Moments of Being: An Interview With Aorewa McLeod

When you're writing a novel about your life, how do you choose what's worth retelling? Rosabel Tan talks to Aorewa McLeod about her book, her brother, and the relationship between memory and fiction.

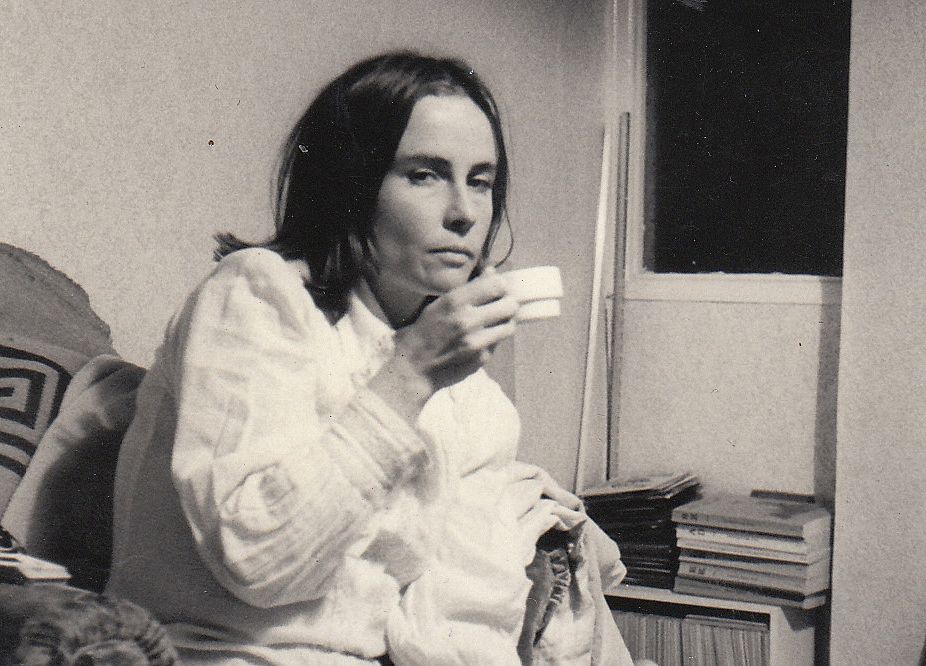

Aorewa McLeod is worried. It’s a week before her book launch and she’s sitting at the kitchen table in her Kingsland villa, a sprawling property bursting with books and paintings and a small peppy dog named Phyd. A plate of miniature pastries sits atop a pile of flyers – for The Auckland Pride Festival, for tiles (“We’re renovating”), for a local gallery (her partner is a painter). Her words: “I’m quite worried about the launching.”

“Because of the people in the book?”

“Particularly one or two.” She speaks unhurriedly, in a deadpan and faintly theatrical tone. “One who I was worried about I actually gave her the rough draft, and she read it and was okay, but my brother is the one I’m really worried about, because he’s come out a bit villainous.”

It’s true. He does. “So he knows you’ve written the book?”

She looks contemplative. “He knows I’ve written a book.”

“He doesn’t know that he’s in it?”

“No.” She doesn’t sound perturbed. “I gave it to my other brother – only one brother appears in the book, and he’s an amalgam of one brother and a made-up brother, and I gave it to the other brother to read and he quite enjoyed it.” She tilts her head up slightly. “But he’s not actually in it.”

And her brother, the one who’s in it – is he coming to the launch? “I’m not sure,” she says. “I suppose I have to invite him.”

Prefacing Who Was That Woman, Anyway?is a disclaimer:

All these events are inspired by real-life

events. Some details happened in real life,

some did not. The characters are fictionalised

and given fictional names.

“It’s funny,” she comments, “I just read Alice Munro’s latest collection of short stories and she says, ‘they’re autobiographical in feeling, if not entirely in fact.’ I should have said something like that.”

It’s this kind of insatiable longing – this gentle, magpie-like engagement with the world - that characterises her book. Written during her MA year at the International Institute of Modern Letters, Who Was That Woman is a series of loosely connected episodes offering candid reflections on what it was like growing up in New Zealand in the 1960s and beyond - as a lesbian, as an academic, and as a passive, resentful daughter caring for her mother. We follow the central character, Ngaio, through summers spent working at an ice cream factory and, later, at a psychiatric ward in Nelson, where her experiences are both a damning commentary on our early healthcare system and a disarming tale of sexual discovery. She moves to Oxford to study, but reluctantly returns when her mother has a stroke. She marries. Travels. Teaches. Drinks. It’s an incredible history, both personal and political, and like the writer herself, is frank, fierce and darkly funny.

I ask if she had considered rewriting the scene featuring her brother – the one she’s particularly worried about. “I did,” she says, “But I quite liked it, as fiction. It has to be like that. It just has to be. If you took him out it’d be a much duller chapter.” She quotes from Jeanette Winterson’s recent memoir, Why Be Happy When You Can Be Normal, which marks a stark return to the subject matter of her first novel, Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit: “She says: Dysfunctional families have a code of silence, and the one who breaks that silence is always going to be the villain. And I certainly have – the brother who has read it already, I gave it to him because I know he thinks our family was totally dysfunctional, whereas my other brother and my sister actually think the family was alright.” She sounds vaguely bemused.

*

She didn’t set out to write autobiographical fiction. “The reason I went to Wellington,” she explains, “was because I’d written a novel, which wasn’t me, which wasn’t autobiographical, although it was sort of lesbian-feminist-academic. It was the same world as I came from. And it had been rejected by all the publishers so I went down thinking, ‘They’ll teach me how to write a proper novel!’

Everybody in the class was asked to write a short piece about themselves, to share on the first day, and she wrote about being a student, at Oxford, in 1966. “And [my supervisor] Damien said, ‘This is great! This is real history! And it’s magnificently written history.’ Well of course, once he said that, I had to go on.”

The challenge with autobiographical fiction is that you’re rewriting your life and deciding which parts are worthy – what makes a good story – and which bits need padding. “Looking back on one’s life,” she says, “it would be fiction anyway. I can’t remember half of it, and one or two of the stories I have about my life I’m not quite sure that they’re true, or whether one time they seemed like a good story and now they’ve become truth because I’ve told them so often.”

“I’ve had lots of experiences of people telling me events and I have no recollection of them whatsoever. It’s that Virginia Woolf thing – you have great periods of cotton wool. You look back on your past and there’s all this cotton wool and suddenly you have this moment of being. That turn of phrase – ‘moments of being’ – that’s the thing you put in this book. The rest of it’s just fuzz.”

*

There’s a moment in Who Was That Woman where Ngaio is encouraged by a nurse to talk to her mother. “She needs to try harder,” she’s told. So back home, she turns the TV off and presses her for the stories she remembers being told as a child, of what it was like living in Chicago as a girl. “Didn’t you say you heard Bessie Smith sing?” she persists. “Tell me about the speakeasies and the gangsters and the blues singers? Tell me about the prohibition?”

When she had told my brother and me about her life in America, years before, it had seemed so unlikely. This plump woman with her hair in a greying bun, in suburban Auckland – could she really have led such an exotic life? Our father, we knew from experience, was a liar, so we thought perhaps she was following his example. We had felt embarrassed. It was as if she had said she had been a cowboy, or an Indian, like the movies we saw every Saturday afternoon at the Crystal Palace where the Lone Ranger would call out ‘Hi-yo Silver’ and as he galloped away an observer would ask, ‘Who was that masked man, anyway?’

This is where the title of her book comes from. “It’s that idea of memory – who was she? Was it me? And I like the anyway, too. That sense of: it doesn’t really matter, anyway.”

*

There’s also the issue of her and her central character’s name. Born in 1940, Aorewa Pohutakawa McLeod does not have Māori heritage. As a child, when she asked her parents about her name, they said they looked it up in a Māori dictionary. “I don’t know if they did or not,” she says. “I don’t know where they got it from.” She’s never been able to find it in any dictionary or list of names. “I wrote, in fact to the librarians at Auckland University and Waikato, and asked if they’d heard of the name and they said no.”

“Looking back on it,” she says, “I feel that I’ve been surrounded by silence. People don’t talk to me by my name. They say hello and go on. I think it’s made me think of my identity a lot more than if I had been called Mary, or Jan – I mean, God, there are so many Jans!”

There's a short essay at the back of her book on the origin of her name. “People begin assuming that Aorewa is a ‘chosen’ name,” she writes, “and look a little shocked when I explain, ‘No, it’s what parents do to you. It was hell to live with as a child.’”

When I ask her if she wrote the book for the lesbian community, she says that it grew that way. “When Damien said it was kind of a history, I thought, well, you know, it’s gone. That community is gone. The seventies and the eighties and the nineties – and we lived through it and thought it was going to be there forever.”

At the same time, the book’s not cast in a nostalgic light. In fact, it’s wry, almost mocking. “I found that quite difficult,” she says. “To talk about the lesbian separatist community with its emphasis on therapy and therapy groups. I think it was a really genuine and important period in feminist history, but it’s gone now and it was difficult trying to get a balance between saying that it was something that had value and laughing at it. And I think if you’re writing fiction, you always have to laugh at it a bit. Otherwise it’d be really prosaic and people would say, ‘oh, that’s bloody boring’. I think most of the people who went through that time laugh along at it because we sort of realise how excessive we were being.”

On writing about a period in history that was hugely formative to the development of feminism, she says, “Lesbianism - you could say - came out in the seventies. Before that, everyone was closeted and hiding away, or just - in fact, there was no definition and I think that's one thing I felt came out in the beginning of this book. You know - we were sitting around talking about what made us lesbians. What were we? And all we had were vague Freudian theories. Perhaps we had cold, distant mothers. And we all sat around and said, well, yes, we all did have cold, distant mothers, but in fact it was only when feminism came along that we were able to start defining what being a lesbian meant.”

“A lot of the things that now seem quite funny about the lesbian movement of the late seventies and eighties is trying to define ourselves, you know - when everybody went around cutting their hair short, and you didn't wear make-up, and you didn't have perfume and you didn't wear high heels - it was all sort of an attempt to say 'What are we? Who are we? Are we some sort of third sex - in between masculine and feminine?” And now that's all kind of gone, but I can see why it happened, whereas now we can sit around and say, oh you know, there's a continuum and we're somewhere in between.”

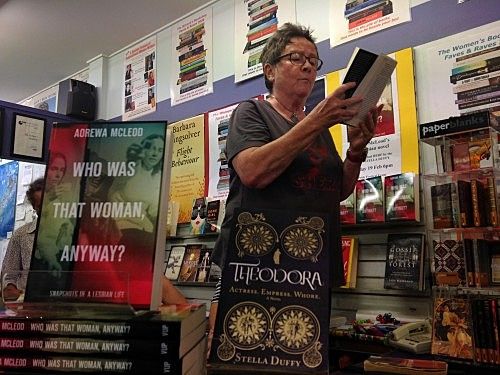

On the night of the launch, The Women’s Bookshop is more packed than I’ve ever seen it and hums with the jovial atmosphere of a family reunion. I count two men in the room when I arrive. One of them is Fergus Barrowman of Victoria University Press, the publisher of the book, and the other is a young man squashed in a corner of the bookstore looking trapped. I wonder if it’s her brother, and if it is, which one.

Aorewa stands on the front counter to read, and through it there are murmurs of delight, of recognition. At the end, she takes questions from the crowd. One woman asks if she’s going to write a sequel. Aorewa pauses. “Another book,” she says. “But I don’t think I’ve got a sequel. Unless I write about the last ten years of my life. But they weren’t nearly as exciting.”

“Hey!” Fran, her partner, protests. The crowd laugh.

“They were calm,” Aorewa says quickly. “And happy.”

Another woman calls out. “Do you have a favourite character in the book,” she asks, “Apart from yourself?”

“That’d be me,” Fran quips.

“In fact you didn’t need to say that,” Aorewa says. “Of course it has to be Fran.” She names a handful of other people in the room who also feature in the book, noting that when she’d told one of them earlier that night, she’d immediately rushed off to buy a copy. “Of course,” she beams suddenly. “That’s what I need to do! I need to go round telling everybody they’re in the book.” She blinks. “You are all in the book, of course,” she says solemnly. “Versions of all of you.”

Aorewa speaks at the Writers and Readers festival tomorrow with other Remarkable Women Meme Churton, Jacqueline Fahey and Jolisa Gracewood.

You can buy her book here.