Why We're Not Popping Up

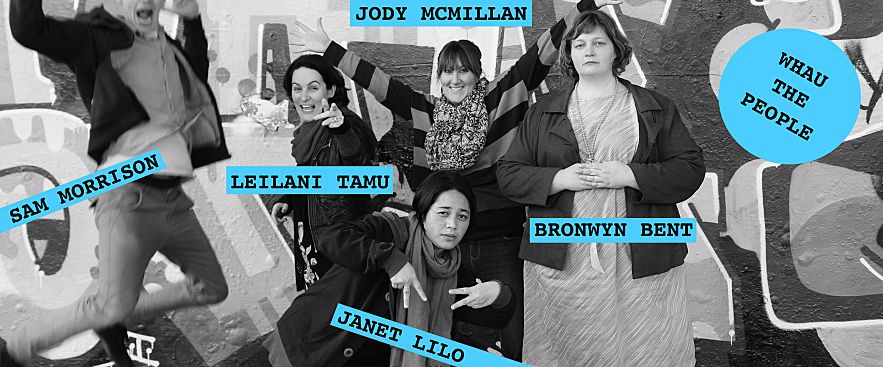

Whau the People on why pop-ups aren't enough if you want to build a community.

Whau the People on why pop-ups aren't enough if you want to build a community.

When we started our little collective in Avondale a few years ago, we weren’t sure what we were going to to do, just that we thought we could run some cool projects around the area we lived in, which has a lot of people doing creative things but not many places to do it in. One of our guiding principles was that we didn’t want to have to always leave the area to take part in various arts activities. However, without any sort of space, local activities would always have to be in temporary pop-up spaces. That’s exciting in lots of ways, but we also realised that to realise more complex, longer-term projects, having some sort of more permanent space would be necessary.

There’s nothing inherently wrong with a pop-up space, and in fact, there’s a lot right with them. There’s great value in using otherwise abandoned spaces for something positive. Who wouldn’t rather have a temporary gallery than a derelict shop?

Pop-up spaces lend an air of excitement to the otherwise relatively ordinary. In a world where we’ve seen it all before, there's inherent novelty in seeing something where there’s usually nothing is immensely attractive. They can also help us see both art and the environment in a different way; this is no longer a takeaway bar, but a gallery; no longer a sterile installation but something to clamber on and play with. There’s lots of people who feel like they can’t walk into an art space (obviously that’s a whole other big issue), but will happily interact with something in a space they’re more familiar with, and that’s another good, compelling reason to use the pop-up model.

As individuals and as a collective, we’ve worked in all sorts of temporary spaces, including empty lots, strip parlours, and shops having a last hurrah before demolition. Apart from the common factor of them being places art projects don’t usually happen in, they’re also sites that need a great deal of work put into them before anyone can even think about the art, as Lana Lopesi wrote about recently. The empty lot required six days of 20 people sweeping, picking up rubbish and weeding to make it safe for people to be in.

None of this work is apparent for anyone viewing the final presentation, nor does it need to be, but it impacts the work in many ways. An empty space is precisely that. Everything else required for a project to happen in there has to be thought about, borrowed or purchased. This means, in the typically time-and-budget-pressured environment that most arts projects operate in, that less time and thought might be going into the creation of what is actually meant to be on show. Every day spent on finding chairs for a space is one less day spent on making the art.

Every day spent on finding chairs for a space is one less day spent on making the art.

Apart from the logistical challenges of the pop-up space, there’s a more ideological concern around the creeping official enthusiasm for the pop-up space. In our part of Auckland, there isn’t a single public art space - and very few private ones - from Ponsonby through to Titirangi, a geographic area that takes in much of the central-west of the city, and tens of thousands of people. The Avondale community centre languishes, half of it boarded off for four years due to black mould, and the rest of it like a relic from ghost town, the doors only opening once or twice a day when the automated system (run from a central office) opens them for a booking. Encouraging the use of temporary spaces over more permanent ones distracts from the fact that the former are only needed when the latter aren’t there. It’s no coincidence that the rise in pop-up spaces occurred after the global financial crisis hit, and public authorities and other community groups withdrew from committing money from big infrastructural projects. Apparently pop-up spaces are very big in Athens right now.

Encouraging the use of temporary spaces over more permanent ones distracts from the fact that the former are only needed when the latter aren’t there.

It’s understandable that in straitened times, the cheaper pop-up space is preferred, but it’s frustrating that there’s little middle ground between the pop-up and the massive bricks-and-mortar projects. This is further complicated by arts projects usually being seen as non-essential; with all of these complications and pressures on budgets, of course the pop-up often wins.

In communities like Avondale (high on the deprivation index, albeit gentrifying), there’s already an awful lot of popping-up, although it’s not usually called that. It’s more commonly known as a business failing. Shops open and close with regularity, and not usually on purpose. One large empty shop is still littered with stock left behind from a hasty exit ten months ago, and the owners of the new “natural supplement” shop confessed they were only there until they could move to a more desirable neighbouring suburb. In places like this (and there are plenty of them in New Zealand) setting up a longer-term space becomes about more than just providing a space for longer than a week at a time; it’s also saying: we can do this. We can make a space that isn’t just waiting for the next best thing to come along, or to move up the property ladder into a “better” area.

Which is why we’ve just opened a new aspirationally-permanent space, All Goods. It’s in a former bank, right in the middle of a shopping strip. Yes, it’s got all the hallmarks of a pop-up space, but we’re taking a different approach, thinking about what we can do there next year, and the year after that. Having a more permanent home allows people to think differently about what’s possible; after only having the keys for it for a few weeks, we’ve already had more people talk about projects they’d like to do there than in the previous two years of us doing projects in in temporary spaces.

Ultimately, a pop-up space is like going camping: usually good fun, a cheap way to have a new experience and to enjoy a new environment, and something we’re appreciative of. Over the two years of our existence, we’ve used pop-up spaces for our two arts festivals, which have featured everything from bonsai art through to tattooing through to pipe bands. We’ve also spent two months presenting various art projects at the Avondale Market, and run a short-lived gallery space in a shoe shop window. All of these projects have been satisfying, but because of their temporary nature, haven’t been able to build up longer term commitment, from both artists and audiences. It’s for this reason we’re moving into a more permanent space: one where we can invite people to be in, feel a part of, and have a stake in: a home, rather than a tent.

Whau the People are currently raising funds to run a neighbourhood arts space in Avondale, Auckland that will be a hub for all sorts of creative activities from bonsai through to painting through to karaoke. Support them here