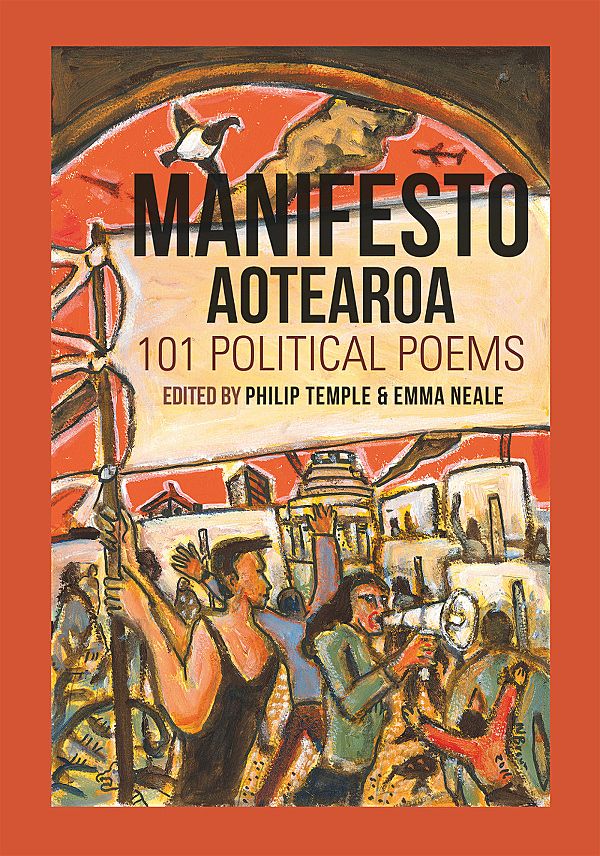

Two cheers for democracy: A review of Manifesto Aotearoa

Tim Upperton spends time with Manifesto Aotearoa: 101 political poems and decides that editors Neale and Temple have done a fine job.

Tim Upperton spends time with Manifesto Aotearoa: 101 political poems and decides that editors Neale and Temple have done a fine job.

One hundred and one political poems, by nearly one hundred and one poets – who knew we had so many? Yet it’s odd, in an anthology as generous and inclusive as this, how you notice who’s missing. It’s a shame that outstanding political poetry from the past is outside the ambit of this book – the broadsides of Whim-Wham, Glover, Baxter, Fairburn and Frame would have provided a rich historical context for this contemporary offering.

Co-editor Philip Temple rightly points out that there’s another anthology-in-waiting here. I particularly missed Bill Manhire’s ‘Hotel Emergencies,’ and among other practising poets, I also missed Helen Lehndorf, Jenny Bornholdt, Ashleigh Young, Hinemoana Baker, Stefanie Lash, Bob Orr, Tim Jones, Sarah Jane Barnett, Sam Hunt, Helen Heath, and Apirana Taylor (there’s an excerpt from Taylor’s ‘Sad joke on a marae’ in Temple’s introduction). But this is an invitation-to-submit volume rather than a survey of what’s already out there in books, magazines and online, so maybe some poets simply missed the memo. (I missed the memo.) And maybe some poets just don’t have a political poem in them. But maybe every poem is political. And if that’s too woolly and undefined, then what is a political poem, exactly?

Fellow editor Emma Neale doesn’t address this directly; instead she points out the affinities between the poet and the politician – ‘both need to be sweet-talkers’ – but also how, in every other way, they are diametrically opposed. It’s hard to disagree, but what can sweet-talking poets achieve politically when politicians have the power, and poetry, in Auden’s words, ‘makes nothing happen’? When Shelley wrote that ‘poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world,’ the emphasis, for me, falls on ‘unacknowledged.’ If poetry has any power at all, and I’m not sure it does, it’s subterranean and slow; it doesn’t move at the pace of election cycles. As Neale says, ‘the language of poetry is a stage in deeper consideration, reassessment, taking the long view.’

Philip Temple’s claims for political poetry are less tempered than Neale’s: he says ‘political poems are the most open and cogent expression of democracy, the most vivid and eloquent calls for empathy, for action and revolution, even for a simple calling to account.’ OK, but what in this working definition distinguishes political poems from other kinds of arguably much more effective political writing – from, say, a book by Nicky Hager? This is definition by superlative: political poems are the most open and cogent expression, the most vivid and eloquent call. It’s a bit like Coleridge saying that prose is words in their best order, and poetry the best words in their best order. As manifestos go, this book is bold and declarative: it may not have the flavour of a particular political party, but it’s firmly to the left of centre (no Rudyard Kiplings or Ezra Pounds here).

Manifesto Aotearoa is a call to – not arms, exactly, but arm-waving.

Manifesto Aotearoa is a call to – not arms, exactly, but arm-waving, captured in the wonderful, action-filled cover-art by Nigel Brown: people are running, protesting, standard-bearing, and loud-hailing; planes and smoke fill the sky. The Beehive squats in the centre, rather menacingly, like a Dalek bent on extermination. A kererū soars improbably above it all. I immediately liked this book for its dynamism, its stridency, its giving a flying fuck about what’s happening to this country. Poetry on the page, in New Zealand at least, seldom raises its voice, so when it does, you prick up your ears and listen.

But the strident, raised voice of many of the poems here also bothered me. It reminded me of a protest march I went on in long-ago 1986, against the so-called Cavaliers rebel tour of South Africa. We marched around the Square in Palmerston North, a ragged band, with a gaunt, pale guy at the front holding a megaphone and shouting “Amandla!” at odd intervals, and “Remember Soweto!” My fellow-marchers would echo faintly, dutifully, “Remember Soweto!” I felt stupid and angry, hating the shouty guy but believing in the protest. I don’t like crowds or shouting much, so maybe it wasn’t the best place for me. Perhaps that’s why I’m usually attracted to poetry of a quiet, reflective, indirect mode. In my ear I hear Emily Dickinson whisper, ‘Tell all the truth, but tell it slant.’ I hear Jenny Bornholdt, in her introduction to Best New Zealand Poems 2016: Poetry is ‘mostly best when poets don’t “say the thing”... The poem is the thing and you have to trust that it will be so.’

And isn’t ‘scamps’ a trivialising of the damage these politicians have done? Like calling Donald Trump a rascal.

The first part of this anthology is called ‘Politics,’ which seems kind of redundant, but what distinguishes these poems from those in the sections that come after is that they confront the political scene and named political figures directly. In this section the satire is broad, and poets are most in danger of ‘saying the thing’, sometimes with a musty diction, as in Kevin Ireland’s ‘A song for happy voters’: ‘Those who voted for these scamps / have earned their blessed sleep.’ (And isn’t ‘scamps’ a trivialising of the damage these politicians have done? Like calling Donald Trump a rascal.)

That topical issues and specific politicians are often the targets of scorn gives some of these poems an already expired currency: the flag debate, for example, is now an absurd memory, and the retired Prime Minister John Key also (his recently conferred knighthood merely compounds the absurdity). The best poems here rise above such particulars, as in Richard Reeve’s satire on the vacuous, indiscriminate culture-vulturing of the boomer generation, ‘Boom’: ‘On the topic of culture, they refer to the Festival, / trans-Atlantic gurus, the impossible grinning conductor; / the hip hop acapella from Soweto they liked best of all.’ It’s the kind of skewering Baxter did so well. Or Maria McMillan’s ‘How they came to privatise the night,’ in which the neoliberal tendency to commodify everything as a resource to plunder extends to our sense of selfhood, privacy, identity: the darkness that is assigned an economic value includes ‘Our dark selves / Small nights we carry with us.’

In Part Two, ‘Rights,’ the poetry focuses on economic disparity, the rights of workers, women, Māori, and the right to free speech; which is to say, this part is about power, and who wields it and who doesn’t. In Part Three, the focus shifts to ‘Environment’; in Part Four, ‘Conflict.’ These categories are of course a bit blurry: Jeffrey Paparoa Holman’s ‘Check Inspector 29,’ for example, which concerns the Pike River mine disaster, leads Part Two, but with its castigation of ‘politicians in their beds lying straight and true,’ it would fit just as easily in the first. It doesn’t matter. Indignation is the dominant tone: of course it is, as one poem after another basically denounces evil. You can’t help but cheer them on, as we all cheered Tony Walsh when he recited his poem, ‘This is the place,’ in the aftermath of the Manchester bombing. But saying the right thing doesn’t guarantee a good poem, and I’m not sure how many of these poems will outlive their particular moments.

Some that will: Airini Beautrais’s ‘No time like the 80s,’ which, in its breadth and resonance, recalls Auden’s condemnation of another ‘low, dishonest decade’ in his poem, ‘September 1, 1939’ (and thus also reminds us that history is cyclic rather than a record of progress); Tusiata Avia’s ‘I cannot write a poem about Gaza’ (in which the impossibility of writing atrocity becomes, through refusal, fury and despair, possibility); and Janis Freegard’s ‘Arohata,’ a description of a prison visit that manages to convey the bureaucratic horror, the uselessness, destructiveness, and indignity done to the human spirit that characterize the prison system.

The editors have done a fine job of bringing together a diverse range of poems and poets, and each time I’ve returned to the book I’ve found something new and good, often by a poet I’ve never heard of before. Two cheers for democracy! Which would’ve been a great title, if E.M. Forster hadn’t already claimed it. In that book, Forster notes that ‘I have found by experience that the arts act as an antidote against our present troubles, and also as a support for our common humanity.’ Yeah, they do.