Picking at the Surface

Van Mei on compulsive grooming, beauty and survival.

Van Mei on compulsive grooming, beauty and survival.

I watch my mum from the upstairs window as she bends over a patch of dirt and upturns the earth. She works late nights as a software developer, so these hours in the garden are hers. Determinedly, she pushes her knees into the concrete and pulls a weed out from the soil bed. An hour later, she is still scouring the earth, bundles of limp roots swelling beside her.

Some of my most intimate memories are watching her weed her own body, absently playing with her hair in the rearview mirror. She wraps the thread around her finger and pulls. I watch my uncle do the exact same thing on holiday in Malaysia, retrieving a tweezer from his dashboard at an intersection.

*

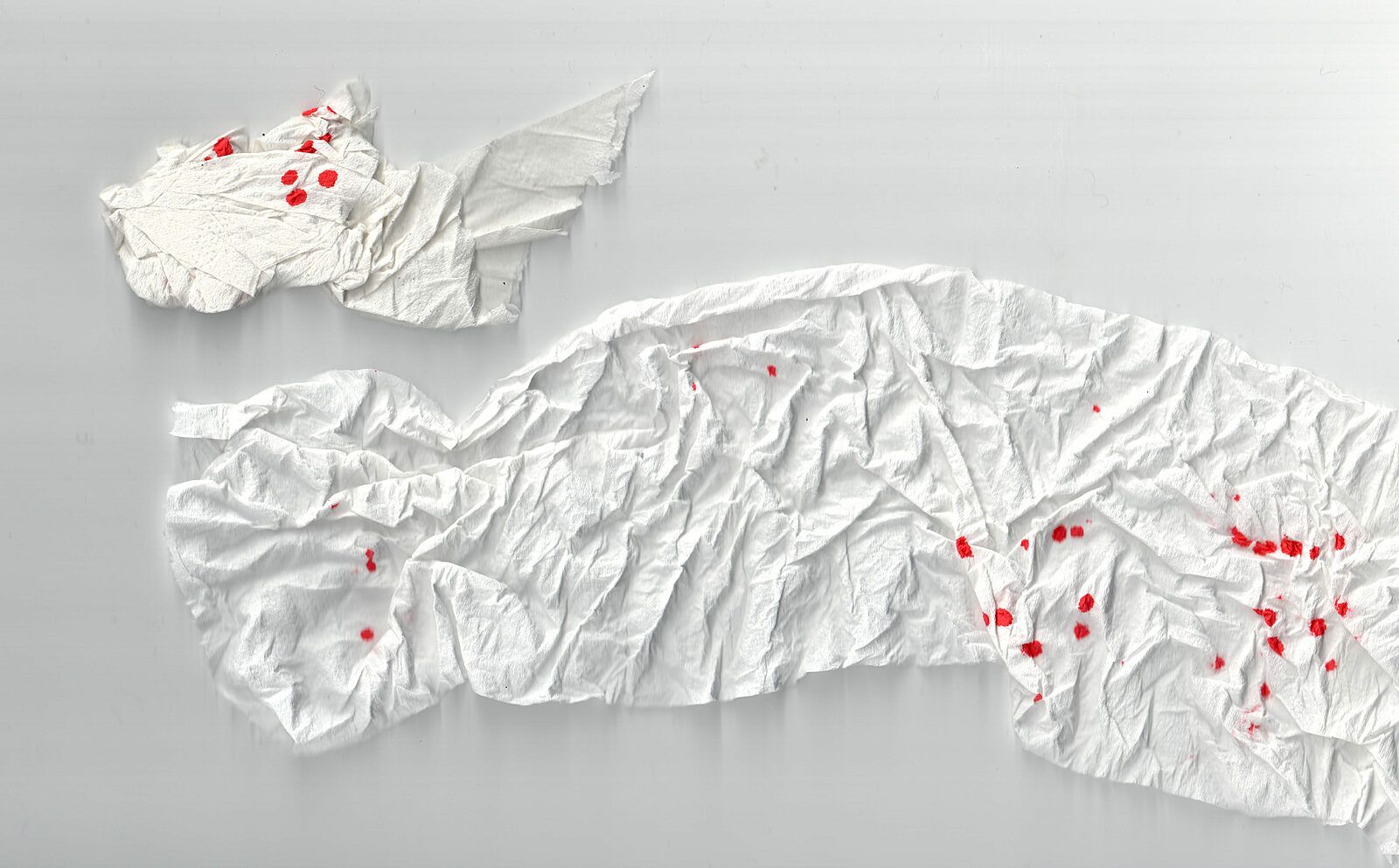

I am standing in a bathroom clutching a tissue to my face, watching small red dots appear on it like a pointillist mosaic. I’ve picked at my face too hard in the mirror and have to wait for the bleeding to abate. I wonder whether anyone will notice my prolonged absence, the fresh new marks on my chin or the tissues in the rubbish bin. Sometimes the act of picking is so unconscious that I pull my hand away from my face at work to realise my sleeves are stroked with blood. I don’t want anyone to see me like this.

*

In an essay written for the exhibition Not the Camera, But the Filing Cabinet, Dunja Kovacevic writes of skin picking in relationship to trauma and identity, that revulsion has its own allure. “I see myself bloodied in the mirror and sit with my hurt. In this state, I no longer look like me. I look like hurt.”

Hair pulling and skin picking have different scientific terms, but they both fall under the same umbrella of body-focused repetitive behaviours. The term describes, “a group of related disorders...not habits or tics; rather...complex disorders that cause people to repeatedly touch their hair and body in ways that result in physical damage”.

We are witnessed and we are witnessing, hyper-visible and desperately in hiding

What makes me pick pimples until they scar is the same unconscious drive that forces me to pull out my hair in clumps. These compulsive behaviours converge at the mecca of control, addiction, desire, shame and agency. Hair pullers, nail-biters and skin pickers re-affix our identity through compulsively shedding our own physical borders. Skin, the largest organ of the body becomes the public meeting room where habits run havoc. It feels like having all your intrusive thoughts broadcast facially. We are witnessed and we are witnessing, hyper-visible and desperately in hiding.

In his autobiography In The Dark Room, Brian Dillon revisits the psychological origins of the relationship between skin and emotion. The idea that the skin is the visible expression of the unconscious, he explains, has its origins in the work of the French psychiatrist Jean-Martin Charcot. Charcot corroborated evidence to support his beliefs, at times literally inflaming the skin of his patients in order to confirm the notion that the flesh could speak its pain. His contemporary, Freud, believed that the secrets of the unconscious world “would slip out, unnoticed, in a vast array of tiny clues and ciphers...a conduit from inside to outside.” Dillon imagines the relationship to be more interactive than directional. While the skin expresses the self, he muses, “it might equally be accurate to say that the self is a function of being in one’s skin.”

*

To understand what makes good soil, you have to go deeper than the surface – wobbling through an equilibrium of pH balance, nutrients, moisture, and the attendant needs of different plants. Good skin is all surface: pale, poreless, glossy as a disco ball. Good skin smoothes over discomfort, as if we can BB cream structural oppression into disappearing. It doesn’t scrape or bind, unlike when you’re forced to smile through a white man’s racist tirade because he is like family, okay? And because he is driving you home. It is the girl from the Moccona ads, wearing lingerie with no underwire, holding everything in. Does she have IBS, and did that coffee give her indigestion?

When I make a concerted effort to stop picking at my face, people tell me I have good skin. They tell me this in the same voice as if remarking that I am loyal, or kind, or consistent. This all changes when my picking becomes its most aggressive. Their eyes stray from mine, uncertain, to settle on my chin.

The first function of skin is a barrier: it’s how we filter and protect our organs from temperature, radiation and chemicals. Its second function is as a regulator, assessing and controlling our internal and external environments. Thirdly, it’s a sensor in how we physically commune with our surroundings. The barrier of skin is not without its ozone holes, and neither are our identities. We are always affected by the air between us, by the people we share breathing space with, by what is happening.

*

There is one night where I am unreasonably awake at three in the morning, and on Tinder. I swipe past multiple white men proudly holding up dead fish, who would be the first to get voted off Survivor. I swipe past a guy in a bar desperately clasping onto the hotness of the girls beside him. I swipe past someone I know who studies law but is honestly boring and probably votes National. An image of one of my previous abusers shows up next. I have not seen his face in over a year. I think about how I dared not say his name for nine months in the therapist’s office and have constructed my life around avoiding him. I wonder if he has seen my profile. As an act of self care, I do deep breathing exercises, drink peppermint tea, text my friend for the morning, calmly place my phone to the ground and decide to watch some television. It is only when I pause on the tenth episode of Aggretsuko that I realise. I have dug my nails into my palms so hard there are moons all over my lifeline. I have pulled out more than half of my pubic hair. It is a shock to look at myself and see myself wounded. I look like hurt. I look like unbelonging.

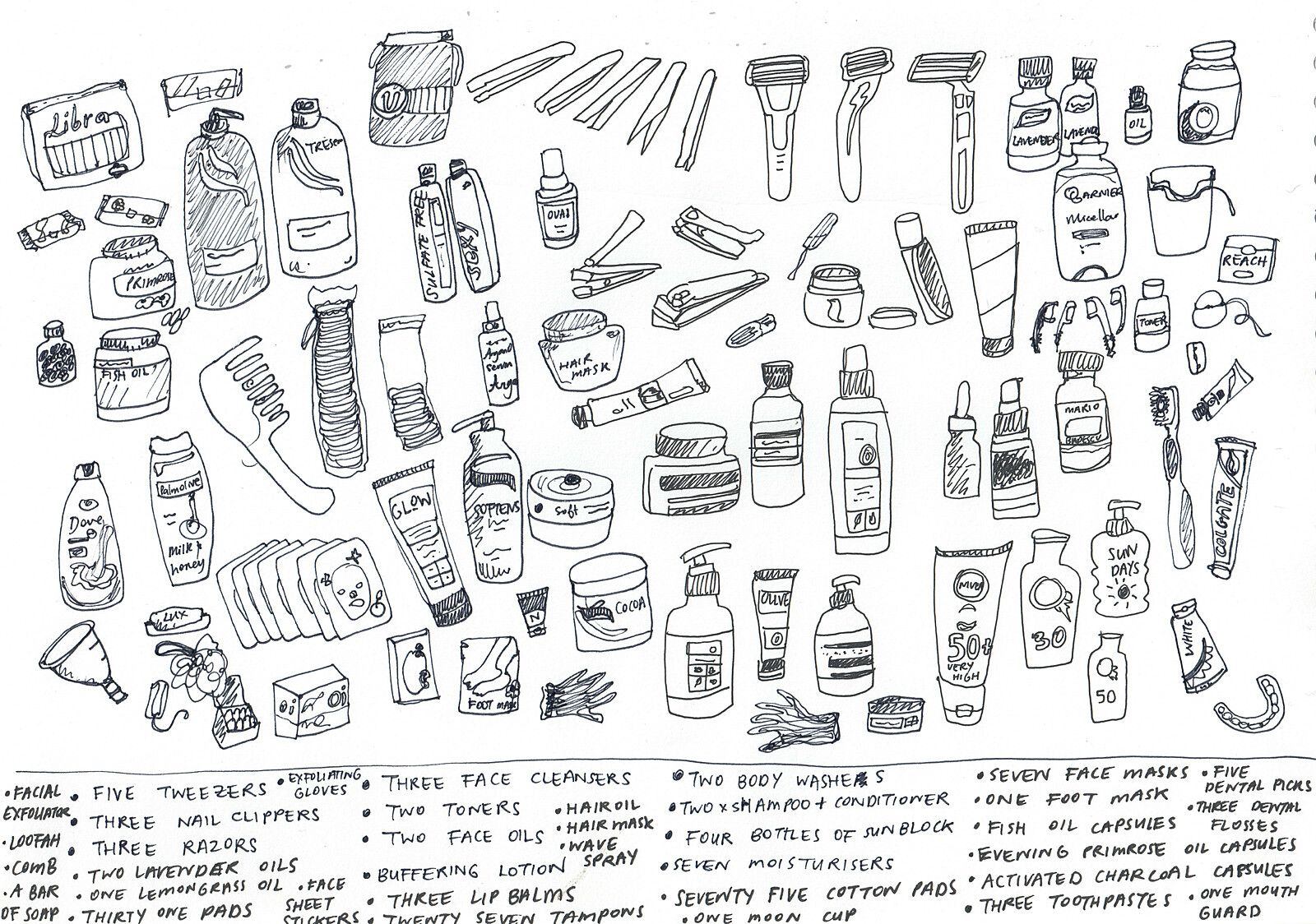

In the period following this, I buy about $300 worth of skin care. Mostly, I buy cleansers.

*

*

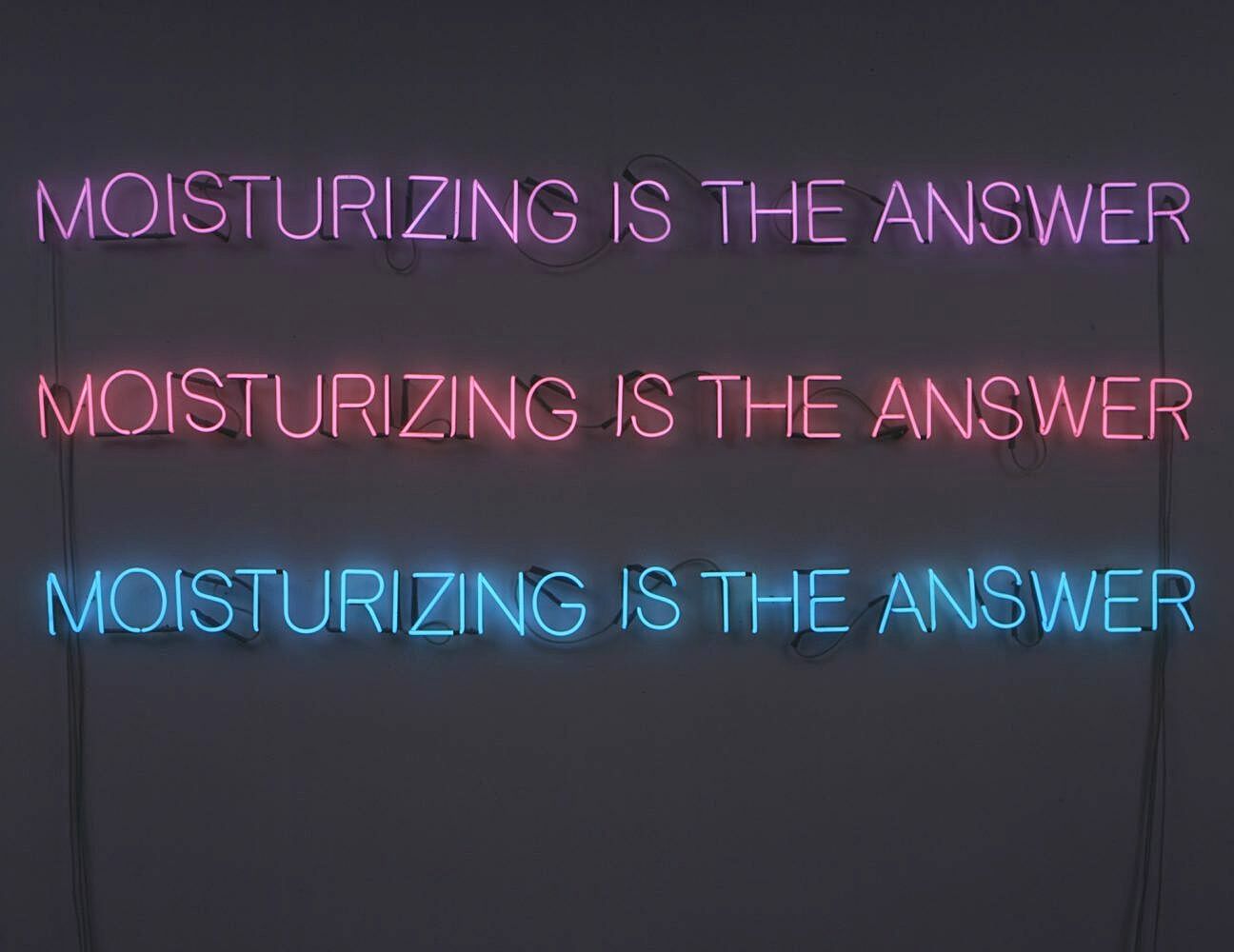

Skincare is the gentler sister of skin picking. For those of us unaffected by larger skin disorders, moisturising can be an affirming and enabling ritual of identity. Jia Tolentino writes for The New Yorkerthat her improved skincare routine is a “ridiculous attempt to affirm to myself that I will outlive the Trump Administration”. “[Skincare makes me] feel like I’m somewhat in control of my own destiny,” states Alison Roman in the article.

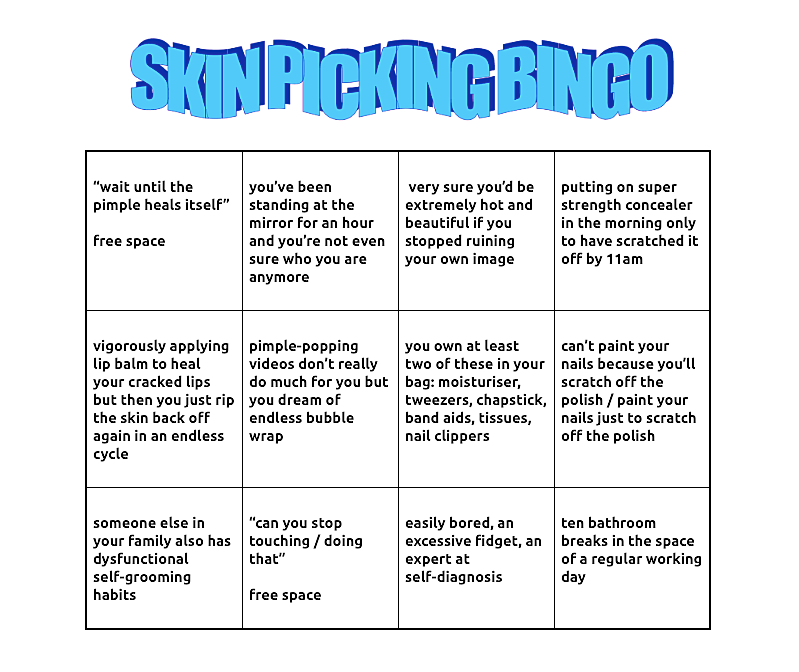

You can read your acne like an astrology chart. I think that young people in general are obsessed with filters, memes and horoscopes because it gives us a sense of being in control – of knowing the systems we’re operating against. The term cosmetics arises from the etymological root kosmos: to order or arrange. Later in history, the use of the word becomes closer in meaning to adornment and anointment. Cosmos, the order and harmony of the universe, also originates from kosmos. Cosmos suggests that all things unfathomably minute and colossal have a specific plan and place in the worlds we live in. Cosmetics suggests there is a correct way we can live in a body.

Kovacevic writes that “perhaps our cultural fascination with poreless, unmarked, skin is similarly located in a longing for a return to innocence.” It feels telling that a massive portion of current mainstream beauty trends seems to be about the augmentation of women’s dewy-natural-already-conventionally-accepted selves. Fascination with our skin has gained ground at alarming rates. Hannah Banks-Walker reports that women are spending more than ever on facial skincare products, with billion-dollar industry figures in the UK alone predicted to increase 15 percent by 2023. And where better to go birdwatching than on social media? The performative act of putting on a facemask (exhibited online by your younger, savvier friends) feels like manifesting a second skin. It is a desire to be on-brand, to articulate a certain kind of class and sensibility, to own a digital lexicon, to have taste, to be good. Skincare tells us: I take care of myself.

But moisturiser is not mascara. In an essay for Real Life Mag, Rina Nkulu sums up the difficult relationship between the two. “Beauty products that live on you can be removed. Those that live with you have to be evicted, broken up with.” Skincare is a seamless accentuation of ourselves, a mask of construction and competency that we only remember we’re wearing once we get to the bottom of the bottle. The latest face masks exist digitally, above the surface of our self-posed images. User Johska’s popular Instagram filter BEAUTY3000 imagines self-care through the glow of cyber reality. Photographic filters act as facial primers, difficult to turn away from. We reinvent ourselves through invisible modifications, harder to spot by the light of day. These self-soothing mechanisms establish our identity as much as our compulsion to wound unhinges them.

*

In her popular Buzzfeed article that made rounds the world over, Anne Helen Peterson speaks to how millennials have become the Burn-Out Generation. “The most common prescription (for burn out) is ‘self-care.’...but much of self-care isn’t care at all: It’s an $11 billion industry whose end goal isn’t to alleviate the burnout cycle, but to provide further means of self-optimization.”

Look in the mirror to find the apocalypse. There isn’t enough room in our culture to metabolise shame, so we’ve turned to skincare to cure our topographical feelings. The billion sheet-masked ghost portraits on Instagram alone attest to symptomatic stress more than anything else I’ve seen – and my picking speaks about coping with pain more than I can otherwise express. I’m a Libra so you can call me vain and consumerist, but these days, moisturising seems easier and less expensive than talking to somebody.

Anne Helen Peterson, Burn Out author, comments on how Marie Kondo is spearheading self-optimisation in our homes. She doesn’t love her, but I do. In Kondo’s book, The Life-changing Magic of Tidying, the author writes that “when we really delve into the reasons for why we can’t let something go, there are only two: an attachment to the past or a fear for the future.”

*

*

I’m afraid that climate change will swallow us whole and I won’t have enough SPF 50+ sunblock to keep my skin from drying out. Then the world will be dying and I will still look ugly.

On our secondhand sofa, from where I normally watch my mother garden, my sister is curled up in the lounge light. Her body is contorted over a small compact mirror. Her fingers are talons, aggravating blackheads over and over until her whole face has been appraised. It’s like watching a student rhythmically writing on a blackboard: I will be good. I will be good.

I know that skin-picking and hair-pulling are both hereditary. My friend tells me to stop doing that but I don’t know how to. I think about how my grandfather and his ancestors moved and laboured across oceans, how my family survived colonial powers so I could maul my face off and spend their inheritance on ten-step beauty routines. Doing cardio in the hotel room. It’s the daisy game of love me/love me not. Would they love me if I had no cellulite? Every body part is a singular polaroid.

it’s too fucking hard to live inside my body

In the New Yorker article, Jia Tolentino includes a quote from beauty writer Arabelle Sicardi: “Beauty is a tool that tends to serve those in power...and, at the same time, it fundamentally involves acts of witnessing the body, helping it to endure its conditions.”

Living vicariously through a hologram appearance because it’s too fucking hard to live inside my body. Young women who care about their skin are seen as self-obsessed and narcissistic, but the world is complex these days. We’re not sure when exactly the rug is going to be pulled out from underneath us, when the tsunami is going to wash over us, or we’re going to run into the kinds of trouble we can’t just loofah our way out of. Our bodies are the first places we learn how to cope and the first places we know how to assert, to puncture and to organise. You see tweezers, but I see survival.

This piece was developed through Summer Fling, our mini-mentorship programme, supported by Foundation North.