Uncovering What Time Buries in Obscurity

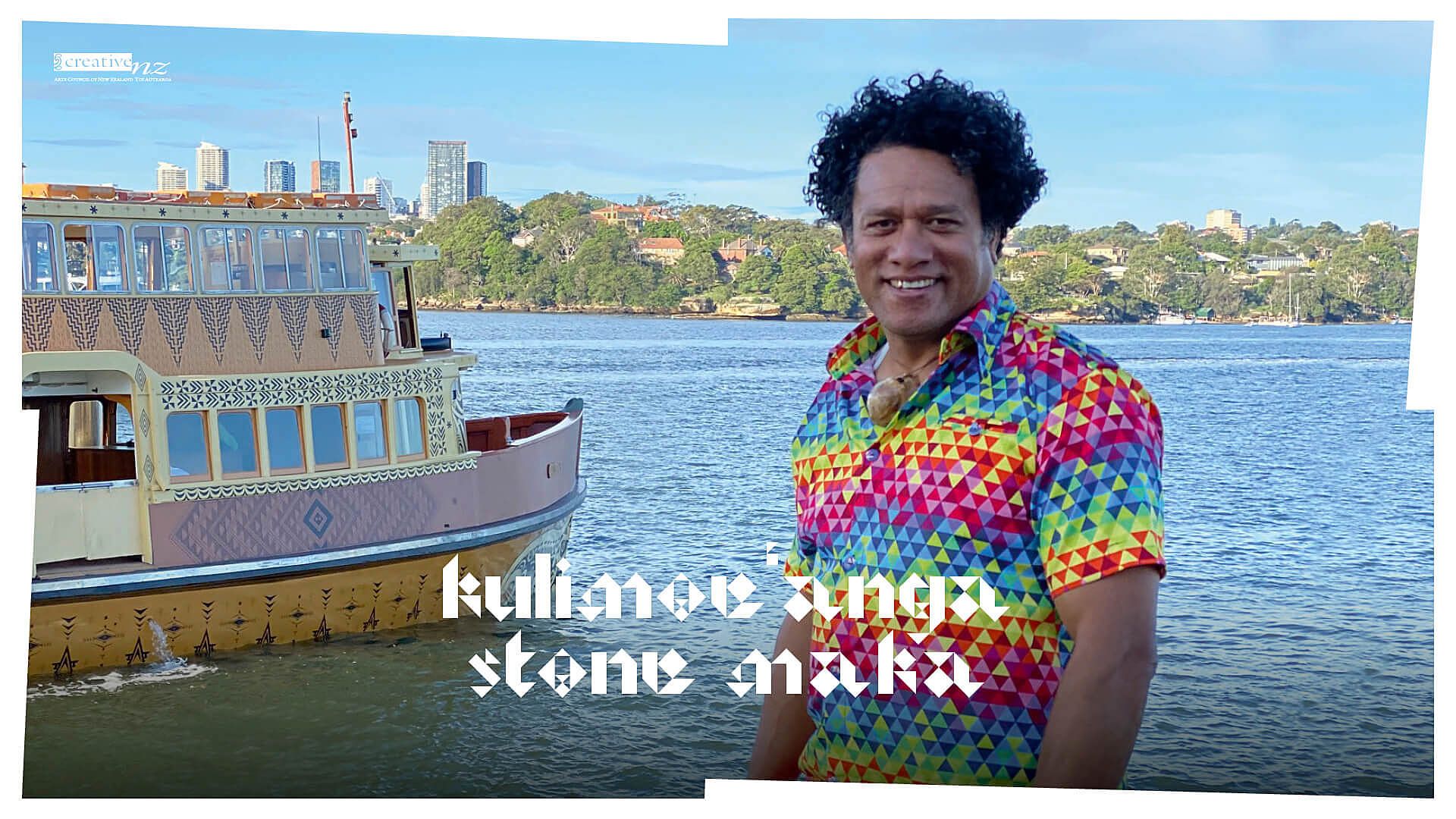

Painting with spider webs and rescuing the art that time buries in obscurity, artist Kulimoe‘anga Stone Maka writes on being exposed to abstract art forms his whole life.

We’re collaborating with Creative New Zealand to bring you the groundbreaking Pacific Arts Legacy Project. Curated by Lana Lopesi as project Editor-in-Chief, it’s a foundational history of Pacific arts in Aotearoa as told from the perspective of the artists who were there.

Heliaki Memories

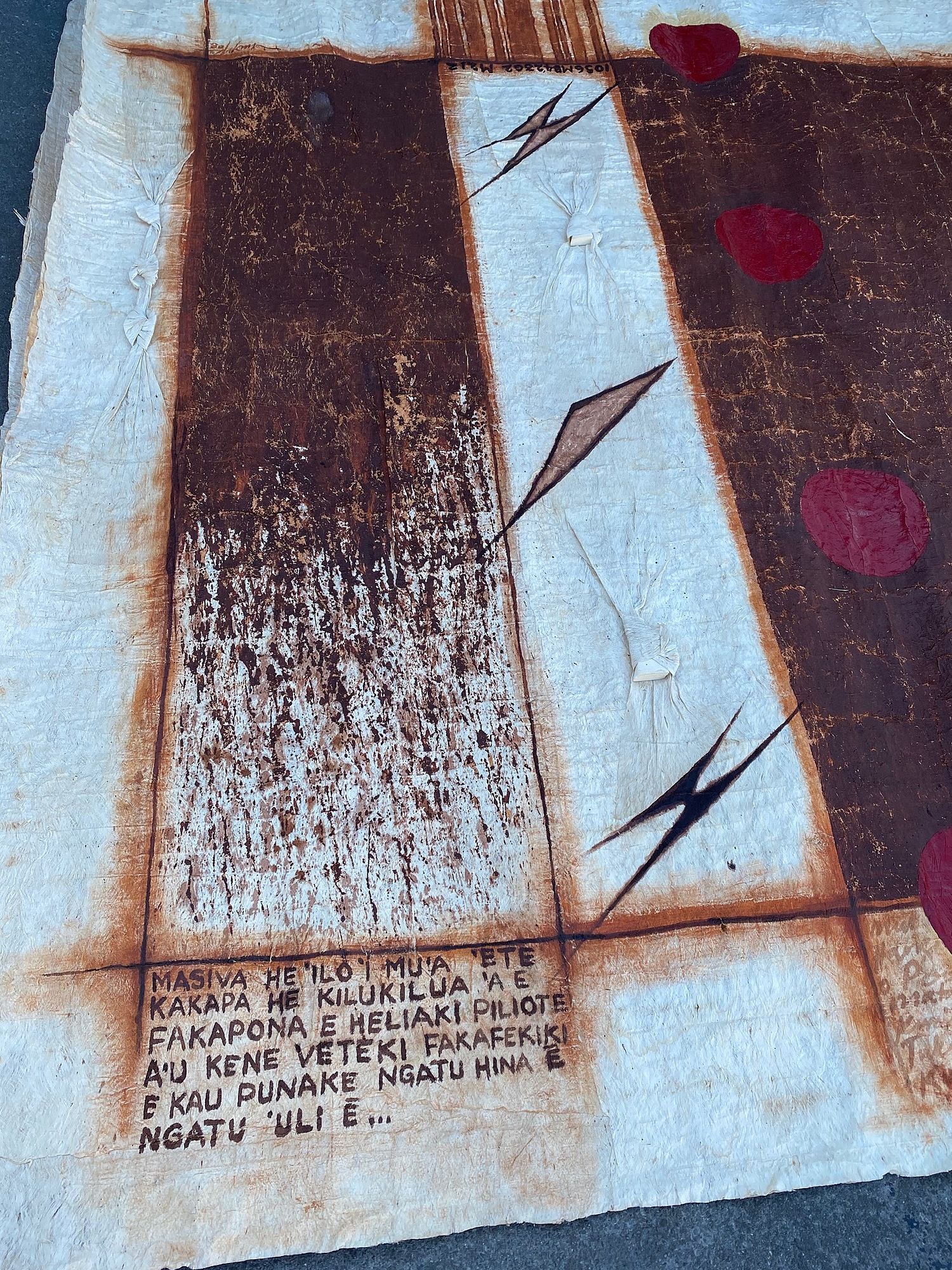

I hear the rhythmic beating of the ike (wooden mallet) on the tutu (mulberry-bark strip)-laden tutua (wooden anvil) from morning till night. There’s a Jumanji-esque feel to the drumming, as it pulses in my memories. I can hear the soft bristles of the fo‘i fā (pandanus seed) used to write on the ngatu (tapa). As it’s repeatedly dipped into the ink, I hear the dripping of the vibrant or deep reds, or the earthy browns before the brush is applied to the ngatu.

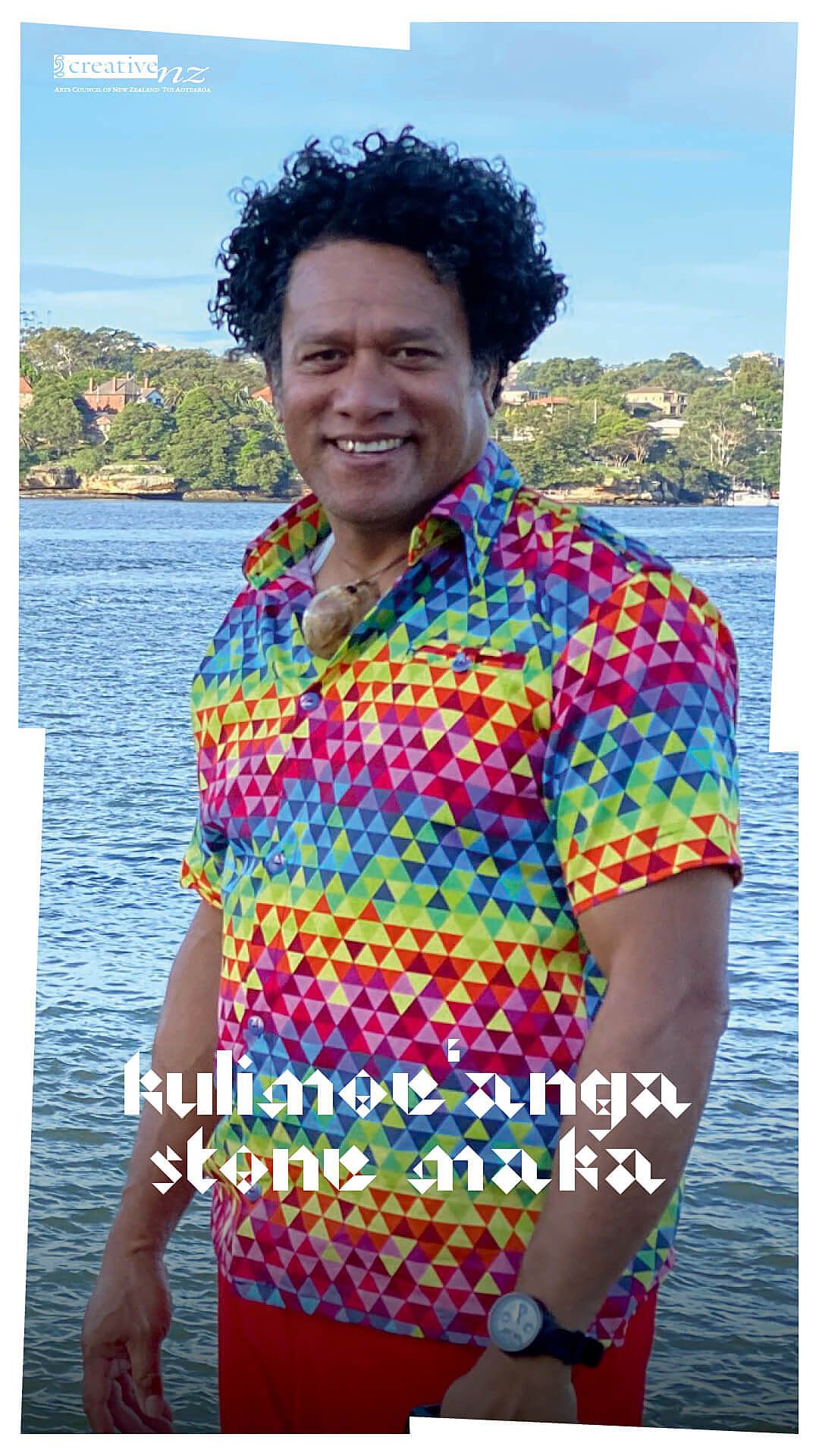

Kulimoe‘anga Stone Maka with heliaki painting, 2020. Image courtesy of the artist

I loved to sneak behind our neighbour Viliami Sikaleti’s old broken fence, sitting a little far off, to watch magical hands at work. The hands belonged to three wood carvers, Viliami Sikaleti, Steven Fe‘ao Fehoko and my dad, and a canoe builder, Tui‘one Pulotu, collaborating to create different abstract masterpieces, including a wooden figure of the Tiki (a traditional Tongan goddess). These were the first men to put art in my heart.

Ve‘etūtū Pāhulu (a well-known Tongan poet, composer and choreographer) often came to our home, to teach our village girls the traditional tau‘olunga and the boys the tūlafale, lakalaka and ma‘ulu‘ulu. This was in preparation for the annual Christmas performances in town that later travelled around Tonga. Another year I formed a little band comprised of my friends playing a home-made cello fashioned from a wooden box, strings and a stick; a home-made triangle formed from a piece of contorted steel; and a shaker made from beer-bottle caps nailed to a wooden handle. Before any group could take part in the Christmas performances, they had to pass a test conducted by the King’s composer, Ve‘ehala, in which they had to prove that the dialect and dance moves used in their songs and performances were fakamatāpule (metaphorical).

The Tongan language is made up of three dialects. The highest, reserved for the kings, is metaphorical; then there is the nobles’ dialect, with some metaphors; and finally the commoners’ simple dialect. We commoners show deference when we use the other two dialects. Tongan lyrics are usually indirect speech, as the analogies and metaphors used mask stories of warfare, love and even genealogy. With Tongan dances, hand and body movements tell a plain story for outsiders, but to the composer or choreographer there is a hidden meaning.

Tongan lyrics are usually indirect speech, as the analogies and metaphors used mask stories of warfare, love and even genealogy.

Another influential person in my life was my high-school art teacher, Professor Viliami Toluta‘u. He introduced me to modern art from the Western world. He taught us about Vincent Van Gogh, Michelangelo and Salvador Dali. We learned about Beethoven – and that although he became deaf, he could still make music through feeling. And in abstract art, you paint the feeling, not what you see with your eyes. He taught me about all the different art materials and art equipment one uses, and introduced me to printing and sculpting techniques. He opened my eyes and mind to seeing art as more than making decorative tapa art and selling it in the market, or making wood carvings to sell to tourists. His experiences and stories were the impetus for me to go overseas and see these art forms for myself.

I learned from an early age that our language, arts, dance, songs and stories are performed in heliaki (metaphorical form), and those heliaki help protect and preserve our culture.

In hindsight I realise that I’ve been exposed to these abstract art forms my whole life.

Kulimoe‘anga Stone Maka with heliaki painting, 2020. Image courtesy of the artist

Tupu‘anga

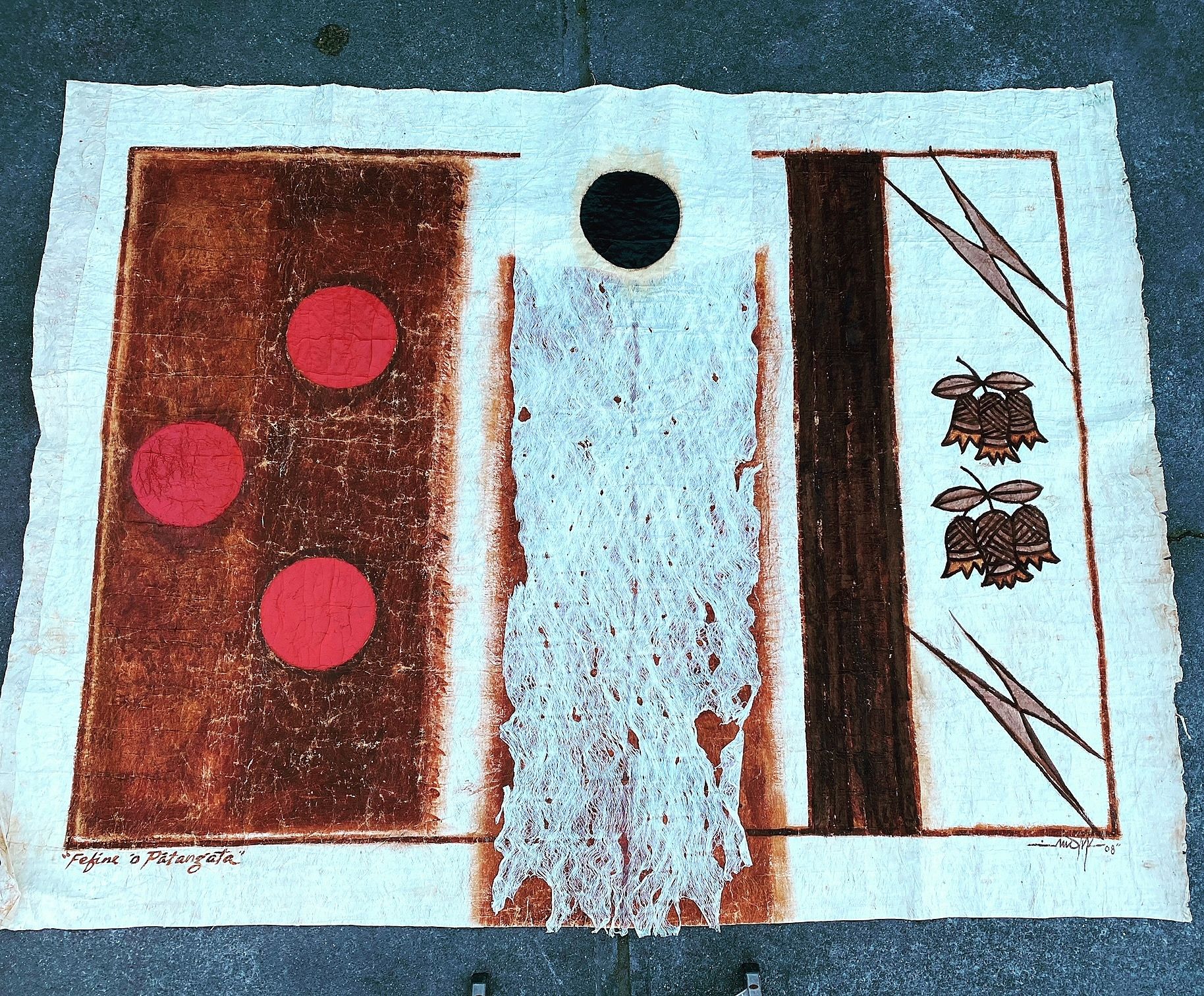

I was born in Tonga. I am the second youngest of 12 children and I have six brothers and five sisters. Before I was born, my family moved from their home in Talafo‘ou to a village called Pātangata, a wetland area close to the capital. We were poor in material possessions, but rich in happiness due to the simplicity of our lives. My mum was skilled at fishing and paid for us to get through school by selling her catch at the local fish market. My dad sometimes helped with the fishing, but would mainly sell his carved goods to make ends meet. When Mum wasn’t fishing, she was a skilled weaver and tapa maker.

I recall accompanying Mum to plant the hiapo (mulberry tree), harvesting them and then seeing my dad carve the tutua and the ike from the toa (ironwood) tree.

I would help to make the black ink and dark red dye from the koka tree and mangroves.

Fefine ‘o Pātangata, 2008. Image courtesy of the artist

Fakapona, 2008. Image courtesy of the artist

I was in Year 3 at primary school when I realised my teachers would always ask me to create artwork for the class. I was then chosen with another boy to represent our school in a national art campaign around preserving the environment. From here I continued to develop my talent and enter various national art competitions. It was at a Tongan Art Symposium in the late 1980s that I first met Filipe Tohi, Fatu Feu‘u and Johnny Penisula.

When I arrived in Aotearoa New Zealand it was the first foreign country I’d been to. It was a culture shock for me, but a journey of discovey. I was 25 and I had to relearn everything, especially the language, but thankfully I found the arts to be the same – they were my safety blanket. I also felt protected around Pacific artists in Aotearoa. I met John Pule and Nigel Brown in 1998–99 at the Morgan Street Gallery in Newmarket. Over the years I have met Andy Leleisi‘uao, John Ioane, Jim Vivieaere, Lily Laita, the Tuffery brothers and Dagmar Vaikalafi Dyck. Each and every one of them has created their profession in their own unique way, as a Pacific artist in Aotearoa.

My Passion

In 2005 I moved from Tāmaki Makaurau to Ōtautahi, and as I settled I realised I had moved to a very English city. There didn’t seem to be many Polynesian people, let alone Pacific artists around. I started to feel the same as I had seven years ago, as I’d stepped down from the plane. Again I found myself in a foreign place, and this time learning the language of rejection from art galleries. It seemed the Christchurch art scene had its own cliques that clung together and rarely let in fresh blood. At times I asked myself – does your art survive because of art galleries showing your work or does it survive because you’re passionate about what you do?

I’m an interdisciplinary artist, from humble beginnings on the island of Tonga. I’ve been in New Zealand for 24 years now and in that time I have graduated from the University of Auckland with a Bachelor of Visual Arts, become a professional artist and exhibited throughout New Zealand, and, more recently, internationally at the Biennale of Sydney 2020.

Toga mo Bolata‘ane, 2008–2010. Image courtesy of the artist

My artwork has always been steeped in Tongan culture and history, and I am grateful for a transformative conversation with my mum in 1998. I asked her about which other Tongan art forms I could paint, as it seemed as if all the Pacific motifs and art forms were already taken or utilised by the other Pacific artists. I was awakened and set out on my current path – in the renaissance of the ngatu tā uli (black tapa). I have taken the traditional art form of the ngatu tā uli, reserved only for nobility – which at times buries it in obscurity for many people (including Tongans) – and given it new life through the lens of fine art. In turn this has given others insight into the sacred art form, and in the same breath enables Tongans to be proud of a dying art form. By doing so I hope to bridge the gap between the past and the hopeful future. I believe that abstract art in the Pacific is one of the most expressive and pure forms of art making, and so my paintings draw attention to the formalism and abstraction inherent in Pacific art since the 18th century.

I chose the ngatu tā uli because it encapsulates the abstract in nature and form, and is the core of my art practice. It makes me feel safe to share my ideas because there is a plain message to satisfy outsiders, but a hidden and deeper meaning for myself and anyone willing to diligently search it out.

One of my father’s quotes, “Oku mālie ange ‘a e fa‘u ‘i hono ‘ufi‘ufi‘i he‘ene Hualela. He ‘oku ifo kihe ‘atamai fifili ‘i hano foa‘i”, translates to “The struggle journey one takes to unveil the true meaning of a creation always makes the reward sweeter, when they succeed.”

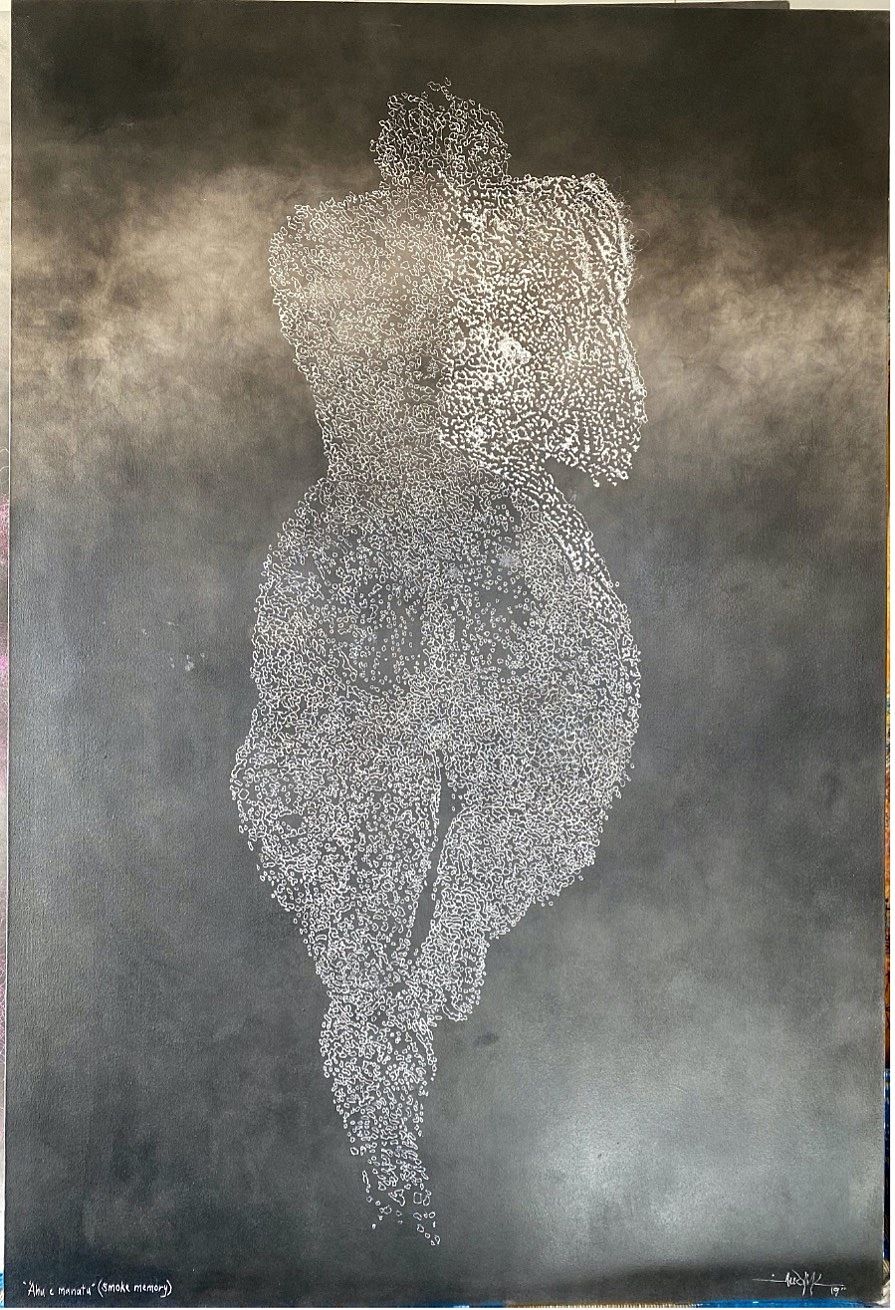

In 2003, as part of my final-year university assessment, I traveled to Tonga to research the origins of the black tapa. I began experimenting and creating the black tapa by painting with smoke, which was born from the traditional Tongan methods of smoking, e.g. mats and food. When I started, I used the familiar traditional methods such as burning leaves, nuts and a variety of tree bark to get black smoke. I collected the smoke residue and mixed it with coconut oil and red dye to make black ink, and I painted on traditional ngatu. The artworks I developed and exhibited from this process were considered innovative.

Fast-forward a few years and my work continues to derive inspiration from the ngatu tā uli, my foundation, while finding ways to evolve different elements. My ultimate aim is to take the ngatu tā uli to the next contemporary level. I have experimented with burning different media to try and realise more smoke colours. I’ve used mosquito coils and ‘collected’ the smoke on canvas. This has resulted in the creation of an additional smoke colour – brown. This piqued an interest in getting other colours, which I achieved by using smoke bombs to acquire colours such as green, blue, purple and red. The works I subsequently created and exhibited were considered ground breaking.

To peel back to simplicity, more recently I returned to smoking my canvas in black and trialled drawing on the smoked canvas. Wispy, wiry and writhing lines, which began as abstract paintings, later combined to conjure up more figurative images. At times these paintings have been described as haunting, mesmerising and ethereal.

‘Ahu e manatu, 2019. Image courtesy of the artist

From a fleeting thought of the possibility of using real spider webs in a painting in 1999, I began investigating this in 2004. The fragility of this medium meant constant failures, yet I persevered and was finally successful in 2017, when I completed my first spider-web painting on smoked canvas. It was humbling to release this new work to the public in a group show in 2020, following the first lockdown wave, at Christchurch’s Central Art Gallery, to gasps of wonderment and disbelief.

*

This piece is published in collaboration with Creative New Zealand as part of the Pacific Arts Legacy Project, an initiative under Creative New Zealand’s Pacific Arts Strategy. Lana Lopesi is Editor-in-Chief of the project.

Series design by Shaun Naufahu, Alt group.