LB is Making Hip-Hop for the Suburbs

Han Li on how Sāmoan hip-hop artist and Elam School of Fine Arts graduate Albert Folasa-Sua – aka LB – found his voice and learned to embrace obscurity.

For a truly multisensory experience, listen to LB on Spotify while reading.

Albert Folasa-Sua just wanted to get some good grades. A graduate of the Elam School of Fine Arts at the University of Auckland, he had been surrounded by the avant-garde work of his peers for years. He reminisces, "One time we had a pool party in Albert Park fountain and we got 97 percent for it. It was for a sculpture paper." In this environment where weird stuff gets good grades, rapping didn't seem like a weird thing to do. So he did it and it went better than expected: "One of my tutors was like 'Yo, you're real good' and I was like 'Oh really, you think I'm good? I'll keep doing it' and it snowballed."

Hip-hop and the fine arts are not often seen as companions. While most of his peers at Elam loved his raps, he was challenged by tutors to back up his work with theory. "It was polarising," he says. "I had tutors telling me they loved my work and tutors telling me they hated my work." To him, though, rapping was a natural fit to what he was learning at art school. He saw parallels between sampling and concepts like appropriation, and found ways to present his music through installations. He started making spaces, and describes an exhibition where he set up a couch, coffee table and rug in the gallery and played his mixtape. "I played with the aspect of home and tried to make the viewer comfortable, because if they sat down they would probably have to listen to the music too. I was interested in domesticating an art gallery."

Stress and Progress is an expansive collection of tracks about family, tertiary education and acceptance of self

Grades are no longer the priority, but Albert – aka LB – is still making music that sounds like home. His recently released second project, Stress and Progress, is an expansive and warm collection of tracks about family, tertiary education and acceptance of self. Produced by his friends Nahsafe and Akshay Raju, its sample-heavy sound is laid back, like a lazy weekend strolling around suburban Tāmaki Makaurau. On standout opener ‘Home Sweet Home’ he offers a paean to the gritty neighbourhoods he grew up in, proclaiming "AKL is where I'm from" before asking "Where you from toko?1 / Where you from lah?”2 The questions are as good a distillation of the open-minded curiosity of multicultural Tāmaki Makaurau as I've heard anywhere.

Albert's vocals throughout the record are a particular strength. He first started rapping in the hotbox, eagerly joining in when his friends were freestyling. "All I really wanted to do when I started was to be as good as the guys in the hotbox," he remembers. These origins can be heard in his vocal style. High-pitched and playful, his voice has a looseness to it that recalls shit-talking sessions with mates. During songs, he often varies his pitch and syllable lengths in surprising ways. Yet it would be simplistic to only hear him through the casualness of his voice. His music – always grounded in the reality of his lived experience – is deeper than that.

Albert's family immigrated from Sāmoa to the North Shore in the 1980s, moving for work like many other Polynesian families. On the predominantly Pākehā North Shore, his family found a Sāmoan community in the western suburbs of Bayview and Birkenhead. Raised by his nana and mum, he had a traditionally Sāmoan upbringing, and tries to represent this in his bilingual rapping. "It is a blessing that I can rap in Sāmoan," he says. "Even though I might not be that great at speaking, I'm still going to spit what I do know. It's very important to me to stand firm in that."

Listening to Cole with the Rap Genius annotations, he became obsessed with the layers of meaning that could be packed into one line

Photo: Lemonwood Photography

Albert was "super insecure" as a child. "I was a chubby, fat little nerd and I was a pushover," he remembers. He came from a family of rugby players and would get compared to his athletically talented cousins, who used to make representative squads. His uncle would ask him when he would make the First XV. He laughs, "In my head I was like, I am never making that." His own interests diverged from the norms of his family. He would spend a lot of his time as a kid by himself, browsing through NBA stats on Wikipedia or playing Tekken on his Playstation 2.

It was one of these browsing sessions that got him into hip-hop. A friend told him to check out a then up-and-coming J Cole. Looking him up online, he came across the lyric annotation site Rap Genius (now called Genius). Listening to Cole with the Rap Genius annotations in front of him, he became obsessed with the layers of meaning that could be packed into one line. "That was the spark," he remembers. "It blew my mind. After I listened to that song, I went to find another song, and then a whole mixtape."

He started to make art his thing during high school. There, he would often draw Sāmoan tatau designs in the back of his textbooks while bored in class. In his senior years, he chose to take art subjects and was encouraged by his teachers to apply for Elam. "I had no clue what Elam was," he remembers.

His grad project was also his first mixtape. He named it dntBOTZit.KHAN, using Sāmoan slang

For a kid from a family without any university graduates, the sheer range of people and privilege on display at Elam was eye-opening. He found belonging in places like the Tuākana room, a space for Māori and Pacific students where he could walk in and expect to see a Brown face. Despite having to repeat his second year (he was held back after failing an "irrelevant" paper) he ended up excelling and graduated with first-class honours.

He remembers his time at Elam as important in building his practice. Being surrounded by so much weird artwork gave him the freedom to be as obscure as possible. His grad project was also his first mixtape. He named it dntBOTZit.KHAN, using Sāmoan slang that he knew people might not understand. "I didn't care," he explains. "I was making music for me and people who actually understood." Like his own Rap Genius-fuelled obsessions as a kid, he wanted people who didn't understand to "listen and be intrigued by what it meant."

This confidence to be obscure and embrace who he is can be heard in the hyper-specific references and audio ephemera layered throughout Stress and Progress. The brash ‘11:59’ starts with a sample from a Mortal Kombat minigame and finishes with LB comparing himself to a dizzying array of figures from Sāmoan and New Zealand pop culture – he's the first rapper I've ever heard mention Auckland Blues legends Carlos Spencer and Joe Rokocoko in a song, let alone rhyme them. On the sparkling ‘Mission’, he spends the second verse doing a roll call of street names of his childhood suburbs of Bayview and Beach Haven, taking us on a journey through places that aren't often glamourised in pop culture.

Other songs are about more common experiences. On ‘Bachelor’ he talks about his journey through university. Over a laid-back beat, the track first seems like an ode to being a bachelor until the second verse, where he rips into our broken university system: "I put in work six sefulu māsina [sixty months] to get my piece of paper / But my student loan, and debt up to my neck that's the chaser," he raps, articulating thoughts probably shared by many in his generation.

That student loan is still around his neck today. Before our call, Albert has just finished a shift at the AS Colour warehouse, a company he has worked for since university. He recently stepped down from his role as retail manager so he can choose which days he has off to work on his music. His dream is to be an artist full time. "I'm intrigued by what I could create," he says. "I didn't ever expect to be a rapper. When I went into art school, the whole idea was money-based. I wanted to be a wedding photographer or a cruise photographer. Because I would either get a free cruise, or free food."

**

Han Li: You were born in New Zealand but had a pretty traditional Sāmoan upbringing. How do your two different cultures interact with each other?

Albert Folasa-Sua: I think I always perceive myself as a Sāmoan first, before I bring on the New Zealand side of me, even though I might not be fluent [in Sāmoan]. I think it's because of my home. My nana and mum talk to me in Sāmoan. My home environment is a very Sāmoan environment. They would call it faʻa Sāmoa, the Sāmoan way of life. You can hear pieces of my Sāmoan influence in the things I say. I think it’s very important to me to stand firm in that, in the little things that I know. To still represent and put a flag in the ground for my heritage.

HL:What was Elam like?

AFS: I think it chucked me into the deep end in terms of art. I had tunnel vision on what art was supposed to be, once I got to Elam it was kinda like "bang". My first day we watched Marina Abramović, the contemporary performance artist. I was like "Eh??" That was a big shock. It was a challenge.

You would meet people who were already in the art scene and felt so comfortable. I had to find my way and see where I was comfortable

Photo: Darryl Chin

HL: How was the environment, coming into a place like Elam after your kind of upbringing?

AFS: It was also a big shock. The people, the range of people and the types of people, I don't think I was ready for. Maybe that was me being naive. You would meet people who were already in the art scene and felt so comfortable. I had to find my way and see where I was comfortable. There was definitely an elitist feel to it. If you made a certain type of work, the ego would inflate and you would put yourself above your peers.

HL: What kind of work do you mean?

AFS: To be honest the work wasn't that great, it was the privilege that came with it. The fact that they would come into art school having already read a lot of stuff because their families could provide that kind of education. They could walk in and be like, I already know this. You should listen to me.

HL: You mentioned that Elam was not Brown, did you ever think it was racist?

AFS: Yeah. I think, in turn, I also believed the university was racist and I think Elam was just an extension of that. There were times I felt my peers were mistreated, they were treated as a number because they were seen only as a paycheck to the University. There was a disconnect of understanding the problems that we faced in our culture, or even just mental health in general. One of my close friends, he begged and pleaded with them to continue his practice but they didn't let him, because there was one paper that they didn't let slide. There were problems that [the university] didn't want to face because if they faced one, they would have to face all the other cases.

People who I would hang out with would smoke weed in the hotbox and they would start rapping and that was the cypher

HL: How did you first get into rapping?

AFS: I only really started because during university, halfway through my first year, I started smoking weed [laughs]. People who I would hang out with would smoke weed in the hotbox and they would start rapping and that was the cypher. And I was like "Yo, let me try this" and that's kind of where the seed started. I was always into hip-hop but I never had the thought to rap. But I was always ingrained in it, like it would be cool if I could string eight bars together. That was happening on one side, art school was happening on the other side, and I thought why not put them together.

HL: What was the process of you getting into music more seriously?

AFS: I had barebones skills, so I had no audio equipment, no recording equipment. [When I first tried to get recorded] a lot of the time I just had to ask mates. Then I found a mate studying at the School of Audio Engineering and we made a band called Keith. My friend Akshay, who mixed Stress and Progress, played a big part in it. With Keith there was a collective called Lowtide on K Road, they had a space where they would play open-mic nights. My first big challenge as a rapper was when they asked me, “Do you think you could just freestyle for an hour?” I told them yes, but at the time I was thinking "I don't know G." I was scared as hell. But it definitely helped make me comfortable. We played open mics for a year and that's where I learnt to perform, essentially.

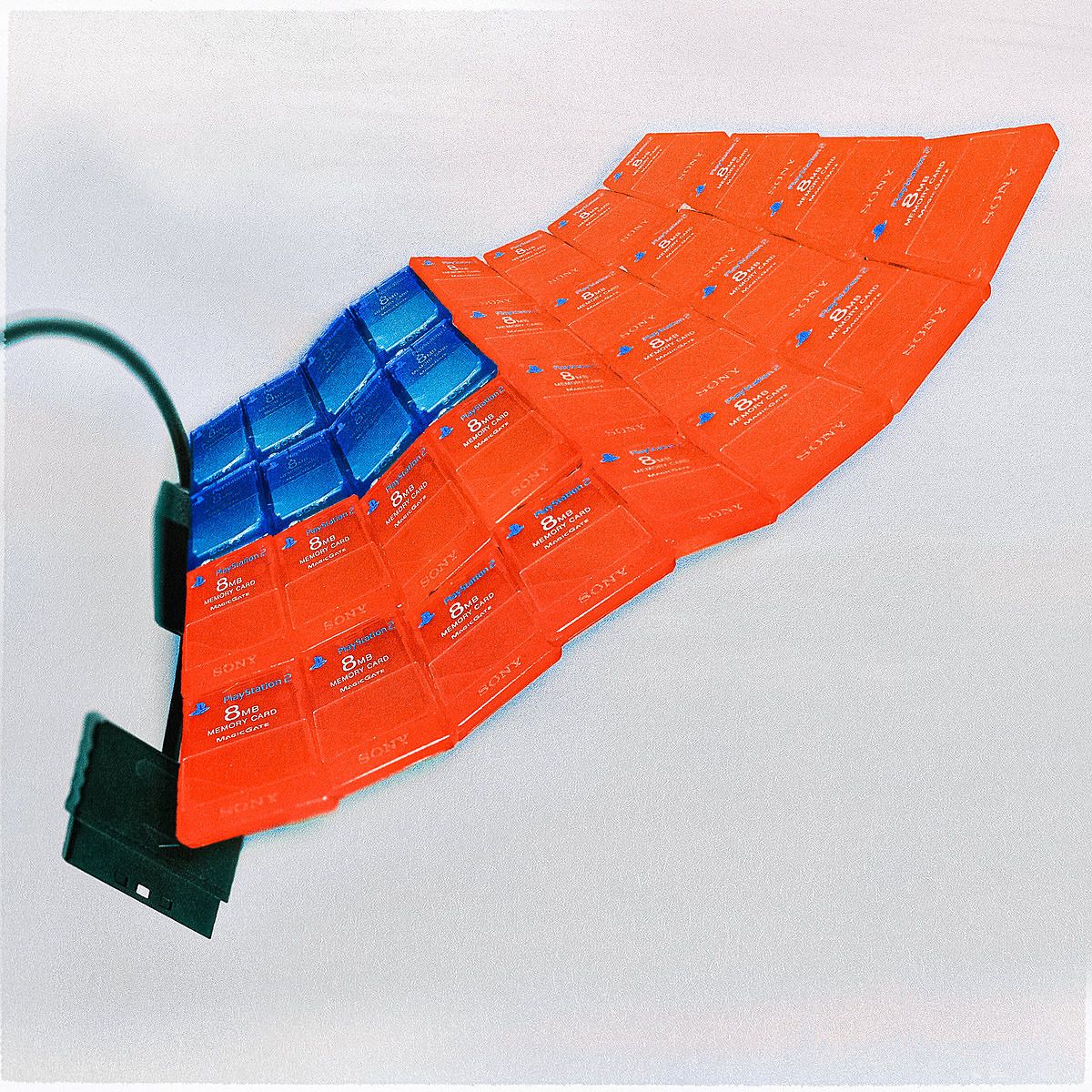

Stress and Progress album cover

HL: I found all the video-game sounds in the project intriguing. I think I heard commentary from Rugby 08?

AFS: Yeah definitely. I've still got my PS2. On the cover [of Stress and Progress], those are my real memory cards. I don't have that many, but I gave them to the graphic designer [Bryson Naik] and was like, "Can you make the flag out of it?" But the sounds, I don't know, I think I just loved the PS2. It was the sound of my childhood and it was super nerdy. There are Easter eggs in there. If you played the games you know what it is.

1 Tongan slang for bro, short for tokoua which means brother.

2 Niuean slang for bro, short for laho which means dick.

Stress and Progress is available for purchase on Bandcamp.