A Vast Black River of Type: The Novels of László Krasznahorkai

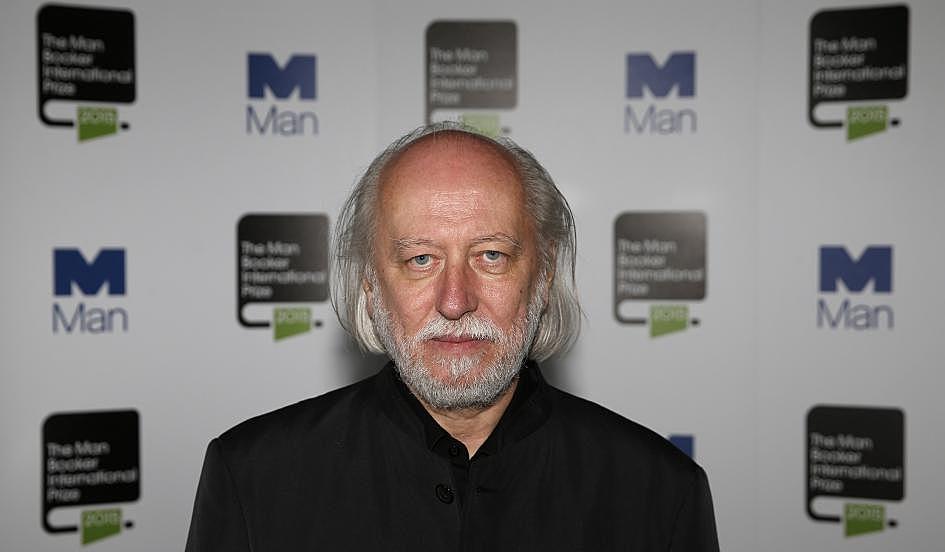

Redemption and its dissidents: Matt McGregor on the work of 2015 Man Booker International Prize winner László Krasznahorkai

Note: In referencing the work of Krasznahorkai, this essay refers to scenes of sexual assault.

When Hungarian novelist László Krasznahorkai was awarded the Man Booker International Prize in May, The Week ran a short essay with the glorious headline “Is László Krasznahorkai about to become huge?” The answer, in case you’re wondering, is ‘probably not.’ If Soviet Realism can be described as 'boy meets girl meets tractor' then late modernism from the Eastern bloc — such as the early novels of Krasznahorkai — might best be described as 'boot meets face meets mud'.

Such, at least, is the takeaway impression from Satantango, a pitiless debut novel set on a former collective farm in rural Hungary, ripe with drunks, rain and potential suicides. First published in Hungarian in 1985, Satantango has been followed by a dozen novels, as well as a handful of film adaptations with director Bela Tarr — most notably the cult seven-hour adaptation of Satantango itself — all of which consider the fates of eccentric minds in the midst of political, economic and cultural malaise.

From this first novel, one of only four translated into English, Krasznahorkai showed us his startling facility for long, complex sentences. In later works, these would become shambling and occasionally tame, packed with comma splice upon comma splice, riff upon riff lasting for pages on end; but in Satantango, they’re focused and tight, pushing just slightly at the edges of our attention to give us final clauses of astonishing potency.

In these early novels, you can find examples on almost every page. Here is Krasznahorkai describing a little girl on the estate where the novel takes place:

Esti, who kept looking back, saw him for a split second, his cigarette alight in his hand, like a comet fading, never to reapppear, its trace remaining for a few minutes in the dark sky, its outlines growing blurred, eventually absorbed in the heavy night haze that snapped its jaw around her now, the road beneath her immediately snuffed out so she felt as though she were swimming through the dark without any support, weightless, quite isolated.

Satantango is remarkably full of sentences like these. But Krasznahorkai is not only famous (by translated novelist standards, i.e. not famous at all) for his sentences, but for his ethos, which a postgraduate student might describe as ‘late-Soviet, Adorno-inflected modernism’, but which that same student, stuttering into his fifth beer, might admit was basically ‘bleak as fuck.’

Both descriptions are accurate. That first passage, quoted above, describes the final moments of a little girl who, for much of the first half of Satantango, represents the sole point of light in a community of deadbeats and drunks. We watch her plant a ‘money tree’ after being tricked by her older brother. We then watch her drown her cat. Finally, in a scene that occurs halfway through the novel, we watch her drink rat poison and die.

So, bleak — so bleak, in fact, that this novel has coloured the English-language reception of his later works, which has given Krasznahorkai the unfortunate and misleading characterisation as a writer who wallows in misery — a writer who is ‘post-apocalyptic’. But Satantango, along with the rest of Krasznahorkai’s fiction, is precisely not post-apocalyptic. There is no apocalypse, no grand event; there is no before and after; no golden age or hope for reform. Forget the bang; forget, even, the end: in Satantango, life goes whimperingly on (and on).

Forget the bang; forget, even, the end: in Satantango, life goes whimperingly on (and on).

But Krasznahorkai’s depiction of a generally immiserated and reified planet is only one part of the story. The other part — the more interesting part — is the rambling oddities and abandoned profundities of his characters’ minds. Krasznahorkai’s obsession with the flow of human consciousness explains much of the difficulty of his later works, which are both less dense than Satantango, but also much less conventional.

These later novels reveal a writer becoming gradually less concerned with making us astonished, and more concerned with showing us the failures of astonishment. They repeatedly depict characters searching, or waiting, for political or aesthetic redemption. While his characters suffer multiple disappointments, Krasznahorkai never dismisses their hopes, or condescends to them. To the contrary, on the evidence of these four novels, it seems like the unironic depiction of hope is at the core of his entire project.

This can be hard to spot: as I wrote in my review in 2012, Satantango is a miserable novel. This is also true of his second novel, The Melancholy of Resistance, which follows an unlikely group of loosely-fascist operators in a depressed Hungarian town.

Krasznahorkai establishes the novel’s — and the town’s — moral universe with his long opening depiction of a middle-aged woman, named Mrs Plauf, riding the train late at night. As she kills time on her journey, Mrs Plauf finds herself being watched by a man across the aisle. When she goes to the bathroom, she finds the same man trying to break down the door — in order, we realise, to assault her. Later, after she has returned to her seat, she hears a “dull thump” and realises that another man, also sitting nearby, has punched the woman he is sitting next to in the face:

That woman is slumped there unconscious, the sweat poured down her brow, the man in the fur camp is motionless, and so she stood helplessly, seeing only the window before her, the window-frame and her own reflection in the dirty glass, then the train, which had been forced to stall for a few more minutes, started up again and, exhausted by the furious succession of images, her mind buzzing,she watched the dark empty landscape swimming by outside under the heavy sky…

After this burst of violence, we follow Mrs Plauf on her walk through the city, which has “assumed the look of all cities under siege, where … the inhabitants have surrendered even the last traces of endangered human presence.” At this point, we are introduced to a faceless mass of people who have gathered in the city centre. As we learn later, the crowd is nominally there to follow a circus act — a touring whale: part overloaded symbol and part McGuffin — but increasingly comes to represent the rebellious potential of the excluded and unemployed. The longer the crowd stays put, the more the town’s politicos begin to fret.

The prime politico in the novel is Mrs Eszter, a mildly fascist operator who proclaims the need for social “renewal”. “We are,” she says, “on the threshold of a more searching, more honest, more open society,” a society with “fitness of body and a powerful and beautiful desire for the intoxicating realm of action.” Her various small-time machinations and manipulations — bullying various drunks, incompetents and her erstwhile husband, Mr Eszter — make up most of the novel’s plot.

But it wouldn’t be a Krasznahorkai novel if its plot wasn’t given far less space than its digressions, which are legion. The most peculiar of these comes from Valuska, the son of Mrs Plauf, who spends a good chunk of the novel variously going to the pub, wandering the streets and running errands for Mrs Eszter. In Valuska, Krasznahorkai shows his ongoing fascination — present in Satantango and truly indulged in War & War — for the loosely punctuated oddities of eccentric minds.

So, while we wait for the crowd to spill into violence, we witness these continuous “moments of exaltation as an insignificant inhabitant of planet earth … turning its face towards the sun”:

an exaltation so intense that by the time he finally reached the market end of the boulevard again...he wanted to cry aloud that people should forget about the whale and gaze, each and every one of them, at the sky.

While Valuska exalts and worries by turns, the crowd begins to grow restless. The fact that what is, nominally, a circus crowd, could pose a threat to the town — and the fact that its opposition is represented by so pernicious a figure as Mrs Eszter — gives us a sense of the political options presented by the novel, which are limited to two shitty choices: anarchic mobs or a police state.

Krasznahorkai’s point appears to be that life has degraded to such a point that none of the novel’s characters seriously believe that there is any decent way for them to live together — none of them, that is, believe there is any such thing as politics. And so, when masses of people gather, the town can only expect “the unstoppable stampede into chaos”, a stampede born of “an infection of the imagination whose susceptibility to its own terrors might eventually lead to an actual catastrophe.”

Mr Eszter, the weak and worthy husband of the plotting Mrs Eszter, gives voice to this lack of political hope. His world-weary pessimism — the mirror, he says, is “always reflecting the same world, dully turning back the sadness that rose in billows beneath it” — is both diagnosis and symptom of the general malaise of the town. Like Krasznahorkai, he is torn between dismissing the naive hopes of the townspeople (if not all of humanity) and mourning their eventual destruction. For they, in his words:

Could on no account bear their exclusion from some notion of a distant state of sweetness and light, were condemned to burn for ever in a fever of anticipation, waiting for something they couldn’t even begin to define, hoping for it despite the fact that all the available evidence, which everyday continued to accumulate, pointed against its very existence, thereby demonstrating the utter pointlessness of their waiting.

Mr Eszter insists on going big — later: “the whole of human history is no more, if I may make myself clear to you, than the histrionics of a stupid, bloody, miserable outcast in an obscure corner of a vast stage” — but it becomes clear that these outbursts are not quite the expressions of authorial truth that they might seem. Krasznahorkai shows his impatience with humanist optimism by putting its most execrable cliches in the mouth of the novel’s greatest cynic, Mrs Eszter; but the tame fulminations of Mr Eszter, who can barely gather the courage to leave his own house, are hardly more convincing.

It is only Mr Eszter’s sympathy for Valuska, and his growing obsession that no harm should come of him, that offers us any kind of human decency. But it would not be a Krasznahorkai novel if decency went unpunished. Krasznahorkai’s narrative technique here, used to similar effect in Satantango, is startlingly cruel: he begins by giving us plenty of time inside the mind of a character, only to make us witness, later on, that character suffer, in the background, with no eulogy or explanation. It is a bastard of a technique, and The Melancholy of Resistance is a bastard of a novel.

it would not be a Krasznahorkai novel if decency went unpunished

Published in 1989, when Krasznahorkai was just twenty-five, The Melancholy of Resistance is the last of his early, claustrophobically Hungarian novels. From 1990, following the end of Communism, his fiction begins to look outwards, particularly to China and Japan, and increasingly depicts an abiding and perverse search for aesthetic redemption. Despite — or perhaps due to — living through a period of profound political transformation, Krasznahorkai’s novels remains resolutely bleak about the fate of human community, preferring, instead to focus on, and occasionally wallow in, the potential of our art.

Regardless, Krasznahorkai remains a cruel writer. War & War, published in Hungarian in 1999, focuses on Korin, an archivist who goes on a quest to protect a curious, forgotten manuscript. We enter the story on a desolate Hungarian bridge, where we find Korin surrounded by a gang of armed adolescent boys. Here, as in Melancholy of Resistance, Krasznahorkai uses his opening pages to establish an atmosphere of violence, filtered through a typically eccentric point of view:

...and, furthermore, that it was only this, in its countless thousands of varieties, that did exist as such, that what existed was his identity as the sum of the countless thousand imaginings of the human spirit that were engaged in writing the world, in writing his identity… what was clear was that most opinions were a waste of time, that it was a waste of time thinking that life was a matter of appropriate conditions and appropriate answers, because the task was not to choose but to accept...”

As this chunk of a multi-page sentence suggests, War & War largely follows the dominant syntactical choices of Melancholy of Resistance. The talking-point from War & War is that each sentence is its own multi-page chapter, a restriction that means that, within each chapter, Krasznahorkai’s sentences have the chance to dive and bend with as much verve as his earlier works.

This decision, though, also means that sentences that don’t need to dive and bend — sentences that do ordinary novelistic work, and which don’t easily lend themselves to stylistic fireworks — read like the products of simple mispunctuation. Some of Krasznahorkai’s more workmanlike passages do not quite provide the vitality demanded by the form; as a reader, you often find yourself mentally adding full-stops to his sentences.

But the driving interest of War & War comes not just from its sentences, but from its plot. After the boys leave to throw stones at passing trains, Korin makes his way to the airport, where he fumbles his way into getting a tourist visa to New York City. The manuscript, he has decided, can never be safe in Hungary. He must take it to the capital of the world, where it can be archived in the safest place there is: the internet. After a long scene at the airport, where Korin spends hours in conversation with a flight hostess — which is related in deep detail, and establishes Korin’s considerable rambling charm — we go with him to New York.

At this point, the novel is shabby and strange; but it’s manageably strange: despite the single-sentence chapters and their irregular tangents, it never makes you want to throw the novel against the wall or condemn it, along with Gravity’s Rainbow, the Unnameable and the novels of Alain Robbe-Grillet, to that bottom shelf of impossible fictions.

But then, the novel takes a sharp, difficult turn. After we get to JFK Airport, where Korin is (naturally) punched in the gut by a stranger, he eventually finds an apartment with a young Hungarian man, Mr. Sárváry, and his unnamed girlfriend. This enables Korin to begin his project: to type out his special manuscript and put it online. While Sárváry goes to work — as a translator at the airport, and then, after he is fired, as some kind of low-level criminal — his girlfriend stays home, stirring what seems to be an endlessly simmering pot of stew, listening to Korin, logghoreic as ever, tell her (and us) his precious story.

And what of this story? It’s hard to know what to make of it. For the most part, it follows four travellers (through space and, I think, time) discussing philosophy and aesthetics. Here, for example, is a discussion on the grandeur of a cathedral:

...this was the truly startling, truly extraordinary thing, they said, this all-consuming idea that weak and feeble man was capable of creating a universe that far exceeded himself, since ultimately it was this that was great and entrancing here, this tower raised to soar beyond himself, and that man was capable of raising something so much greater than his own petty being.

Like Melancholy of Resistance, War & War never allows itself too much optimism. Directly after the soaring depiction of the cathedral, Krasznahorkai describes, in detail, Sárváry raping and beating his girlfriend. As if this juxtaposition wasn’t enough — the heights of aesthetic rapture set against such repulsive, misanthropic lows — Krasznahorkai follows it with Sárváry, the rapist, claiming to be “a video artist and poet.”

As Korin says later on, “All is false by now, he shook his head, it is all one lie after another, and these lies so permeate the most obscure recesses of our souls that they leave no room for expectations or for hope.” This diagnosis is not so different from Adorno’s: all that was singular has become reified; some forms of life are no longer possible; capital has processed and spat out the world and our lives are lesser for it. But Krasznahorkai sees the net effect of this reification as not middle class turpitude and stagnation, so much as brutal violence and exclusion. The assorted artists and outsiders across Krasznahorkai’s novels are not seduced or anesthetized; they are starved, imprisoned and murdered.

This conclusion is powerfully made in the abrupt shift in technique in the novel’s closing pages. In Krasznahorkai’s fiction, it is probably more of a spoiler to give away developments in technique than developments of plot. So, spoiler-alert: at the end of War & War, after Korin has uploaded his novel to the internet, we lose his long, energetic sentences and return, jarringly, to the world of deadened, functional prose. Never has the presence of so many full-stops been so astonishingly sad.

And so we trudge, with muddy boots and bloody knees, to the beginning of Krasznahorkai’s most recent novel, Seibo Down Below. It opens — surprisingly, given the shabby and violent openings of his other novels — with an extended description of a bird:

No one is looking, no one sees it, and if it’s not seen today, then it’s not seen for all eternity, the inexpressible beauty with which it stands shall remain concealed, the unique enchantment of its regal stillness shall remain unperceived…

The passage goes on to reflect on the possibility of an unmediated experience of “unbearable beauty,” a reflection shared by the novel as a whole, which is kinder, more avuncular novel that the others. It is less piercingly awful, and continues Krasznahorkai’s progression away from the dense, rhetorically complex prose of Satantango, to something lighter and less astonishing.

While it is about beauty, Seibo Down Below is Krasznahorkai’s least beautiful novel to date

While it is about beauty, Seibo Down Below is Krasznahorkai’s least beautiful novel to date. There is less weight on the content of his sentences, less significance to be drawn from the words. This means that we pay more attention to the form; it also means, somewhat jarringly, that we pay attention to the act of paying attention. In Seibo Down Below, Krasznahorkai never lets you forget that you are reading; there is no curling up, no sinking in.

A generous reader can only conclude that Krasznahorkai knows how much of an effort it takes, and he has some wider purpose for insisting that we make it. Throughout Seibo, Krasznahorkai describes in soaring and tedious detail the method of producing and experiencing various kinds of artworks, which include the production of Japanese Noh masks and the restoration of a statue of Amida Buddha. In so doing, he shows both the exacting dedication of the artists themselves, as well as our no less exacting desire for the objects of such dedication - i.e. the artworks themselves — to provide us with an experience of the sacred.

But Krasznahorkai is clearly unsure that the objects of art have such force or weight. It can almost seems as if Seibo were an attempt by Krasznahorkai to convince himself that art might ensure, as one sensei claims of the art of Noh, that “all that you could call transcendental or earthly is one and the same, together with you in one single time and one single space.” However, in a typically cruel juxtaposition, Krasznahorkai goes on to describe the sensei “counting out an enormous pile of money” — undermining much of the grandiose rhetoric found elsewhere in the chapter.

Seibo Down Below is, by a reasonable stretch, the least interesting of his four translated novels. Unlike his earlier fiction, neither its spiralling repetitions nor its runs of clauses are made to any great result. Indeed, in scrubbing his sentences of immediate affect, he has sometimes scrubbed them of their worth. The open question of Krasznahorkai’s novels, though — and it’s a question that can be posed to much contemporary avant-garde fiction — is whether the content is as audacious as the form. To put this another way: despite the long sentences, is Krasznahorkai really saying anything all that different?

Across his four translated novels, there is an abiding impression that both the world — that vague, ill-defined thing — and the people in it are getting worse, and that there is nothing in our current political economy that is capable of doing anything about it.

The immediate answer is: not really. The explicit social critique in all of Krasznahorkai’s novels is, at first blush, comfortably modernist, and it comes as no surprise to see him name-check Adorno in interviews and provide a generically techno-dystopian view of the world. (From an interview with the The Guardian, while pointing to the journalist’s computer and microphone: "This is the result of 10,000 years? Really? We have microphone, laptop, this technical society – that's all?”) Across his four translated novels, there is an abiding impression that both the world — that vague, ill-defined thing — and the people in it are getting worse, and that there is nothing in our current political economy that is capable of doing anything about it.

But there is more to Krasznahorkai’s novels than this bleak truism. Their reception — encouraged by his generally gloomy public comments — has tended to circle around that ‘post-apocalyptic’ tagline; but the dominant theme of Krasznahorkai’s works is not their depictions of malaise, but their depictions of eccentric minds searching, desperately, for redemption. It is this search which animates his prose, which is singular and astonishing, even when Krasznahorkai himself seems to be most suspicious of astonishment, even when he shows us that redemption is not possible.