A Lonely Life: At the Threshold of the World

Max Harris reviews Olivia Laing's new book, The Lonely City: Adventures in the Art of Being Alone, and wonders why we don't consider loneliness when formulating the very policies that could help challenge it.

Every now and then – as I’m walking down the street, or at a party in the early hours of the morning, or in a university seminar – a chill runs through my body, and I feel acutely alone in the world. I’m numb, just fleetingly. It’s as if my reserves of warmth have been suddenly sucked out. In these moments, it doesn’t matter that I have a wide network of friends or acquaintances or a busy social schedule. I feel lonely.

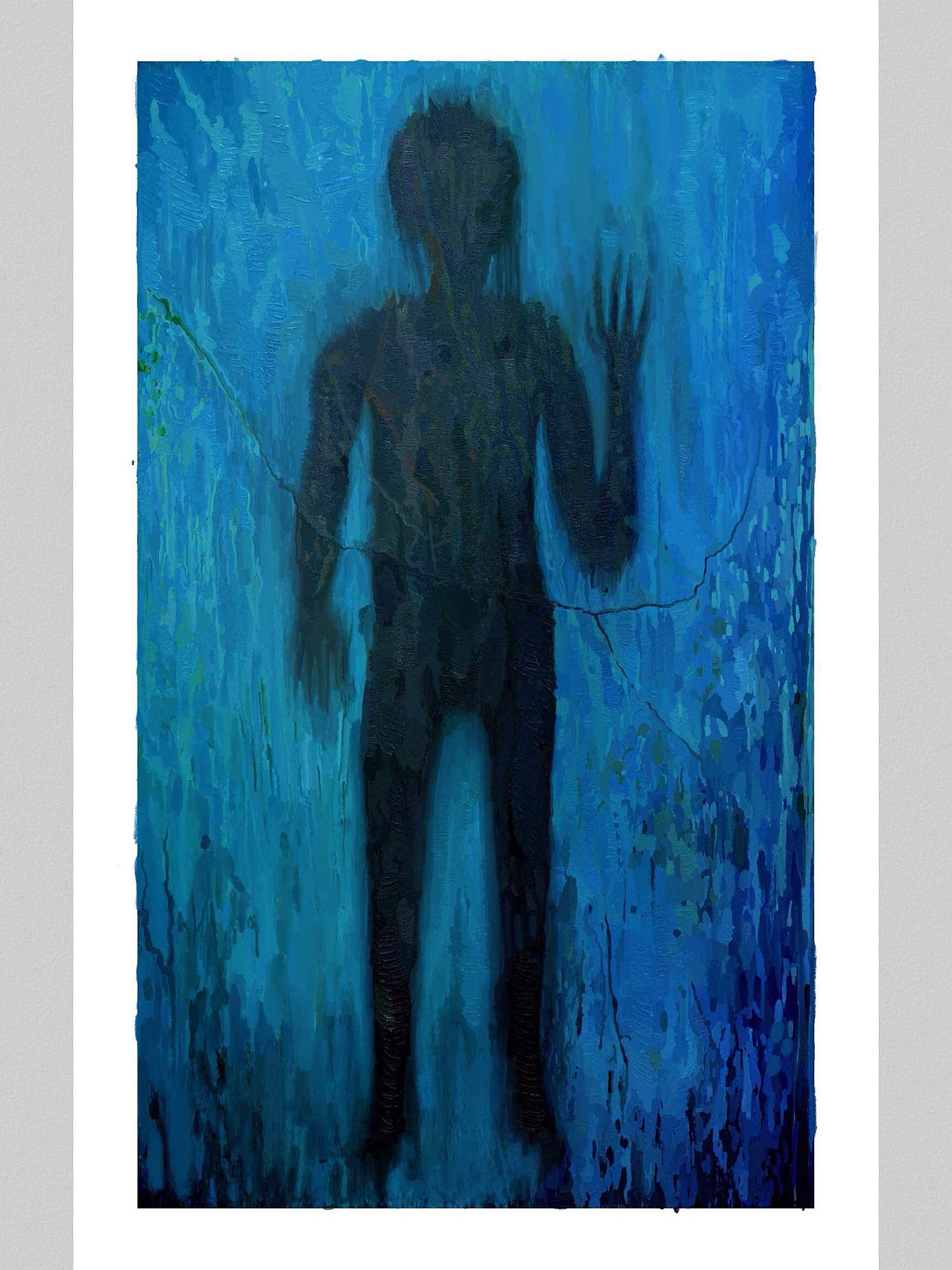

In Beyond Good and Evil, Nietzsche says his heart cannot bear these “iciest shivers of solitude”. In her new book, The Lonely City: Adventures in the Art of Being Alone, Olivia Laing describes the experience in a similar way. She talks on the first page about the “tremor of loneliness” that a person can feel when standing at a window looking out on a busy urban street. Later, she says loneliness is like being “encased in ice.”

“I don’t want to be alone,” she writes in the second chapter. “I want someone to want me. I’m lonely. I’m scared. I need to be loved, to be touched, to be held.”*

Laing’s book is a reflection on loneliness and how we deal with it. Laing finds herself adrift in New York, having travelled there for a relationship only for that relationship to fall apart. Alone in an apartment, she spends time sprawled on a couch, scrolling aimlessly through Facebook and Twitter.

Loneliness is a “shameful and alarming” feeling, Laing tells us later in the book, a feeling with physical consequences. Once loneliness has set in, people can experience the world negatively, setting a “grim cascade into motion” where the lonely person becomes increasingly suspicious, withdrawn, and isolated. The severity of loneliness varies with person and context, ranging “from discomfort to chronic, unbearable pain”.

She traces multiple possible causes over the course of the book, including insufficient attachment and physical contact in infancy, loss (a cousin of loneliness) and bereavement, the societal policing of those who are strange and the desire for wholeness. What makes loneliness especially painful is that it’s often incommunicable, and that it can only be addressed by building intimate relationships, which might be cripplingly difficult for those who already feel lonely.

Laing explores how loneliness reflects paradoxical feelings about others in society: it can involve at once a desire to be apart from people and a desire to be intimate with others. This is the condition of the lonely, for Laing: an uncertain relationship between the self and the other, or between the self and the outside world.

Laing’s drawn, in this period, to figures in the world of the arts who have lived lonely in New York and elsewhere. These people are cut off from the community around them in different ways. There’s Edward Hopper, who appears in photographs as a person wary of contact. Hopper resisted speech, and accepted only late in his career that he was “probably … a lonely one” – a statement, as Laing observes, that hints at the possibility of being in a community of lonely people.

Then there’s Andy Warhol, also uncomfortable with speech, who was led by a fascination with meaningful conversation to capture over 4,000 audio tape recordings of conversations with others. Warhol rejected the pull towards being the same as others – and he was, throughout his life and career, “hungry for company but ambivalent about contact”. He lingered, Laing says, “at the threshold” of the world.

It’s as if my reserves of warmth have been suddenly sucked out.

Like Warhol, David Wojnarowicz brought a camera between himself and others, in part to cover over difficulties in communication. As with Hopper and Warhol, Wojnarowicz felt a gap between him and others open as he grew older – a gap he bridged through art and sex. “[M]y queerness”, he wrote, “was a wedge that was slowly separating me from a sick society”.

Henry Darger is the most isolated of the main figures sketched by Laing, and the only one not to have lived in New York (though much of his work is now archived there). Late in his reclusive life, a series of mostly fantastical artworks and writings were uncovered in the boarding house where he lived in a working-class region of Chicago. Darger had shared none, or very little, of this with others.

Laing turns her attention, finally, to Klaus Nomi, a German immigrant to New York who achieved success in the music world in the 1970s and 1980s. Just as Warhol played up the distinctive qualities of his body, so too Nomi flaunted his delicate features. Nomi longed for love. In the early 1980s, he was diagnosed with AIDS and was approached with extreme caution even by close friends at a time of paranoia about the disease.

All the central individuals in the book are men, but Laing’s attentive to the gendered dimension of loneliness: she explores, for example, the different pressures and feelings faced by women alone in their 30s. (She also writes strongly about the way in which the Chelsea piers, frequented by Wojnarowicz, were a more uncomfortable place for women than they were for men.)

Moreover, Laing’s fascinated by a host of other people who swirled around Hopper, Warhol, Wojnarowicz, Darger, and Nomi. When discussing Warhol, Laing makes an extended detour to explore the life of Valerie Solanos, a friend of Warhol’s who tried to shoot him in 1968. Laing’s investigation of David Wojnarowicz leads her to Greta Garbo, who strode through New York City for five decades from the 1940s on, hoping to be “left alone”. Laing even touches on Garbo’s stalker-paparrazo, Ted Leyson, who spent eleven years photographing Garbo, with “a kind of gaze that whether given or withheld is dehumanizing, a meat-making of a profoundly unliberating kind”.

In the penultimate chapter, Laing considers Josh Harris, a young internet entrepreneur dubbed “the Warhol of the Web”, who experimented with different participatory projects in which people’s ordinary actions were surveilled and watched by people online. These projects, somewhere between The Truman Show (which they predated) and the Stanford prison experiment, included a documentary filming Harris and his girlfriend Tanya for 100 days, which resulted only in a “humiliating public separation”.

Other figures that become the subject of Laing’s drifting curiosity over the course of the book include science fiction writer Samuel Delaney (who, like David Wojnarowicz, spent time cruising the Chelsea piers), photographer Nan Goldin (whose photographs of touch, intimacy, and sex are described as at once rebellious and tender), and Peter Hujar (another photographer, who knew Warhol, Goldin and Wojnarowicz, and died of AIDS in the 1980s).

Distinguishing loneliness from solitude, Laing observes that we can be lonely among other people.

Laing writes of Hujar that he “looked at his subjects with the eye of an equal, a fellow citizen”. The same can be said of Laing in The Lonely City. While she’s occasionally critical (especially of Garbo’s stalker Ted Leyson, and Josh Harris), she almost always aspires to understand and empathise, following with care the arc of her subjects’ lives and legacies. She threads personal reflections and digressions through the narrative, always willing to reveal vulnerability, never keen to project the artificial sense of cool found in some books set in contemporary New York.

Laing admires the artists at the core of the book for unashamedly expressing their needs, and she too is unflinching in articulating her own needs. She speaks bravely of her mother’s experiences “deep in the closet”, and her own worries about being “insufficiently desirable”. Distinguishing loneliness from solitude, Laing observes that we can be lonely among other people. And she’s slow to dismiss it as an entirely negative phenomenon: “I don’t think any experience so much a part of our common shared lives,” she writes, “can be entirely devoid of meaning, without a richness and a value of some kind.” “Loneliness,” in the words of the Dennis Wilson song ‘Pacific Ocean Blue’, “is a very special place.”

Only occasionally does the book’s style strike a slightly discordant note, as when she describes Warhol’s belief that he had a responsibility to rein in Jean-Michel Basquiat as “of a piece” with Warhol’s pop-coloured Extinction silkscreens of imperilled species, such as an elephant, a rhino, and a ram. Though Laing clearly doesn’t mean to compare Basquiat directly with these animals and shows an acute awareness of the racial prejudice faced by Basquiat, the passage could reasonably read as making such a comparison – and to this extent it lacks her usual sensitivity. But generally, this is a humane, funny, powerful book. Laing writes admiringly of Maggie Nelson in The Lonely City, and Laing’s writing shares many of the qualities found in Nelson’s The Argonauts. Like Nelson, Laing deftly weaves together complex academic work and personal narrative, and reveals idiosyncrasies while remaining an eminently relatable narrator.

David Wojnarowicz is quoted in the book as saying: “To make the private into something public is an act that has terrific repercussions on the pre-invented world”, where the “pre-invented world” is the world we have inherited with all of its problems and prejudices. Laing, by making her private experiences of loneliness into something public in the form of The Lonely City, has produced a work that should have terrific repercussions on our pre-invented world – on our world of anxiety and inhibition.

*

As well as exploring what loneliness is, the book loops around how we try to deal with it. A key coping mechanism that Laing explores is creative activity – the act of writing or producing art that aims to externalise feelings of loneliness. Pushing negative feelings onto the page or the canvas doesn’t just expel these feelings (albeit sometimes only temporarily). It also helps create coherence where it doesn’t seem to exist within a person’s thinking, and can open up the possibility of other people finding commonality in these feelings. Art can be a way to “put the put the broken pieces” of the self “back together”, Laing tells us when discussing Henry Darger. Words were, for Valerie Solanos, “the flung rope between her and the world”.

Activism can play a similar role, and Laing hints at this when describing David Wojnarowicz’s involvement with ACT UP (the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power), and Wojnarowicz’s efforts “to make public the truths of his own life”. In Close to the Knives, Wojnarowicz wrote: “To place an object or writing that contains what is invisible because of legislation or social taboo into an environment outside myself makes me feel not so alone; it keeps me company by virtue of its existence. … [T]he work can … act like that ‘magnet’ to attract others who carry this enforced silence.” Seeking out fame – Warhol’s fifteen minutes, or Josh Harris’s projection of personal experiences online – is another version of this impulse.

Finally, Laing says that finding a community of other lonely people is a way of addressing loneliness. This strategy proves fruitful for Laing herself. Carefully chosen images are interspersed through the book, highlighting the community that Laing has created around her – and she notes that one of the images of Warhol, a painting by Alice Neel of him half-naked, with eyes shut and one arm cradled behind his neck, “was one of the things that most medicated my own feelings of loneliness”. Laing writes at the end of the book:

The way I recovered a sense of wholeness was not by meeting someone or by falling in love, but rather by handling the things that other people had made, slowly absorbing by way of this contact the fact that loneliness, longing, does not mean one has failed, but simply that one is alive.

This is ‘the city’ of the book’s title: the population of lonely people that came to form Laing’s context in New York. Through writing her book, Laing is also attempting to provide that community, that city, for others who need it. The Lonely City’s epigraph reads: “If you’re lonely, this one’s for you.”

Reading Olivia Laing’s book did have the effect of making me feel less alone, even if only for a few days. It struck upon aspects of loneliness that chime with features of my life. My physical awkwardness has something to do with my occasional feelings of loneliness, I’m sure: I’m a little gangly, with a slightly indented chest, and flat feet. My 2014 diagnosis with Loeys-Dietz Syndrome, a rare connective tissue disorder, focused my attention on other abnormal physical features of mine that I’d previously not dwelled upon: my skinny wrists, long arms, slightly widely spaced eyes. I also sometimes feel at the threshold of the world, to borrow Laing’s phrase: keen to find connection and contact with others, nervous about being misunderstood. Maybe we all feel that way sometimes.

Like so many of my generation, I spend too much time on Facebook and Twitter – and perhaps too much time fixating on likes, retweets, shares. In the same way that The Lonely City, for Laing, is part-mask, part-externalisation of her loneliness, this review is probably – for me – partly a mask that hides a fuller exploration of my own loneliness, and partly an attempt to expel my feelings outwards, an attempt to cope with those feelings and a hope that expressing them might strike a chord with others.

Artists seem historically to have been more willing than academics to explore loneliness. As I was writing this piece, a friend sitting across from me played White Denim’s ‘No Real Reason’, which contains the line, “I’ve got no real reason for my loneliness”. The week before, I watched Charlie Kaufman and Duke Johnson’s Anomalisa, a stop-motion animation film that tells the story of a desperately lonely customer service expert, whose yearning for intimacy leads to distorted expressions of love. At Christmas last year, LCD Soundsystem released a new single, ‘Christmas Will Break Your Heart’, with the lyrics, “If your world is feeling small/There’s no one on the phone/You feel close enough to call/Christmas will crush your soul.” Around the same time, I read Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life, a novel about how deeply distressing childhood trauma can contribute to an adult life of loneliness and detachment, even against a backdrop of wealth, success, and companions.

In contrast, there are numerous academic disciplines that have hardly investigated loneliness. Frieda Fromm-Reichmann (quoted by Olivia Laing) said in the mid-twentieth century that,

Loneliness seems to be such a painful, frightening experience that people do practically everything to avoid it. This avoidance seems to include a strange reluctance on the part of psychiatrists to seek scientific clarification on the subject.

While there have been some advances among psychiatrists and scientists in the field of loneliness since Fromm-Reichman was writing, a similar comment could still be made today about academics working in political theory (an area of interest for me), who appear to have been strangely reluctant to seek conceptual clarification on the subject.

It’s likely there are references to loneliness in political theory sources that have been overlooked or neglected. Political theory texts discussed in academic circles (which reflect an Anglo-American bias and are far from globally representative) certainly address loneliness, though usually indirectly. Thomas Hobbes, in his seventeenth century work Leviathan, famously observed that life in a pre-government state of nature was “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short”. The fact that “solitary” is listed here along with other pejoratives suggests that Hobbes was gesturing at something like loneliness (as opposed to the more positive facets of solitude). He might be taken to endorse the idea that avoiding loneliness – or at least, solitude – is one of the reasons for establishing the State. But Hobbes didn’t expand on this tantalising reference.

Thomas Paine, the thinker and pamphleteer who influenced the French Revolution and constitutional stirrings in America in the late eighteenth century, wrote of the opposite of loneliness: the value of “a system of social affections”, which he said was “essential to happiness”. But he didn’t discuss the effects of a breakdown in this “system of social affections”, or the harms of loneliness. In the nineteenth century, in the Philosophic and Economic Manuscripts of 1844, Karl Marx spoke of the “estrangement” of labour, and the way in which conditions of labour under capitalism create a sense of detachment akin to loneliness. Again, though, Marx didn’t use the term loneliness. Nietzsche mentioned solitude, too, in brief and elliptical terms: “I delude myself as to my solitude,” he wrote in Beyond Good and Evil, “and lie my way back to multiplicity and love.”

It isn’t until Hannah Arendt’s 1951 book The Origins of Totalitarianism that we find an extensive treatment of loneliness from a political-philosophical perspective. Like Laing, Arendt underscored in The Origins of Totalitarianism that loneliness is both painful and an important part of human life. “[L]oneliness is at the same time contrary to the basic requirements of the human condition,” wrote Arendt, “and one of the fundamental experiences of every human life.” Like Laing, she distinguished loneliness from solitude, crediting the ancient Greek philosopher Epictetus (also quoted by Laing) for this distinction, but noted that solitude can slide into loneliness; “this happens”, she observed, “when all by myself I am deserted by my own self”. Arendt went on to link loneliness to totalitarianism (in an argument that might be relevant to investigations of the causes of terrorism today) by claiming that lonely people are less discerning about the collectives that they join: loneliness, then, can foster totalitarian collectives. Arendt presciently worried about the worsening state of loneliness among populations, at least in developed countries: “once a borderline experience usually suffered in marginal social conditions like old age”, she wrote, loneliness is now “an everyday experience of the evergrowing masses of our century.”

“I delude myself as to my solitude,” Nietzsche wrote in Beyond Good and Evil, “and lie my way back to multiplicity and love.”

Guy Debord’s 1967 work, The Society of the Spectacle, which inspired much student action globally in 1968, did not address loneliness directly, but outlined how a society increasingly focused on capitalist consumption creates isolation. In the sweeping language that is characteristic of the book, Debord wrote that “modern consumerism” and “commodity abundance” can end up “falsifying all social life”. Most powerfully and pithily, Debord said: “The reigning economic system is a vicious circle of isolation.”

Since Arendt and Debord’s work, loneliness has hardly been the subject of extensive analysis in political theory. Thomas Dumm’s 2008 book Loneliness as a Way of Life points to the gap in the academic literature on loneliness, but the book is more a personal reflection on Dumm’s loneliness than a lengthy conceptual investigation. Communitarian political theorists such as Charles Taylor and Michael Sandel, working especially from the 1970s until the 1990s, have underlined the need for social connections for a healthy human life. Related disciplines like sociology and political science have been more willing to address loneliness, with Robert Putnam’s 2000 book Bowling Alone providing empirical evidence of increased alone-ness in American culture, exemplified by the decline in group bowling practices. (And foundational works in sociology, such as Durkheim’s work on anomie, have addressed closely related concepts.) Overall, though, political theory and related disciplines have been a little quiet on the emerging social challenge of loneliness.

This is a shame, but it provides an opportunity for scholars and writers working in these fields. Work in political theory could provide sharper definitions for scientists (including psychiatrists) working on loneliness, building on Laing’s book. What kind of negative or unpleasant experience is required for a person to be lonely? Is Laing right to say that loneliness “ranges from discomfort to chronic, unbearable pain” – are all of these feelings on the spectrum of pain feelings of loneliness? And what kind of ‘lack’ is at work when a person feels lonely? Is loneliness related to a lack of social contact, a lack of connection, or a lack of love? How much weight should be placed on subjective experiences of loneliness, as opposed to objective measures (such as the number of acquaintances or companions a person has)? These theoretical questions remain to be answered and could be of urgent practical importance. A focus on loneliness in the present from a political perspective could prompt a more thoroughgoing review of the place of loneliness in the history of ideas. There could well be ideas about loneliness expressed in indigenous cultures’ oral histories and religious texts. A historical scan might enrich our contemporary understanding of loneliness, and provide some sense of whether loneliness is a timeless concern or a contemporary phenomenon.

A final issue raised by The Lonely City concerns the appropriate political response to loneliness. Laing mentions the political dimension of loneliness in passing, though of course her book is more a personal account of experience than a work of policy prescription. What role, if any, does the government have in addressing loneliness?

Laing records that David Wojnarowicz died “due to government neglect” of AIDS, that phrase appearing on a banner at a memorial for Wojnarowicz, with Laing hinting that there has also been government neglect of loneliness. She wonders whether it’s “fear of contact that is the real malaise of our age”. Taking this point further, she notes in the final paragraph of the book that “[l]oneliness is personal, and it is also political”. The solution to loneliness lies not only at the individual level – “learning how to befriend yourself” – but also at the structural level: “many of the things that seem to afflict us as individuals are in fact a result of larger forces of stigma and exclusion, which can and should be resisted.” Elsewhere Laing explains that research on stigma from UCLA shows that it, like loneliness, can have very physical manifestations, such as “a decline in immune function due to ongoing exposure to the stress of being isolated or rejected by the group”. Stigma and loneliness are not purely subjective experiences, then, but can be tied to particular medical consequences – consequences that would appear to make loneliness an appropriate subject of government action, if it’s easier to justify government action where inaction causes clear medical harm.

One upshot of this analysis is that in countries facing an epidemic of loneliness, there should be a greater policy focus on addressing stigma and exclusion at every stage of life, focused on particular at-risk groups and people. The Lonely City reminds us that we need to be vigilant about stigma towards the LGBT community, and towards those who are physically unusual. But racism, sexism, able-ism, and other forms of prejudice remain major causes of concern all around the world. Whether the experience of loneliness is different for members of racial minorities or low-income groups also requires further political reflection – a point somewhat neglected in Laing’s book. It may be, too, as suggested by Guy Debord, that neoliberal economic reforms – with the accompanying emphasis on ideals of competitiveness and ruthless individualism – have made loneliness worse by isolating individuals from each other and undermining ideals of community. If this is right, the issues raised in Laing’s book strengthen the case for unwinding some of these economic reforms (which resulted in deregulation of parts of the economy, privatisation, and tax cuts).

There’s some evidence in New Zealand on these questions, and the evidence suggests that loneliness is a real problem – perhaps one of the problems of our time. Younger people in this country are the loneliest group, according to the Ministry of Social Development’s just-released Social Report: 16.8% of those aged 15–24 were likely to feel lonely some, most, or all of the time in the last four weeks. Women, on average, are lonelier than men. Māori and Asian people are noticeably more lonely, on average (16.6% and 16.7%, respectively) than Pasifika and European-background New Zealanders (13.5% and 13.2%, respectively). Unemployed people were much more likely to feel lonely than employed people, and those with incomes of under $30,000 had double the rate of loneliness of people with incomes over $70,000.

Could we also pursue something like a ‘politics of love’ to tackle loneliness? This is an idea I originally raised in an article co-authored with Philip McKibbin, and most recently in a contribution to Morgan Godfery’s edited collection The Interregnum. A host of recent books have referred to the place of love in politics, including Martha Nussbaum’s Political Emotions: Why Love Matters to Justice and David J. Richards’ Why Love Leads to Justice: Love Across the Boundaries. However, these books haven’t squarely addressed a love-centred politics (one that is hinted at in the work of James Baldwin, Cornell West, and others).

If loneliness is something akin to an unpleasant absence of love, as Laing suggests, then a politics founded on love might be at least a partial antidote to loneliness. A politics of love might address the fact that, in Valerie Solanos’ words, “[o]ur society is not a community.” Interestingly, Hillary Clinton has made halting (perhaps superficial) steps in this direction in recent times, when saying, “we need more love and kindness in this country” in the US presidential primaries. Jeremy Corbyn has also talked of the need for “a kinder politics”. And an Australian MP, Andrew Leigh, talked directly of “the politics of love” in a speech in August 2016.

A politics of love is a politics motivated by love, where politicians aren’t motivated by self-interest or financial gain, where love is the lodestar for policy and political decisions. Love could be interpreted in different ways by different groups, in the same way that freedom is interpreted in different ways by different groups; the important point is that love would be at the centre of decisions. On one interpretation, a politics of love might require more robust support for beneficiaries and a move away from mass incarceration – both policies that could address the loneliness of particular individuals (namely, those receiving welfare benefits and those in prison). A politics of love might not address everyone’s loneliness. There might still be people like Henry Darger, “islanded” in society (in Laing’s terminology), who feel at a distant from communities; as Laing points out, not all “difficult feelings” are “a problem to be fixed”. But it could be a start.

*

When Laing writes about Henry Darger, she writes that the way he made art “out of actual pieces of the world” was to trace them: liberating figures and objects from past contexts and reusing them in different ways, thereby creating new artistic contributions to put out into the world. In The Lonely City, Laing does her own tracing. Faithful to the figures she focuses on, she draws them in outline, allowing herself to nudge them away from their context so that they’re relevant to our time. She’s produced a magisterial work that will allow others to do their own tracing around her sketches, including the tracing of a political response to loneliness. Most of all, Laing has bravely stood in solidarity with all those who find themselves in a state of loneliness in our time, in the outer ring of their community, at the threshold of the world.