Conversations with Four Artists of African Descent

Makanaka Tuwe claims the narratives, traditions and cultures of musicians of African descent in Aotearoa as the centre.

Music and sound composed by people of African descent have a long legacy and influence worldwide. Trace any genre: hip hop, pop, rock and roll, country, reggae, and the roots point to a Black music tradition. In 2020, I pulled together a playlist with artists of African descent who reside in Aotearoa. I noted that everyone was tapping into a sound and influence particular to a region or group.

In the following conversations, I chat with Nuel Nonso, leader singer of Ijebu Pleasure Club, who is Igbo from Nigeria (West Africa), and singer–songwriter Audrey Apollo, who is of Burundian descent (Central East Africa). I also spoke with saxophonist Thabani Gapara, born and raised in Zimbabwe (Southern Africa) and upcoming musician Jujulipps, born in South Africa (Central, East and Southern Africa), whose parents are Congolese and Burundian.

In our conversations about their music and the influences that inform their sound, we kept coming back to language. As Audrey noted, singing in one’s mother tongue feels like you are time travelling. Not only is music something that connects us to our history, the language, rhythms and unique compositions do too.

Trace any genre: hip hop, pop, rock and roll, country, reggae, and the roots point to a Black music tradition

This made me think about how storytelling and the oral tradition is central to African cultures as a tool for knowledge production and transmission. In West Africa, a griot plays the role of storyteller, singer, musician and oral historian; they are a living archive of the people’s traditions. Our storytellers in Shona (Zimbabwe) are nyanduri, imaginative thinkers skilled at telling stories.

In a world where whiteness superimposes itself as the default, it is important that our stories not exist as counter-narratives, as that is whiteness centring itself again. We have our own centres, frames of reference; rich, expansive and deep wells of influence and inspiration to drink from.

Being in conversation with these artists and noting how rooted they are to where they come from gave me goosebumps. It reminded me of what Toni Morrison said about claiming her centre and creating from that space.

"I stood at the border, stood at the edge, and claimed it as central,” you said, your voice weighted with intent. “Claimed it as central, and let the rest of the world move over to where I was.”

There is power in naming our centre, in claiming our narratives, traditions and cultures as the centre of our world and how we see and engage with it. My hope is that these conversations are an insight into the diversity of African cultures and the depth of Blackness. As Nuel reminded me, there is so much about ourselves and each other that we are still learning.

The musicians I’ve chatted with are all based in Tāmaki Makaurau. I hope in future to speak to other artists of African descent across the motu.

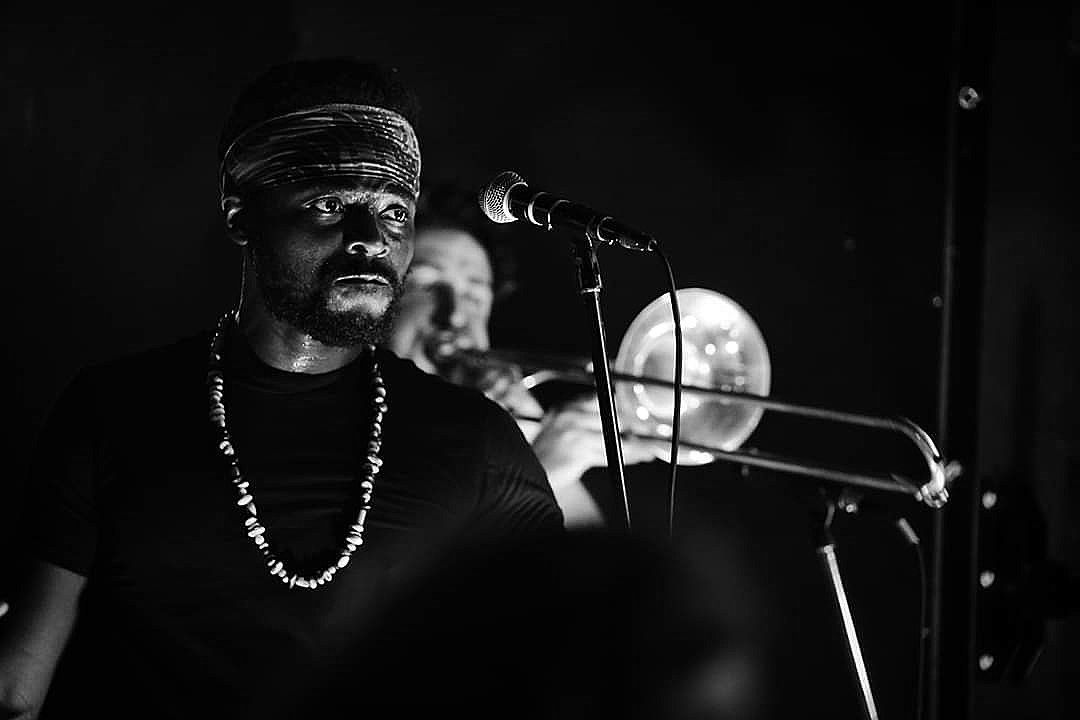

Image credit: @samuel_richards

Nuel Nonso

MT: I know you’re a part of Ijebu Pleasure Club, but I was wondering, where did your journey with music begin?

EN: My first foray into music was as a boy-band member with my brother and a friend at university. We had this Afro–RnB, Afro–soul thing going on that was influenced by Boyz II Men, Take6, and Nigeria’s Styl-Plus and Plantashun Boiz. We performed a few times on campus and recorded demo tracks we never finished. I also sang in the choir in church till about adolescence.

About six months after I arrived in New Zealand, Ijebu Pleasure Club was born. I wanted to connect with other musicians and I hopped on Meetup looking for a band. I met up with Ben, and when we spoke about influences I listed the previous artists I mentioned, plus Femi Kuti. I know everyone is obsessed with Fela Kuti, but I’ve been a huge fan of Femi Kuti [his eldest son] since I saw him perform in Lagos.

It turns out Ben was previously in the Afrobeat band Zoh Zoh, which was led by Yaw Boateng. In our conversation, we spoke about Fela Kuti’s music being the most recognisable in terms of Afrobeat, as he is the father of the genre. As a band, if we wanted to pay homage to the genre, we would have to play his music.

In a world where whiteness superimposes itself as the default, it is important that our stories not exist as counter-narratives, as that is whiteness centring itself again

MT: It’s so interesting that one of Ijebu’s founding members played with Yaw. ZohZoh used to host some sick live sessions at Nectar Bar! I’ve always wondered, what does Ijebu mean?

EN: Ijebu is a place in South-Western Nigeria. It’s close to Lagos, the most populous city in the country. Wherever you live in Nigeria, there is the staple food of garri. Garri is cassava flakes, and while you might have heard of Nigerian fufu, garri is more a staple than fufu is. There’s a debate about whether fufu should be the umbrella term for everything of that doughy consistency that is eaten with our soup, which I’ve been told (in New Zealand) is stew. The garri is the staple everyone has at home, and Ijebu garri is nationally considered the top-tier garri for soaking or drinking. When I say drinking, you put the garri in cold water and add sugar and milk.

MT: I get it. It's kind of like how you’ve used fufu as an example of something that everyone knows (even outside of Nigeria). So in this instance, Ijebu garri is a vital component that contributes to the rich culture but is more-localised knowledge.

EN: Exactly! It’s the staple that everyone has, it's not your fancy stuff, but you need it. It’s essential.

My first love is between traditional Igbo rhythms, soul and hip hop. Growing up, there was Stevie Wonder, Fela and Celestine Ukwu

MT: You mentioned you love Femi Kuti and were influenced by Plantashun Boys and Boys II Men. Are there components of any other sounds and genres, spaces and tastes that make up your sound?

EN: My first love is between traditional Igbo rhythms, soul and hip hop. Growing up, there was Stevie Wonder, Fela and Celestine Ukwu on the radio, and sounds that have never been heard outside of Nigeria. So it feels like they were fed in simultaneously.

In terms of harmony, it was the artists I previously mentioned and Destiny’s Child. It’s African American harmonies that I traced back to Negro spirituals. Then when it comes to rhythms, it’s traditional Igbo rhythms. Those are the sorts of influences I draw from, a huge chunk from Amawbia (Mum’s cultural subgroup) and Mbaise (Dad’s cultural subgroup) sounds. My mum would often sing songs that she sang in her troupe growing up. These include some folk songs that I can sing, and when I forget or when the imagery used in the language is too dense for me to unpack, I video call her and ask her to remind me.

I also draw inspiration from the use of language, and because I didn’t grow up speaking Igbo at the same level that my mum would’ve as an adolescent, it feels like poetry. I love poetry, and I’m always trying to translate the way imagery is used in Igbo into English, to see the similarities and differences. I found that, at times, there isn’t a poetic attribute to a word we have in Igbo [when translated into English] or even a way to convey the same feeling and imagery. So, for me, it's not only the sound; it’s the lyrics, the rhythm and the harmonies coming together, making something different and familiar.

You’re absolutely right, our languages are so poetic, and I don’t think the English language has that range

MT: You’re absolutely right, our languages are so poetic, and I don’t think the English language has that range. Our languages open up a whole world, and that world can be used to fill in the layers of a sound or what someone offers. I also think what you’re doing with your music – and pulling together sounds that are different and familiar – is embodying the Akan notion of sankofa, which is going to the past to retrieve knowledge – in this instance, language, sound, rhythm and harmony – to inform and bring it into the present. Now, when can we expect some music from you?

EN: It’s a work in progress. The idea behind it is to comment on the jarring union between traditional African and Indigenous cultures worldwide, and the colonial cultures that have been superimposed on many of them. The idea of straddling both cultures, negotiating the notion of being, and making sense of it in the awkward space between. Seeking the meaning of your traditional culture in an alien language, the awkwardness of all that. It will be reflected in the language I’ll use and the sound of the different genres. They sound like they don’t fit in together but, somehow, they belong.

Image credit: @brickandjim

Audrey Apollo

MT: Is there a story behind your artist name ‘Audrey Apollo’?

AP: Audrey is my birth name. When I came up with Apollo I wasn’t Christian yet, but Apollo is the Greek god of music, poetry and light. When I chose that name, I was going through a time where I chose life and owned who I was. I decided not to look at my love for jazz, art and poetry as these weird things, but to see them as my gift. I feel like gifts aren’t exactly what culture would tell you they are, and the most common ones are categorised into arts, society and politics, but the gift of communication is also a gift.

MT: I love the infusion of Greek mythology and the connection to your gift of writing and sharing your light. You’re also right about gifts, our gifts show up in the characteristics that we embody, and communication is storytelling, an art form. In your latest release, ‘Wanstead Way’, I can pick up on themes of loss in what you are relaying. What is the song about?

I decided not to look at my love for jazz, art and poetry as these weird things, but to see them as my gift

AP: ‘Wanstead Way’ is the name of the street that I recorded the voice memo on, so when I sent the track to the producer, that was the name that came up. It was supposed to be titled ‘Tears at a Tea Shop’ and was about the first time I cried in front of my mentor, a moment when I met myself.

I found myself in a position where I was coming to terms with the fact that my father was no longer in my life. Being the eldest in a family from where we are from, living in Aotearoa, that is quite jarring.

A lot of people thought it was about a romantic interest, which is fair enough, but it's about my dad and the conversation I had with myself after I had healed and no longer hated him. I now empathise and understand that he is not just my dad. He is a random human who endures, suffers, rejoices and celebrates. But at the age of 15, witnessing him go from superhuman to human was something else.

The line “Maybe I am just a fool for loving a man who never stayed long enough to tell me he loved me too”really dissects the relationship we had. In saying that, I can absolutely say he loved us and took care of us in the way he was shown how to. It was what he knew and the best he could do, and I can’t hate him for that. I sometimes think that ‘Wanstead Way’ is actually a happy song for me, because it was the end of a chapter I had been holding on to.

We ended up calling the track ‘Wanstead Way’ because the song is quite heavy, and if you sit there and read it line for line, it’s a poem at heart.

My earliest memory of music is growing up listening to gospel and reggae

MT: Thank you for sharing your experiences and how they informed ‘Wanstead Way’. Having an insight into your experiences also puts the ‘waning’ in Wanstead, and the idea of a waning moon, where its visible surface area is getting smaller. It’s the time in the lunar cycle between a full moon and a new moon, where it feels like something is being released, but you’re also creating a blank canvas for what’s to come.

Listening to ‘Wanstead Way’, I heard a call-and-response element quite typical of traditional African sounds. Then I went on your Soundcloud, played ‘Eighteen’, and heard a hymn. You’ve sung it in Swahili, but we also have a Shona version of the same hymn. Hearing these elements in the two songs made me wonder, what part does your cultural background play when it comes to your music?

If anything was playing in the house, it was Bob Marley, Joyous Celebration, Aretha Franklin or my mum

AD: Every aspect, to put it simply. My earliest memory of music is growing up listening to gospel and reggae. If anything was playing in the house, it was Bob Marley, Joyous Celebration, Aretha Franklin or my mum. My mum is a big part of why I’m involved in music as she was always singing and teaching me how to dance, whether it was to Koffi Olomide or Fally Ipupa.

When I became a Christian and got into contemporary worship, I started re-listening to the gospel songs that my mum used to listen to. I started going to African churches, and the way they play these contemporary worship songs is different [to Western churches]. It felt so familiar, and the sensation I experienced down my back was out of this world.

Now when I step into the influences that you hear on ‘Wanstead Way’ and ‘Eighteen’, it is me learning music and learning about music from where I’m from. Out of all my sisters, I speak Kirundi the most, and when I say I’m influenced by the language, it's because when my mother and her friends sing this music, it feels like you are time travelling.

When my mum first taught me the hymn in ‘Eighteen’, the power had cut, and the power cut often at that specific time in our lives. My mum always did two things: we would play Word Find, or she would sing us these songs.

They're singing in this nostalgic sense, singing because they are mourning and missing their parents. They are singing because they remember how amazing it was and they're singing because at lunchtime that’s what they did with their friends.

When my mum first taught me the hymn in ‘Eighteen’, the power had cut, and the power cut often at that specific time in our lives. My mum always did two things: we would play Word Find, or she would sing us these songs. At the time, I didn’t understand the lament in her voice – she was not only a child in the living room with her mother, she was now a mother watching her children and thinking if there’s only one thing I can pass down, it will be the love of music. It carried her through a war, through immigration, and her divorce. These are ground-breaking moments in her life that I now tap into and carry through depression, anxiety and bullying, and I know there’s one thing I know how to do. And that’s singing.

Image credit: @synthiabahati

Thabani Gapara

MT: I’m gutted I missed your gig the other night – how was it? How does it feel to engage and connect with people through music during this time?

TG: The gig went well, and it was really cool that there was an audience who wanted to check out some music. It’s a reminder for folk in the music industry that people want to hear the music or the interesting ideas you are making. Maybe you are not playing for 10,000 people, but the intimacy associated with people choosing you and the music you make is a great thing for the art. It's great for the person appreciating the art, because they have a space they can come to and have an intimate relationship with the music.

Going forward, this is a great format for people like myself, who are trying to develop an audience for the art they are making. It’s made me reflect on the relationship between performer and audience, that direct connection. We have an industry on the commerce side that has made it, “I must sell records, I must be viral, I must trend.” The relationship has become one of a performer and a spectator. In some of the research studies I’ve been reading on traditional music from home,* I’ve become aware that the relationship between performer and spectator or audience does not exist in the traditional music setting in Zimbabwe. The relationship is between performers and participants. The audience member is an active participant in the performance.

The relationship between performer and spectator or audience does not exist in the traditional Zimbabwe music setting

If you look at mhande – a Karanga style of music – and a song like ‘Dzinonwa Muna Save’, it’s a participatory experience. You can’t be an audience member and just marvel at the talent; the whole point of this piece of music is participation. You sing along, you clap, you ululate, you dance, and there’s an engagement. The audience participates in setting the energy in the space.

MT: It’s so interesting you said that, because I was talking to Audrey about the use of hymns in her music and how it reflects the African tradition of call and response. What a beautiful way to articulate the intention you set out of participation in your performances. What sort of material have you been performing?

TG: The show I’ve created presents music from my first original record, ‘The Griots Path’. It’s been fantastic getting to play the music. The second half of the show is a combination of ‘In Their Footsteps’, a live-session recording I released in 2019, and music that’s forthcoming. Essentially, the show is what has come and what is to come. It's been fun sharing the stories behind the music. Because it’s instrumental music, people get to form their own ideas or imagery connected to the music.

If you look at mhande – a Karanga style of music – and a song like ‘Dzinonwa Muna Save’, it’s a participatory experience

MT: What would you say is your favourite story to tell?

TG: They all have a special connection to me, so one doesn’t stand out from the other. For instance, there are two new songs, one of them is ‘Mai Mwana’, which is an ode to my mother, and mothers. Then there’s ‘Matunga’, my totem, and specifically for the fathers in my life. So I can’t say I like one over the other.

MT: I feel for you, especially – each song has its own place in your life. What is your writing or creation process?

TG: The music that I make is highly collaborative in nature. I’ve never experimented with recording first and then having the band learn the music for performance purposes. I enjoy giving people music, and then we play the shit out of it, then we record. I’ve spent the last year writing an album worth of music, and I don’t expect to play it for another year, and to record it a year after that. The distance between creating a piece of art and sharing it is valuable.

What would you say is your favourite story to tell?

MT: I hear that. It gives whatever you’re working on space to breathe and form a personality without the rush. Giving it that space to breathe allows the thing to express itself how it wants to.

TG: Yes, and for you to be at peace with it being whatever it is.

MT: When I first started talking to you about your music, your aim was showcasing Southern African jazz, has there been a shift?

TG: It’s still showcasing the sound of Southern African traditions through the lens of a jazz musician. It is Bantu music informed heavily by jazz traditions and sensibilities, following in the footsteps of so many jazz greats who’ve come from the African continent.

It’s very mwana wevhu, son of the soil vibes, and I feel that is something people from Southern Africa would feel

MT: I love that! To say its Bantu music informed by jazz speaks to how Southern African jazz came to be, through the interaction of so many different cultures and things coming together.

TG: It’s very mwana wevhu, son of the soil vibes, and I feel that is something people from Southern Africa would feel. As I mentioned earlier, I’ve spent the last year writing music influenced by traditional Zimbabwean music. I focused on mbira, mhande, mbende and mbakumba, and hopefully people can hear the connection. I am still pursuing making music that has a strong sense of place, and that place is definitely very Southern African, but every other thing that I play is also allowed to exist in there – pop, funk, reggae.

*Thabani and I were both born and raised in Zimbabwe.

*

MT: I want to start by saying I love your name! Why Jujulipps?

JL: Thank you! I’m happy you asked because this name is a double entendre. I was born and raised in South Africa and moved to Invercargill, New Zealand, when I was about 12 years old. Imagine moving from South Africa to Invercargill – it was so different! I had just started school, and this kid looked at my lips and asked, “Why are your lips like that?” I remember being surprised because I love African features, especially mine. So he goes, “Your lips are like jujulipps,” and he made this little joke. I wasn’t necessarily hurt by it, but I remember noting that that was the first time in my life someone had said that.

As I got older, I figured, let me reclaim this name and make it mine. It started as an insult, and I’ve made it my own over time.

I had just started school, and this kid looked at my lips and asked, “Why are your lips like that?”

MT: I love a bit of reclamation! Especially when non-Black people are blackfishing. People are getting their lips filled, using makeup and various enhancements to look like us, to get features we are heavily discriminated against for having. Anyways, what does Jujulipps mean to you as an artist? What does she personify?

JL: In a nutshell, Juju is confidence. When I make music, I want people who listen to it to feel confident in themselves. With the name Jujulipps, I’ve never been ashamed of the way I look or my African features. If anything, it’s my favourite thing about myself. With that name being such a statement of standing up for myself, it encompasses everything Jujulipps is. It’s confidence, because it's very easy to be led astray. We weren’t a trend ten years ago, cornrows were being made fun of, and now it's a thing that everyone wants to partake in.

MT: You’re absolutely right about standing in our power, and recognising that this is who we are and not waiting for validation. It’s interesting that you mention confidence, because I was first introduced to you after you released ‘Hilary Banks’. I remember pausing the track after a few seconds because I realised I needed to put the bass on high. All I could think about was the fierceness that is Hilary Banks. Is there a story behind the track?

As I got older, I figured, let me reclaim this name and make it mine. It started as an insult, and I’ve made it my own

JL: As well as confidence, Jujulipps is hype. Those two things go hand in hand. For my personal practice, affirmations are very important; I start my day with them. One day I was looking in the mirror, and I looked really good. So I looked at myself and said, you look like Hilary Banks, a million dollars! That same night I got sent the beat, and I was still in that zone of feeling myself. It’s probably the fastest track I’ve written. ‘Hilary Banks’ feels confident, feels hype, and wants other people to feel that.

MT: I love that, and I love that you have a practice of affirming and praying over yourself. It’s interesting how the things we do to ground can inform what we do. Apart from affirmations, is there anything else that you do to support your creative process?

JL: Everything I do creatively is based on life experiences. I always have a notebook with me and you’ll find me writing a rhyme or a few sentences throughout the day. What I write is on the less formal side of poetry. I also find collaborating with people that know me and understand my vision grounding. It’s very important for me to have African women around me in every aspect of what I do. Even having them in the studio writing or producing with me, that is so dope. It gives me a homely feeling!

As well as confidence, Jujulipps is hype

MT: That’s really beautiful, we love to see it! Who would you say are your musical influences, and what sort of sound inspires your sound?

JL: That’s a hard one because I’m inspired by everything due to my cultural upbringing. My father is Congolese, my mother is Burundian, and I was born in South Africa and raised here. My main influence would be Nicki Minaj because that’s what I grew up with. In saying that, I try not to make my music specifically hip hop, and if there’s any chance I can integrate some African influence, I do. Right now, I’m inspired by DJ Maphorisa, Rico Nasty and Sho Madjozi, not just musically but their looks and personas.

MT: I can hear the Rico Nasty influence at the beginning of ‘Hilary Banks’. That’s so awesome to be able to pull from a massive pool of inspiration and have that global lens in your music instead of boxing yourself in.

JL: I always speak about not wanting to be boxed in. I don’t have a massive catalogue at the moment, so it's easy for people to put me in a box. I’m super excited to be releasing projects that show my extensive skill set, because when you are a child of immigrants you naturally have so many influences, so it's difficult to box us in.

Feature image: Nuanzhi Zheng 郑暖之。