Wharenui Harikoa is what dreams are made of

Briar Pomana (Ngāti Kahungunu, Rongomaiwahine, Ngāti Rakaipaaka) falls down the enticing crochet rabbit hole of artists Lissy Robinson Cole and Rudi Robinson, reflecting on the role ringatoi Māori play in our current realities and beyond.

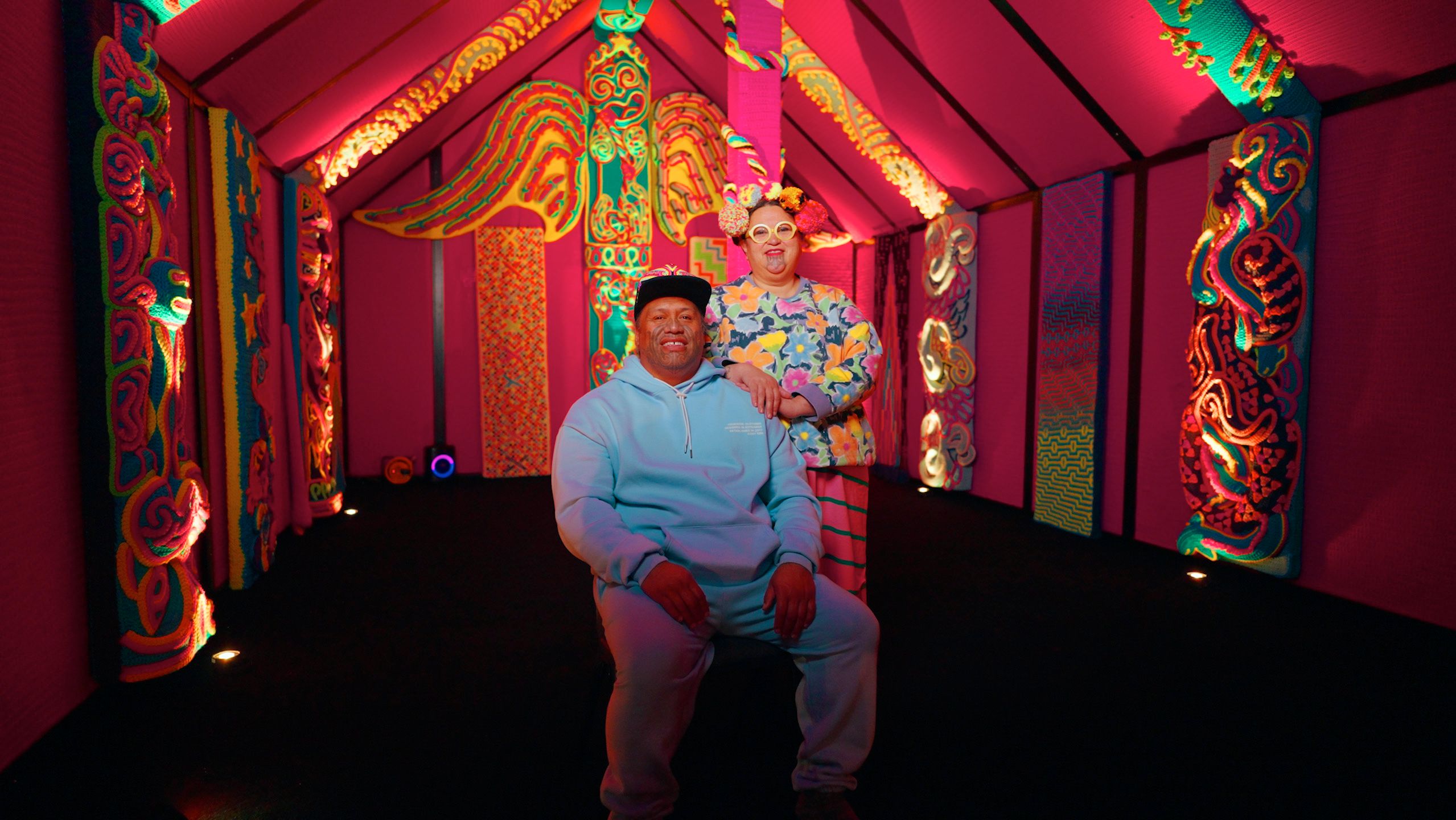

In 2022, Lisy Robinson-Cole (Ngāti Hine and Ngāti Kahu) and Rudi Robinson (Ngāti Paoa, Ngāruahine, Waikato, Te Arawa, Ngāti Pahauwera) exhibited Wharenui Harikoa at The Dowse in Wellington and with it, my Instagram feed was adorned with the most insanely crafted neon-crochet pou. Described on The Dowse’s website as a ‘refracting prism of Tūpuna inspired light that shines across the sky like a rainbow’, Wharenui Harikoa is a dream space that is an intersection of the past, present and future. Constructed out of love and 5000 balls of wool, this project has been in the works for a few years now. From the beginning of their journey, Lissy and Rudi have vocalised their dreams to create this crocheted wharenui. It’s an ambitious mission, but one the couple are up for, and it doesn’t look like they’re slowing down anytime soon.

I first came across Lissy and Rudi’s work at Vunilagi Vou gallery during the opening of their Fat February event in Otāhuhu 2020. This was before the pandemic had hit and one of the last public facing events a lot of us were fortunate to attend. We were set to be blessed with a fat fashion show curated and designed by Infamy Apparel’s Amy Lautogo, and the gallery space was filled with a gaggle of glamorous, gorgeous Indigenous folk – Lissy being of this crowd. At this time, Lissy’s car was completely covered in crochet as a part of an art piece called Joy Ride and their first exhibition Ka Puawaitia: Coming to Fruition was opening later that year with crochet wheku. I don’t know if Wharenui Harikoa was in the works, or even in Lissy’s mind, at Fat Feb, but what a privilege it is to witness the progression of their creativity.

In writing this article, I greedily consumed all of the interviews, podcasts, blog posts and pretty much anything I could get my hands on that talked about the ingenuity and journey of Lissy and Rudi. Qianne Matata-Sipu’s (Te Waiohua, Waikato, Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Pikiao, Cook Islands) podcast and pukapuka Nuku was one of my first indulgences. Nuku was a project over a few years where Qianne, creator and host travelled across the motu interviewing and sharing in wānanga with wāhine Māori and sometimes more broadly wāhine o le Moana. Lissy was ‘Nuku number one’, Qianne’s first interview. In the episode, Lissy spoke openly about a number of things that contributed to finding her path – one of which was the realisation that she did not have to be confined to a singular life journey. She could start at any time and feed into her purpose, regardless of age, status or ability.

Wharenui Harikoa. Supplied/Waikato Museum

My mum and I went to see Wharenui Harikoa where it currently sits in Waikato Museum at the beginning of this year. The trip was heavily anticipated by the both of us, in fact the morning of, my mum made at least four phone calls to various whānau back in Gisborne about our little roady to the wharenui. There were a number of people transitioning in and out of the space, almost floating like Patupaiarehe.

We made our way around the wharenui, exactly as we would if we were manuhiri on any other marae and were quickly advised by kaimahi that we weren’t to touch the exhibition. Resisting the urge to reach out and stroke the pou was difficult – the different textures and patterns of each figure seemed to elicit something guttural in all of us manuhiri. The emotional pull to each corner of the whare was strong. A mixture of nostalgia, comfort and in a lot of ways, grief washed over us in waves.

Wharenui Harikoa is more than an exhibition, it is a transformational space of liminality and an evolution of taonga tuku iho. Not only did each pou represent a whetū of the Matariki cluster, they also were figures of whakapapa. In the pou, I saw my mum, my Nanny, my Papa and other tīpuna reflected. It would be quite easy to lay down in the wharenui and look up at our kāhui whetū forever.

Wharenui Harikoa detail. Photo credit: Briar Pomana

In a room next to the wharenui was a film piece directed by Hāmiora Bailey (Ngāti Huarere, Ngāti Porou ki Harataunga) and choreographed by Jack Gray (Ngāti Porou, Ngāti Kahungunu, Te Rarawa). In the video, dancers paraded around the whare in clothing made not only by Lissy and Rudi, but also Lissy’s late father, designer Colin Cole. The movement was fluid and each dancer seemed to curve into one another naturally. Funnily enough, the film reminded me of a pumping wharekai and the ways I’ve seen my nannies, koroua, aunties and uncles bend and bow around each other – all in sync, but also all holding their own space and mana in the heat of it all. Like Wharenui Harikoa, I felt the film referenced our ever-present connection and acknowledgement, as Māori, of whakapapa and taonga tuku iho.

As a craft form, crochet evokes memories of days spent sitting alongside kaumātua knitting, with cousins huddled under old crochet blankets and parcels of tiny beanies to new babies and first-time parents. My grandmother has crocheted something for everyone in our whānau over the years. Whether it be slippers, blankets or even dolls, everyone has something from Nanny Rose and her looping fingers. Like Lissy, my Nanny uses her hands to create intergenerational connections and ties back to herself that we can treasure forever.

I remember reading an article by Nadine Anne Hura (Ngāti Hine, Ngāpuhi) that talked about the physicality and love that goes into knitting and crochet. For her, creating these physical items that often lie around family homesteads and at our marae, are the perfect output of joy, grief and everything in between. It led me to think that this is probably the case for lots of our whānau who crochet and make things for others. Those slippers, blankets and dolls, like pounamu or rongoā, thenbecome taonga tuku iho, treasures passed down.

Wharenui Harikoa is an extremely ambitious project. Building any wharenui is one of those things we know people are capable of, but exactly how they do it is another story. To create a wharenui using wool and crochet is a huge undertaking. One shudders at the thought of the process and logistics that are involved. Lissy and Rudi’s wharenui is a trailblazing feat – no one has ever done anything like it before, making it both daunting and incredibly moving. It truly is a wharenui of te ao hurihuri.

Lissy Cole crocheting. Photographer: Ralph Brown. Supplied/Waikato Museum

For Māori, the concept of a whare extends beyond simply its common English translation of a ‘house’. A place of shelter is oftentimes a plethora of things held together by the people and essences that travel through it. Houses and homes worldwide hold significance, personalised by our cultural values, tastes and practices.

Our very first home, te whare tangata, is the womb. As Māori we understand through our pūrākau and whakapapa that the whare tangata is the meeting place of all things. Here is where death turns to life. We rest, we grow, we share, we take, we do many things within the warm buoyancy of this whare, all before even witnessing the first light, te ao mārama – it’s all pretty neat.

We’ve lived, and continue to live and interact, in all sorts of structures. For example, I often think about how my tīpuna would react if I were to show them my Mum’s swanky apartment at the base of Maungawhau. Back home, our marae Te Rehu is orange and green rather than the classic marae burgundy red. Just the other day I was scrolling through TikTok and found a Māori couple living in a glamp-core-yute off-grid which resembled something from those black and white pictures taken of Maungapōhatu during the times of Rua Kēnana. Māori are constantly in an āwhiowhio, or cycle of sorts. Wharenui Harikoa is a part of this cycle in the way it intersects traditional wharenui, made with natural elements, with the needs and accessibility of our communities across Aotearoa and beyond. Anyone can visit Wharenui Harikoa and anyone can connect with its expression of Indigenous joy.

Wharenui Harikoa details. Photo credit: Briar Pomana

Taking a moment to reflect on how far our mahi toi has come over the last 50 years, I am reminded of the Māori renaissance of the 1980s – a time that was rife with exploration, elasticated boundaries and Māori innovation. It was also a heavily political time that accelerated the pace in which work was produced and experienced. When I think of Māori art in the 1980s, and subsequently thereafter, names like Barry Barclay, Merata Mita and Witi Ihimaera spring to mind. People who added to culture rather than borrowing from it.

I think of how easy it is now for us to access incredible art and work from people on the same wavelength as those aforementioned. It takes less than ten taps of my fingers on a screen to summon work from today such as Wharenui Harikoa. I can keep close tabs on my favourite artists and befriend them, creating community and a collective experience from anywhere at any given moment. Which I choose to recognise as an amazing feat for our people. I have made so many friends over the internet that I would have never had the opportunity to meet otherwise. It has expanded my world view and network, fast-tracking this incredible new millennium of ringatoi Māori and the universes they so generously build and share.

Kahu Kutia (Ngāi Tūhoe) has written about a concept called ‘astronesianism’. It is a term Kahu once used to describe futuristic dreaming through distinctly tangata whenua and Moana lenses, and takes reference from Afro-futurisms. Wharenui Harikoa is a perfect example of astronesianism, as it is a physical manifestation of years and years of dreaming, wānanga and kaupapa Māori. It takes learnings from our ancestors into a vivid dream-space that shows us new possibilities for Māori futures. It prompts us to remember that as Māori we are never alone, we are constantly in relation to those who’ve come before us and those who will come after us.

Wharenui Harikoa is whānau and whakapapa, it is aroha too big to comprehend, harnessed through manaakitanga and wānanga shared. It is our wildest imaginations as both tīpuna and mokopuna. It is what Indigenous dreams are made of.