective?*

The only way through, I decided rightly or wrongly, was to offer up something of myself, to involve myself in the act of recollection. Just as I tried to suspend the notion of what we remember (or at least tried not to secure an object in this place), I tried not to declare too assuredly the subject of memory, the question ofwho is remembering. Once such a declaration is made, I think that the whole idea of a collective, cultural memory starts to operate solely as an analogous concept: Pākehā memory in general as the extrapolation of one Pākehā’s memories. I certainly cannot claim to have resolved this dilemma, but what I’ve tried to suggest is an equivalency between these two forms of memory, the co-existence within the same frame and the way they impact each other.

The final sense of the word recollection is to recover (mentally), or to become composed again. And so this is, in the end, also a narrative of recovery. I know that a lot of people have an easier time of it, living away from New Zealand. Short visits back home, or even those moments of recollection, can be enough to remind people of New Zealand, before they continue with their expatriate lives. Some people I know move away precisely in order to forget their origins, New Zealand becoming subject to a wilful forgetting. For me, though, the experience was a lot darker, and I suffered without the necessary protection of home.

When I left for Melbourne I was looking for something I thought I couldn’t find here, and, quite unexpectedly, I did find it, although it wasn’t quite the same object I sought in the beginning. What I found was a memory of New Zealand, in which, especially in those moments of darkness, I recognised a place I knew as home. As it turned out, the distance from New Zealand helped to crystallise it in my memory; I still might not know what it was, but I do know which direction I should look in, which is not somewhere north-west of the Tasman Sea.