Beauty Is A Rare Thing

Philip McSweeney on Ornette Coleman

As anyone even passingly familiar with jazz knows, the 1950’s were defined by the Cool: a divarication from bebop’s fire and brimstone, defined by subtleties and an arch melodic ‘coolness’. Cool jazz was created, mid-wifed and nurtured by the pre-eminent Miles Davis, so it’s logical that the genre culminated in Kind of Blue, whose stature among music fans would render any attempt at description redundant. Suffice to say even those who have scant - or no - interest in jazz are likely to have a copy of this in their record collection, or CD troves, or, like, on a 1TB hard-drive lying around somewhere.

Rather than talking again about the album’s music, let’s appraise the pictures. The cover’s famous, striking, and effortlessly hip. Davis’ visage is captured blowing soulfully into his trumpet, somehow at once bedroom-eyed and detached. Then there’s the inset photo, with Davis’ hand on (white) pianist Bill Evans’ shoulder. It functions as a palpable display of cameraderie, sure, but it also reveals the power dynamic of the recording. Davis is clearly in charge, and he’s directing the pianist, no matter how congenially. The photograph has become iconic, and rightfully so; the cover is iconic, and rightfully so; the music is iconic, and rightfully so. Everything about Kind of Blue screams capital-s Statement.

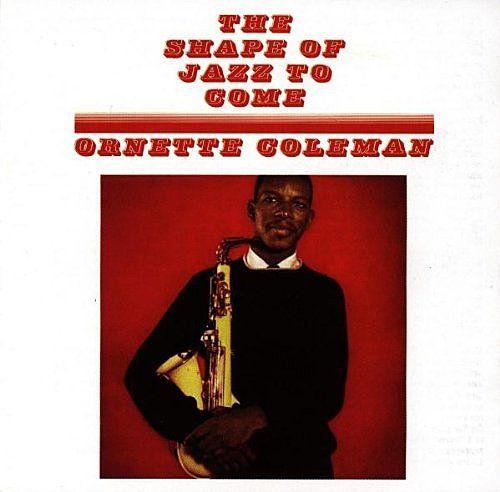

By way of counterpoint I proffer the cover of The Shape of Jazz to Come, released in the same year as Kind of Blue, David Brubeck’s Time Out, and Charlie Mingus’s Mingus Ah Um...

...and it must be a joke right? A daguerreotype of Ornette Coleman in a Grandpa’s sweater that I’m willing to better has never been fashionable in any sartorial cycle, alto saxophone slung uncomfortably about his torso, looking not unlike someone uncomfortable around infants whose just had one thrust onto him by a doting mother (‘no go on, hold him! Come on!’). His mouth looks more ready to dispense a Dad joke than play the instrument he’s holding.

His eyes, though, stare unflinchingly at the camera in a way that makes them disquieting to look at for more than a couple of seconds, like staring at the sun, and look, there, just above the pictorial element, the title of the album screaming at you in a blisteringly red font, a bold statement of intent at odds with the rest of the album cover.

As a title, The Shape of Jazz to Come is a bold claim, and it’s often misinterpreted as Coleman’s hubris - as if he could have have known how prescient, how prophetic, that title would turn out to be. But it wasn’t his idea, let alone his claim. Coleman favoured ‘Focus on Sanity’, which would have made that track the titular one, but his producer, Nesuhi Ertegun, felt that ‘The Shape of Jazz to Come will give our listeners a hint, an idea about the uniqueness of the LP’.

Why Coleman assented to this change is a mystery, but I suspect it lies in his sardonic sense of humour. Surely he must have loved the irony in using the word ‘shape’ as a referent to a describe an album that completely rejected improvisation based around chordal structures, or indeed structure at all (one of the thrills of listening to the album is that solos come without warning or clue; even after repeated listens you still don’t know exactly when Don Cherry’s gonna blast the shit out of his cornet). I wouldn’t be surprised if the uncool, antithetical-to-Kind-of-Blue cover was a big-hearted dig at cool jazz’s wane too, knowing Coleman’s aversion to the genre and his predeliction for shits and giggles. I’ve always thought this illustrative: according to possibly apocryphal anecdotes, one producer walked in on the recording session and, unamused, told him to rein his playing in: Coleman responded by playing his saxophone so it emulated a horse whinnying. Needless to say, the goof-off made it to the final cut.

*

Just a caveat as I go on, and keep digressing into mentioning other artists and other records in ways that might seem like tangents, In any discourse about jazz, and about Ornette Coleman especially, other frames of reference inevitably rear their heads. The effect can be overwhelming, but it's also crucial, I’ll argue, for three reasons:

1. Just to try and contextualize a performer's work, and to help orient readers around sky-scraping achievements in the genre. Reviews of Kid A when it came out couldn’t have - and shouldn’t have - avoided the words ‘o.k.’ and ‘computer’; no retrospective on Modernism will ever not mention Mrs. Dalloway, etc.

2. Jazz, arguably more than any other genre, operates on a kind of post-structural level where every example of it references or exists in relation to something else, which in turn relates to something else that is key to rendering the former comprehensible, a coding familiar to you if you subscribe to the idea that employing words does not refer to anything concrete but instead a continuum of other words. What i’m arguing for here, i guess, is jazz as logocentricity; or better yet, jazz as a language that needs referents to complete analysis in the same way language needs suppositions to complete sentences and thus meaning. This is especially true when it comes to someone as integral in formating the DNA of jazz as Coleman was (but more on that later). Put it this way: there’s a reason why Derrida and Coleman got on like houses on fire, and why the New Yorker eventually saw fit to publish a dialogue between the two in 1997.

3. This is kind of a synthesis between 1) and 2) but to get an idea of how individualistic, eclectic and dizzyingly brilliant Coleman was, to really his genius, it’s necessary to delve into (the often bifurcating) advances made in jazz during his lifetime.

*

While The Shape of Jazz to Come is often touted as the ‘first avant-garde jazz album’ and/or ‘the genesis of free jazz’, I don’t think either of those things are true. I would assert that in terms of avant-jazz, The Shape was beaten to the punch by Cecil Taylor’s Jazz Advance, released two years prior, and my knowledge of the genre is good but hardly encyclopedic. Jazz scholars with more time, research and inclination than me have traced the origins of avant-garde jazz back to a specific cut of ‘Rhapsody in Blue’ recorded in 1924. This doesn’t diminish what The Shape of Jazz to Come did when it disassembled and re-coded the DNA of jazz and opened it up to a world of non-idiomatic communion, of transcendental squall and beautiful, richly-hewn parps and wheezes. Nor does it mean that it didn’t do it on Coleman’s own terms, which basically meant no terms, no rules or rigidities or blueprints. In that sense, claims of a ‘genesis’ are correct.

But the genesis of free jazz? Certainly much of the soloing is atonal, non-chordal, non-modal, non-idiomatic, but The Shape... didn’t dispense with harmonic structures. Shit, Lou Reed (say what you will, the man knew his way around a catchy tune) called the shimmeringly mournful melody of ‘Lonely Woman’ ‘the most perfect melody put to tape bar none’. I mean, there are elements of free jazz here, but it’s more like free jazz as seen through a refracted mirror, or on the opposite side of a free jazz mobius strip. There are rough edges, but the music is never abjectly confrontational or difficult; it’s always anchored in something lovely and conventionally splendid, without losing any sinisterness or vivacity. It wasn’t the beginning of something; it was the end of many of jazz’s preoccupations, forms, motifs. It was the death knell of the conventional.

*

Ornette Coleman’s career, was, as mentioned, wildly eclectic and differing, and in focussing so myopically on The Shape of Jazz to Come I am emulating the mistakes of other obituaries who have focussed on this and his album Free Jazz while ignoring the breadth of his career. I’ll depart from such discussion presently - but first it’s worth looking a little longer at his background.

Ornette Coleman was born and raised in Fort Worth, Texas, and I have no doubt his upbringing in the South allowed him exposure to another kind of predominantly black musical form: the blues. The blues has always infiltrated his playing, no matter how idiosyncratic or abstruse; if there’s one motif that his playing featured throughout a career that spanned seven decades, it’s the tacit allusions to King, to Johnson, and to Leadbelly that always seeped out in his phrasing and his rich, warm sound.

Before The Shape, he had already released two albums under his name. Both of them are fairly generic albeit accomplished hard bop (at the time, cool jazz’s antithesis), remarkable mainly in that they offer no hint of the direction Coleman was to take, although their cool noirish influences and Colemans quintessentially piquant playing style elevate both above the pack.

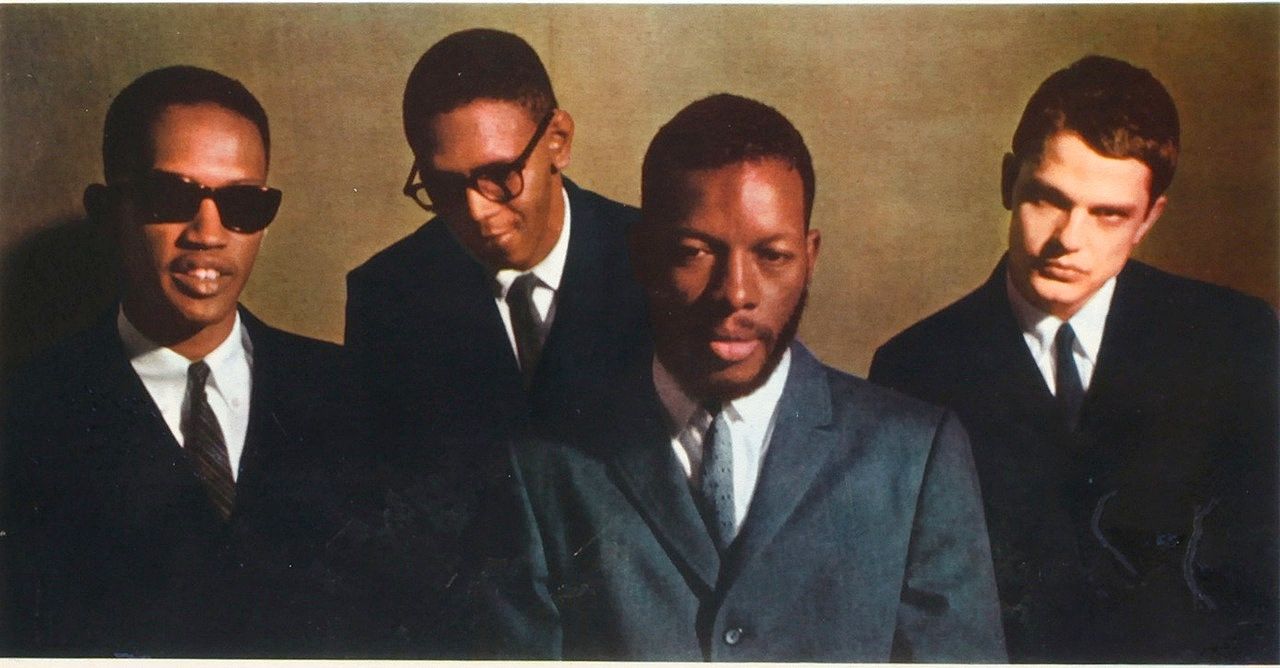

Then came a relocation to New York and with that the epochal residencies at the Five Spot, a world-famous jazz club that began offering residencies to established jazz musicians in 1957. Coleman’s ten-week residency in 1959 begat The Shape of Jazz to Come; he was invited back for a three-month stay the following year. He stuck with previous collaborators Cherry, Haden and Higgins, and added the then little-known musicians Eric Dolphy and Freddie Hubbard to the mix after they demonstrated receptiveness to his vision.

At the end of the 1960, a couple of days before Christmas, the ensemble recorded one of their jams. After consigning an awkward first take to the archives, Coleman decided to release the fruits of their labours. The album was titled Free Jazz. The rest is history; the rest made history.

Released in 1961, about a year after it was recorded, Free Jazz was immediately divisive. Completely unhinged from any semblance of structure, melody, harmony, or anything for the unsuspecting listener to latch onto, the album surged like a torrential flood of caterwauling horns and typhoonish percussion, with the only reprieve being offered in the last five minutes as the album ‘wound down’ - which is to say, collapsed in on itself.

While The Shape was generally, if tentatively, well-received, free jazz led Miles Davis to publicly question Coleman’s sanity (‘that man… is all screwed up inside’) while contemporary reviews eviscerated the album, the consensus being that the music was not only godawful but as insult to injury had actively squandered the talent of the ensemble.. Not for the first time in his life, Coleman was punched in the face by an irate jazz musician, this time Max Roach, when the two happened to pass each other on the street. A couple of days later Roach staged a protest outside the Five Spot, screaming ‘I know you’re in there you motherfucker, you no-good filthy [n-word]... come down here so I can kick your fucking ass’.

Fortunately, time in the jazz-world moves swiftly. By 1962 - free jazz was de rigeur, en vogue. Coltrane had kept Dolphy and snaffled up avant-gardeist Alice McLeod, who was destined to become his wife, and the three were putting on cacophonous, calamitous gigs that sold out. Here’s where things get interesting, for me at least, in the Coleman story. Did he reap the benefits of this new-found fascination with free and avant-garde jazz? Did he stay on the train, continue to explore the possibilities of the genre a paternity test would prove him the father of?

Did he shit. Instead, his next two records were avant-jazz inflected post-bop, recorded at a time when post-bop was at its least popular. And Coleman knew it, but he was bored of free jazz already, wanting to focus on what he referred to in a letter as ‘harmolodics’: ‘the use of the physical and the mental of one's own logic made into an expression of sound to bring about the musical sensation of unison executed by a single person or with a group’. While still based in free jazz, Coleman wanted to achieve a kind of psychological unison at odds with Western notion of annotated tonality.

Indeed, Coleman was always either too early, too late, or too fuckin’ weird. After he signed to Blue Note - even then regarded as the pivotal label of the jazz genre -- he earned ire for employing his son, Denardo, to play the drums on his 1967 album The Empty Foxhole. The issue here, however, wasn’t one of simple nepotism. Rather, his son was only 10 the day he laid down the track. People did, and still do, read this factoid and assume they have enough information to ignore the album, and you’d certainly have to draw a very long bow to call the album the masterpiece, but it is surprisingly...something. Coleman Jr’s nonplussingly acute sense of rhythm was evident even in its nascent stages. The major problem with the album is actually begat of the father.

If we take the liner notes, where Coleman Snr. gushes that Denardo immediately took to the drums after getting a kit for Xmas aged 6, we can at least calculate that Denardo has at least four solid years of practice on his chosen instrument. Ornette, who decided to wean himself off his reliable alto sax, had been playing his implemented instruments - the trumpet and the violin - for less than two. It makes it an interesting album to listen to - for good or ill, it’s unlikely you’ll hear a purportedly ‘strait-laced’ jazz album this bizarre inside the archives of Blue Note or otherwise.

As regards his being too late, I proffer Exhibit A, distinguished jurors: Science Fiction and Skies of America in 1971 and 1972, or ‘Coleman gives this new-fangled ‘Third stream’ thing a try’ - except by this stage Coleman wasn’t even fashionably late to the game. Third stream, for the uninitiated, refers to a genre that synthesises elements of Jazz and elements of Western Classical Music. While this genre quietly manifested itself in the 1950’s, Charles Mingus’s The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady, released in 1963, is generally considered to be the apex of the genre.

For a couple of years after The Black Saint, Third stream was wildly fashionable. But by 1972 electro-Miles and jazz fusion had been and gone as well, and Third stream had been consigned to the stacks of history as a successful but mined-out venture, about as progressive when put to tape as bebop. Except that year, Coleman shredded the memo and hit up the London Symphony Orchestra for Skies.

In Coleman’s entire oeuvre, none of his albums generated as much confusion as those in this era. His free jazz experiments, at least, were polarizing. His attempts at dabbling with Third stream, his weird orchestral compositions that seem to subsist on personal foibles and eccentricities, are just perplexing. Skies of America has been touted as ‘dangerous and rewarding music’ in an allmusic review that originally gave it just three stars; my outdated copy of the Penguin Guide to Jazz calls it ‘a mess’. Even today, no-one knows quite what to make of them, other than they’re best enjoyed at a distance, like some sort of ropable big cat. These are not albums that make obituaries.

Yet among the more braver jazz fans I know, it’s these two albums - especially Skies of America, with it’s occasional, incongruous nods to Native American music - that rank as Coleman’s best, and if you’ll forgive the hubris of myself and a bunch of music nerds, I genuinely think that history will come around, though ultimately it doesn’t matter whether they’re revered or reviled. But that Coleman released an album nigh-on fifty years ago that still doesn’t feel properly processed or dissected or understood in any way, is surely testament to a singular kind of creative and musical flair.

A few years later came Exhibit B: Body Meta, an album that was ostensibly recorded in 1976 and released in 1978, but sounds like it emerged mewling (literally) into the world around 1970, when mixing jazz with rock and funk was de rigeur; by the close of the decade, the likes of Weather Report had pulverized the sub-genre into the ground, and it was as unfashionable as it had ever been. On this album Coleman got funk guitarist Bern Nix and avant-rock guitarist Charlie Ellerbie to battle it out while he played saxophone a la The Shape of Jazz to Come, though it has to be said his playing is a little less recondite and more rock-oriented. Never in a jazz recording have drums, too, sounded so much like a disco drum-machine; the funk is relentless to the point of being kinda tacky.

Needless to say, I love it. I have a massive soft spot for this record, let that be disclosed, but even if i was among its detractors I think it would be hard not to admire it, in the same way you kind of have to admire Outsider Art regardless of whether or not you like or ‘get’ it; this is musical territory being explored by someone who does not give a solitary shit about what’s fashionable. It’s being made by someone who wants to test the limits of the genre, and make something that is above all interesting, music that they know will be relegated to the peripheries but that they enjoyed making, and want others to enjoy too.

Except this isn’t some sort of unknown artifact created outside the boundaries of the jazz scene and later discovered; this is outsider music through a insider’s lens. Coleman was acutely aware of the social codes and mores of mainstreamed jazz culture. His searing individuality and vision comes through because he didn’t abide by them, but it’s not as if he totally eschewed them either. He just, kind of, did his own thing, independently. He didn’t try to be a visionary or excessively worship the past or present - he just, well, did.

After the seventies, Colemans recorded output diminished drastically, although he continued to play live. He tried his hand at film scores and classical work, and collaborated with Pat Methany, with some success, but live was the only outlet for his rangier proclivities. At least until 2009, when Coleman, the wrong side of 80, formed a Jazz trio with luminaries Jordan McLean and and Amir Ziv. The project’s name? New Vocabulary. They recorded their eponymous debut album last year, Coleman now a ripe 84. The album is - you guessed it - searingly avant-garde, this time combining Coleman’s archetypical jazz ramblings with electronica and ambient music.

New Vocabulary was Coleman’s last recorded offering. He passed away on June 11th, in Manhattan, a walkable distance from where the Five Spot used to be; from where Skies of America was premiered at Philharmonic Hall on Independence Day 1972; from a jam spot where he would go with his son, the two of them laughing and jamming and playing for rambunctious ‘hours that felt like minutes’. Denardo was with him until the end.

*

Here we encounter the same problem that all obituaries of sky-scraping figures must wrestle with; how do you distill - or reduce - such a vast, eclectic, often unmoored history into a couple of platitudes? In lieu of even attempting that, a couple of concise and salient take-aways:

- Ornette influenced a wide spectre of musicians, but specifically I’d love for someone with more psychologically nous and acuity than I to explore why his output seems to resonate with post-hardcore musicians especially. Refused named their watershed The Shape of Punk to Come in homage to Coleman’s masterwork; the (under-appreciated) Off Minor and Skies of America take their name from Coleman compositions; in Indian Summer’s seminal emo statement, Science 1994, an unmistakable snippet of ‘Lonely Woman’ can be heard in the background of ‘Reflections on Milkweed’.

If I had to posit a guess, however, I would assert that if post-hardcore is a genre that focuses on freedom from archetypes and structures, and forefronting decidedly individual and personal malaises, then in Coleman’s obstinate individualism and refusal to abide by conventions, harmonies and notations of the ‘mainstream’ fitted these kids perfectly. There can be no greater stalwart or hero, really.

Unfortunately, some of Coleman’s most incendiary albums have suffered from the ‘Seinfeld is Unfunny’ effect, i.e., the blueprint that Coleman painstakingly drew has been mined so thoroughly and so far beyond his original conception that to someone attracted to the avant-garde for avant’s sake, The Shape and Free Jazz are gonna look pretty staid next to, like, the caterwauling assault that is Peter Brötzmann’s "Machine Gun" (won’t someone put that poor pig out of it’s misery?) or Coltrane’s Ascension.

However, Coleman’s work still functions on two levels; it’s brilliant of its own accord, but in terms of forging what free jazz, or shit, jazz period, would become, Coleman’s mad-scientist DNA splicing was integral in a very literal meaning of the word. As historian Richard Cook adduces, Free Jazz ‘set a course for large-scaled comprovisation over the next decade, and is single-handedly responsible for Coltrane’s grandly metaphysical Ascension’.

What I want to make clear is that nothing in Coleman’s entire, extensive oeuvre is the kind you put on during lazy Sunday afternoons, or listen to while sipping on scotch and wearing a fedora ruminatively the way more mild-mannered players eventually succumb to. This is confrontational music, difficult music, sometimes painful and pained music; it is also deeply, deeply resonant, and to achieve these seemingly antithetical qualities is something only a marvelous gift could offer.

Indeed, Coleman’s output exists independently of jazz structures; it communes with them, but only via indirect tangent and retrospective alignment. His music can never be ascribed to cause and effect, and in a genre as dependent on synchronicity and logocentrism as jazz the importance of this in his mythos cannot be overstated. He operated on a different schemata to other jazz musicians, always, even, especially, during times when it would be easier to stay the trodden course (and if that doesn’t define an innovator i don’t know what does). Coleman offers a method of subverting and creating logos and signs: he offers us a way out of the labyrinth.

I’ll be blunt: I love Ornette Coleman’s music but it doesn’t move me in the way Miles does, in the way McCoy does, in the way Coltrane does, and I don’t think it ever will. But his tacit contribution to their explorations, his prodigal individualism, his vision, vim and vigour, his steadfast refusal to be pigeon-holed, or safe, or easy; I find his story, his narrative, more compelling than other jazz musicians, and I find the lessons his journey imparts salutary, inspiring, vital.*

While it’s tempting to imagine the afterlife to which Coleman believed he would ascend as some hoary cliche genius mecca (think: Coleman finally ready to join Mingus, Davis, Coltrane and Roach to have a good long jam), I think in this hypothetical paradise Coleman would be much more understated; he’d check in under his name, kiss his ex-wife on the cheek, offer ‘hey’s to old, departed buddies and collaborators. Then he’d find a dusty, secluded space in an attic somewhere and keep exploring, answering only to his own whims. For some this might seem lonely or dissatisfying; for Coleman it was that, but it was home as well. And, during his tumultuous soloing, he might realize that his death wasn’t the first time his heart stopped: the first was during that moment in Free Jazz, when all the instruments fall away shambolically and then briefly return elegantly, beautifully, one-by-one; a ray of light shot through an overcast cloud.