Speaking to our Private Selves: Into the River

Teenagers have the right to choose their own literature, and we have a responsibility to let them.

As a teenager, I was a voracious reader for many reasons: deep curiousity about people; eagerness to learn; wanting richer connection to a world of ideas; readiness for some subjects that adults around me hadn’t clicked I needed to know about yet.

I read to know that I wasn’t alone: I loved books about slightly overweight, overly sensitive, outsider kids; but I also loved books about characters in utterly different circumstances and even other worlds. I read science fiction, fantasy, realism, comedy, poetry, drama, comics and more. I read to think through ethical questions and I read to have adventures that I knew I was too timid to have in real life. I read to understand my own mistakes. I read as a way of placing a glass to the walls of my own home; to sound out the internal creaks, sparks, tensions. And also as a way of recognising my own great good luck.

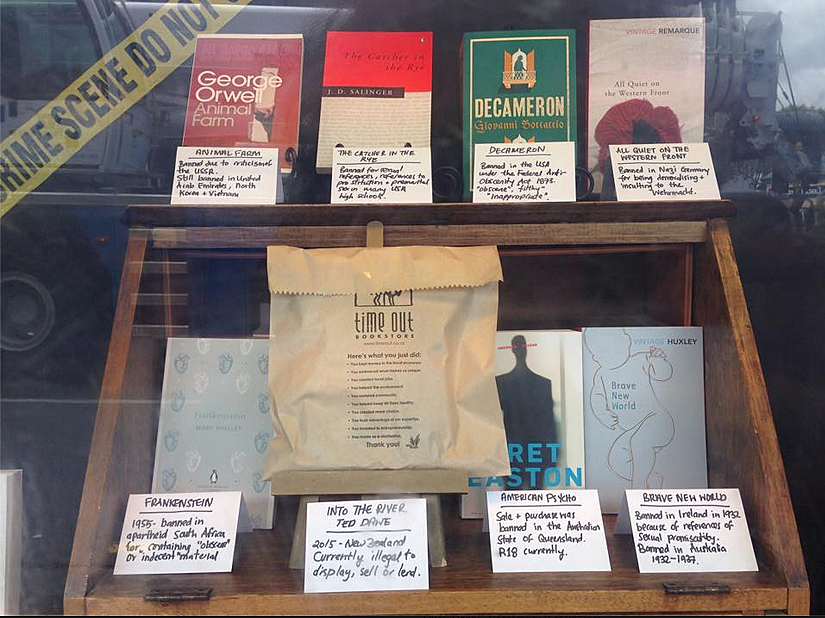

Last week, I had expected my days to be given over to the hectic nerves and turbulent happiness of launching a poetry collection. Instead, I was blindsided by the feeling that writers and editors needed to defend the nation’s very right to read. I was so stunned to hear about the interim restriction order on Ted Dawe’s Into the River that I thought public dissent was imperative.

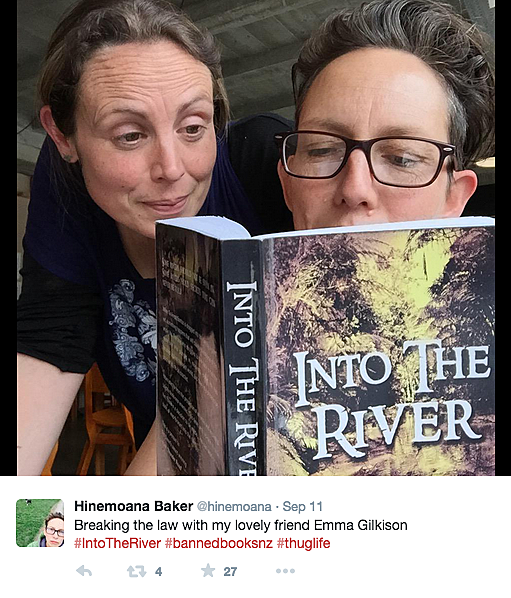

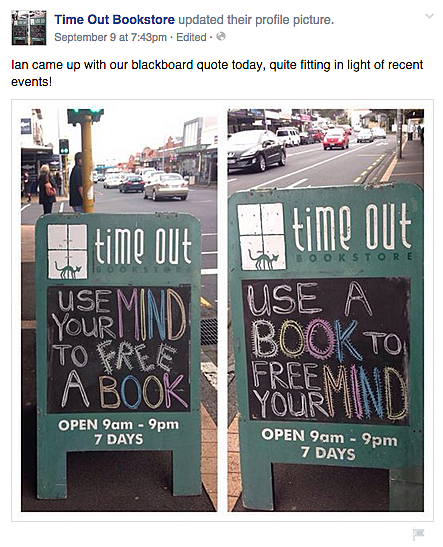

I wanted a visible way to draw attention to how ludicrous and unjust the situation seems, without breaking the law. Sale, loan or display of the book is forbidden temporarily, yet if you already own it, it’s still legal to have it for personal use.

This novel is not injurious to the wider social good. It neither incites violence, encourages hate, nor qualifies as pornographic. Even an interim prohibition seems irrational. (Mathieson, president of the Film and Literature Board of Review, demurs from the word ‘ban’, saying it’s emotive. I disagree; I think it’s merely descriptive.)

What would the authorities do if people gathered together to read their own copies, silently? It would be a demonstration that was at once peaceful, wry, absurdist and defiant. Nobody can tell what you’re thinking when you read quietly to yourself. (As UK writer Jenny Diski shows in her memoirs, it can be seen as an almost maddening act of self-containment and independence.)

Wellingtonian Susan Pearce and Aucklander Alexandra Balm liked the protest idea and decided to hold simultaneous silent readings in public solidarity for Dawe too. Other national and international readers contacted us to say they’d bought the book (before the ban took effect on Amazon) and would join us in spirit in their own homes and time zones.

I counted about 50 people at the Dunedin turnout: impressive for midday on a Thursday. (Media attending gave estimates ranging from 35 to ‘over 40’.) Among the protestors were academics, general staff, students, secondary school teachers, writers, editors, bookstore staff, former publishers, council staff, and other members of the public. People who didn’t own Into the River read other Ted Dawe novels, or previously banned books, ranging from Ginsberg’s Howl to Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland. I gave six media interviews that day: it was surreal and slightly scary. If this restriction order could muzzle Dawe’s prize-winning novel, could we be arrested for openly reading it? No uniformed police showed up, though there were a couple of suspiciously well-dressed senior men who swooped in and watched us hawkishly from a distance. (Threaten civil liberties, and this climate of paranoia is born…)

Why defend Dawe’s book? Because it has significant literary, social and cultural value. Because it confronts racism and bullying, and is directed at a traditionally reluctant readership (young males). I’m not the target demographic, but I strongly believe in freedom of expression and access to ideas — as enshrined in the UN Declaration of Human Rights. Teenagers might need guidance, or forewarning that a book’s content is explicit or disturbing, but preventing young adult and adult readers from accessing this particular book, even temporarily, is extreme.

Reading itself is a form of liberty. As the NCTE Executive Committee in the US says in their guidelines, ‘The Student’s Right to Read’ (November 2012):

In effect, the reader is freed from the bonds of chance. The reader is not limited by birth, geographic location, or time, since reading allows meeting people, debating philosophies, and experiencing events far beyond the narrow confines of an individual's own existence.

The threat Family First sees in rich, imaginative fiction comes clearer in the light of that statement. If young people have the liberty to think, judge, criticise, and develop the powers of debate, argument and analysis, they are more resistant to dogma and religious inculcation. I’d emphasise here that reading a broad array of books is key.

Literature help us see various sides of a debate and to consider the rightness or wrongness of a reaction – in essence, develop an opinion. Reading hones our decision-making skills. It keeps us intellectually and creatively limber: two things we must be, in order to cope with change, pressure, and daily responsibilities.

As I’ve written elsewhere, I strongly believe that literature is one of the places that young people can safely think through situations, and rehearse their moral choices, without the grave personal compromise that living through the real events might involve. When I read an early draft, I thought the novel was aimed at ages 15+: the sex scenes are unromanticised, and speak the truth of unsatisfactory experiences. They happen in the context of a young, disenfranchised teenager trying to grapple with a loss of identity and with institutionalised racism, individuals’ racism and classist attitudes; with a life where the moral compass seems skewed to those with a dubious authority. The main character, Devon, is left hurt, bewildered, empty, and wanting more than the casual encounters he’s had. The real tragedy is that Devon has nobody to talk to about what happens to him. He’s deeply isolated. The hunger for something wild and explosive that grows out of his failed relationship with the first teenage girl he has sex with – the craving for anarchy – is a channeling of pain and inarticulacy.

Is there any truth to the Family First claim that this kind of hard-hitting, sexually frank fiction can harm our young people? I don’t think so. Research shows that teenage pregnancy and STD rates drop dramatically when young people are given good sex education. We already have lessons about the facts of reproduction in schools; what we’re not so good at is discussing the complexities of intimacy; about respect within a relationship; about anyone’s right to say no and not be pressured into sex. Explaining and exploring the intricate, messy stuff of personal relationships is where subtle imaginative fiction has unsurpassable strength.

It’s this nuanced quality of fiction that makes Malorie Blackman, the 2013–2015 UK Children’s Literature Laureate, argue that teenagers desperately need honest sex scenes in their literature so that they see a more realistic version of intimate relationships than the often degrading, brutalising view shown in porn. Good fiction shows us consequences the way porn and music videos so often don’t.

Representing certain behaviour in a novel doesn’t necessarily mean condoning it. It seems Family First have misread the novel’s tone. The depiction of sex, drug-taking, the manipulative and exploitative teacher: none are portrayed in ways that incite, encourage, or egg on the reader to play copy-cat. (Hey! Get involved with a creepy teacher! Not.) The book is a layered, cautionary, utterly non-patronising portrait of a young boy trying to handle various influences and situations without close family backing; without the moral guidance of good adults; without the cultural insulation of his own whānau nearby, supporting him in dealing with noxious influences.

The book helps us to see how someone can ‘go off the rails’, as the main character, Te Arepa/Devon Santos does in the sequel, Thunder Road. An important thing to understand about this book is that it grew out of readership demand. Young people who loved Thunder Road wanted to know what made the drug-dealing, risk-taking, charismatic Devon Santos the way he was. Into the River gives us a detailed, heart-breaking answer, which turns around to point the finger at all kinds of adult corruption.

How can raising and exploring these moral issues with the careful yet honest hand that Dawe does harm readers? It is orders-of-magnitude different from music videos or porn films where graphic imagery exposes the viewer to highly sexualised, often glamourised, violent, exploitative content without any insight into character development, or the participant’s interior response. (Or indeed to a sense of, say, the economic, educational and gender inequalities that might have led the porn actors/models to their ‘career choice’.)

The American poet Denise Levertov has written about the horrors of the failure of imagination in a social context like Nazi Germany. That failure is the inability to see that ‘we are members one of another’, as she says. I think a vivid and sensitive imagination forms the well-spring of an ethical society.

Yet I’m a middle-aged, white, cis-gendered woman: I’m not the main target readership for Dawe’s book. So I put some questions out to about 30 young people in my orbit: who ranged in age from 13 to 25, and who come from varied cultural and social backgrounds. (Pasifika, Eastern European, NZ-born Pakeha, South African, queer, bi, straight, undecided, Christian, atheist, agnostic.)

The answers reminded me: never underestimate young adults. One response, from a university-age student, was sobering. It was inadvertently an argument for just why we need to encourage teens to read, critique and question a truly diverse swathe of books, including gritty social realism like Dawe’s:

I was always looking for romantic adventure novels, especially in crime fighting capacities. I do wish I had not read as many, however, because it gave me a very one-sided view of what a relationship is like and I was honestly primed for the ‘tall dark handsome’ stereotype. Because I was primed to believe that all relationships should include a tall, dark and handsome man, minimal drama, all leading up to that one kiss before the novel ends, I ended up in some very bad and abusive relationships because I couldn’t see past the stereotype.

Here, harm has been done not by frank and honest, psychologically accurate fiction, but by narrow reading in a genre trench. It’s vital not to shut down other literary flight paths; vital to encourage close reading and critical analysis.

One 14-year-old girl (for whom English is a second language) said she once came across a manga comic that she initially thought was relatively innocent; but the violent content meant she stopped reading it. She wished it had a warning sticker, suitable for age 21 +. Yet she didn’t think it should be banned. Instead, she argued that teenagers should be advised, yet still have the right to choose and to self-censor:

Everyone is different, even people of the same age and blood. Some teens could handle adult theme books while some people could only handle softer and gentler things. When it comes to books, physical age is not an object, but the mentality of the person is. Just because most teens' favorite colour is blue, it doesn't mean that everyone of that age likes the colour blue better then any other colour, and the same thing is with books.

She also said, disarmingly, that while she’d never broach some subjects with her parents because they’d get too emotional:

books do give me courage to ask my parents about some things, such as politics, and I think books shaped a fraction of feelings for my parents (mostly about love and how precious they are).

Another answer made me think this new generation has so got our number already. When I emailed questions, I didn’t mention the current book brannigan. Yet one 14-year-old boy wrote (with my questions in bold):

What sort of books do you love reading?

I enjoy reading the Bible, and reviews from FamilyFirst.

What do you hope to get from a book?

I hope to hear about conservative messages, telling me to do what I've been told and not anything that might "operate as a semi-precedent, and […] exert a significant influence upon other decisions portraying teenage sex and drug-taking" because that would be bad and my right-wing Christian parents wouldn't like it.

Has anything you’ve read ever upset you so much you’ve wished adults had protected you from it? (Can you name the book?)

Into The River by Ted Dawe made me really, really sad. That's not what teenage boys are like!

Do you believe adults should say what you can and can’t read? Or should they just advise you so you can make your own choices?

Mother, or in this case Bob McCoskrie, knows best.

Do books sometimes help you discover ideas you would be too embarrassed to talk to your parents about? Is that a good or a bad thing? Alternatively, do books help you work out how to talk to your parents about some subjects?

I don't get what you mean. I tell my parents everything!

Just in case I didn’t understand, he helpfully headed that set of answers ‘ironic’. Under a separate heading, he sent genuine answers as well.[i] But the satirical set had already taken the cake: and shown grandma how to eat it, too. I really do think that in the case of Dawe’s novel, the kids will be all right.

Though it’s been some time since I was a teen myself, I still believe wholeheartedly in the worlds that books can offer. Fiction is a vital tool for measuring and understanding experience: friendships, physical development, aspirations, attraction, family, social divides, the raft of things we become so much more actively conscious of in our teenage years.

Sometimes, even if you have close confidantes in family or friends, there are topics it just feels easier to confront on the page. Non-fiction books about issues like bereavement, illness, relationships, can be invaluable supports at certain points in our lives. Yet there is also only so much that non-fiction tells us. While it equips us with a myriad of facts and advice, its role isn’t to capture how particular troubling and mysterious experiences feel. This is the realm of fiction and poetry. They speak to our private selves. And when that private self is nourished, it’s better equipped to deal with the social world, too. Love, grief, betrayal, disappointment: seeing how fictional characters react can be a kind of trial run, perhaps even a form of psychological immunisation. Reading of a character’s approach mightn’t reduce the intensity of our own experiences, but it can still lend clarity and perspective. Someone else has put what we feel into words: and in language that captures ambivalence, complexity, the pitch and tilt of feeling.

Reading is the closest we can get to living inside someone else’s skin; slipping into their imaginative inner life. The intimacy is much closer than when watching film; and our own imaginations are given more independence. So fiction has the perhaps paradoxical effect both of strengthening our interior worlds, and of helping us practice empathy: allowing us to understand what it’s like to be someone else.