Two American Cartoonists In The Workplace

When I was much younger, I would eagerly devour the comic strip anthologies I found in second-hand book stores or public libraries. I would hustle and save pocket money, guffaw in the privacy of my little bedroom, try to replicate the characters on tracing paper, try and create my own. None of this was especially distinguished or selective, because lonely 8-year old boys consume their cartoons much the same way lonely 28-year old men consume their pornography - omnivorous, voracious, and none too picky. I’ve kept quite a lot of my hoardings. I still have beloved and dogeared trade paperbacks of Peanuts, The Far Side, and (my personal favourite) Calvin & Hobbes. I also have a couple of Dilbert books.

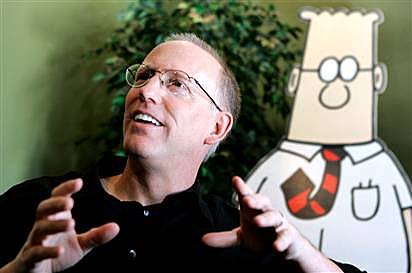

Dilbert, for those not in the know, is the product of white-collar refugee and sometime-blogger Scott Adams. The strip revolves around the office job of an engineer named Dilbert and the idiosyncrasies of management in a large company. Someone at Wikipedia with a penchant for lists broke its themes down in painstaking detail, including:

- Scheduling and budgeting without reference to reality

- Failure to reward success or penalize laziness

- ISO audits

- Budgeting, accounting, payroll and financial advisors

- The bizarre habits and failure to understand capitalism of underdeveloped countries

And so on. When I started manifesting a couple of critical faculties as an adult (wee, vestigial things, like prehensile antennae), it became clear that there were differences in the strips I read - in terms of the ideology being presented, the demographic they aimed for, the aesthetic quality of the art itself. It became a lot clearer how these varied. It’s also interesting delving into the biography of the creators and tracing that back to what they eventually published - Charles Schulz’s battle with doubt and depression throughout his creative lifetime, the influence of Gary Larson’s beloved older brother (his tall tales, his lay science) on The Far Side’s mad, thoroughly askew, and endlessly entertaining anthropology.

I think it’s telling to compare two pieces of writing, one by Adams and one by Calvin & Hobbes creator Bill Watterson, which I came across last week - each about a certain group, though for different audiences (this is telling too, because the audience you feel most comfortable addressing and persuading says more than a little about yourself). On April 9, he penned a piece for the Wall Street Journal: ‘How To Get A Real Education’:

“I understand why the top students in America study physics, chemistry, calculus and classic literature. The kids in this brainy group are the future professors, scientists, thinkers and engineers who will propel civilization forward. But why do we make B students sit through these same classes? That’s like trying to train your cat to do your taxes—a waste of time and money. Wouldn’t it make more sense to teach B students something useful, like entrepreneurship?

….

There was a small business on our campus called The Coffee House. It served beer and snacks, and featured live entertainment. It was managed by students, and it was a money-losing mess, subsidized by the college. I thought I could make a difference, so I applied for an opening as the so-called Minister of Finance. I landed the job, thanks to my impressive interviewing skills, my can-do attitude and the fact that everyone else in the solar system had more interesting plans.

The drinking age in those days was 18, and the entire compensation package for the managers of The Coffee House was free beer. That goes a long way toward explaining why the accounting system consisted of seven students trying to remember where all the money went. I thought we could do better. So I proposed to my accounting professor that for three course credits I would build and operate a proper accounting system for the business. And so I did. It was a great experience. Meanwhile, some of my peers were taking courses in art history so they’d be prepared to remember what art looked like just in case anyone asked.”

You’re so right, Scott. Studying science is stupid.

What ensues is a long and anecdotal list of Adams’ ‘life lessons’ - Steve Jobs and Warren Buffett taught him to communicate with maximum effect in his strips; Adams ‘created value’ in Dilbert by synergising art talent, writing skills, a sense of humour and business knowledge. Having demystified his work so clinically, he ends up saying it’s imperative these are all taught somehow, in addition to necessary miscellaneous finance and management papers. The question of what the young people studying would themselves like to do, and how - be they A students, be they B students - is not addressed.

Famously private, Watterson also talked about higher education on one notable occasion when specially invited by his own alma materto do so at a commencement address in May 1990.

“Having an enviable career is one thing, and being a happy person is another.

Creating a life that reflects your values and satisfies your soul is a rare achievement. In a culture that relentlessly promotes avarice and excess as the good life, a person happy doing his own work is usually considered an eccentric, if not a subversive. Ambition is only understood if it’s to rise to the top of some imaginary ladder of success. Someone who takes an undemanding job because it affords him the time to pursue other interests and activities is considered a flake. A person who abandons a career in order to stay home and raise children is considered not to be living up to his potential-as if a job title and salary are the sole measure of human worth.

You’ll be told in a hundred ways, some subtle and some not, to keep climbing, and never be satisfied with where you are, who you are, and what you’re doing. There are a million ways to sell yourself out, and I guarantee you’ll hear about them.”

The entire speech is absolutely worth reading - and re-reading.

As of 2011, Watterson has retired from commercial writing and drawing. His refusal to license merchandise from his creation means he continues to receive royalties from sales of his compiled strips, but sees none of the other cream most of his comparably successful peers also adduce in t-shirt, coffee mug, and air freshener sales. He lives in Chagrin Falls, Ohio, where he paints, fishes and will occasionally write pieces in newspapers on topics other than himself (in fact, he wrote for the WSJ too, in 2007, reviewing a biography of Charles Schulz - this seems to reflect an implicit understanding of where Peanuts and Calvin & Hobbes now sit astride the canon of American comic art).

Shortly after publishing his piece, Adams confessed to masquerading as a user called “PlannedChaos” on MetaFilter. PlannedChaos had valiantly defended Adams against criticisms of ‘How To Get A Real Education’ - citing his ‘genius IQ’, his ‘enormous success at self-promotion’, and that suggesting that perhaps critics were ‘jealous and angry’. Upon his identity being revealed, Adams apologised for ‘peeing in (MetaFilter’s) cesspool’. Dilbert appears in 2000 papers worldwide, in 65 countries and 25 languages.