Bethell, Baker

Sarah Jane Barnett looks at the work of two New Zealand poets separated by a hundred years, and looks at how their experiences, losses, and strengths resonate across time.

Sarah Jane Barnett looks at the work of two New Zealand poets separated by a hundred years, and looks at how their experiences, losses, and strengths resonate across time.

The forest solitudes; think you not truly, then,

The linked light and darkness, laugher and grief

Forecast the consciousness of microcosm, man,

The tuned antinomies of his mysterious life?

– Ursula Bethell, from ‘Forest Sleep’, 1936

‘Come on Poetry,’ I sigh, my breath

whitening the dark. ‘The moon is sick of you.’

We walk the white path made of seashells

back to the orange light of the house.

‘Wait,’ I say at the sliding door. ‘Wait.’

– Hinemoana Baker, from ‘manifesto’, 2014

I read Bethell and Baker’s poems over three days. On the first day I read at my dining table, an oak extendable bleached by water from my son’s plastic bath. I read from Bethell’s collection Time and Place, published in 1936, two years after the death of her lover Effie Pollen. Bethell and Pollen lived together at Rise Cottage, a house Bethell built on the Cashmere hills above Christchurch.

On the second day my reading was interrupted. I’d read Bethell’s memorial poems for Effie who’d died suddenly after going to bed with a headache. For the next six years a grief-stricken Bethell wrote a memorial poem on the anniversary of Effie’s death. A sudden rainstorm made me get in the washing and then I had to pick up my son. Later there was dinner, and then stories in the half-light of his bedroom. That evening I watched a documentary on sake. On the third day I drove to Greytown to stay in a house I’d rented for the weekend. This is all to say, poetry has to fit into the spaces between things.

In the Greytown house I read waha | mouth, Baker’s third collection of poetry. I chose Baker to read alongside Bethell because both are New Zealand women who, to date, have published three collections of poetry. Both write about grief and impermanence. Both lived with a woman for ten years before the relationship ended. Neither had children, although not necessarily by choice. Bethell has often been referred to as someone who nurtured other artists, and Baker, who has taught creative writing for years, continues to influence New Zealand poetry. Both women are representations of their time – the best and most courageous.

There are of course differences. Bethell started writing in her fifties whereas Baker, who is almost fifty, has had a long career as a poet and musician. Bethell’s first collection was published in 1929, Baker’s in 2004. Baker was born in Christchurch in 1968 and has lived in the Wellington region for more than twenty years. She descends from the Ngāi Tahu, Ngāti Raukawa, Ngāti Toa and Te Āti Awa. Bethell, on the other hand, was born in England in 1874, and was of independent means. While she grew up in Rangiora she travelled widely, studying at Oxford and Geneva, and living in London during the First World War. While Baker’s poems clearly show she identifies as a New Zealander, Bethell once stated, ‘I don’t belong anywhere in particular.’

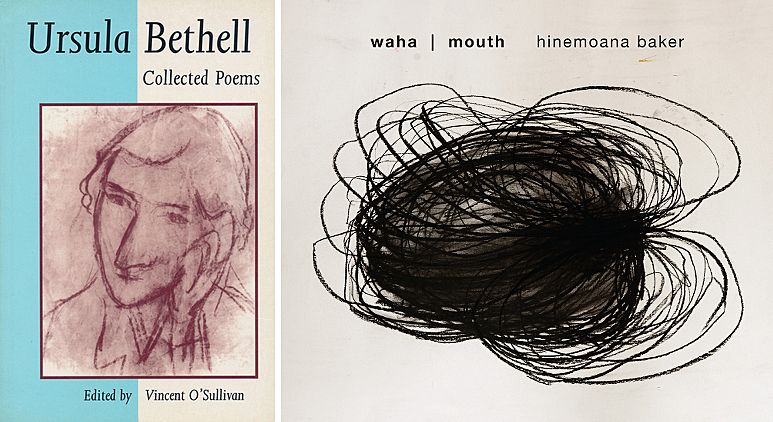

One important difference is the matter of faith. Bethell’s poetry is unreservedly devotional and her poems often adopt the rhythm of a prayer. In the introduction to her collected poems, Vincent O’Sullivan states, ‘Bethell stands with R. A. K. Mason at the beginnings of modern New Zealand poetry. She is also the truest colonial voice that New Zealand possesses, and the most firmly, traditionally Christian.’ After reading waha I had no idea what Baker believed. At the moment she lives in a small apartment in Berlin as the Creative New Zealand’s Berlin Writer in Residence. I messaged her on Facebook:

SJB: Hey. So I have a question for my essay. Do you have faith? I notice a few mentions of prayer and God in your book, but they seemed cultural.

HB: Good question! Just in a ‘believing in something greater than myself’ type way. And believing my dead loved ones were still around me, my ancestors. But one of the surprise side effects of the no-baby journey was that it disappeared. So now? Nothing.

SJB: So you’d consider yourself an atheist?

HB: I don’t consider myself an atheist. It was an involuntary loss, like everything else.

Baker’s poems often move into darkness. In ‘candle’ we see a free diver ‘frogging down from the sparkling surface / to the place where the very water / becomes the sinking anchor tied to your feet.’ In the next section of the poem, Baker’s anchor appears literally as a ‘stone with a muka rope’ that washes up ‘a thousand years later in the shape / of an island white with gulls.’ Both images suggest vulnerability to the elements, and to time. Bethell also notes the way the sea carves at the land. In ‘The Long Harbour’ – a poem about time passing – she describes the way ‘a spent tide fingers the graven boulders, / the black sea-bevelled stones.’

I often encountered these reverberations between their imagery. In Baker’s ‘part 1’ horses represent death: ‘They both died on the same day a year apart / and we all saw the two white horses on the side / of the hill at dusk.’ In Bethell’s ‘Levavi Oculos’ horses become ‘wildness’: ‘the bare hills have a remote wildness, / Like a young colt or filly, unrestrained … Or lying down quiet, knowing nor spur nor rein.’ While their style is different, Bethell often dense, controlled and literal, Baker colloquial, mysterious and figurative, these are poems I feel in my chest. I began to imagine the two women meeting. This sort of imagining made me realise my essay would not be objective or academic, but a response of one poet reading two other poets.

In describing their work, I’m attracted to the metaphor of an anchor – our lives being the boat and mortality the stone, and the constant tension that exists between the two. To read Bethell and Baker is to feel our impermanence: the heavy anchor. In Victorian tradition, Time and Place follows the seasons and our part in those cycles. In ‘November’ Bethell asks us to consider our death, reminding the reader that just as the natural world dies away, ‘presently, thou offerest likewise.’ Bethell sometimes surrenders to the process, as in ‘Forest Sleep’ where she states, ‘Cede separateness … Take root with trees in centuries of decay,’ or in ‘The Long Harbour’ where she calls a burial ground, ‘easy to lie down and sleep there.’ O’Sullivan called these concerns Bethell’s constant struggle between ‘the perceptive woman inside “this ringing cage” of the present, and for the devout Anglican in the ark of her abiding belief.’

Baker’s poems also express surrender. In ‘candle,’ Baker describes the feeling of missing someone as ‘what passes for a lie down.’ Her imagery implies a relief at entering grief. While not explicit, one of the stories running through waha is of Baker’s struggle to conceive a child. It’s a painful thread that Baker evokes through metaphor. In ‘follicle’ the ‘follicle is shown on the screen as black, / a fullness that looks empty’ and which later ‘disappears into its own dark.’ Baker then likens her ability to conceive to gardening: ‘It’s not my strong suit, / he says, gardening. Not my superpower.’

In moments of grief both poets look to the land but also reflect upon themselves in the landscape. In ‘magnet bay farm’, a six part poem set in Banks Peninsula, Baker describes the farm’s inhabitants in celebratory detail: a ‘huge cow / with sharp hips,’ magpies that ‘swoop / at the shiny partings in our hair,’ a ‘Christmas Lily.’ The final section of the poem suggests the ‘feral’ wildness of the farm, in which Baker ‘can be’:

I don’t even have to write about this place.

My body can be an old, soft mattress

in this bay window…

Let’s not mow the thistles, the salvia.

Let it all go feral, let the empty tanks boom at noon.

Let the blowflies and barley grass whack the windows.

Similarly, both Bethell and Baker loved and lived with another woman while writing their poems. Love is the boat that both women sail. Bethell’s inability in the 1920s and 30s to write openly about her sexual relationship with Effie didn’t stop sensual depictions entering her poems. In Janet Charman’s essay ‘My Ursula Bethell’, she observes that ‘the principle of eros’ is instead ‘present in her sensual catalogue of English trees and weather.’ Likewise, in ‘Spring Storm’ Bethell describes, almost erotically, Primavera the goddess of spring:

She arose; with a hand-twist wrung out her tresses,

Her long yellow tresses; flung naked her young limbs,

Her willowy, white limbs, merrily running

And tripping light;

Her burnished hair, tossing, dressed and undressed her.

Describing the goddess allows Bethell some distance from her yearning, whereas Baker’s desire is unapologetic. In the central series of poems in waha, Baker admits, ‘I want to touch my lips on the nape of someone’s neck, breath there’ and observes a young woman’s ‘pale shoulder.’ Later, the woman ‘lies beside me cooling like an engine.’ While Baker can openly write about a ‘cow vagina,’ in ‘Levavi Oculos’ Bethell can only say, ‘A light leaf’s kiss feathers my cheek as it flutters.’ That said, Baker is not immune to society’s expectations, although she rebuts them with humour and ownership. In ‘the adjective game’ a ‘malapropic uncle’ warns Baker:

Darling you better hurry up and get married or you’ll be

Sitting on the mantelpiece poking yourself.

Bethell’s ‘Six Memorials’ written for Effie between 1935 and 1940 are arguably her most personal and important work. These mournful poems were never meant for publication and only appeared after her death. Some academics have portrayed Bethell’s relationship with Pollen as platonic, but from reading the memorial poems there’s no doubt the relationship was a romantic and sexual partnership. Dr Alison Laurie, previous director of the Gender and Women’s Studies Programme at Victoria University, convincingly argues this point, especially in regards to the way Bethell was devastated by Pollen’s death. In the memorial poem, ‘November 1937’ Bethell laments, ‘Left with all this, I lack what made it mine.’ In her sixth and final memorial poem, ‘Spring 1940’, Bethell asks God to relieve her pain:

Match Spring with vision, Spirit of Beauty, bring

With your persuasive love to the inward eye awakening,

Lest looking on this life to count what time has taken

I cannot bear the pain.

The sadness with which Bethell writes about Effie reminds me of Baker’s poem, ‘point the canoe.’ In this poem Baker describes her life with Christine in their ‘green backyard’ on the Kapiti Coast. While Baker describes a thawing in their relationship, the world still slips through their fingers. While they can touch, they cannot keep:

You and I know ice

and how to sing when you’re made of it. We know it takes a year to thaw…

Christine and I scooped estuary mud through our fingers, threw

purple and lime-green sea-smelling weed into the sparkle,

cars drove onto the hard sand and pulled up for picnics.

Through our fingers, blue sky and Central Park in early blossom.

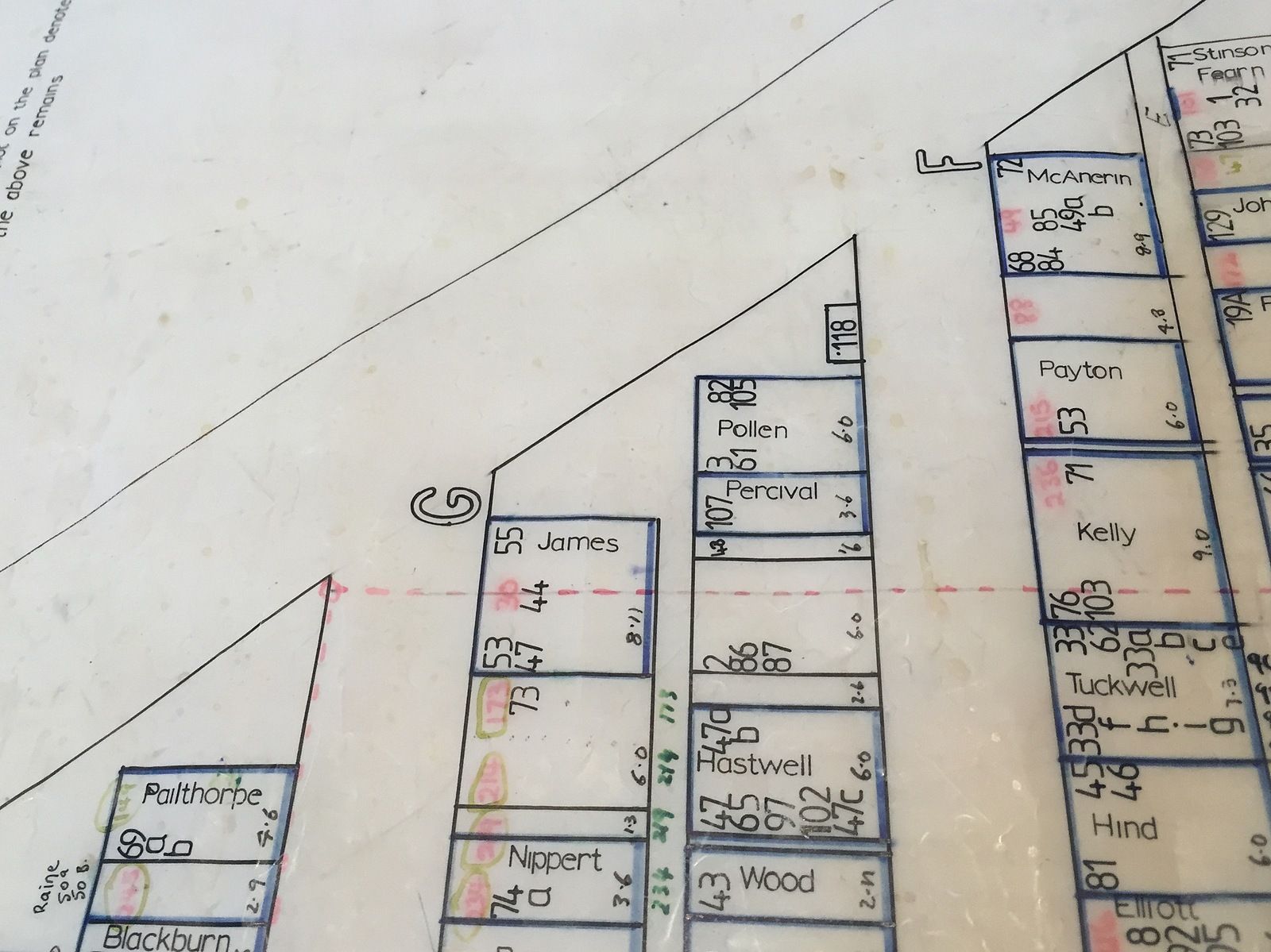

When researching this piece I discovered that Effie is buried with her family in Karori Cemetery, which I can see from my house. It’s across the valley, the rows of stones lined up down Johnston hill. One afternoon my son and I went to find her grave. At the administration office they showed us her plot on a large yellow plan. As we walked the sunny pathways, I thought about the mysterious way poems collapse time. It is clear to me that Bethell wrote because of Effie. She produced most of her poems during their decade of domestic happiness, and barely any after. The memorial poems are exquisite and effecting.

It took us some time to find Effie’s grave. Her name has been worn away and the concrete bed of the plot cracked. On the headstone it simply reads, ‘Effie 1879–1934’. By now Sam had run across the field to the crematorium. It’s a structure clearly visible from our house, which means Effie’s grave should be too, or at least the tree line. She’d been there all this time.

Both Bethell and Baker hold tension in their poems between joy and loss. One evokes the other which evokes the other in a chain of being and undoing. In ‘Weathered Rocks’ Bethell states, ‘Poetry is a music made of images / Worded one in the similitude of another, / Chaining the whole universe to the ecstasies / Of humanity, its anguish and fervour.’ In ‘manifesto’ Baker states, ‘Poetry waits in a crate with a lock. / It raises its head as I enter the lounge. / “Hello my beautiful poem,” I say as I walk.’ We are all locked in our human existence and its many anguishes. Standing beside Effie’s grave I felt a heaviness for the woman who’d lost her, and grateful for the way poetry could let me touch her.