Feeding the Starlings: Six Writers on the Value of Creative Communities

Rebecca Hawkes, essa may ranapiri, Eleanor Rose King Merton, Aimee-Jane Anderson-O’Connor, Isabelle McNeur and Ruby Mae Hinepunui Solly reflect on their 2018 Starling/LitCrawl micro-residencies

What if someone gave you an art gallery to write in for a weekend?

Last year, literary nurturers Starling teamed up with indie festival heroes LitCrawl to offer five inaugural micro-residencies to young writers from across Aotearoa. Rebecca Hawkes and essa may ranapiri (a two-for-one collaboration, bringing total resident numbers to six), Eleanor Rose King Merton, Aimee-Jane Anderson-O’Connor, Isabelle McNeur and Ruby Mae Hinepunui Solly were each hosted by a Wellington gallery over the weekend of LitCrawl, giving them the time and space to write. Here, each writer discusses what the micro-residency meant for them personally, professionally and creatively.

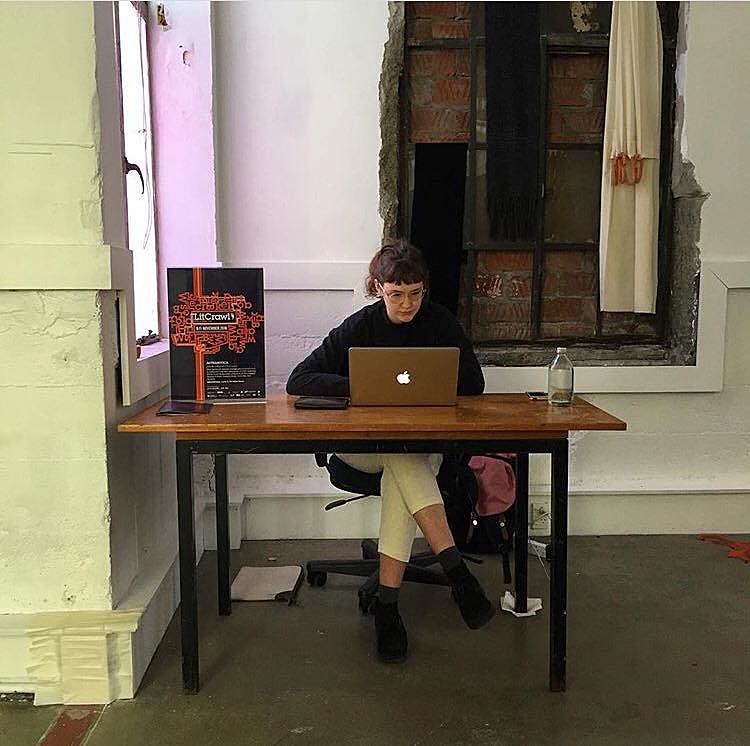

essa may ranapiri and Rebecca Hawkes

City Gallery Wellington

We are inside; glass on either side. We have been given a whiteboard; we have scribbled our incantations on it; prayers to bring in the environmental apocalypse that will surely define our century. We are writing close to water, the jug a threat for laptops. We wet our mouths and dribble words onto pixelated pages, two creatures exchanging the dreams of the lichenthropocene. Drawing up a plan for the future, cultivating imaginary flowers, growing an imaginary garden inside a concrete gallery. Ink bubbling up from the ground, and spreading over the whole weekend.

There we were: two weirdos with a desire to make one shared world to live in, with only our words. The pair of us applied to work on our collection of poems in tandem; a project already several months deep. Trying out this dream exchange, where we make some chimera more than the sum of its parts (and its parents), relied on our capacity to plunge headlong into symbiosis. But we so rarely get to see one another these days. All the good-faith bickering required for our collaboration is stilted through digital channels, where every spoken conversation is an on-purpose call with an agenda rather than the incidentally fruitful shit-talk of idling friends.

So with the micro-residency, it was a relief to have a concrete room to reside in together. A real hard-edged space in which to disagree, to nit-pick, to say, “this isn’t working” – and to compromise, scrawl our incantations of mythic soil and inflorescent apocalypse on the whiteboard, get our hands dirty in the Google Doc garden either weeding each other’s poems or scattering new seeds and helping water them in. Although so much of our project was sparked by other artists’ work (Jeff VanderMeer, Alex Garland, Marianne North, Adrian Cox), our time in the gallery actually helped us find our own firm roots in the project without needing to rely so much on those external sources.

Sharing one room helped us come closer to writing just one project, too. Not two related bodies of work limping along as awkwardly conjoined twins. We needed that intimate physical space to feel comfortable giving our words over to each other. It takes a lot to say, “Here, change this poem I’ve put my soul into, however you like!” No matter how much trust we had in each other’s judgement during our previous remote collaboration, we realised that as a rule it really helps to look someone in the eye as you hand over your latest masterpiece for defilement. And it worked – the pieces that mattered were lifted from the tired old manuscript into a livelier order, cutting out the dead dross to reveal a totally unheralded beast no longer limited by our separate (and equally inaccurate) preconceptions. The project is something neither of us could, or would, have created alone – and that’s kind of the point.

The wider context of LitCrawl was also crucial to the residency experience. Even when not directly collaborating, we draw from everyone we meet, and LitCrawl is a hub of the writing and reading community. The vines draw themselves up and stretch outwards to others in other places, the social world as a mess of spore and trunk. Words refracting into worlds. We emerge from our glass terrarium into the writer’s community as ecosystem. A system nourished by the tireless support of so many people; writers don’t live in a vacuum and this residency showed us that starkly.

Eleanor Rose King Merton

Meanwhile

Four months before my residency, when pressed to provide a summary of the work I planned to focus on, I did the email equivalent of mumbling something about “investigating the geological, domestic and autobiographical”, hoping that by November I would have a better idea of what that looked like. As it turns out, Sophie Bannan and Daegan Wells had already materialised it for me perfectly in their exhibition, Hut for a Sensuous Gold Miner.

Handmade candles in shades of pink and red melting onto the surfaces of the gallery space revealed materials like quartz, gold and flora. It seemed as though Sophie had witnessed my moment of unsure inspiration, taking a note on my phone to “write about the pink and white terraces???” Daegan’s textiles – hand-woven on his grandmother’s loom and hung on ceramics made of clay from the farm he lives on – hinted at how I could escape the rut of repeatedly connecting domesticity to myself and instead how domesticity could be more related to tactility and embodiment.

At the exhibition opening, Sophie offered to send me some material she had been reading while developing the work. We began an email thread that soothed my panic about where to start, putting me back in the academically familiar place of responding to readings. Sophie pointed me to Elizabeth Grosz’s Volatile Bodies: Toward a Corporeal Feminism and Jane Bennett’s lecture ‘Artistry and Agency in a World of Vibrant Matter’ – sources that are conceptually and philosophically broad enough to offer inspiration to people working on projects of any kind, whether it’s a Marie Kondo clear-out, an exhibition, or a very first writing residency.

I came home from the exhibition fizzing about maybe writing an article as a follow-up. By the time a friend noted, after reading the article pitch, “weird to hear u be so posi tho… do u have brain worms”, I was able to articulate how I had been affected by my experience. I was floored by realisations about the work involved in pairing me with an exhibition that so perfectly resonated with my own creative interests, and about how important it is for young writers and visual artists to be connected with each other’s work. I felt more deeply and gratefully about the connections I already have, forged new connections, and understood that the things I’m fascinated by each have their own tendrils entangling them with other potential obsessions and other people’s creative interests.

Aimee Jane Anderson O’Connor

Bartley + Co

The residency provided the perfect Woolfian space to work things out – a change of place and pace, and a big room to throw words around in. With the critical distance that came from being 520 km from my desk, I was able to work through my writing from the past three years and to unlock things that had, up until then, been too close to see properly.

Gallery director Alison Bartley shared her insights into Claudia Jowitt’s exhibition Across Waters – a collection of mixed-media works exploring the coral reefs of the Pacific. I sat down to practice ekphrasis, a way of writing in response to art that I had been keen to try out since attending a guest lecture at the University of Waikato with Therese Lloyd and reading her incredible collection The Facts. I was immediately inspired by Jowitt’s art. Her work is sugar, seashell, masi, coral. I am in awe of her use of found material, and her reclamation of ‘feminine’ pastel colours, her explorations of place and belonging. I wanted to reach out and touch her work, but I couldn’t, and so I wrote her a love poem of sorts.

I realised that my writing is also, in a way, interested in found materials. Sitting there, surrounded by her work, I finally uncovered the unifying thread of my first manuscript: the idea of relics – the things we leave behind, the things that remain.

I think most artists are beachcombers of some sort. Sea salt and sand and slow, short steps. This residency was a great reminder that we’re all out there together. The residency allowed me to meet people who have had an incredible impact on my writing life. It replenished my belief in the value of our creative community, and reminded me that the echo of the blank page isn’t so scary when it’s shared.

Isabelle McNeur

Enjoy

Going into the residency, I had images of sitting in a big, sunlit room with my laptop. There would be a lot of typing and staring blankly at my screen. Over the whole weekend I’d probably have five interactions total, all with café staff when I got something to eat. I did get a lot of writing done that weekend, but that isn’t what I remember most about the residency. What I remember most are the people.

The literary community has always been one of my favourite things about Wellington, and it was in full force that weekend. Being a young writer means I’m still a little at sea when it comes to this scene – but at almost every event I ended up talking with the people next to me, people I vaguely knew from my brief stint writing for Salient or only knew from Twitter. I had a particularly memorable conversation with Annaleese Jochems about how the dog in her book ended up there. A few drinks later, we collaborated on a spontaneous poem to a mailman. Good times.

Fun stuff aside, I feel like there’s something integral about making connections in the literary community – writing is a solitary act, after all, and it can be easy to feel alone in it. The residency provided a gateway to a place full of people who were equally serious and passionate about writing as a craft. Making connections with younger writers who are just starting out, especially, opened the door to a series of truths which are admittedly obvious, but no less relieving to hear: we’re all unsure how exactly we’re doing, or where we’re going, or really much of anything. I’m told this never fully goes away, but I’m sure (at least I’m hoping) it’s more pronounced around this age, where there’s that little itch of worry reminding us that we probably don’t have enough life experience to write, and our brains haven’t technically finished developing until we’ve hit 25, so maybe we should just wait until we turn 30 to write that thing we want to write. There’s a wonderful comfort and camaraderie that occurs among the people finding their way through the same place, stumbling over the same loose rocks and finding hidden rooms.

I recently came across a post online announcing that Aimee-Jane Anderson O’Connor had got a new writing residency, and I went scrolling through the pictures of the fancy flat she’d be living in for the next month. It got me thinking about all the other posts I’ll see as we move forwards, inviting each other to be in zines, circulating new drafts for feedback and watching each other do our thing. The space we’re in isn’t quite where we want to be yet, but we’re wandering through it together.

Ruby Mae Hinepunui Solly

Bowen Gallery

When I step into Bowen Gallery, the irony of writing about back-country Māori men and the ways they teach culture to their children dawns on me. This is a parallel universe to the world I grew up in, and yet here is where I’ve found myself. I remember when I got a bob haircut and cats-eye glasses when I started university. Dad saw my new look and said, “Don’t worry, Rube, they may take you out of Tūrangi, but they’ll never take Tūrangi out of you” – and he was right: I’ll never be a real city kid, because of him.

Bowen Gallery is run by Jenny and Penny, two godmothers of the Wellington art scene. They tell me excitedly about all the artists, and their level of enthusiasm and love for what they do is both nourishing and inspiring. Stepping into Bowen is like stepping into the epicentre of the art scene in Wellington, with people constantly flowing through the two white rooms, stopping to chat with all of us before heading back down the mountain. Young artists, writers, academics, old friends – and people like me, coming across this hidden cave for the first time.

I sit at my desk looking at one of Ans Westra’s favourite pictures, it’s of some weeds by the pavement, and I feel split between feeling at home with an image so familiar, and feeling confused at elements from my life being framed. Seeing what looks like the scruffy pavements of home, on a gallery wall viewed by people whose pavements may never have ever looked so wild. People whose lives may never have ever mirrored the journey of a weed bursting through concrete.

I begin writing a piece about Dad and I, about a time on Ruapehu when he took me inside a snow cave. He wrapped me in his jacket with my eyes closed and only let me open them when we were inside. In my head he had constructed an ice palace just for me; we sit there as it glistens and melts.

I look up and see the white walls of Bowen around me, sterile, but somehow just as homely as that snow cave. There’s a certain comfort that comes from spaces you can’t be in permanently, and a certain unease from the sheer whiteness of the walls. I notice a painting by Euan Macleod: a man traversing a mountain, his face blurred by shadow and snow. Turns out you were fine art all along, Dad, right here in the cave.

The 2018 LitCrawl/Starling residents would like to acknowledge the hard work involved in making these experiences possible. Thank you to Francis and Louise from Starling for their championing of emerging writers, to Claire and Andrew for their tireless work in ensuring that our creative communities have festivals to gather at, to the patrons of the residencies for the material support so often missing from the arts, and to the staff and artists of the participating galleries for being open to a new thing.

Read some writing produced during the micro-residencies in Starling Issue 7.