The Forces Running Through: A Conversation with Pip Adam

Kiran Dass talks to Pip Adam about her novel The New Animals, hairdressing, narrative structure, Max Key's vlog, teaching to people affected by crime, and the terror of being a faker.

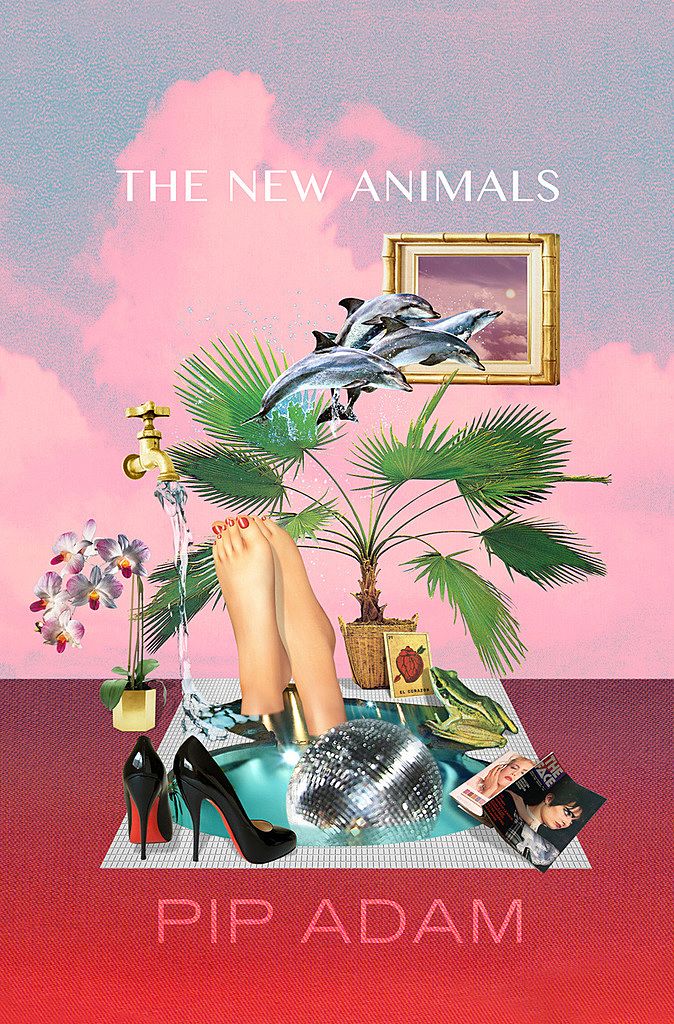

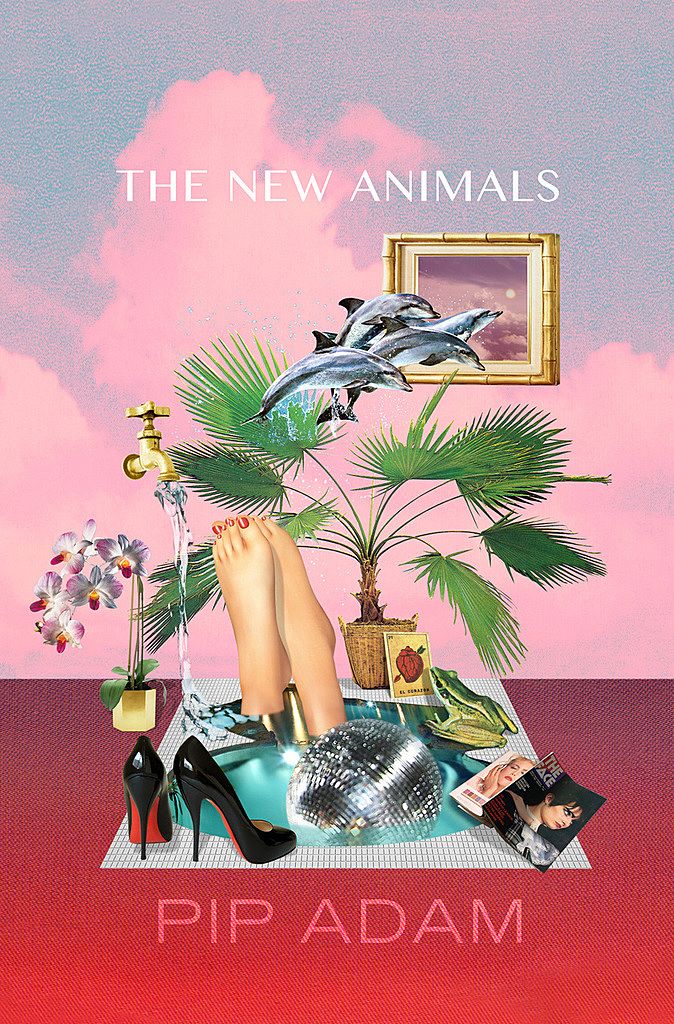

Pip Adam's latest novel The New Animals has divided reviewers. It's an experimental story set in Auckland's fashion scene. Our reviewer Briar Lawry called it 'compelling' and 'beautifully executed,' and David Larsen for New Zealand Books praised the novel as 'sure...strong' and 'bold.'

Other reviewers have been less flattering of Adam's work, which writer Carl Shuker responded to with a blistering essay. He fumes that 'when a writer of this talent is repeatedly misapprehended with such self-confidence we know something is wrong... What the fuck are we doing in this country when we are not reviewing and talking about this book?'

We #StandWithCarl. In the following conversation, Kiran Dass talks to Pip Adam about The New Animals, hairdressing, narrative structure, the uncanny, Max Key's vlog, and teaching people affected by crime.

Kiran Dass: I just finished reading Solar Bones by Mike McCormack and I thought it might interest you. It pushes what form a novel can take, and the protagonist is a civil engineer who looks at the world from an engineer’s angle, considering structures and environments. I'm thrilled an experimental novel from a small Irish independent publisher has been longlisted for the Man Booker Prize. Your PhD explored how engineers describe the built environment. Have you heard about Solar Bones?

Pip Adam: Thank you so much for this recommendation. I've just read a sample of Solar Bones and I’m hooked. The whole genesis for my PhD was a sentence I read in an engineering book that said, 'Civil engineers see the world differently.' I think it was a throwaway line, but I love the way McCormack seems to re-invent language to try and show this different way of seeing the world. It looks so good on the page too, eh? I love it.

Can you tell me a bit about your interest in buildings and engineering? And about how it relates to your writing work?

I grew up in around buildings and I had this strange thing that writing 'real' writing was about nature. When I lived in Christchurch I used to try and get to nature – usually somewhere like Arthur's Pass. I wrote poetry in those days, and I had this idea that if I wasn't writing about nature I wasn't writing poetry. It's ridiculous when I look back on it now – I think it was tied into my obsession with Romantic literature.

This word 'awe' was one of my favourites; the idea of the terror and beauty of capital 'n' Nature. And then of course I started reading stories set in the city and I started writing fiction and it all went very small and in people's flats and houses and cars. But after I finished my short story collection Everything We Hoped For I had this weird pull toward the awesome again and I thought of Arthur's Pass.

I remembered that my friend had worked on the Otira Viaduct and I thought, 'He will understand the Nature there,’ and instead he sent me photos taken while they were building the viaduct and I was like, 'Woah!' and then I started looking at buildings around me and I was like, 'Woah!' and I got some of that awe for the built environment. And I still get that, especially with that little bit of engineering knowledge I gained. The weird facts I learnt about concrete makes me love concrete, makes me look at it like a magical object.

The weird facts I learnt about concrete makes me love concrete, makes me look at it like a magical object.

It's interesting to think about how that interest relates to my writing now. When I was writing I'm Working on a Building I was totally immersed in it and when I finished it, I thought I had sort of washed it all off, but I can't unlearn it. I find it hard to be in building now and not imagine I can feel the forces running through it. I find it hard not to think about the way footpaths work.

So, yeah, it's hard to explain, but while I'm interested in writing people there's this pull to the inanimate as well. Like, with The New Animals I had to have the buildings first and I visited them lots. The workshop where Sharona works and Tommy lives is one of my favourite buildings in Auckland. I found out one time that you can see it out of one of the windows in Artspace and yeah, I just love that building and the flats Carla lives in. I love the way lots of things in Auckland are renovated into living spaces and intro smaller living spaces; I love that weird Frankenstiening of buildings that's taking place.

You are often referred to as an experimental writer. I'd love to know about your approach to narrative and form and their possibilities.

I'm really interested in what I think is called the 'uncanny.' I'm going to make a hash of this because people tell me things and I read things and they go into my head and I make up things around them but here goes – someone told me this story that Freud walked into his bedroom one night and saw another man there and got a fright and then he realised it was his reflection in the mirror – and that feeling he got in between seeing the other man and seeing himself is the uncanny.

I love things that are slightly off. Often the things that give me this feeling are paintings of people. The first time I felt it was when I saw Lucian Freud's paintings, and at the moment I'm really loving the work of Lu Cong. I also love Boyd Webb, and of course Yvonne Todd just always hits me where it hurts, where it really rattles this 'uncanny' thing in me. What I'm interested in is that it's not the fantastical or the abstract that makes me feel the world is odd, but the 'real' the hyper-real in some circumstances. So, yeah, I think my approach is this 'hyper-real' approach.

I want people to never forget that they're reading a book…if they do sink into this illusion the prose or the narrative will wake them into that moment between the story and the book.

I was recently criticised for my 'hyper-attention' and it was suggested this was something that should have been corrected in editing, but this is really exactly what I'm aiming for. I want the work to sit in that place between seeing the story and seeing the book. I have no desire to create an illusion; I'm not interested in making work that a reader can 'sink into.' To maintain that 'slightly off' feeling I want people to never forget that they're reading a book, that this is an artifice and if they do sink into this illusion the prose or the narrative will wake them into that moment between the story and the book. I think this is always my approach, if I have one, I want the language to stay visible, I want the narrative structure to stay visible, but only just.

Tell us a bit about the title The New Animals.

I have Holly Hunter at Victoria University Press to thank for that. For its whole life (and I wrote this book three times) it was called Tragedy of the Commons, but that just didn't work. And I was terrified about renaming it, but, as I remember it VUP publicist Kirsten McDougall said, 'Holly has a title,' and Holly said, ‘The New Animals’ and it was like it had always been called that. They started explaining why it was a good title but there was no need – it was just the title.

The book is a lot about fluidity for me, fluidity and physical change – I'm obsessed with how external factors can change our bodies (sunburn, hair-loss, freckles, they way sucking your thumb can change the shape of your jaw) and the idea that these external factors change our bodies into new animals really appealed.

The book cover by Wellington artist Kerry Ann Lee is great. I love that the issue of The Face on there has Siouxsie Sioux on the cover. That was a choice issue, too! It had the Mo-Dettes, Echo and the Bunnymen, the Human League and Viv Albertine in it. Did you specifically approach Lee to do the cover?

I am a huge fan of Kerry Ann Lee's. I didn't think it was possible to like her work any more than I did, and then I got this amazing opportunity to work with her during Porirua People's Library and I realised that so much of her art is in the way she does things. It was an amazing experience. So I became this embarrassing combination of fan and friend. I have that a lot in my life. Giovanni Tiso once wrote that his headstone should say, 'He was surrounded by talented people,' and I feel the same way.

Anyway, I said, ‘Could Kerry Ann Lee do the cover?’ I was thinking about the amazing book design stuff she does and my publisher Fergus Barrowman said yes, and he approached her, and then it became a a mystery to me because they did it all, then I got the cover and I just about lost my mind. It's an amazing image.

The New Animals is strikingly contemporary. It takes place over one day in August 2016, and doesn't have the benefit of hindsight. It feels very 'in-the-moment' and takes place in what feels like real time. Why did you decide to set it 'now' and what kind of benefit for you as a writer did it have being set in such a short amount of time?

Going back to that idea of the 'just off,' my friend found a book in a library once which was a biography of Hitler written in something like 1930 and that has stayed with me. Like, how odd must that book be?

I liked the idea that I could write a book set in one day and to have to stick to that one day, no matter what else happened. I like that it gives it this weird 'so contemporary' 'so old-fashioned' kind of feeling. Like how we look at what we thought a month ago with hindsight and think, ‘Oh I was so naive!’

I love your study of friendship in The New Animals. Platonic friendships can have complicated dynamics. Friendships can be uneasy and bound by history and social dynamics. What did you want to explore with the friendships in the book?

For a couple of drafts, Carla and Duey had slept together and it just felt so um, complicated. I started thinking about friendship and how I joked as a twenty-year-old about how you can't break up with friends, and I liked the idea that maybe Carla and Duey's relationship wasn't hitting some major barrier, it was just wearing out. We talk about that in romantic relationships – about just not being that into someone any more; I loved that idea that this could happen in a friendship, and exploring a really intimate relationship with no sex in it. Like what happens when we remove that from the equation? What does that look like?

Your descriptions of Auckland are impressively detailed. You're Wellington-based, why did you want to set the book in Auckland?

I love Auckland. I lived there for 20 years, and I did a lot of growing up there and I visit my family up there often. I wanted to write about money, well the economy, and I feel like Auckland is the business capital of New Zealand. Also, there are things about Auckland that I haven't found anywhere else in New Zealand; things about Auckland I miss very keenly.

I really wanted to spend some imaginative time there and experiment with that alternate version of myself that never left. I guess also, that is the city I did most of my hairdressing in, so that part of my life seems like it is there. I worked in Christchurch as a hairdresser as well, but I really felt like I was a hairdresser in Auckland.

The book is very funny. I laughed at some of the descriptions. ‘The whole of St Kevins Arcade was awful now,’ – those ghastly tiles and lightboxes. Gentrification in action, right?

Yeah. Although ... some friends and I had a pretty frickin' awesome lunch at Lord of the Fries there the day after Sigur Ros (laughs). I'm of an age that started going to gigs right after punk finished. I saw some amazing bands, but there was always someone, slightly older, saying, ‘Oh, but you should have seen...’ I love the name of that Brannavan Gnanalingam book – You Should Have Come Here When You Were Not Here.

I once said to writer Carl Shuker, ‘Man, we grew up with the best music,’ and he said, ‘Doesn't every generation think that?’ That stuff about St Kevins Arcade, and kind of the whole of K' Rd, it freaks me out, but I don't want to be a dick about it (laughs).

The fashion industry provides a great satirical backdrop, too. The bit about the white t-shirt cracked me up. When the stylist asks, ‘Does it feel fresh enough?’ You worked on fashion shows as a hairdresser/hair stylist. Did this really happen?

I didn't work a lot in the fashion industry – I did some work for a photographer and some shows but really I was mainly a Duey type of hairdresser (not as good but I worked in salons). I loved the fashion side of things. Those conversations in the back rooms pouring over Face magazines, talking the newer apprentices into letting you try a new haircut out on them; I loved that shit but there was a line. There were definitely people who I thought were wankers – some people who were maybe fakers.

I was terrified of being a faker, maybe I was a faker, but there were people who always talked a lot, and I might look at someone I trusted in the room and we would be like 'faker.' They wanted to make themselves important above the fashion, maybe. Yeah, I don't know. Often I loved it. I have these fond memories of us all standing round a model, it would be late, we'd all be smoking, and we'd be staring intently at the model trying to work out that tiny detail that was holding the hairstyle back in last season. They were excellent times.

Tell me about some of the insights you gained working on some of these shows?

The thing that stands out is, and I am sure this was a certain moment in time and that modelling is not like this any more, how objectifying modelling was. A model's work was like intensely connected to their bodies. I was going through my own shit at the time body-wise, but I honestly went to a call once and a photographer said to a model, ‘Can you lose a couple of pounds by Sunday,’ and she was like, ‘Yeah,’ and she did, like the product she was dealing was her body and her body needed to change and she changed her body. It was a very strange thing to be in contact with.

The product she was dealing was her body and her body needed to change...It was a very strange thing to be in contact with.

Did your hair clients confide in you a lot? I've always been fascinated by the hairdessing trade because it seems like being a journalist or a bookseller – you have to be 'on' at all times and you are the recipient of confessions. There's the technical and craft side, but I imagine it to be emotionally and physically demanding work. There's nowhere for you to hide – you can't have a bad day technically or emotionally. As a hairdresser, what is that kind of emotional engagement and client intimacy like?

I'm not sure how to answer this question without incriminating myself. I started hairdressing in a time when 'professionalism' was really important. Like you have a professional distance from your client – 'like a dentist' they often used to say. You should talk about their hair not their private life. And this suited me so well. I had this weird self-destructive thing where people terrified me. I couldn't handle school because there were people there so I left school and became a hairdresser where there were PEOPLE! But the professional thing I could do.

There is an invisibility when you're a hairdresser like this. People forget you're there and they let their guard down and I saw people behave in some pretty scary and sad and frightening ways. Also, mirrors – in most salons I worked at you could see every person in the salon all the time, and people are amazing when they don't think anyone can see them. So yeah, I was like this weird, robot that watched everything.

There's a science fiction aspect to The New Animals. On one hand you've got a social realist element but then also the science fiction side. How did you reconcile the two in this one work?

To me both parts happened as they're described. It was a real shock to me when people started talking about the 'figurative' journey. Like, I am cool with any reading, but I realised when people started saying that, that I had completely convinced myself that everything in the book happens on the same plane of reality. So I think that was how I reconciled it. I thought of the first half as social realism and the second as 'hard' science fiction. Andy Weir's The Martian was really instrumental in the book, as that was the sort of science fiction I was thinking about.

In the book you've got the two groups – the Generation X gang and the Millennials. I found that fascinating and even uncomfortable at times. And then, on the other hand, there's that idea in the book too of 'confidence over competence.' And not only the inter-generational differences but the other inequalities behind this. What was behind your idea of having these two distinct age groups – what did you want to explore?

It's interesting because, sorry I've said this a bit, I think of the book being more about class than about generations. I'd be insincere to say that I didn't mean to have the inter-generational stuff, it's there for sure, but what really interested me was what it is in our present moment to have money versus what it's like not to have money.

The main differentiation for me is that some characters have money, some don't. So I was really nervous that people might think that I think all millennials are loaded and have it easy, because I don't; it's this set of millenials. I find the categorising of generations so tricky. Like people bag baby boomers, but not every baby boomer was able to buy a house or had a great secure job.

In the same way, I get so fucking sick of people making grand generalisations about millenials. I guess in this situation, the one of the book, I needed a set of people who had made what society now would agree were poor life choices (not buying houses, not starting businesses, not investing) and were poor, and people who had maybe lucked into a situation where they had money and they'd used their talent to turn this luck into more luck. The split I saw was perhaps generational in this situation. Also, something I don't think many people notice is that there's actually three generations in that main group – I always think that Elodie is younger than Tommy; she is to Tommy what Tommy is to Carla.

In the book, the observation of the younger gang is that ‘they care crazily about things no one gives a fuck about – or should. That was why they ran the world, this is where we went wrong.’ But for the older group, ‘any kind of caring was frowned upon.’ What is your take on this?

Once, like maybe ten years ago, someone said to me I was too enthusiastic. They said, ‘Some people define themselves by what they hate. You define yourself by what you love.’ I don't think this was being said as a compliment. I spend a lot of my time being in awe of shit. Like, for instance, Max Key. I love Max Key's social media presence – I love his YouTube channel. A lot of my friends think I'm being ironic when I say this, cynical, but I'm not. I would be genuinely sad if Max Key stopped doing what he does.

I love Max Key's social media presence...A lot of my friends think I'm being ironic when I say this, cynical, but I'm not.

In this way I was a dreadful Gen-Xer. People used to take the piss out of me; I was called 'intense' a lot. So yeah, maybe I am embodying that in this sentiment. I fucking love the young people I get to hang round with. They get shit done in a way I don't think I ever did. I do think my generation, and by that I mean the people I hung round with, could be defined by our failures. When I was young band after band were being 'discovered' and then crashing and burning. Maybe its something to do with the drugs? Like heroin versus methamphetamine? Yeah, there was an awful lot of crashing and burning.

About two thirds of the way through, The New Animals turns itself inside out and spins everything on its head. It sort of pulls right out and there's a massive experimental shift. I loved it. Some people might hate it. Can you explain a bit about what you were doing here, if you feel you can without spoiling it?

So, when I think about it now, I think I only wrote the first bit of the book so I could write the second bit of the book. I needed the first bit to sort of make the second bit strange. I don't think it would have been as strange if the whole book was like that – it would have been a different book. I had this image, it was like a dream and it wouldn't go away and I just wanted to write it to get it out of my head. I don't think I had any greater aim than that.

Do you still facilitate writing workshops at Arohata Women's Prison? How has this made you consider the rehabilitative effects of writing and reading? What have you learned from doing these workshops – the challenges and rewards?

Yeah, this is an interesting question. I have still been writing with people affected by crime, inside and outside prison [with Write Where You Are]. I'm unsure if I have reached a conclusion concerning the rehabilitative effects of writing and reading, but I am sure glad they are writing. There are so many great writers who produce amazing work and I love reading it. So, yeah, as far as the rehabilitative effect on me goes I am very happy with it.

In these workshops we often facilitate in pairs or groups, and I have realised I love working this way. It's almost like being in a rock band. I love collaborating. I've also learnt to think on my feet. The main challenge I've found is that we’re working with really smart people who have great questions which I don't always have an answer for – like we have to work out the answer between ourselves, and really consider it. I love that.

I don't have an ounce of natural talent in my body – it's all from reading.

In The New Animals' acknowledgements you make specific mention of how ‘this book was written under the influence’ of Kitchen Venom by Philip Hensher, and Intensive Care and A State of Siege by Janet Frame. What impact did these books have on the writing of The New Animals?

State of Siege was recommended by writer Anna Smaill. I was really concerned that the last section is so much one person alone. I have always fallen back on my characters having 'someone to talk to' in my stories and I couldn't seem to make it work, so I asked Anna if she knew any examples of third-person narration where there was only one character and she recommended State of Siege. This is how I work – I am such a copy-artist. I think to myself, 'Who writes good food?' or 'Who does present tense well?' and I find and read them and I try and get that in my head so I can hear it in my own writing. I don't have an ounce of natural talent in my body – it's all from reading.

The New Animals is available from Victoria University Press.