It Came From The Attic

Daniel Blackball, co-founder of the recently-closed Dunedin label/studio/DIY venue The Attic, reminisces about a scene that didn't give two shits about the 'new Dunedin Sound', let alone whether it was part of it.

Daniel Blackball, co-founder of the recently-closed Dunedin label/studio/DIY venue The Attic, reminisces about a scene that didn't give two shits about the 'new Dunedin Sound', let alone whether it was part of it.

Some nights, long after business hours, you might have heard music ricocheting through an alleyway on George Street, Dunedin’s main drag. More often than not, this was coming from the 70s-themed club hidden down the back, with its light-up dance floor and its 21st-birthday playlist on repeat (this would later become Dunedin's "most authentic" Mexican restaurant, playlist and dancefloor inexplicably intact).

What you were actually looking for was an unassuming entrance nestled between an optometrist and a confectionery store, the golden numerals 140 recessed into the pavement. If you were lucky, and we were prepared, there may have been a triangular logo scrawled on the pavement in chalk, assuring you that you were headed in the right direction.

We were not that prepared on the night before Christmas Eve, 2011. For the two police officers making their way up the three aggressively-lit flights of stairs, though, the cluster of people smoking on the otherwise-desolate street had been a pretty good giveaway.

Up those stairs was a small, dirty-white lobby, with a rundown toilet and kitchen to the right (don't open the fridge). The lobby led to a long gallery space with holes in the floorboards and a handleless door at the end. The officers were greeted in that lobby by a smattering of now-nervous door people, and politely escorted through the empty gallery to the handleless door.

That door could have easily opened into a storage closet, but for seven years it was the entrance to The Attic. A large, dusty room in the centre of the city, The Attic was the centrepiece of this late-19th century building, with high, exposed A-frame beams and a long-closed elevator shaft above. Discarded lengths of wood and corrugated iron were piled up in the corners of this space: an art space, recording studio, record label and sometimes-venue.

The officers entered this room in December 2011 to find around 80 people, with their bottles of cider and ten-dollar wine, sitting huddled in a half-circle. In the middle of the crowd, perched on two rickety chairs and lit by two anglepoise lamps, were Freddy Fudd Pucker. Armed with only a guitar and an accordion, they were creating the most joyous racket, blasting it over the wind blowing through the cracked windows. This was the second-ever Attic show, the first having only happened a week earlier. Thanks in part to the mercy of the officers that evening, it was just the beginning.

It’s easy to fall into the familiar romantic traps when talking about Dunedin and its music scene. We can talk about the influence of the city – its isolation, its gothic architecture, its dampness – and we can talk about that sad boy "sound". None of these things are strictly untrue, but I don’t think they have the same bearing on the music and art that people are making in Dunedin anymore, not like they once did. We have the internet now. We consume the same media as everyone else. We just have to wear a few more layers.

What we do have is space, both figuratively and literally. While the cost of living is significantly higher now, in 2011 it wasn’t impossible to survive on a part-time job, pay the rent, and still be able to find yourself a dingy studio or practice space.

Dunedin is also, and will always be, a student town. That makes it a transient town, at least until the city can work out how to retain anyone over the age of 23. The music scene waxes and wanes every few years; there’ll be a spike for a while and the scene will pop with activity (and the attention that goes with it) before slipping back into a quiet slumber.

2011 was one of these transitional years. The stalwarts of Dunedin music in the previous years – Thundercub, Tono and the Finance Company, The Biff Merchants, TFF, Mr. Biscuits et al. – had either moved on or disbanded. The scene was in a process of regrouping and refocusing. The number of venues for new bands was also dwindling. If you were a Dunedin band just starting out, the only venues that were readily accessible to you were Refuel at University of Otago and, if you were brave, The Crown Hotel on Rattray Street.

I met Freddy Fudd Pucker, real names Tom Young and Sarah Gautier, in June 2011, six months before their Christmas Eve show. I’d invited them to be a part of a music documentary series I’d been chipping away at in which Dunedin bands would record a live session in a peculiar location. Because they were only in town a few days, it was up to me to find that location. Thankfully, a few weeks prior to filming Tom Garden had invited me to move into a studio space with him and Lee Nicolson, Oli Bridgeman, Sam Caldwell and George Driver. Having not seen it, only knowing the ludicrously cheap price, I immediately said yes. It was probably the most important uninformed decision I’ve made in Dunedin.

The recording session took place on a blistering cold Sunday evening in June. Tom Young had been rummaging through the trash that populated the front room and discovered a battered suitcase to act as a drum. The small crew of five and a few studio residents stood in silence while the suitcase, along with a guitar and accordion, reverberated throughout this untouched and unloved attic.

Lee Nicolson is an excellent musician and guitarist, one third of Thundercub, the mastermind behind the Attic-born band Space Bats, Attack!, able to bend sound to his will with his self-constructed, self-engineered guitar pedals. His genius led the way, helping us find what the space could be. That genius was complemented by his generosity. His willingness to fix broken gear, give advice or lend a helping hand with recording is what took The Attic from a few guys holding the odd gig to something ultimately entwined with the local music scene. That started in the middle of 2012, when Lee offered to produce albums for two high-school bands: the short-lived, breakneck punk-pop band Ostrander Aardvark, and a two-piece which would quickly become a staple at The Attic and in the wider Dunedin music scene, Astro Children.

I first saw Astro Children when they were leaving high school. They were part of a youth mentorship project called 'The Chick's Project', in which high-school bands would be paired with established local musicians and would take part in a series of shows and workshops at Chick’s Hotel. The project was run by Lee's partner Jess Young: other participants included Ostrander Aardvark, Kane Strang, and Josh Nicholls, then a member of the band A Distant City and later Space Bats, Attack! While Astro Children were impressive, it wasn't until a few months later, when I saw them perform again at a Battle of the Bands, that I realised they were working on a level far beyond most bands I had seen in the city.

Isaac Hickey held the fort behind the drums with a forceful kinetic beat; Millie Lovelock paced the stage, her face not giving anything away, and threw her whole body without warning into a trance-like sway. She’d howl into the mic, reverb spilling from her amp. They only had a couple of shows under their belt but this was a declaration. They simply did not give a shit about the sea of indie rock covers bands that they were sharing the stage with. In my mind, there was no doubt who should open for Tono and the Finance Company's all-ages gig at The Attic a few weeks later.

The recording sessions all took place late in the evening so we wouldn’t disturb anyone else in the building. Lee, always the improviser, had assembled a rag-tag collection of recording gear in the corner of the room, lit only by a few stray lamps and the glaring light of an iMac. Between takes, Millie and Isaac huddled up against a glowing bar heater, struggling to fight off the cold, while Lee fastidiously adjusted mic positions and recording levels, trying to capture the energy that they radiated on stage.

Only a few weeks after that recording session, a group of of us sat around in a circle in that large, dusty room assembling, stamping and hand-numbering Astro Children's first EP, Lick My Spaceship. It was becoming clear to us that The Attic should be a place where we produced things that otherwise wouldn’t exist. After all, we had the space, the knowledge and the manpower. If we really wanted to, everything, from practicing and recording to production and release shows, could be done within the same four walls.

Lee organised a lot of sessions, and keeping track of what everyone was doing was proving difficult. Oli and George teamed up with Louis Smith (The Gideons and The Maybe Pile) and Paul Cathro (Ha, The Unclear and Alizarin Lizard) to form Fat Children. Chris 'Bugs' Miller and PMK had moved into a room adjacent to the main space and were methodically working on their hypnotising project, The Entire Alphabet. Adrian Ng had moved into The Attic to start on the newest iteration of a project he had been working on since high school, Trick Mammoth.

The first digital compilation release, It Came From The Attic, set our plans to turn The Attic into some form of ‘label’ in motion. Released with assistance from Muzai Records (whom we’d become internet friends with) and Under The Radar, It Came From The Attic was the New Zealand music community’s introduction to many of these artists. I can’t help but single out the follow-up compilation, It Came From The Attic – The B-Sides, as the catalogue’s overlooked gem: a compilation of scrappy demos, experiments and live tracks released in a run of 25 CD-Rs, each housed in a numbered white sleeve and finished off with a red Attic stamp. I hand-carved the stamp myself. It would go on to be the door stamp for our gigs and it still sits on my desk today.

Every track on The B-Sides is a strange beast. Space Bats, Fat Children, George Driver and Trick Mammoth showed their working with punchy demos and outtakes. The space itself was centre-stage in a live-in-the-Attic recording by Brown (later renamed Ha, The Unclear), a late-night collaboration between Adrian and Lee, and an acoustic Astro Children track that Adrian recorded in the stairwell with a Singstar mic and a cardboard box. It was messy and disjointed; I don't think anyone was rushing to claim this was the ‘new Dunedin Sound’. But the playfulness and immediacy of the recordings represent best the energy of what I experienced during those years.

Digital releases like It Came From The Attic and The B-Sides were our bread and butter, the most efficient way to keep on top of our output. But an unexpected TradeMe listing by local engineer Tex Houston meant we got our hands on a hefty cassette duplicator, which we fondly nicknamed ‘The Replicant 3000'. It let us get our hands dirty with a handful of limited cassette releases: a live Anthonie Tonnon album, Adrian Ng's haunting side-project Mavis Gary, Dinosaur Sanctuary (a group consisting of Kane Strang, Astro Children's Isaac Hickey and Ostrander Aardvark’s Josh Hunter), and an album called These Walls Will Shout from Wellington's The Shocking and Stunning, consisting of live tracks from two of their Attic shows recorded by Lee.

The Replicant 3000 wasn't as reliable as its name would've suggested: the cassette production process usually involved me painfully hand-dubbing each cassette. But we did it in-house, along with creating the artwork and assembling the packaging. Everything that could be was done within our four walls.

We capped off this period of the Attic in 2014 with our Singles Club project, a series of monthly(ish) A- and B-side releases by Dunedin artists. Recorded and produced primarily by Adrian Ng, with artwork by myself, the project let us open our doors to a wider group of artists, occupying every corner of The Attic.

Speaking to Adrian's understated trolling, he assigned each B-side. Lucy Hunter (Opposite Sex) would be crouched over on the gallery floor and howling into a mic one month, and darkwave pop duo Strange Harvest would be grappling with an Earl Sweatshirt cover the next. Each artist occupied the space differently. Some opted for a more traditional set-up in the main recording space. Others, like Anthonie Tonnon and Shenandoah Davis, picked out an overlooked corner of one of the many other rooms.

The privilege of being present during these smaller, intimate moments, and the opportunity to get them out into the world, will always be what sticks with me. For a lot of other people, it will be the seven years of live shows that mean the most. For a space that technically wasn't allowed to be a venue, we managed to get a lot across the line.

Each show made the room its own, configuring the space differently, but the vibrant coloured lights and drunken swagger were a constant. We produced a heaving dancefloor for bands like BnP, Thundercub, Miss June and The Beths (for their first Dunedin show), and we provided a space for some of the last shows ever by Street Chant and God Bows To Math. The Shocking and Stunning played a hypnotic set, engulfed by smoke from a smoke machine and lit by a single red lamp. Lucy Hunter would somehow get a piano up four flights of stairs and still deliver a breathtakingly raw performance to a crowd sitting in piercing silence. And I couldn’t forget any of the performances from the bands that called The Attic their second home. It felt like a homecoming every time Space Bats, Attack! or Astro Children took to the makeshift stage, filling every crack in the building with noise and whipping the crowd into a frenzy.

Seven years is a long time for most things. We certainly never considered that The Attic would grow big enough to stick around that long, and I wouldn’t be offended if people assumed it had closed much earlier. Its later life, from 2015 to 2018, was less public-facing, due to restrictions put in place by the landlord, but that’s not to say it wasn’t productive. Josh Nichols (now of Koizilla as well as Space Bats, Attack!) and musician and engineer Nick Graham became Attic stalwarts as many original residents moved on to new things and places. A new generation of bands – Koizilla, Mary Berry, The Rothmans – stepped up and took over the responsibility of filling those four walls with as much noise and as many people as they could muster, all against a backdrop four floors down of drunk students marching towards The Octagon. And Lee and I acted as custodians, ensuring that the place didn’t burn down and that all the bills were paid.

I make my way up those same four flights of stairs on a cold Tuesday evening in September 2018, as I have done countless times over the last seven years. The entrance and gallery space are empty, but there’s muffled chatter from beyond the handleless door. Behind that door, around 30 people are huddled together in the middle of a cavernous room. While a long way from the number of people those two officers walked in on back in 2011, the room is buzzing with the same quiet excitement and anticipation. I join a group of friends near the stage, conserving heat under shared jackets and blankets. I don’t really know the rest of the audience, many of whom look like they were barely in high school in 2011.

Reverb fills the room; a persistent low hum from the amp. Millie Lovelock paces between the amp and her recently upgraded pedal and vocal-loop set-up. This is her last Repulsive Woman set before she flys off to Berlin for the Red Bull Music Academy. With Repulsive Woman, Millie has traded in Astro Children's abrasiveness for haunting, beautifully-layered vocals and hooks for miles. She lights up the room. She’s one of the best frontmen this town will see.

Astro Children are due to take the stage later, but it’s a Tuesday night, unbelievably cold, and I am not 23 anymore. I reluctantly slip out a few songs into Mary Berry's excellent set. The icy-cold wind and rain lashes my back as I make my way home. I fumble with my phone and message Millie, to apologise for being a bad friend.

Leaving feels weird. At first I feel guilty about leaving – this would one of the last times I saw Millie before she headed off. But that’s not the reason this feels weird. We’re close friends, even if our relationship mostly plays out in daily Messenger conversations. It’s not until later in the night that it occurs to me that it felt weird because it felt like the end. At least for me. A few days later, Millie tells me that she felt the same way.

A few months later, just before Christmas, Lee and I are up in that dusty room late at night, drinking room-temperature beer. Surrounded by broken drumsticks, rubbish and seven years of leftover debris, it still feels weird, but it also feels OK. I still don’t really know what The Attic was, but I’m thankful it was something.

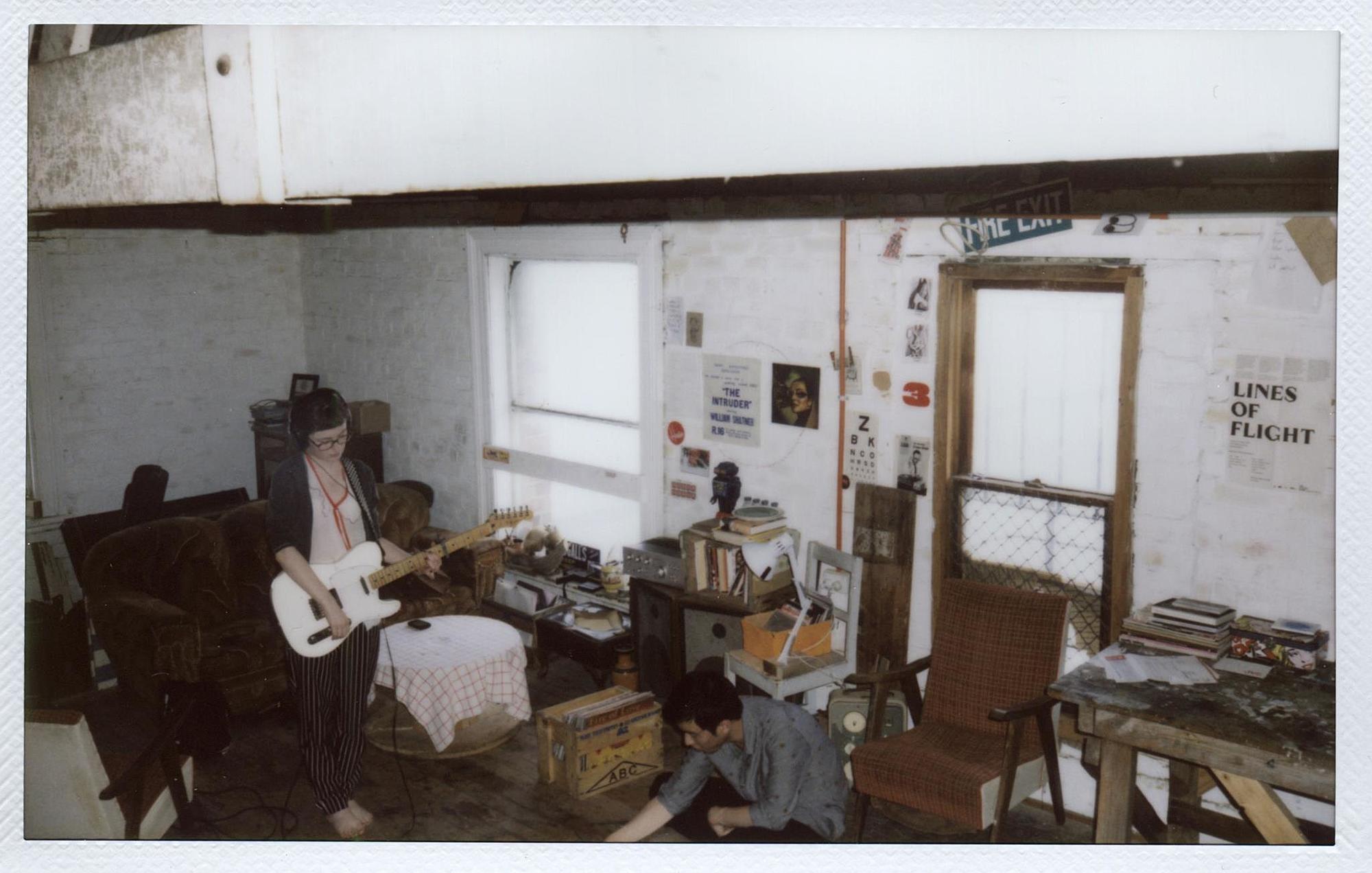

Header image: Repulsive Woman live at The Attic. Image credit: Fraser Thompson/dunedinsound.com.