Why I Am Not a Feminist: A Conversation with Jessa Crispin

Sarah Jane Barnett talks to American writer and critic Jessa Crispin about her new book, Why I Am Not a Feminist.

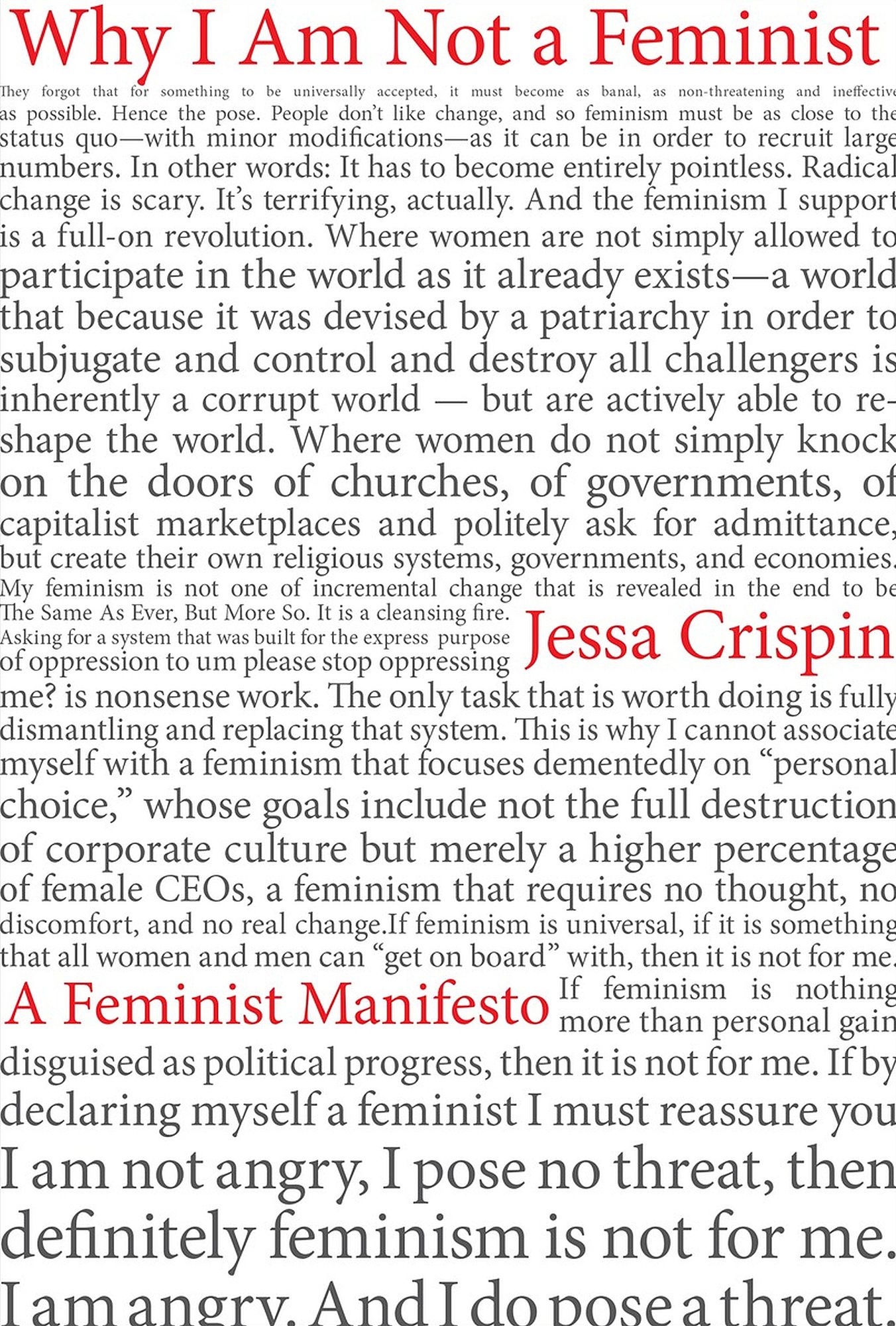

Jessa Crispin's new book Why I Am Not a Feminist: A Feminist Manifesto has been called a ‘searing rejection of contemporary feminism.’ With such a title it was always going to create controversy. The American author and critic - she founded the popular book blog Bookslut, which ran from 2002 to 2016, and the literary journal Spolia - has never minced words: in one interview she expressed her disinterest in American literature and her dislike of MFA culture.

Why I Am Not a Feminist is Crispin’s third book (The Dead Ladies Project and The Creative Tarot came before). It has had mixed reviews: most have praised Crispin's 'sharp' mind and 'gutsy' approach, but reviewers have also noted that her ideas need expansion; she does not, in essence, provide answers.

This week, Crispin will be speaking with Jo Randerson in Wellington about her new book. Books Editor Sarah Jane Barnett caught up with Crispin to ask her about liberation, alternative structures, and men's oppression.

Sarah Jane Barnett: Can you tell me about growing up and whether feminism was part of your childhood? When did you first say to yourself, ‘I’m a feminist’?

Jessa Crispin: I was trying to pin down the time when I started to really understand what feminism was. I think it must have been in my early 20s. I grew up in a very conservative town, in a very conservative family, and so my only real political consciousness at the time was 'not this.' I had my Sunday school teacher telling me homosexuality was a sin and abortion was murder and on and on, and I had a kind of instinctive feeling that all of this God-based morality was wrong.

It wasn't until I left Kansas and started working at Planned Parenthood that I understood what feminism meant. That it wasn't just a kind of propping up of women, it was an ideology that offered a chance to remake the world. It was important, I think, that my intellectual introduction to feminism, basically just reading a whole library's worth of feminist material from biological gynaecology textbooks to the collected writings of Margaret Sanger to the radical thinkers of the Second Wave, coincided with hands-on work with women's rights. It was important for me to have an abstract and a concrete understanding of how this works.

The title Why I Am Not a Feminist seems purposefully inflammatory – most feminists (myself included) can’t walk away from a woman who makes that statement. Are you trying to spur feminists into engaging with their own definitions of feminism? Do you think we’ve gotten too comfy, or as has been described elsewhere, we’ve had a ‘declawing’?

Jessa Crispin: I think the word has become so meaningless through the various people trying to use the word against us, and by that I mean pop stars using it to sell records, men using it to get laid, politicians using it to get elected, corporate executives using it to justify their own advancement, and so on, that we need to really think about what feminism means again. Not just to us personally, but for all women.

In a way, the book is merely tracking the way I came to feminism and came to think about feminism, how I built my own sense of feminism by thinking through the problems of rich women using the word or pro-lifers using the word or Taylor Swift using the word.

This eyeliner isn't just eyeliner, it's a reflection of your inner self...

One aspect of modern feminism that you critique is the ‘spoil yourself stupid’ trope where self-care is sold as the same thing as self determination. Or as The New Yorker argues, ‘The inside threat to feminism in 2017 is less a disavowal of radical ideas than an empty co-option of radical appearances – a superficial, market-based alignment that is more likely to make a woman feel good and righteous than lead her to the political action that feminism is meant to spur.’

This commodification of feminism – using the movement to sell magazines and spa days – made me think of the way yoga has been commodified by the West, or how diet culture has rebranded itself as the ‘clean eating’ movement. Tell me your thoughts on the interaction between the structures of capitalism and feminism.

Jessa Crispin: As more and more women enter the higher levels of the work force, they have more and more women. And the best way for a corporation to convince a woman to give them their money is to flatter them. So this eyeliner isn't just eyeliner, it's a reflection of your inner self, it's a tool of empowerment. It's this idea that you can buy your liberation or you can buy your political participation. You don't have to volunteer, you can just donate. You don't have to fight for women's rights if you're fighting for your own rights.

I think with self-care specifically, what is important is to remember that when you're using that term to justify getting a manicure at a spa, you're not taking care of you, someone else, probably an immigrant who is being paid minimum wage, is taking care of you. It's important to remember that it's easy to fall into the trap of exploiting underpaid labor in our quest for 'care,' and that in a lot of the cases, what we call care is just indulgence.

I often feel like my family’s choices reflect the choices I've given by society. I do most of my family’s housework, and for years I was our son’s primary caregiver. My husband works full-time, but I have to squash my career into a few days a week. Since having a child, my husband’s career has grown whereas mine has slowed, even though neither of us want this.

These experiences support your argument that women are fighting for equality in a system/structure that is inherently unequal; that what we need is liberation from the structure itself. The thing is, how can we simultaneously liberate ourselves while also surviving in the current structure? Where are the alternative structures?

Jessa Crispin: You are definitely right: there are few alternative structures for supporting women, particularly mothers. If we're not raising a child as a couple, there is little to no infrastructure that can help us do it. There is, in America at least, no subsidized childcare, the health care system is a joke, and so on. But it's not just the social welfare system that fails us. It's how we take care of each other. We have increasingly fractured communities and little sense of communal obligation, meaning you are emotionally responsible for the raising of your children, too. There's less of a sense of, your kid is everyone's kid, there's less of a sense of chipping in and helping out.

If you just look at something like, single people are more likely to die after a cancer diagnosis, all other factors being equal. That's not because single people having less healthy immune systems! It's because no one is consistently being their advocate. No one is there, checking to see if they passed out on the bathroom floor. No one, unless they can afford a private nurse, is there to make sure the medication regime is being followed.

We have allowed these levels of care to come only from the romantic partner, in the same way that health insurance in the US is more readily available through a well employed spouse, the way immigration applications are easier through a spouse, and so on. If you don't want to confine yourself to the tyranny of this idea of the couple, or if you are marginalized because of appearance, race, age, poverty, or any other reason, you're really on your own.

I dream of building these cities for women who want to live out of this heterosexual paradigm, like convents without the celibacy requirement. Where women (and men, why not) have a sense of obligation to one another, where they pick up each other's slack. Where they support one another, financially, sexually, emotionally.

I dream of building these cities for women who want to live out of this heterosexual paradigm, like convents without the celibacy requirement. Where women (and men, why not) have a sense of obligation to one another, where they pick up each other's slack. Where they support one another, financially, sexually, emotionally. Where everyone is a caregiver and everyone is being cared for, and not in the sense of the woman giving you a manicure. But I am a vulnerable, marginalized single woman, so I don't have the money to build them.

Let’s talk about men. Dismantling the structures of oppression for women must also involve dismantling the structures of oppression for men; I know men who feel little choice about their gender role. For instance, men are often not structurally supported to be stay-at-home Dads, or feel pressure to be the family ‘bread-winner’ or, most strikingly during the 20th century, to go to war.

Jessa Crispin: Yes, I agree that men are absolutely oppressed by the patriarchy as well. They're in a slightly trickier position, though, because they are essentially being asked to give up their power. It's one thing for a disempowered group to fight for power. It's satisfying, it's something they want. But to ask a powerful group to relinquish power? How does one do that? Particularly when, because of the economic crisis and so on, men might not understand the power they wield.

I think there has to be some sort of understanding with men of how they exist in the patriarchy. It's not like women just figured it out all on their own one day. It took writers like Mary Wollstonecraft and John Stuart Mill and so on to begin to look at it and examine it. I think that process has to begin again in the intellectual realm, and so far, I don't see it happening in a really powerful way.

Then there has to be a kind of development of androgyny in men. We women have been developing our masculine sides for a hundred years now. But I don't see it as a movement happening among men. Sure, there are individuals, but even feminism and the queer scene did not seem to have much of an effect on men's view of themselves.

They have my sympathy. It's hard work, what they're going to have to do. And I do think it's vitally important work. At some point, I hope soon, I do think it's reach a critical mass, but if you look at the side effects of this loss of power – mass shootings, terrorism, sexual assault, and so on – you can see both how much work there is to do and also how reluctant the majority of men are to do this work.

Jessa Crispin is presented by Pirate & Queen. She talks with Jo Randerson about her new book, Why I Am Not A Feminist on Thursday 9 March, 8pm at San Fran, Wellington. On Friday 10 March, she gives a limited capacity workshop on The Creative Tarot, 6pm at Double Denim HQ, Wellington. Full details and where to buy tickets at pirateandqueen.co.nz.