Tender Raunch: A Conversation with Laura Borrowdale about Aotearotica

Sarah Jane Barnett talks to Aotearotica editor, Laura Borrowdale.

Laura Borrowdale is the founding editor of Aotearotica, an erotica journal that aims to represent all genders and sexalities. As a preamble to Laura's session at LitCrawl, Sarah Jane Barnett talked to her about what it means to be sex positive, and how poor grammar is a real turn off.

Sarah Jane Barnett: I really enjoyed Aotearotica. This issue is volume three, so is that three years now? What made you want to start the journal?

Laura Borrowdale: Ah, three years sounds like a vast expanse of luxurious time. We hit the ground running and we’ve put out a volume every six months or so. We’re actually scheduling volume four to go on sale in early December. Which is crazy, when I think about it.

I started the journal after writing a piece that was too explicit for the mainstream, but too literary to run as smut. I got a bit no. 8 wire about it and just decided I could do it myself. So I did. There was about a week from when I decided to do it to when the Creative Communities Scheme funding application was due, so there was no time to doubt what I was doing.

SJB: Aotearotica states that it is ‘sex positive’ – what does that mean to you beyond representing, as your website says, ‘all genders, sexualities and perspectives’? I ask this because you live in Christchurch, which is where I grew up. From my experience, Christchurch is not the most sex positive city in Aotearoa. Maybe this has changed and I’m being hard on my ol’ home town. New Zealanders aren’t known for being sex positive though, even if we statistically have a lot of sex. For me, being ‘sex positive’ means engaging my curiosity before my judgement when it comes to sex. How about you?

We view sex as a positive experience, or one that is intended to be so. The goal is to celebrate it.

LB: We view sex as a positive experience, or one that is intended to be so. The goal is to celebrate it, and to provide for a community of people who all experience things in different, equally valid ways. Sex in our culture is so often focused on the hyper-sexualised, or on the negative, exploitative experiences, and we thought, hey, where’s the stuff we get to enjoy without hurting anyone? Where’s the healthy fun stuff?

I wrote for VICE recently about how, although we have a lot of sex, New Zealanders don’t necessarily have very good sex. And why would we? We don’t talk about it, unless we belong to niche communities, and we really should.

SJB: Even with our Puritan roots, I think New Zealanders write well about sex. Do you have any favourite Aotearoa authors when it comes to erotica? The last sexy book that I really loved was Tess by Kirsten McDougall. It’s the sort of book that I needed as a teen when learning about my sexuality. In terms of defining erotica, do you make a distinction between a story or poem that has sex in it, and one that has the explicit purpose of arousal? And what makes you want to publish a piece of writing?

LB: Gosh, that’s a full packet of questions there, SJB. We take a really broad definition of erotica. A lot of the writing we publish isn’t necessarily intended to arouse (on the other hand, a lot is), but more to provoke thought. Which, in our opinion, is pretty sexy.

In terms of New Zealand authors, there was one poem that was really pivotal to my thinking about writing about sex. It made me realise that everyone has this kind of thing tucked away; and once you’re aware of it, it runs through so much work; we collect it explicitly in Aotearotica but it’s everywhere, really. It was a poem by Bernadette Hall, called ‘Go Easy, Sweetheart.’ She describes a little girl creaming butter and sugar and then the poem changes and she says:

Go easy,

sweetheart. Little bubbles exploding soft

like years later when he licks and licks and little

bomb blasts like pain that must be entered

into, like delight…

I've loved that poem for years. It’s the kind of thing you could write down and post to a lover. And I worry that we've lost that with modern poetry, that it has become more about the poet’s cleverness and less about the response of the ordinary reader. I hope that Aotearotica might be the kind of publication that you would want to share with someone else.

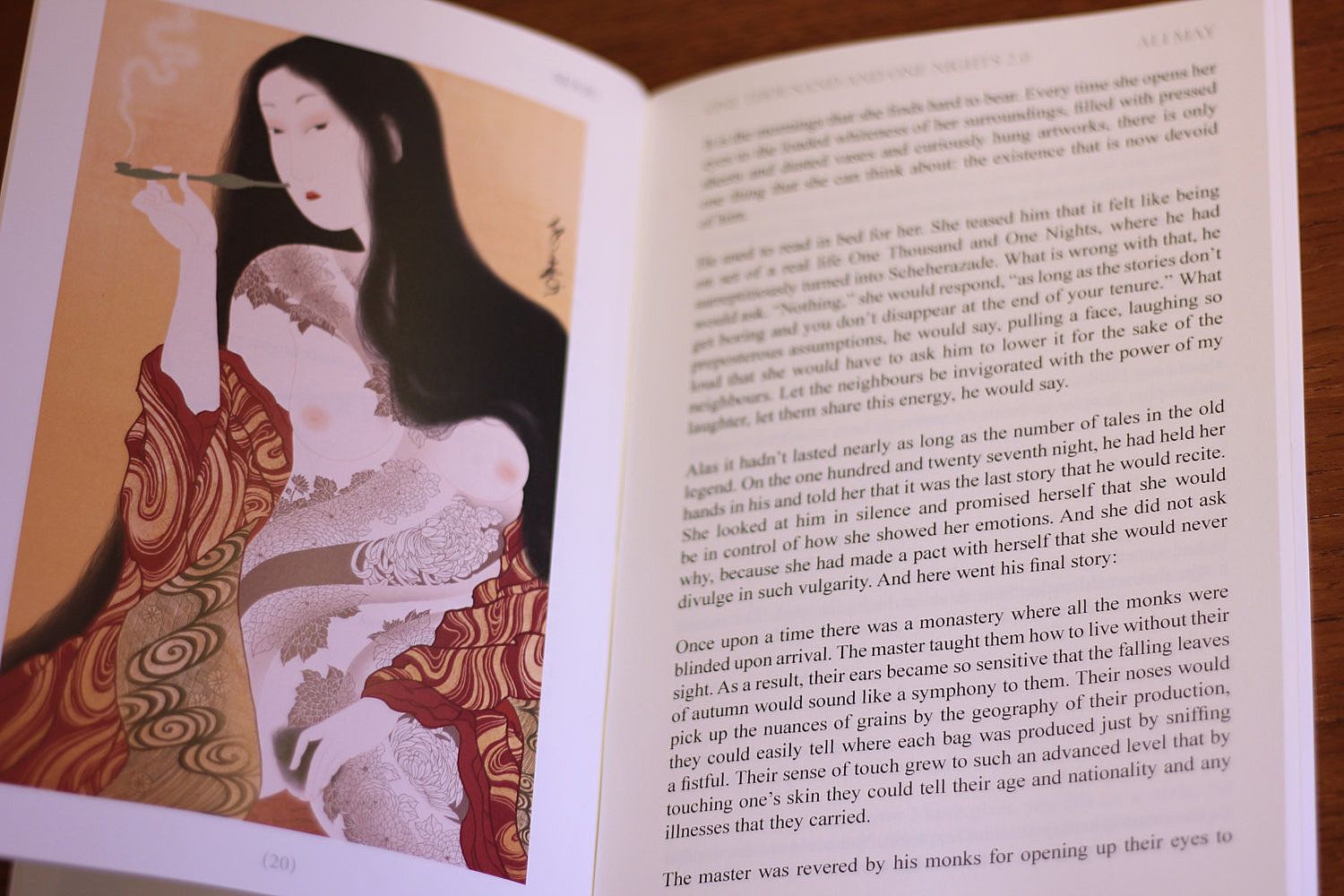

SJB: The journal mixes illustrations and writing, and I take my hat off to your visual editor, Oliver Rabbett. He’s got an amazing eye. As he says, ‘clean lines, minimalist design and a wee bit of raunch.’ Can you talk about how you wanted the visual art to interplay with the writing? I found it one of the most affecting (read: titillating) parts of the journal.

LB: We have to work really closely together on the art and the writing; I feel terrible about the micromanaging he’s subjected to. There’s an important interplay between the writing and the imagery that we select too, and we try to use that relationship to bring elements of each piece to the fore, to twist or reinforce the reader’s perception of both. Our Instagram has been pretty instrumental in that…we have over 140,000 followers so a call for submissions results in us being completely swamped. Our authors are primarily New Zealanders, or people who have a connection to Aotearoa, but I wish we got more New Zealand art.

SJB: I did notice that your Instagram feed mostly features white, able-bodied and thin-bodied people, although the notable exceptions suggest the choice is not purposeful but imposed. Is non-white/able-bodied/thin-bodied erotica harder to find because we live in a society that promotes that as the ideal?

LB: Yeah, Instagram is a problem. It’s given us exposure that we’d have never had otherwise but it blew up, with thousands of followers in a very short space of time. We’re big in South America, and Tehran, strangely, and the dynamic between what we post and what gets a reaction troubles me. As you say, the cis, het, white, conventional imagery will get four to five thousand likes, and something celebrating trans bodies will get one thousand. Something with gay men will require heavy policing of the comments.

I try to source images that provide alternative perspectives, but we are limited in what gets submitted and fits our aesthetic. Because we are big, and have attracted some conservative elements in our audience, anything not heterosexual is reported and disproportionately taken down by Instagram. It's a struggle to be as diverse as our physical publication is, and as diverse as we’d like it to be.

Instagram is a problem...the cis, het, white, conventional imagery will get four to five thousand likes, and something celebrating trans bodies will get one thousand.

SJB: At the New Zealand Young Writers Festival earlier this year you chaired a session with our editor in chief, Lana Lopesi, and author Karen Healey about the presentation of sex and sexuality in erotica, critical writing and fiction. That must have been amazing – I wish I’d been there! Did you come to any conclusions during the session? Let us pick your brain.

LB: I loved that session. I got a lengthy email the day after from someone who had been there, in which he helpfully explained to me just what it was that we’d said and discussed. I mean, it was awesome he took so much away, and also hilarious that he took so little.

It was a real indulgence, having these two inspiring women to talk to. I was struck, as I was prepping the session, just how pervasive this topic is, that I can talk to an essayist and a YA writer about the same things. And that I needed to. But at the same time, it felt pretty wonderful to realise that we were all coming at the same goal from different points.

SJB: I realised that the journal has been sitting on my dining table all week. I didn’t think twice about this, but then I live in a household with Hera Lindsay Bird’s ‘Bisexuality’ poem on the wall, as well as a cross-stitched vulva. That said, if I owned a copy of Playboy I wouldn’t leave that on the dining table.

LB: We wanted that. We really consciously designed something that you’d leave on your coffee table if your mum was coming over, or that you wouldn’t feel embarrassed carrying up to the counter in a book shop. A lot of our purpose is around normalising and de-stigmatising healthy, happy sex and gender expression, and the design is very purposeful to that end.

Erotica...acts as a catalyst for the imagination, rather than replacing the audience’s imagination.

SJB: I know you’ve been asked this before, but can we talk porn versus erotica. In one interview you said ‘pornography is generic, erotica is very specific’ and that ‘pornography for me is about bodies, and erotica is about people.’ I really dig this distinction. I don’t think that we need to fully rehash why porn can be problematic (dehumanising objectification; exploitation; consent issues), and I am not someone who is anti-porn. There is a lot of fantastic amateur or feminist porn out there that serves a purpose. What do you see as the purpose of erotica beyond arousal – what does it do for someone that porn doesn’t?

LB: Isn’t it the same as the difference between reading the book versus seeing the movie? There are favourite books of mine that I refuse to watch the (by all accounts) amazing adaptations of, like The Handmaid’s Tale, because the original had such a powerful effect on me. Losing my interpretation to someone else’s isn’t something I would risk with those stories. Erotica is the same, whether it’s visual or written. The best kind acts as a catalyst for the imagination, rather than replacing the audience’s imagination.

SJB: From reading interviews and the journal, Aotearotica has political goals as well as erotic. Tell us about those.

LB: I think it is that our erotic goals are motivated by our political ones. Our choices around the kinds of erotica we are interested in are a reflection of the feminist, pro-sex, LBGTQIA+ inclusive politics we subscribe to as an entity. We love things that blur the edges a little.

Also, I’m a teacher. I’m painfully aware of the fact that young people can have a very distorted view of what a positive sexual experience is or could be. It wasn’t enough for me to just condemn the treatment and sexualisation of women and minorities in the media, I felt like I needed to make an effort to actually provide an alternative to the culture I saw as problematic. This isn’t a publication for under 18s, but it’s a step towards shifting the culture they grow up into.

I felt like I needed to make an effort to actually provide an alternative to the culture I saw as problematic.

SJB: You write your own erotica as well as editing Aotearotica. What sort of erotic themes or characters do you like to write about?

LB: I like things that are unexpected, or provide a juxtaposition. The piece I wrote first, the piece that started the journal, is a short story comparing a character’s sense of oblivion and release during oral sex to her experience of night swimming and the imagined feeling of a shark attack. I promise it was sexier than that sounds. I’m interested in what happens in people’s heads when they are engaged with their bodies.

SJB: You’ve got a session during phase three of LitCrawl 2017. Tell us about what you’ve got planned. Are we all going to leave turned on?

LB: Actually, I think the work in that particular session is more tender than anything else. There are some especially lovely graphic works by Dylan Horrocks and Sarah Laing being shown. Monica and I are reading prose. But I think you’ll leave wanting to be close to someone.

SJB: You’ve said, ‘I don't think there's any faster turn off than poor grammar or clunky description.’ Don’t you think that's true for life as well as erotica?

LB: Don’t you? Have you tried dating in the age of texting? I mean, I’m being facetious but it’s hard to be turned on if you’re distracted. It’s hard to engage if there are irrelevancies demanding your attention. But, then again, welcome to the modern era.

Laura Borrowdale appears in Phase Three of LitCrawl, Saturday 11 November. See our full picks here. Feature image: 'Please keep me in mind' by Cinocefalo.