Shitting in the Ferns: James K. Baxter and Poetic Honesty

Canadian writer James Ackhurst discovers James K. Baxter, his own poetic voice, and the different types of homecoming and belonging.

Canadian writer James Ackhurst discovers James K. Baxter, his own poetic voice, and the different types of homecoming and belonging.

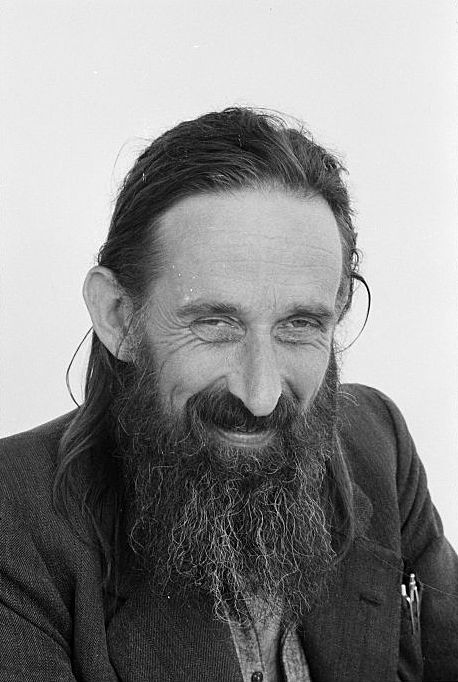

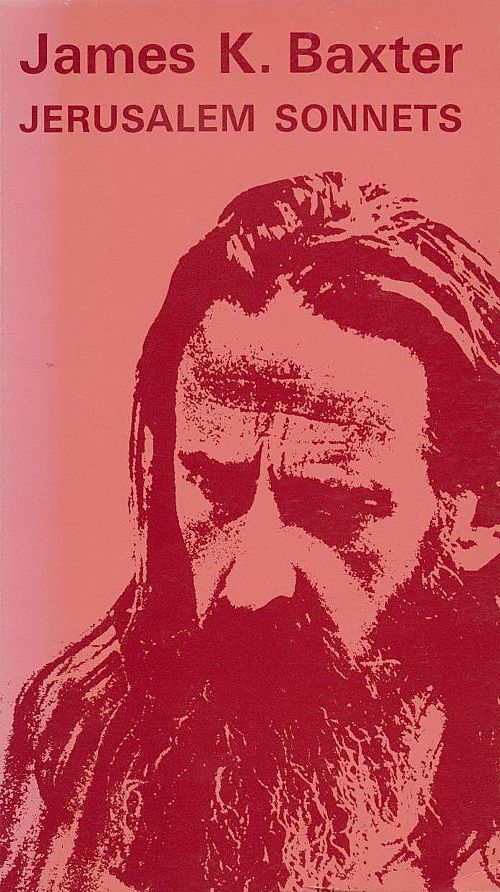

“…And maybe check this out as well, by possibly New Zealand’s greatest poet.” It was the last of three or four books that he was lending me: a slim, pinkish volume. It’s November, a weird time for the weather to be thawing, and only my fifth month in New Zealand. I’m stranded at home, recovering from an operation, and my friend has brought me some books.

I say something polite, but I’m groaning inwardly. As a Canadian, I know pretty much what to expect from “possibly New Zealand’s greatest poet.” The options are limited. It’ll be like Charles G.D. Roberts, securely colonial, turgid, patriotic, and straining for effect. Or A.M. Klein – too clever by half, ostentatiously modern and worldly-wise. Whatever it was like, I was sure it would display the characteristic marks of my native land’s literature: an obsession with landscape, a certain misplaced narcissism, and above all an ever-apparent need to impress, to prove oneself to the world.

At some point after my friend left I picked up the book and noticed something I’d missed before: a sketch – was it a photograph? – on the cover, of a man with a heavy beard and hair like Jesus’. I opened the book just to skim it, and found myself reading a couple of poems. The guy’s talking about lice in his beard, and he’s some kind of religious fanatic; what century are we in? And then this:

A square picture of that old man of Ars

Whom the devil so rightly cursed as a potato-eater

Hangs on the wall not far from the foot of my bed –

Gently he smiles at me when I undo my belt

And begin to hit my back with the two brass rings

On the end of it – twenty strokes are more than enough –

Soon I climb wincing into my sleeping bag

And say to him – ‘Old man, how can I,

Smoking, eating grapefruit, hack down the wall of God?’

‘By love,’ he answers, ‘by love, my dear one,

By love alone’ – and his hippie hairdo flutters

In a wind from beyond the stars, while I stretch out and dream

Of going with Yvette in a shaky aeroplane

Across a wide black gale-thrashed sea.

I thought then, and think now, that this is one of the most extraordinary poems I’ve ever come across. Who is the old man of Ars? Was he Jesus, with his hippie hairdo, his incitement to love, and his enthusiastic – or perhaps merely tolerant – grin at the speaker’s self-flagellation? As for that, what is the poet doing beating himself with a belt? He’s clearly in the age of hippies and air travel, so what on earth is he doing pretending to be some sort of medieval ascetic? Why does he think eating grapefruit will stop him hacking down the wall of God?

Along with my confusion, there was so much in these lines that connected with me. The reminder to treat ourselves kindly, whatever schemes of self-improvement or humility we’ve embarked upon. The hankering for cigarettes and grapefruit; even the oddly archaic, and resolutely un-American, spelling of ‘aeroplane.’ The echo, on the cosmic (or at least meteorological) level, of the thrashing of the body in the unstoppable thrashing of the sea by the winds. And that final image itself, of a shaky aeroplane flying over a wide black sea, that seemed to say so much about the fragility and daring of love.

Soon I am reading a perfectly-turned sonnet about defecating in the woods, and I know that this is all that Canadian poetry should have been but wasn’t. I read the collection – Jerusalem Sonnets: Poems for Colin Durning (1970) – to the end in one sitting; thirty-nine sonnets, as the poet says in the sequence’s closing lines,

From Hiruharama,

From Hemi te tutua.

*

Hemi te tutua, James the Nobody, from Hiruharama, Jerusalem, a tiny village on the banks of the Whanganui. Or that’s what my friend told me. Who was this other James, this Hemi who annouced himself Nobody, like Odysseus did to the Cyclops?

It was hard to say. I kept off Google for a reason – call me old-fashioned, but I’ve always thought that a poet’s self-fashioning is an aspect of their performance, and getting to know the self (or the persona) that emerges from their poetry is one of the most intimate aspects of interpretation.

Soon I am reading a perfectly-turned sonnet about defecating in the woods

So who was the Hemi that emerged from this new Jerusalem? For a start, he was a contemporary, or not quite – he was someone from the 60s or 70s. He had the look – the long hair and beard, the leather jacket. He smoked, meditated, slept around. He spoke with the eager, self-conscious coolness of that generation: ‘stoned on grog,’ ‘stoned on pot,’ without shunning expletives. At the same time, there was a certain formality to the language, a poetic heightening achieved in part by the seemingly arbitrary admixture of words that were recherché, esoteric, even liturgical. Here he is describing the lice that infest his beard:

But they have no Pope or King, Colin;

Anarchist, acephalous; they’ve got me stuffed!

It’s often exclamations that define a voice: my father’s bizarre Maritimer’s appeals to mackerels, Catullus’ ‘o,’ Hopkins’ ‘ah!’ (‘and with ah! bright wings!’). For James the Nobody, it was ‘man,’ an effusion caught somewhere between the hip and the Biblical.

Man, my outdoor lavatory

Has taken me three days to build…

That, actually, was one of the weirdest things about this new voice – the unexpected marriage of the high and low, the loftily sacred and the unapologetically profane. The profane was there in the crude references to contraception (‘no rubber plugs or pills’), in the old tin of tobbacco, in the arse-wiping and naked defecation. But the sacred was there, too – in a spirituality that was at the same time deeply devoted and all over the map.

What kind of a believer was this guy? The man of Ars wasn’t Jesus, but he was some kind of Christian mystic (I let Wikipedia tell me that much). The poet was concerned to hide his ‘defecation from the eyes of the nuns’ – who were always lingering in the background, somehow. And Christ was everywhere: ‘the cross of Te Ariki,’ the Master of the World that was the weight on the back of the poet’s donkey. But there was Buddha too, and Buddhist mystics I’d come across in meditation groups – ‘old Milarepa,’ who gave ‘His bones to the bonfire.’ And there was more, too – ‘the brown river, te taniwha’ – Māori words that recognized and named the holy power of nature.

Wasn’t there something simplistic, even patronizing, about seeing Māori as unspoilt, unsophisticated nature-mystics?

All of which, it struck me, came close to my recipe for a bad poet, and for a bad poet of the least interesting sort, a bad Canadian poet. Wasn’t there something simplistic, even patronizing, about seeing Māori as unspoilt, unsophisticated nature-mystics? Wasn’t there something all too 60s about the easy, ahistorical religious syncretism? And something complacent in the self-fashioning as a saint, in the use of religious language to heighten the everyday lusts (for tobacco, for grapefruit)?

Yes, yes, and yes. But I still liked the poetry, even if I wasn’t sure I would have liked the poet. It had what I’ve always thought of as the essential quality of true poetry – intimacy, by which I mean an honesty about one’s own experiences, coupled with a sincere and skilful effort to communicate them. The honesty of James the Nobody was partly responsible, I found, for the strange hybridity of his poetic voice: there was no effort to make the collection coherent or its diction consistent, and because of that Elijah was left to jostle with weta, the yogi Milarepa with cars with advertising slogans written on them. Best of all, the poet’s experiences were allowed to be what they were, impossible or not:

It is not possible to sleep

As I did once in Grafton…

It is not possible to sleep

The sleep of children, sweeter than marihuana,

Or to be loved so dearly as we have been loved,

With our weapons thrown down, for a breathing space.

Where was Grafton? It wasn’t Paris or London, and it never occurred to the poet to pretend it was, or to insist that Grafton too could be Somewhere. It was Nowhere, in a poem by a Nobody, a undistinguished suburb where the impossible happened.

*

Frankly, the fact that Grafton was a Nowhere inhabited by a Nobody was an enormous relief. The great task of Canadian poetry, for far too long, was to make Nowhere into Somewhere. Evan Jones and Todd Swift, in their dispiriting Modern Canadian Poets, write that ‘there is a long-standing Canadian cultural myth that to be a Canadian poet is to be part of the country’s geography, whereas elsewhere to be a poet is to be part of poetry’s history.’ But the real problem isn’t that Canadian poets have written too much about Canadian geography, but that their Canadian geography hasn’t really reflected what it’s actually like to live in Canada. What professed to be a deep connection to the wilderness was rarely more than a kind of rhetoric.

One of the great reliefs of Baxter is that his rivers are actual rivers

Or a variety of different styles of rhetoric, all loudly announcing the same thing, that Canada has arrived, that our mountains are just as worthy and as lofty as your mountains, that our cities now have reasonable numbers of people in them. You can go for the mystical nationalism of Alfred Bailey, who tips both history and metaphysics into ‘Border River’ in a vain attempt to give it some colour and direction:

Look at this river in the book of rivers…

For both countries, bleeding from the same heart,

singing a song of waters tossed by history,

found their own flag, strung from the beating halyard,

unfurled in a neighbour’s eye by the hand of faith,

bound by the wonder of wind, with love for signal.

Or perhaps you may prefer the urbane sophistication of A.M. Klein’s ‘Montreal,’ which effortfully demonstrates how two great languages can merge into none:

O city metropole, isle riverain!

Your ancient pavages and sainted routs

Traverse my spirit’s conjured avenues!

Spendor erablic of your promenades

Foliates there…

Whichever ‘rout’ you chose, it’s clear you’re not going to get to Canada. You’ll get to some weird cultural no-man’s land caught halfway between France and England, between Keats and Rimbaud, between Georgian hyperbole and modernist claptrap. If you want to know what it was actually like to live in Canada in those days, you’re on your own. As you are if you want to know what these poets felt about it.

One of the great reliefs of Baxter is that his rivers are actual rivers. What’s more, they’re actual rivers in New Zealand, without being New Zealand Rivers:

At evening the sandflies would rise from the river

And bite our ankles while we waited

For a tug on the line.

It wasn’t always so. It’s only recently that I’ve managed to get my hands on a reasonably-priced copy of Baxter’s Selected Poems (his poems are curiously hard to get a hold of, even in New Zealand). And I must say I was disappointed, but not surprised. Baxter’s early poetry is exactly as I expected it to be: over-wrought, over-eager, over-cooked. It has the usual colonial mixture of landscapes, wearily predictable politics, and ballads about the small-town everyman who was apparently the periphery’s main gift to the Empire. The name-dropping of local plants is relentless.

As I read the Selected Poems (1982), I kept on flipping forward to Jerusalem Sonnets, and to the other two late collections I’d subsequently found second-hand copies of: Jerusalem Daybook (1971) and Autumn Testament (1972). I’d read and re-read them maybe half a dozen times, but I still found myself wanting to go back to them. Luckily or unluckily, they’d been a constant companion to me during my first couple of years in New Zealand. And, luckily and unluckily, they’d been one of the major inspirations for my own verse.

*

Like Baxter, I started writing poems when I was about eleven or twelve. For a long time, and inevitably, my poems displayed the usual virtues and vices of young poets. They were dense, allusive, packed with tricks and devices I’d learned in English class. There were a few flashes of freshness (of the sort that comes less easily now), but also a suffocating amount of ostentatiousness, of look-at-me lyricism that made the poems stray far from home.

At college, I wrote less, submerged as I was in academic work. A year doing a Master’s in London somehow allowed me more time, and once or twice I wrote things I was happy with. They had lyricism, and form, and – increasingly – restraint. I used to walk home along the Wandsworth Road, arranging and re-arranging the phrases in my head:

So were we chasing something from the start?

We seemed to lust after some cure or output.

Unravelling along the liquorice route,

Or merry-going-round town’s lemon circuit,

A ferris-wheel reiterating lime.

Then riding red to London’s apple heart,

Or coursing down the blue wire like a vein.

But my poetry needed to chill out, and so did I. In California I had a stab at a beat phase, though it took me a while to write my first completely unrhymed poem (in blank verse). That was in

San Francisco, where I’d run downhill

to meet you every night, the city lights

swinging to meet me like a chandelier

or like I was an astronaut or diver

plummeting down into the Zodiac

or some sunk galaxy of coral.

At least it had zany similes, and swearwords.

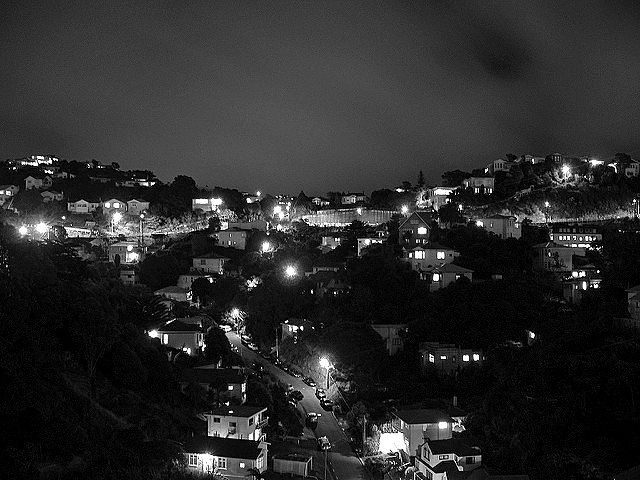

When I moved to New Zealand, I suddenly had time to write poetry. Lots of it. I didn’t know many people, and didn’t have much to do in evenings or on weekends. And I also had a long walk home every night through the Botanic Garden – the best walk home from work on earth.

The best walk home from work on earth?

You bet – although you have to walk it

forty times to walk it once.

And words won’t do; but here we go.

The words came, because I had time for them. They came from my experience, from the things I was seeing in this new land, Aotearoa. And one of the things I’d been experiencing was Baxter:

Another day, still other longings;

another walk down through the garden…

What was the longing for? Home, friendship, other things. It was weeks after we’d first met and become friends that I ran into her in the same café. It was Easter Sunday, in fact, and I’d just been to church, where there’d been a sermon on Christ’s weirdly rancorous first words after his resurrection: noli me tangere, “Don’t touch me.” And later on I wrote a poem:

My mother sends a card for Easter:

these three abide: Faith, Hope, and Love.

She hopes I'll get to church today;

I do, and stand there at the back

to hear the priest tell us straight up

that Jesus Christ rose from the dead -

something I never could believe,

my only quibble with the faith…

so I skulk out to get some breakfast,

and find that café that I met you in;

I read the papers, order a fry-up.

I'm working on the garlic mushrooms

when who should walk in through the door

but you again, still hot as hell

and trailing your obnoxious boyfriend?

I walk out by the bay and look

for faith and hope. Well, there's still love.

But that's the whole damn problem, Mom!...

But when I make it to the point

who should I see but Te Ariki

hoeing through the clods of sea,

whose love, I know again, is best

as his bright gaze declares: Don't touch me.

It will seem presumptuous to New Zealanders, but everything I learned about Baxter made me increasingly sure he’d been sent to me as some sort of guide. Once at work I signed my name ‘James K.’ and a colleague in the English department wrote back to tell me I didn’t want to be confused with the other James K. around here. Or did I? My affection for him grew every time I read another ode to the lice in his beard.

A poet needs to work through a lot of influences before they can work free of them

That poem I’d written was part of a sequence I was calling Wellington Sonnets. It had all the late Baxterisms I’d come to love – the blend of biblical language and te reo, the green shade of its Christianity, the brave and slightly pathetic admission of the poet’s own most basic needs. Even the self-pitying apostrophe of my mother was an echo of late Baxter’s signature exclamation, man.

It seems obvious to me now that the voice in that poem is more Baxter’s than mine. But if his career is anything to go by, I can take comfort in the idea that a poet needs to work through a lot of influences before they can work free of them. And when I read the other poems in that sequence, I realize how far finding Baxter’s voice has taken me towards finding my own.

*

It was a couple of years after I wrote that poem that I found out who Mother Mary Joseph Aubert was. Up to that point she’d jut been another name in a Baxter poem. And now I was hearing that she’d been a mystic in Hiruhirama long before Baxter – and had even grown cannabis there for medicinal purposes, a move the poet would surely have approved of. We were sitting in an Indian restaurant in Newtown crying into our curries, because we’d committed the sin of ordering them ‘hot.’

She always knew things about mystics. And about planting seeds. She needed knowledge like that for her communal house up on the slopes of Aro Valley, where she and her housemates grew herbs and kumara, and kept chickens and bees.

How long had we been together at that point? How long did we have left? And was that the night that we rode her rusty old bike home together along the Holloway Road? It can’t have been the same day that we paused beside the little community garden on Aro Street to lift up the huge, leonine head of that sunflower – why was it so droopy? Later I brought Jerusalem Sonnets up to her hippy house in the hills so I could read her the sunflower poem.

Maybe a month ago, I wrote to her on Facebook, telling her to keep the book. But she never liked receiving gifts. A few weeks later my flatmate discovered that familiar, slim, pink volume in our mailbox, the place of the sunflower sonnet marked by an envelope full of seeds:

Yesterday I planted garlic,

Today, sunflowers – ‘the non-essentials first’…

And they will turn their wild pure golden discs

Outside my bedroom, following Te Ra

Who carries fire for us in His terrible wings

(Heresy, man!) – and if He wanted only

For me to live and die in this old cottage,

It would be enough, for the angels who keep

The very stars in place resemble most

These green brides of the sun, hopelessly in love with

Their Master and Maker, drunkards of the sky.

I’ve been living in this shared house for a year or so, and it’s more than enough. My housemates and I decide to plant the sunflowers as soon as it’s spring. Whenever I read the poem, or any of the poems in Baxter’s Jerusalem period, I’m reminded again of all the different types of love, of homecoming, of belonging.

Whenever I read...any of the poems in Baxter’s Jerusalem period, I’m reminded again of all the different types of love, of homecoming, of belonging

I left Canada when I was twelve. It didn’t really feel like a homeland then, and every subsequent place I’ve moved to has felt like less of one. But some things help us move in. Poetry that actually sees the lives we’re living. Flowers that tell us how to follow the sun.

I’m going to be leaving New Zealand for a few months now, though I’ll be coming back. I don’t know where she’ll be on that journey, or where Hemi te tutua will be. But when I arrange the lines of my poems now there are two dream-journeys that come up.

One is a canoe pilgrimage up the Whanganui, along a real, impure river, past Atene and Jerusalem and back to ordinary life. And another is a trip home on a creaky old bicycle, along a dark, wind-haunted street.

Feature Image: James K Baxter Ref: EP/1971/1098-F, Alexander Turnbull Library.