Venous Flow: Psychic and Somatic Pain in the Work of Fiona Pardington

There's a sense of unease in the work of Fiona Pardington. Imagery is recontextualised and thrust into alternate worlds, where trauma and beauty are inextricably linked.

The following essay is from the forthcoming collection of essays, interviews and images that accompanies the touring exhibition of Fiona Pardington's work, A Beautiful Hestitation.

Writing on the uncanny in the work of the American novelist Henry James,[1] Virginia Woolf noted how ‘the spiritual and the carnal meeting together produce a strange emotion – not exactly fear, nor yet excitement.’[2] The psychic novellas James wrote in the late nineteenth century enthralled audiences with tales of the supernatural and ‘abnormal states of mind’.[3] In stories like The Turn of the Screw (1898), he wrote of a world in which the past extends into the present. For the protagonist of the story, Woolf tells us, ‘it was the sudden extension of her own field of perception’ which most alarmed her.[4] ‘The horror of the story comes from the force with which it makes us realise the power that our minds possess for such excursions . . . when certain lights sink or certain barriers are lowered, the ghosts of the mind, untracked desires, indistinct intimations, are seen to be large company.’[5] Like Woolf’s description of James’s novella, these are the kinds of excursions that Fiona Pardington’s photographs take us on.

In one of Pardington’s early images, Oracle No.2 (1987), we see the hands of an elderly woman half covering a face lined with age. Behind the hands are piercing eyes. There is a wedding ring, a few wisps of grey hair and the edges of a woollen cardigan. Another image shows the same woman, again gazing directly at the camera although this time she is swathed in a diaphanous fabric. There is something hard to define in that gaze, something mildly unsettling. These are images of Pardington’s grandmother, Dorothy. In another photograph, Premonition (1983), Dorothy is now the grandmother she has always been, her knees covered with a blanket. She is smiling benignly, yet in the upper third of the image there is a ghoulish apparition that appears to be approaching the woman from behind her chair. Is it fear or a sense of dislocation that I feel looking at that figure? In the next image the grandmother is reading a book, Sphinx, by Robin Cook, a writer of suspense novels. Finally we see Dorothy with a younger woman, the artist’s mother, Janice, smiling as the elderly woman peers out in a strangely reticent way from behind a curtain.

Fiona Pardington, Sphynx, 1983

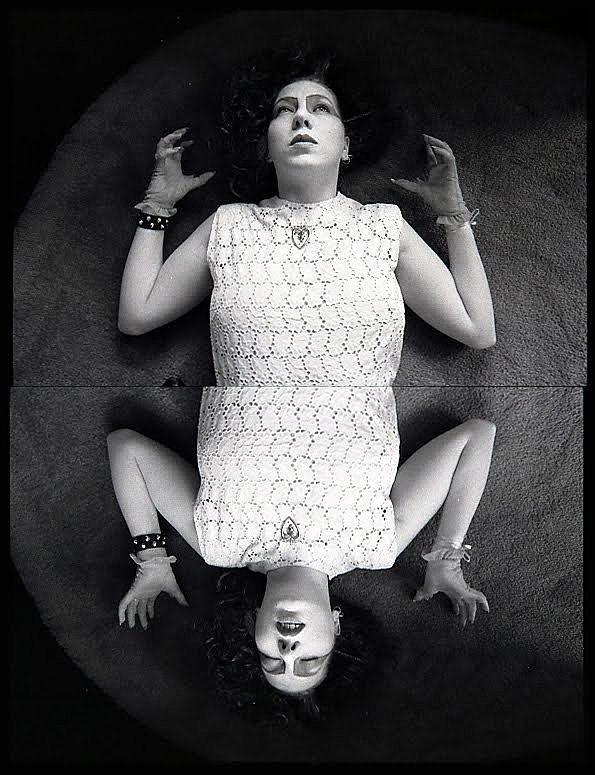

There is a palpable sense of psychic unease in this group of images. The titles tell the story: Oracle No.2; Premonition; Dorothy as a White Witch (1983); Sphinx, Parau Street, Mount Roskill (1983). It is an unease that sweeps like waves of emotional disturbance through Pardington’s oeuvre, beginning with these early works and continuing through to the most recent. At times that unease feels shrill, carping almost, as if the artist is pressing a point. Take Manifesta (1982), in which the arms are raised awkwardly like those of a madwoman or a soothsayer, hands clawed, eyes angled up in a pose of exaggerated divinity.

Fiona Pardington, Manifesta, 1982

In Kim as Pacific Undine (1982–83) the image is fractured like a kaleidoscopic vision of Sigmund Freud’s ‘crystal fracturing of the mind’, where pathology ‘points to a breach or a rent’ and the mind cleaves like that of a crystal.[6]Perhaps the most disturbing of these images is Isobel’s Ectoplasm (1992). Soon after the invention of the daguerreotype, those seeking alternate worlds or a means to communicate with the dead turned to photography. Many of the photographs were simply double exposures, and claims that a gauze-like substance or ‘ectoplasm’ excreted from the body was a flow of psychic energy were acknowledged at the time as a hoax. For Pardington, however, images like Manifesta and Isobel’s Ectoplasm form part of a continuing fascination with variable states of mind and the possibilities that photography provides for extending our understanding of what lies beyond the visible world, and the points of rupture which give us access.

Images like Manifesta and Isobel’s Ectoplasm form part of a continuing fascination with variable states of mind and the possibilities that photography provides for extending our understanding of what lies beyond the visible world, and the points of rupture which give us access.

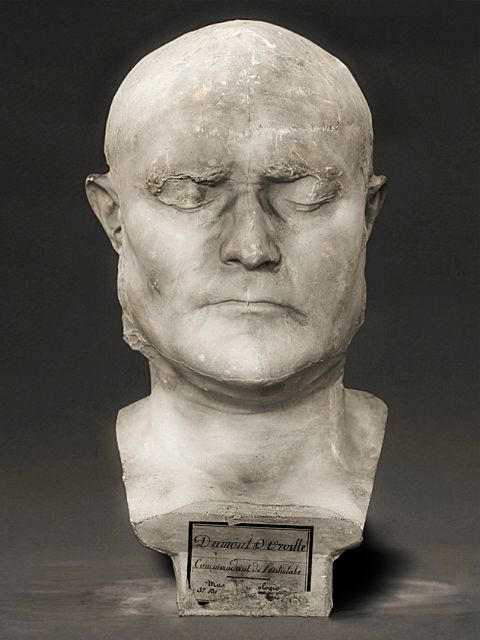

Other early works generate a similar sense of unease. In Joseph with Face Mask (c. 1987), Joseph stares directly at us, as at the photographer, with a white mask and an unflinching gaze that intimates a latent violence, perhaps, or something that takes us into a darker world where the past or the future impacts the present. The birds that appear in Pardington’s still life photographs and her recent birdwing diptychs are often taxidermied, wounded or mutilated specimens. In every instance, the birds have undergone some form of trauma, including extinction. Cast heads from French museums (the Āhua images, photographed in 2011) reflect a colonial history of subjugation, racism and the discredited science of phrenology. For Pardington these images lead us back in time through the light of the exposed photographic image to the light that played on the figure at the moment the cast was made. In this way, a direct connection is made between us the viewer and the individual from whom the cast was taken, who in that moment suffered the psychological and physical pain caused by one culture’s domination of another.

Although the initial impression of much of Pardington’s imagery is a richness that in more recent photographs is vivid with colour and often exquisitely beautiful, behind that beauty is a traumatic world view that extends from the spiritual and acutely dysphoric to a world saturated with a pain that is both psychic and somatic.

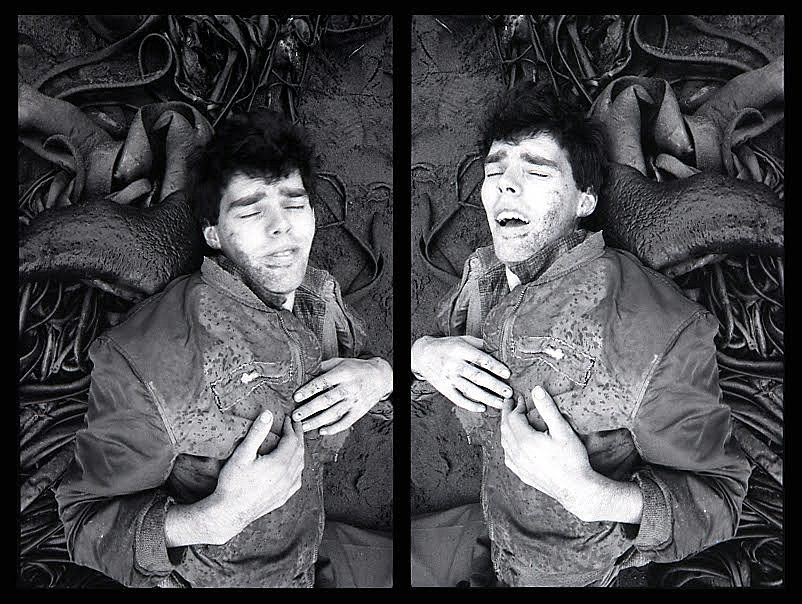

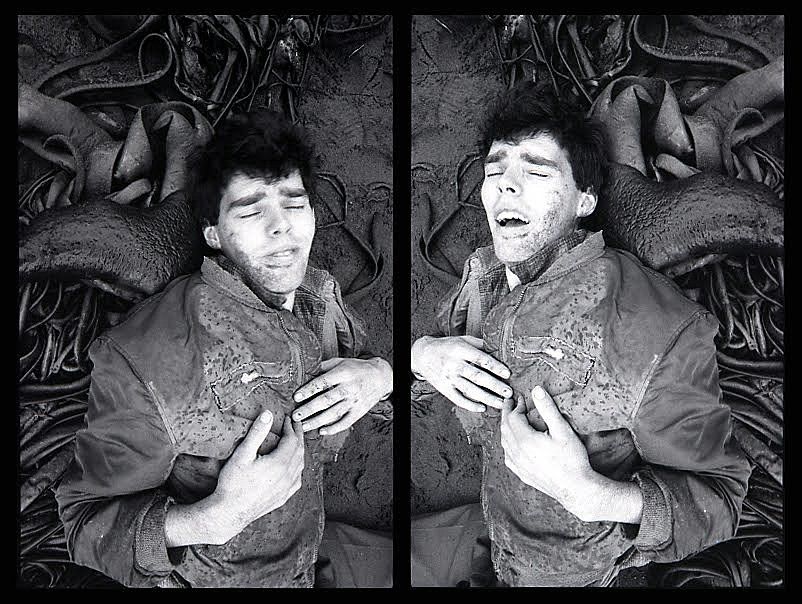

In looking at the proof sheets for Pardington’s early works, it becomes apparent that the disruptive or uncanny images of Dorothy and Patrick, even those that appear to be portraits, are deliberately staged in a way that is intended as more than playacting. In the proof sheets of Dorothy there are numerous images that show the smiles of a beloved grandmother, warm and indulgent, but the image chosen is one of the few showing anguish or fear and a psychological distance. Similarly with the images of Patrick (Patrick as the Young Korymbos, 1982). These photographs are from the artist’s time at the University of Auckland Elam School of Fine Art, and although Patrick, the subject and a fellow student, is shown playing around and pulling humorous faces in most of the shots, it is the image depicting an internal anxiety and a more desperate demeanour that Pardington has chosen. These are not moments captured in the tradition of providing psychological insight into subjects, but images where the subjects are ‘acting out’ according to the photographer’s directions.[7] There is no doubt that it is a certain psychological pose that Pardington is seeking to define. But what is the underlying subtext of these works and the many subsequent works that carry that same sense of unease, whether a person, a taoka or an assembly of objects as in the still-life photographs?

Fiona Pardington, Patrick at Anawhata, 1982

In Invention of Hysteria: Charcot and the Photographic Iconography of the Salpêtrière, the French art historian and philosopher Georges Didi-Huberman investigates the intimate and reciprocal relationship between psychiatry and photography in the late nineteenth century. Within this framework, he illustrates the crucial role of photography in the conceptualisation of hysteria. Salpêtrière was the largest asylum for women in France at the time and was renowned for its abuse of patients and the horrific conditions in which the women lived. It included not only the mentally ill but also those with epilepsy and venereal disease and the destitute. ‘In the last few decades of the nineteenth century, the Salpêtrière was . . . a kind of feminine inferno, a citta dolorosa confining four thousand incurable or mad women. It was a nightmare in the midst of Paris’s Belle Époque.’[8]

Taken under the aegis of medicine, photographs of the time show women diagnosed as suffering from hysteria. They depict writhing patients with upward stares and clenched hands. These are often young women with their clothes askew, revealing limbs and partially covered breasts. The images that were said to bear witness to hysteria but were instead a kind of sexual voyeurism and fetish. Hair, hands, eyes and feet became a spectacle. ‘Fevers were measured rectally . . . and vaginally.’[9] In every instance the women’s bodies were exploited to fit a theory but also to allow the male, medical gaze to take in every aspect of their sexuality. In Psychopathia Sexualis (1886),[10] a favourite text of Pardington’s which she has carried around with her for 30 years, the author Richard von Krafft-Ebing writes:

Erotic fetichism makes an idol of physical or mental qualities of a person or even merely of objects used by that person . . . thus originating strong emotions of sexual pleasure. Analogies with religious fetichism are always discernible; for, in the latter, the most insignificant objects (hair, nails, bones, etc.) become at times fetiches which produce feelings of delight and even ecstasy.[11]

In his investigation of Salpêtrière and the many medical photographs taken of the women, Didi-Huberman reveals that these are in fact images of women ‘acting out’ the symptoms of hysteria under the tutelage of the principal clinician, Jean-Martin Charcot. ‘I am nearly compelled to consider hysteria, insofar as it was fabricated at the Salpêtrière . . . a chapter in the history of art.’[12] The invention of hysteria as described by Didi-Huberman was shown to be what it had always been: a ‘spectacle of pain’, the pain of confinement, of mental and physical illness, and the trauma of severe poverty.

The question then remains: is this what we see in the ‘acting out’ in Pardington’s photographs, this combination of fetish and a spectacle of pain? The answer is yes – it is the pain that the artist sees around her, in women, in her whakapapa, and within herself, with her own at times harsh experience of life, in a patriarchal and colonial past and in the pain associated with sexual exploitation. In some photographs that pain is more clearly defined: in the inflicting of wounds, in works like Self Portrait with Stitches (1990) and Heavy Penance (1992) where the talons of the gloved woman scrape the face of her lover; and in the One Night of Love series of long-forgotten photographs of young women in the 1950s and 60s, acting out fantasies for the male viewer.

It is the pain that the artist sees around her, in women, in her whakapapa, and within herself, with her own at times harsh experience of life, in a patriarchal and colonial past and in the pain associated with sexual exploitation

Masochism and sadism also play a part in this combination of pain and spectacle. ‘The pathological facts of masochism and sadism show that mental peculiarities may also act as fetiches, but in a wider sense.’[13] We see this in Charcot’s exploitation of the Salpêtrière women and in the phrenology casts that speak of a racist and colonial past, the pain of criminals, the insane, guillotined assassins, syphilitic sufferers and the sexual and sadistic pain that underscores the image of the cast skull of the Marquis de Sade.

Fiona Pardington, Portrait of a life-cast of Dumont d'Urville, 2010

The association of lust and cruelty [in sadism], which is indicated in the physiological consciousness, becomes strongly marked on a psychically degenerated basis, and that this lustful impulse coupled with presentations of cruelty rises to the height of powerful affects.[14] ‘The quality of the sadistic acts,’ Krafft-Ebing tells us, ‘is defined by the relative potency of the tainted individual.’[15] ‘Tainted’ is a word used often in Psychopathia Sexualis. Not only to refer to the criminal or insane but also in writing about sexual practices once considered deviant, such as masturbation. ‘Lombroso . . . has collected a number of cases of children affected with very decided hereditary taint.’[16] ‘Taint’ in this usage refers to what was once thought to be a mental disease or pathology.

In 1994, Pardington exhibited a series of re-photographed medical images under the title Tainted Love. By removing the works from a medical context and exhibiting them with new titles, underlying tensions were exposed. In Sally and Donna (1994), for example, a photograph purportedly showing the ‘extent of the female breast’ the sexual voyeurism is clear. In Heartsick (1994), in which a young woman is shown about to have her trachea dislocated, we see instead a sadistic act of strangulation. Each image adds to the litany of pain and suffering. The title of Host (1994) suggests the mouth held open to receive Holy Communion, but instead we see the curse and pain of another kind of host. Venous Flow (1999) shows us an arm with a stretched and exposed vein that one might assume has been prepared to take a needle. The man’s extreme thinness, the washed-out jeans and the seemingly expert stretching of the protruding veins recall many images of intravenous-drug users. The original purpose of the photograph is not revealed, but here in this context it presents the abyss of addiction and the epitome of social or mental disorder.

Unlike the images of the women of the Salpêtrière, One Night of Love and Pardington’s early portraits, these figures are not acting out their symptoms. Instead Pardington is presenting us with an alternative world, taking each image into a different reality that expresses the pain and trauma of sexual violence, addiction and voyeurism.

The title Venous Flow, amid the complexity of Pardington’s allusions, is also a reference to masochism – the inflicting of pain on oneself. It is ‘the counterpart of sadism in so far as it derives the zenith of pleasure from reckless acts of violence . . . it forms a gradation of the most abhorrent and monstrous to the most ludicrous and absurd acts (the request for personal castigation, humiliations of all sort, passive flagellation, etc.)’.[17] Austrian writer Leopold von Sacher-Masoch, after whom the concept of masochism was named, is another of Pardington’s favourite authors.[18]In his novel Venus in Furs (1870), Sacher-Masoch relates the tale of a young man who is so infatuated with a woman that he seeks to become her contractual slave. Her only obligation is to always wear fur and to dominate him in any way she pleases. The novel questions male dominance in language that is highly erotic.

It is indescribable the feeling of being abused by the fortunate rival of an adored woman. I shrank under the shame and despair. The most shameful part was that in my appalling situation I began to feel a sort of fantastical supersensual enjoyment under Apollo’s whip and the cruel laughter of my Venus . . . finally I clenched my teeth in impotent rage and cursed my sensual fantasy.[19]

These concepts of female dominance and fetish are played out in many of Pardington’s images, but most specifically in Proud Flesh (1997). Pardington presents the long muscular curve of the back of a male figure who is reclining on furs, the soft white flesh of buttocks and legs draped in fabric. The model’s head has an almost completely severed ear that has been stitched with heavy black thread. They are images that present pain as fetish but also luxury, decadence and a highly sexual female gaze.

The torn ear that Pardington shows us in Proud Flesh embodies the physical and psychological pain that is continually present in her work. Within that imaging of pain, however, there is always beauty, the beauty of an exposed wound. Something is only beautiful, Pardington once told me, because of its proximity to death. The French author Jean Genet writes of wounds in his analysis of the works of the painter Rembrandt van Rijn and sculptor Alberto Giacometti. Genet, the third in the trilogy of writers favoured by Pardington who form the basis of this essay, lived a life of extremes, of marginality and petty crime, and was incarcerated at the age of 15 in a prison that held children from as young as six.[20] In The Thief’s Journal Genet relates the events of his life: ‘the love, the hatred, the championing of the downtrodden, the lust for the transgressive elements in life, the extremes of abjection and exultation’.[21]

In his analysis of Rembrandt’s self-portraits, showing Rembrandt’s process of ageing, Genet sees images that are ‘physical emanations of disintegration that intimate a wound as the core of the human body . . . that determining wound becomes ever more apparent as the image increasingly intersects with death’.[22]

Have you ever had a wound, on your elbow for instance, that has become inflamed? There is a crust there. With your fingernails, you lift it up. Underneath, the threads of pus which nourish that crust stretch back a long way . . . every physical component, however infected or abject, possesses its own magnificence.[23]

Genet harboured the same preoccupations with the work of his close friend Giacometti as with the self-portraits of Rembrandt – an intense interest in the association between the human figure and death: ‘the wound, the disintegrating figure and the revelation of human identicality . . . [had] an illuminatory impact of beauty for Genet’.[24]However, as Genet’s biographer Stephen Barber writes, the difference between Rembrandt and Giacometti in their depiction of that wound is that while ‘Rembrandt articulates it with infinite slowness, in tension with death, over a lifetime of self-portraits, Giacometti transmits it immediately, pre-eminently through the gaze that moves with volatile speed between his own eyes, those of his figures and those of Genet himself. . . . Even Giacometti’s own pulverized, dust-engrained body emanates that wounding for Genet’.[25]

Just as Genet would remain preoccupied ‘with the aura of death . . . and with the need to make discoveries in the most obscure or unforeseen places’, so has Pardington. The ‘wounds’ that Genet shows us, which inevitably develop into the putrefaction of the abject and discarded, underscore every image in Pardington’s work. As we move through the decades of her photography, the physical and psychological pain of that wound expands and each image becomes more intensely beautiful as it moves towards death. We see this intensity building from the first works of her grandmother, Dorothy, through the Measuring Love by Suffering sequence and Proud Flesh, the medical images whose subjects are never far from ruination, the still lifes with their discarded carcasses of birds, pests and environmental detritus and in the Kāi Tahu women of Wahine Pātere, Wahine Pānekeneke (2013) and EREWHON (2012) with their inverted figures of birthing soon to be followed by death and their descent into the underworld.

Take as a final image the beauty of the harrier hawk wings in Barbara’s Kahurangi (2012). These are the darkest of the artist’s series of wings, both chromatically and in their realisation, and like that of a Caravaggio painting, the violence and the darkness of humanity and of nature hover close to the surface. Wings spread, as if in flight, show the exquisite beauty and magnificence of the bird’s feathers. And yet, while it is beautiful, it also embodies trauma; this bird was found dead on the side of a South Island road. Pardington hacked off the wings with a small penknife, and, with the body removed, stuffed the wings into a plastic bag and smuggled them onto a plane as hand luggage. There is beauty in the image; there is also blood and guts, maiming and pain.

Throughout Pardington’s work there is pain that is acutely of this world. It is physically violent, exploitative and at times highly sexual and fetishistic, but there is another pain, a psychic pain that is otherworldly, relying on sensitivity to the photographic medium. It is a pain that is held up to us in all its manifestations as a spectacle for us to know and acknowledge.

Read our interview with curator Aaron Lister here

A Beautiful Hesitation

Fiona Pardington

Victoria University Press

$70

Notes

[1] Thank you to the artist for drawing my attention to the following article: Marjorie Sandor, ‘Something’s Wrong in the Garden: The Uncanny and the Art of Writing’, The Masters Review (blog), 28 November 2015

[2] Virginia Woolf, ‘Henry James’s Ghost Stories’, in The Complete Works of Virginia Woolf (Delphi Classics, 2012), Kindle edition.

[3] Woolf, ‘The Supernatural in Fiction’, in The Complete Works.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] ‘crystal fracturing of the mind’ is a reference to Freud’s concept of the mind splitting along predetermined fault lines in the same way a crystal fractures.

[7] The psychological term ‘acting out’ refers to a form of behaviour where the subject performs an action that is destructive either to themselves or to others. Freud’s belief was that patients ‘act out’ conflicts rather than remembering what they have forgotten or repressed.

[8] Georges Didi-Huberman, Invention of Hysteria: Charcot and the Photographic Iconography of the Salpêtrière, trans. Alisa Hartz (Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2003), xi.

[9] Didi-Huberman, Invention of Hysteria, 179.

[10] Richard von Krafft-Ebing was a Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Vienna in the late nineteenth century. A highly regarded clinician and teacher, his book Psychopathia Sexualis: The Classic Study of Deviant Sex was first published in 1886. Krafft-Ebing was the first to consider sexual deviancy a mental disease rather than a ‘moral defect’. Although Psychopathia Sexualis now suffers from the lack of sound scientific knowledge at the time, it remains in certain aspects highly relevant.

[11] Richard von Krafft-Ebing, ‘I. Fragments of a System of Psychology of Sexual Life’, in Psychopathia Sexualis: The Classic Study of Deviant Sex, trans. Franklin S. Klaf (New York: Arcade Publishing, 2011), Kindle edition.

[12] Didi-Huberman, Invention of Hysteria, 4.

[13] Krafft-Ebing, ‘I. Fragments of a System of Psychology of Sexual Life’, in Psychopathia Sexualis.

[14] Krafft-Ebing, ‘IV. General Pathology’, in Psychopathia Sexualis.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Pardington’s influences have seldom been other artists but instead philosophers and writers.

[19] Leopold von Sacher-Masoch, Chapter 15, in Venus in Furs (Dorchester: Stiletto Books, 2013). Kindle edition.

[20] Edmund White, introduction to Jean Genet by Stephen Barber (London: Reaktion Books, 2004), Kindle edition.

[21] Barber, ‘The Thief’s Journal’, in Jean Genet.

[22] Barber, ‘Rembrandt and the Wound’, in Jean Genet.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Barber, ‘Giacometti’, in Jean Genet.

[25] Ibid.