When Justice is Gone, There's Always Force

The new Superman movie is a confused mess, but it did a great job of pointing out everything wrong with superhero narratives. Matt investigates whether 2013's Man of Steel is the hero we're looking for - and, if not, who is?

I’ve always had a soft spot for Superman, I guess because I’ve always wanted to be able to fly. Not in a cursory “Wouldn’t it be nice…?” way. In a way whereby questions of wind goggles and flocks of birds and overhead power lines become real pauses for thought. I went skydiving once and laughed all the way down. Twelve thousand feet. The instructor thought I was having a hysterical episode.

Liking Superman is currently out of vogue. He’s corny. He’s super-fast, super-strong, and has many tertiary powers too: laser and x-ray vision, ice breath, the full gamut. This strikes many people as unfair – how can dramatic action emerge from a character beyond impairment, who we know must always win the day? The answer to this concern – that Superman’s more than the sum of his powers, that he represents an ideal or set of ideals – is exactly the reason for his unpopularity. “Truth, Justice and the American Way” have never meant so little in an age of cascading coups, civil war, drone strikes and PRISM. Is Superman like America because he values all human life equally, or because he knows when you’re Googling yourself?

Both. Neither. In the first Christopher Reeve Superman movie, Lois Lane asks Superman what he stands for. Not skipping a beat, Reeve gives Superman’s anachronistic motto. The film came out shortly after the Watergate scandal broke, and Lois sardonically retorts “You'll be fighting every elected official in this country.” Yet that’s exactly what he never does.

You might object that superhero genre products are mere juvenile power trips, low forms of escapism, pornographies of violence. Why should Superman solve world hunger when he’s busy being every thirteen year old boy’s self-image? I’ll buy that. But Director Zach Snyder’s recent take on the franchise, Man of Steel, seems to want to be something more. From their earliest roots, the Superman comics were bluntly allegorical in the most simplistic ways – ‘Smallville,’ ‘Metropolis’ – and 2006’s Superman Returns introduced the Jesus metaphors with dad-God Jor-El sending his only son to a people he hoped to make better. Snyder, however, dials up the ham-fisted symbolism to 11.

The story begins on Krypton, where we discover citizens are purpose-built for their social roles, with it being implicit this has led to some sort of degeneracy. Also they have over-mined the planet’s core, and it will soon explode. Superman’s father steals the recipe for future people/drones and stores it inside Superman’s genome, then blasts him to Earth. This all takes about eighteen minutes, during which we’re slapped across the face by the twin spectres of holocaust and eugenics as well as a grab-bag of genetic modification, fascism, environmental collapse, Christian iconography, and stylistic references to The Matrix, Alien and Avatar. The Brave New World-esque planned society’s wilful naivety will have you muttering ‘too much alcohol in the test tube’ every time Michael Shannon appears onscreen. Eventually the rest of the movie happens.

It’s a grab-bag of ‘themes’ and ‘motifs’ that fail to cohere intelligently. You can’t have irreverence with hand-on-heart Jesus metaphors, Nietzschean philosophy with shrugging moral ambiguity. You try and have everything and your film turns into a bloated chimaera, less steel than slag.

[caption id="attachment_7668" align="aligncenter" width="500"] Courtesy Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal[/caption]

Much of the criticism the film’s copped centres on the wanton destruction that Superman visits on whatever unfortunate location he happens to be visiting. A 7/11, an International House of Pancakes, the Kent family house. After a truck’s gone through her roof, Clark Kent apologises to his mother for bringing vengeful maniacs home. “It’s only stuff, Clark. It can always be replaced.” The same cannot be said for the 129,000 people killed in Man of Steel’s climactic battle scene.

Confession: I liked the orgiastic destruction of that finale. Accidentally or not, Snyder’s movie gives us the most honest depiction of the hypocrisy that being Superman necessarily entails – the gulf between saving a busload of children and killing 129,000 people in a brawl with a fellow demi-god. Of course in this ‘gritty’ retelling of the Superman mythos (is ‘gritty’ simply film reviewer dog-whistle for ‘you won’t feel condescended to for enjoying this entertainment meant for children’?) people get massacred en-masse, even If the financial imperatives of an M-rated movie preclude almost any blood.

Superman actor Henry Cavill’s ludicrous anguished scream when he snaps antagonist Zod’s neck doesn’t quite let you forget that Superman was ultimately responsible for attracting the lebensraum-loving Kryptonians in the first place. Nor does his passionate kiss with Lois, as the ashes of what were recently her fellow citizens slowly settle around them.

People were angered and confused by these things. This was not a Superman we recognised. This man was amoral at best, wilfully negligent and unapproachable. He saves a soldier falling from a helicopter, and smashes General Zod through a building full of screaming office workers. He rescues Lois, and sacrifices a bustling city.

In a 2006 examination of Superman Returns, A.C. Grayling suggests:

In the 1930s his upholding of Truth and Justice coincided with Scarface Capone and the rest of the Prohibition-created criminal gangs which held Depression America to ransom. In the 1940s Truth and Justice were joined by the American Way as what Superman defended, during the war against Nazism and Japanese aggression. In the 1950s Superman fought battles against dastardly technologically-savvy super-villains, a straight Cold War theme. Later, and especially in the period since the Cold War ended, matters become merely personal: the task of pitting his brawn against the brains of Lex Luthor and Brainiac appeared to be independent of bigger questions.

When you have strength to outmatch Hercules, when you’re virtue made flesh, incorruptibility personified, what does it mean for matters to become ‘merely personal’? Superman doesn’t tackle the entrenched corruption or structural inequality that he has the raw power to change; catch as many diamond thieves as you like, smash as many aliens through gas stations as required, but that’s not going to stop kids going to bed hungry and growing up resentful. By helping maintain order he preserves a crappy status quo.

Not that he’s the only one. Batman has a better reputation than Superman: his back-story is more human in scale, and his compelling animus derives from his human flaws, his human intelligence, his human strength. Even so, crime in Christopher Nolan’s Dark Knight trilogy is treated as unproblematically as crime in Metropolis, despite taking place in a city so laden with grit you have to scrub your face after watching. Billionaire Bruce Wayne helps the police commissioner keep the peace against embittered undesirables, and the subtext of The Dark Knight Rises finds Batman fighting the Occupy movement. Indeed, the inherently fascist undertones of the Batman narrative were explored quite thoroughly by comic book writer and artist Frank Miller. A man of striking sexism and xenophobia, Miller’s work with Batman comics in the 80s and 2000s manifested a somewhat more awful Dark Knight than the one Nolan eventually reconfigured for a mainstream palate.

Snyder has insisted by dint of its ‘grittiness’, by its eschewing of campiness and most of all by its uncompromising seriousness that Man of Steel takes place in a world very much like our own. Near the beginning, Clark Kent takes a half-hearted stab at preventing sexual harassment in a bar where he’s working, but would Superman have flown to Austin, Texas, to berate the legislature for recently voting to curtail women’s autonomy? He saves oil rig workers from immolation, but does he stay to clean up the spill? Does he in any way attempt to make us a better species — more noble, sage or introspective? Is 2013’s man of steel the superhero we’re looking for?

I would argue not. I would argue that Superman represents a thoroughgoing iconoclasm he consistently fails to live up to, because Superman’s canon is a dogma of squandered potential, and it took a bollocks film to point that out.

There’s this scene with Clark Kent halfway through the movie. He’s young, and he’s crying to his dad. “Did God do this to me?” he asks. Wouldn’t it have been great if instead of showing him a crashed space ship, his dad had simply shrugged and said “Maybe?”

The best recent versions of the Superman story have been the ones that modified the staid formula. In the three-issue Superman: Red Son, Kal-El crash lands in the Ukraine instead of Kansas, and is raised by Russian peasants. Tiring of the Cold War he’s forced to invigilate, he ascends to power, creates a harmonious USSR, and eventually peacefully conquers the world. He makes sure all the humans under his care are looked after, but eventually realises he’s robbed them of intentionality and self-determination, the qualities he sees as being fundamentally human: he has essentially become a glorified zoo-keeper. It’s a skilful exploration of the responsibilities and consequences of unlimited benign power, and is vastly more interesting than watching Superman steal pants and a jacket from the unlocked car of a destitute family (yes).

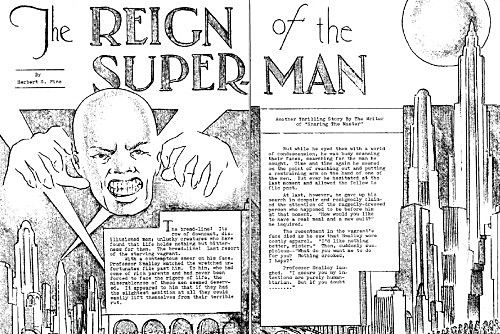

Further back, Superman couldn’t fly. In fact, he wasn’t from Krypton. Actually, he wasn’t even a good guy. In The Reign of the Super-Man, published in 1933, Jerry Siegel imagines a different sort of Superman to the more recognisable one he’d go on to create later that same year. This Super Man is the creation of a malevolent chemist who experiments on human subjects by pulling them out of Great Depression-era breadlines and promising them fine clothes and something to eat. Given tincture of comet, this Super Man gains telepathic powers, kills the scientist, and seeks to dominate the planet – until his powers run out and he’s forced back into the breadline. But you know? I’d take even a classic hubris tale over John Kent insisting that his son let the bus full of children drown next time (also yes).

The Superman of 2013 – and earlier – ostensibly stands for a whole lot of values, reifies them, but doesn’t deploy them. Postmodern performance artist Laurie Anderson’s O Superman presciently invokes our hero to represent the hollow ubiquity of consumerism, the implicit violence of globalisation, and the misdirected potency of US foreign policy:

Somehow it got to number two on the UK charts, but then even Man of Steel has made back nearly three times its budget, and the DVDs aren’t even out.

So Superman has become worse than tired and predictable – he has become an agent of oppression. It didn’t have to be this way. The graphic novel Watchmen was a glorified comic book that broke all the conventions of comic books, a new creature that mocked them by becoming something innovative, not locked like Superman in the undead stasis of convention. It was a story of human and inhuman frailty, cold war tension and resentment in the face of overwhelming, alien power. The superman of Watchmen, Dr. Manhattan, doesn’t have a motto. He didn’t even have a sigil until a talk-show host convinces him he needs one to self-market. He struggles to find a place for himself within the societies of puny humankind, but can’t, and leaves. Doesn’t this feel more honest than truth or justice? Doesn’t even this alien power feel more human than the American Way?

Coincidentally, Snyder directed an adaptation of that graphic novel. The movie he made was about nuclear power, I think – or perhaps nothing at all. There were a terrific number of explosions. Hollywood reduces, sure. But in Man of Steel’s case, it didn’t have a whole lot to boil off. It’s intriguing Christopher Nolan agreed to be Executive Producer. In Keanu Reeves’s documentary on the emergent impact of digital cinematography, Side By Side, he admits to loathing digital cameras and CGI effects, but that’s almost all Man of Steel is. It’s doubly mystifying considering the Batman/Superman crossover film that’s just been announced for 2015, with Nolan again playing Executive Producer.

Nobody in Watchmen did the flying thing, but Dr. Manhattan teleported around pretty regularly, and I guess I’ve got a soft spot for that particular superpower. It raises certain questions. What if one were to teleport into a solid wall, or a person? What happens to the air one displaces? What if you’re handcuffed to something? It’s enough to give one pause for thought.