Two Utopias

Gareth Shute on two deceptively different futures we're faced with

At all corners, we are inundated with the ‘internet of things’. Occasionally, in between, we catch glimpses of a more sober utopia presented by environmentalists. Whose dream of the future should we aim for, asks Gareth Shute?

Earlier this year, I was at a web conference in Wellington, where speaker after speaker presented glimpses of what they believed lay ahead for the human race. A number of talks expounded on the phrase of the moment – ‘the internet of things’. Originally coined by British tech entrepreneur Kevin Ashton in 1999, the concept envisages all the objects in our everyday lives – our homes, our appliances, our power grids, our vehicles, our public spaces – becoming internet-connected so that they can adjust to the owner or occupier’s whims.

During the afternoon tea break, we drank craft beer that was specially brewed for the conference, then crammed the empty cans into shin-high cylindrical metal rubbish bins that were already overflowing. Where they didn’t litter the carpet, the cans rested atop the leftover food, glass juice bottles, disposable coffee cups and other crumpled wads of packaging from our day of gorging on sponsored snacks and beverages.

There was something jarring about seeing those piles of uncrushed cans – I’d recently read an article explaining that aluminium was one of the best materials to recycle, since it loses none of its properties or quality during the process and uses 95% less energy to recycle the metal than to create it from scratch. Yet here we were – emissaries for the future – casting hundreds of aluminum cans in the bin, destined to be buried along with myriad other items in sports field-sized pits at the edge of town. Environmental scientists and activists alike are now ringing the alarm about climate change constantly (see Carys Goodwin’s piece for this site about how it preoccupies the thoughts of those in the sector) – but at the conference, it didn’t seem to play into the future envisaged by the tech-as-saviour proponents.

It isn’t just a small matter of details – the mindset of the ‘internet of things’ seems to be drawn from an entirely different wellspring of the imagination than even the most idealistic of the environmentalist visions of the future. In essence, we are all being sold two distinctly different utopias, but which is more desirable and is either even possible?

The Internet of Things

It’s September 2026. Your car is driving you home on autopilot while you catch up with the day’s news on the dashboard monitor. Autonomously, the vehicle checks in on local traffic reports to make sure you take the fastest route home. You take a moment to turn on your heating system at home via an app on your smartphone. Your car pulls up outside your house – you set it to park itself in the garage, climb out, and head up the path to the front door. The house has already detected your cellphone, and has turned on lights in the hallway, lounge and kitchen (though it won’t change the settings in rooms that are occupied).

Though the aesthetic is more Pantone Serenity than Pop Art, we’re being peddled a picture from the Golden Age of sci-fi, a modern version of The Jetsons.

The security system has also detected your phone and unlocked the front door for you. On the front step is a delivery of groceries, which your fridge has taken the liberty of ordering. The most fanciful prediction would also have these items delivered by drone – an option you’ll already be able to enjoy, if you like eating a steady diet of Dominoes and taking PR hype at face value, starting this year.

This is the vision of the internet of things at its most domestic and mundane. All of your everyday objects connected, controlled from a distance and automatically adapting to changing circumstances. On the surface, it makes a certain amount of sense – the internet has become an essential part of people’s social lives (due to Facebook and Twitter), their group activities (via online gaming), the way they shop, and the way they gather their news or entertain themselves. Why wouldn’t it extend into the tangible world they interact with as well?

Yet it’s a fairly humdrum view of the future, given that most of the changes to our everyday lives would be so minor – mostly just time-saving tweaks or adjustments to add more comfort to one’s day. Looking further ahead, the internet of things is one where every item in your house will react to your needs instantly – at a molecular level, the oven will know how long the food you’ve put in it needs to cook; the countertop will warm or cool depending on the kind of beverage you’ve just placed on it; and the door will only unlock after recognising your distinctive heartbeat (and I’m not making this shit up).

Though the aesthetic is more Pantone Serenity than Pop Art, we’re being peddled a picture from the Golden Age of sci-fi, a modern version of The Jetsons – the conventional suburban family, except with futuristic household items thrown into the mix so the dad could fly his car to work, the kids could watch TV on their wristwatches, and all the housework could be done by a robot maid rather than paid labour. They even screen-phone each other using a television screen or wristwatch – though it’s ironic that having raced to add that technology to our phones and computers already, we hardly ever use it (apart from awkward interactions with family and friends overseas, looking anywhere but ahead).

Of course, they also thought all our jobs would be done by robots and we’d just swan around doing the important work of entertaining ourselves. George Jetson seems to be paid for switching a computer on and off each day, a state of conditioned uselessness to which people who have worked in certain offices may be able to relate.

Mostly, however, the robots that have taken jobs on assembly lines and self-service counters have increased the dole queues, rather than giving us all more recreation time. The forty-hour work week is still standard, and those who can’t find forty hours’ worth have to balance casual shifts on one hand and WINZ disclosures on the other.

It probably says something about the human psyche that our desire for novelty in our future lives is always balanced out with a desire for the familiar – also an explanation for sitcoms, given that virtually all the successful ones hew tight to the same set-up and only alter a few variables to make a plot from week to week. Our most successful predictions for the future often seem similarly constrained – take our everyday lives and insert a few time-saving devices on top of the existing stability.

But whose everyday lives are we actually talking about here? The digital utopia described above is mainly composed of benefits for homeowners – I doubt many landlords would bother installing internet connected lights, security, and heating for their tenants, given that rentals are already at a premium. Young people in Auckland, Melbourne, Sydney, Vancouver and countless other cities will not be enjoy the soft and comfortable end of an internet-connected physical environment.

In fact, for the more comfortable end of things, companies are already trying to market their best imitation of 2026 . SmartThings (“a lamp that can tell her its bedtime!”) allows your appliances to respond and communicate to you (the door not only unlocks, but also glows a certain colour when the dog has been already been walked), while Hive (“say goodbye to your light switch!”) allows you to use your phone to control the lights and heating in your home.

Other products are more about controlling your own routine – the Fitbit counts your footsteps (“To empower and inspire you to live a healthier, more active life”), Garmin smart bathroom scales record your weight online, and Glowcap pill containers remind you when to take your next dose. The explosion of increasingly bizarre devices can be tracked via the Internet of Shit twitter account, though the man behind it now admits that he often can’t even perceive the purpose of many of these devices and fears that they may one day switch to a subscription model (so you have to pay each month or risk being locked out of your home heating controller).

Most of the items mention above are basically toys for the rich, but you could argue some sort of practicality to them. The same can’t be said for the new internet-connected peg Omo recently released in Australia ("Peggy“). Breathlessly, its press explains how detects the weather outside and consults meteorological forecasts, before sending you a message if it thinks your clothes are going to get rained on. Tech moves fast, so I guess it’s too clunky to go looking up the weather forecast online or – god forbid – just look out the window.

Those who do take up all these internet connected gadgets will essentially live in a hermetically sealed and perfectly adjustable world of convenience. They will be secure in the knowledge that all their household items can transmit their location, thereby making them very difficult to steal. The downside of all that interconnectivity does mean that one’s movements are more trackable than ever – every time you open the fridge, there will be a new data point stored online. Health insurance companies will no doubt be interested in knowing how much you’ve been exercising, taking your medicine or gaining weight. You’d better hope the data is secure and not being on-sold to them (this will be especially relevant in the US, where insurance forms the bedrock of their healthcare system, and where data brokers sell perabytes of private material that could be triangulated to an individual consumer then passed on to private businesses). The likelihood of privacy isn’t great, when even a vibrator company thinks it’s fine to set up their device to report back whenever it is used.

The internet of things is a consumer impulse, rather than a Green New Deal.

Of course, the ease of connectivity also means that more overt surveillance is easier than ever to carry out, so no doubt there’ll be more cameras in urban centres, providing a constant feed to private security or local police station. Your comfort with all of this will depend upon how much you trust your government and police force not to dig into your data, though the knowledge of how what the NSA did with the phone records of US citizens should give us pause (the CIA and private companies alike have both been investing heavily into start-ups that focus on analysing “big data” sets of this kind) as should the NZ government’s clumsy and belligerent passage and enforcement of its own security bureau laws. It may well be that there are two levels of the internet of things – one that provides extra comforts for the top tier of society and another that creates more controls over the lives of everyone else.

The question is: if we decide we don’t like this future, what do we set our sights on instead? The green movement has its own vision of a future utopia, though it sure won’t be much like The Jetsons.Dreams of Green Utopia

As late as the 1960s, the idea of a green utopia remained backward-looking and faintly bucolic in its idealism, with a stiff rejection of the urban and a faintly Luddite approach to new technology. It revolved primarily around a return to farming the land, but using sustainable techniques. You’ll still find plenty of hippies living out this dream in communes around Golden Bay.

However, most modern environmentalists have now realised that there are simply too many people on the planet for each person to have their own block of land to grow food. If all the apartment dwellers in Auckland suddenly got lifestyle blocks – let alone functional spaces to till and farm – the outer suburbs would sprawl all the way from Warkworth down to Hamilton. Instead the modern environmentalist has to formulate a future that acknowledges the need for intensification.

To imagine the green utopia (year indeterminate, and subject to a bevy of public works), you have to start by picturing yourselves on mass transit instead of your private AI chariot. You arrive home via light rail, and find it’s actually pretty convenient – the trains run regularly, and drop you a short distance from your front door, part of the new developments that have sprung up around an expanded rail corridor. The short walk to your house gives your cellphone time to recharge from the kinetic jostle of your pocket as you walk.

Whether you’re a renter or a homeowner, the same minimum standards apply to your home to ensure it is well insulated and doesn’t leak heat (etc). In your absence, the house has turned off the hot water cylinder for a few hours and sold power back to the grid from the solar panels on your roof. This may all seem to return us to the internet of things, but note the subtle shift – instead of your house adjusting to your needs, it is adjusting to society’s needs. The only ‘smart’ thing about the appliances in your futuristic green home is how little power they use – and they certainly won’t waste any by being connected to the internet (the drain on the local power grid is one thing, but internet data centres are almost as power-hungry).

A standard green (or greenwashed) argument in favour of internet connectivity across our daily lives is that it reduces the amount of physical items that society needs to produce – paper is replaced by online reading; our phone takes the place of a watch and a remote control and a calculator, etc. – but the internet of things is a consumer impulse rather than a Green New Deal. It reverses this trend by re-introducing more gadgets back into the world: re-imagined watches that track your movements, new screens for every appliance, and ambient globes that vary colour to inform us of changes in the world at a glance.

In contrast, the real revolution in a green utopia would be an invisible one, streamlining our domestic environments and removing any inessential gadgets. All the power in your home would come from renewable sources, the food in your cupboard grown according to exacting sustainable regulations.

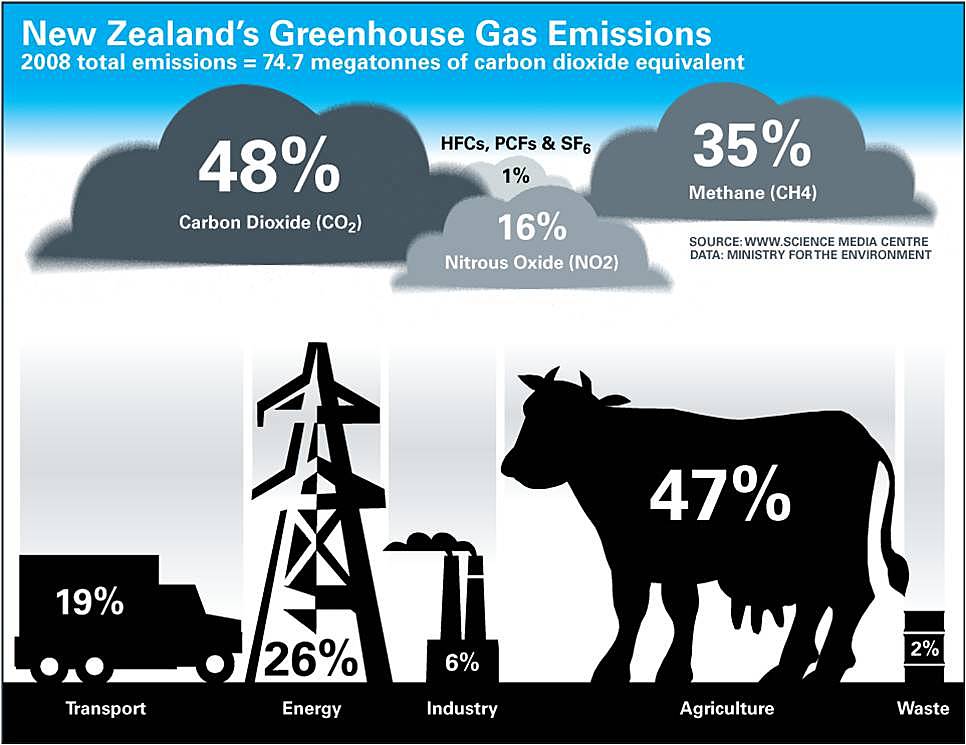

Oh, and did I mention that you’re now a vegetarian? It’s about the only way that this green utopia is going to be possible, unless we all start eating insects or laboratory grown meat. This is the elephant in the room for any fundamental green change in New Zealand, since a real move toward green principles (as opposed to mere tinkering) would mean closing down the beef industry, and probably the dairy industry too. Improvements made by altering stock feed or managing generic codes obscure the fact that there still doesn’t seem to be any scientific way around it: the cows just produce too much methane.

Both these portraits are designed to be broad and everyday. Yet if we compare the green utopia to the house proud ‘internet of things’, it becomes clear even on the big picture that the former is fundamentally a socialist vision – in that it relies on society pooling its resources to create comprehensive public transport system, managing utilities in a way that prizes public and environmental good over dividends, planned changes to the economy that could not happen in our lifetimes as market self-corrections. The most challenging aspect of this (tellingly, one that even modern Green Parties tread carefully around) is that many people will be required to live slightly less comfortable lives, facing some restriction of individual choice so that society as a whole is run in a truly sustainable manner.

In contrast, the idea of an ‘internet of things’ is consumerist at its heart, but also awfully directionless. Our everyday life is improved by novelty products that do fun and time-saving things that mean we can drift through our days without having to worry about anything so tiresome as having to turn on a light switch. This is, of course, why the technological picture is so much more appealing. The short-term gratification of gadgets will always beat the hurdles and disruptions and sacrifice involved in getting sustainable infrastructure.

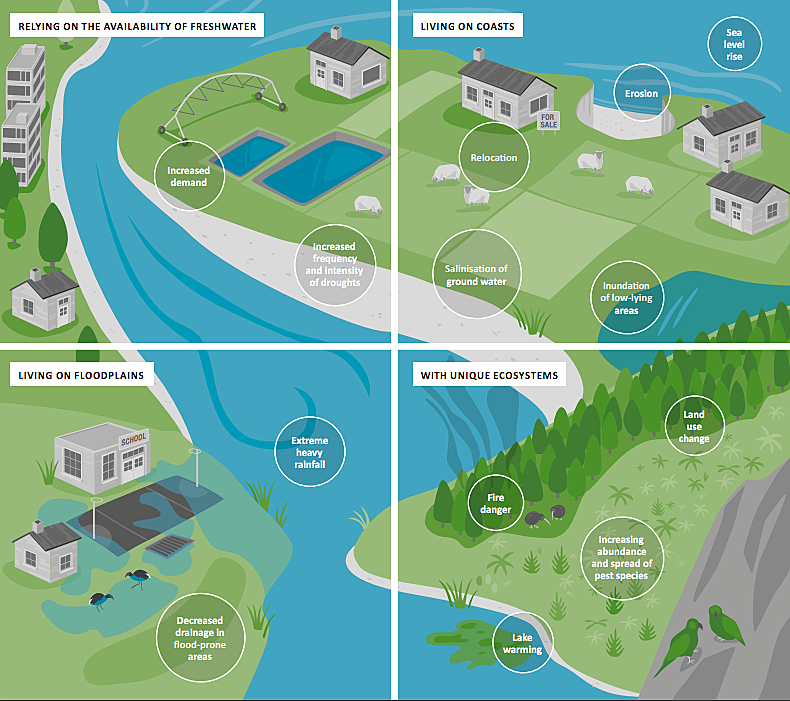

If anything, it’s not the inviting and cosy sketches of these futures that are persuasive, but their alternatives. The counterfactual of the ‘internet of things’ is a lifetime of getting up and walking over to the light switch. In contrast, the path we take instead of shooting for a green utopia is certain dystopia – extreme weather events, mass extinctions, food shortages and mass migrations of climate refugees that will make the current crisis in Europe look like a small geopolitical footnote.

The most challenging aspect of this is that many people will be required to live slightly less comfortable lives, facing some restriction of individual choice so that society as a whole is run in a truly sustainable manner.

Unfortunately, human psychology doesn’t really incline us to take seriously such a slow developing catastrophe – instead, it’s far easier to downplay the potential for disaster and search for prophets of a more comfortable future. Outside the bubble of sites like these, you’d be surprised just how much time a talkback radio/general media personality like Mike Hosking spends telling his listeners/viewers not to worry about climate change. You’d think he would at least be drawn to a high-end consumerist product like Tesla’s electric car, with its combination of ‘internet of things’ convenience mindset and pricey status symbol.

Yet Hosking hates electric cars with an unusual passion (as do many who comment beneath Herald articles, by Hosking or otherwise, on the subject). Perhaps it is because electric cars ultimately depend on collective solutions, relying on a system that provides renewable power to be truly valuable (hence they make more sense in NZ, where renewable sources presently make up 80% of electricity generation, than they do in the US). But any mass conversion of a vehicle fleet would still require far greater renewables capacity than we have now. Bluntly, the impact of electric cars will be limited unless the NIMBYs fighting against public wind farms and solar panel arrays are overcome. With the Hoskings, Johnsons and Abbotts of this world ready with scare quotes and pat answers, it is likely to be a battle.

For things to change, people need to be more excited about a green future utopia than a consumerist one, though the current bias seems to be the other way around. Environmentalists are in a bind, since if they talk only of the dystopic future that climate change will bring about then they are written off as doom and gloom merchants. Perhaps one way around this dilemma is to focus on how our generation will be viewed by grandchildren. Essentially, people need to believe that their efforts to advocate for a more sustainable society will make them like the forward-thinking protesters for civil rights and equality in the sixties and seventies, who are now held up as heroes of their generation. And this needs to be a view embraced by wider society, not just the small minority of the middle-class who currently make the bulk of the modern Greens voting base.

There also needs to be a visceral, society-wide disdain for those deny climate change or more insidiously find ways to defer action on it. Yet at the moment, there is far more focused opprobrium towards those who are sexist, racist and homophobic to polluters and their enablers. There isn’t even the terminology to make such accusations – calling someone “homophobic” is a powerful rebuke that people get ashamed and defensive about, but calling them a “climate change denier” is a far larger mouthful and doesn’t pack the same punch. Only once you are able to call someone a “polluter” (or similar punchy epitaph) and have it stick as a toxic label, will it feel like society truly owns climate change as a problem to be dealt with.

Too often climate change is instead seen as a problem that exists ‘over there’ – whether this means in a distant land or in a distant time period. What do we in New Zealand care if an indigenous Alaskan village has to move or India suffers increasing numbers of deaths each year due to heat waves? Not enough to curb our short-term comfort and economic well-being. In this way, climate justice dovetails with other civil rights issues of inequality and racism (given that it affects where you live and how healthy it is to live there) – if we care about these issues, then we have to care about climate change. But how many droughts and extreme weather events will have to hit New Zealand, before we admit that ‘over there’ is actually ‘over here’ too?

So which of these utopias is really going to come to fruition? I don’t want to sound like I’m hedging my bets, but probably both – to a minor, limited and inadequate degree. The green utopia will be marketed by stealth rather than taken by storm, packaged in an appealing way for a modern capitalist society. The likes of Tesla will disrupt old and unsustainable ways of doing things, but they’re not a government, or even a charity, and shouldn’t be expected to act like either.

In the meantime, a few gadgets from within the internet of things will cross over to mainstream use, though it will only be a small percentage of the population that can take full advantage of the possibilities and, in this way, the digital divide between rich and poor will grow ever deeper. And what will the upper echelon of society do with all the time that they’ve saved through technology? If the past teaches us anything, it probably suggests that they’ll simply work even longer hours just to keep up and assuage their status anxiety.

Jumping even further forward, it seems likely that few people in a hundred years time will fondly recall the internet of things. What we fawn and fret and strive for will seem like The Jetsons’ future-by-the-past, or even like idle Victorian gadgetry. They won’t remember Hosking, or Johnson, or Donald Trump. or how ISIS finally came to an end. Instead their main knowledge of our time will be that our generation continued to live to excess, just at the time when the world needed to reduce its carbon footprint and knew it. The wars in Afghanistan and Iraq might dominate headlines now, but will fade into insignificance in the same way that the collective memory of the Boer War and the Sino-Japanese War were erased by the exponentially more bloody first and second world wars. We cannot imagine the myriad forms these coming catastrophes will take, but we already know their cause.

Even within our lifetime, there will be a reckoning to be faced. When we speak to our grandchildren, will it be enough for us to point to a childhood fed on Saturday morning cartoon visions of flying cars and helpful robots, then apologise and meekly explain that we had an entirely different future in mind?