Protesting, Sitting Alone, Talking Nicely: On Politics, Writing and Science

After attending the March for Science in April 2017, Tim Corballis writes about the different modes needed to participate in politics, writing and science.

It's election week, and we're all thinking, tweeting, and status updating about the election. In this funny and deep essay, Tim Corballis considers what it looks like to be a democratic citizen, from protest to sitting alone to talking nicely.

In early 2017 there was a series of ‘Marches for Science,’ organised in response to Donald Trump’s various attacks on the scientific establishment: funding cuts to, for example, the Environmental Protection Agency, the National Institutes of Health and NASA’s climate-modelling satellite programmes, all with direct effects on basic scientific research. I went to the Wellington event, the first in the world thanks to our proximity to the International Date Line. I arrived late, after the assembled crowd had begun the march from Civic Square to Te Papa.

My partner and I had joked about whether there would be chants: ‘2, 4, 6, 8, I think science is really great…’ etc. I’ve always found those chants kind of awful. I like and believe in protest, but I always found protests themselves a bit embarrassing – and the chants are among the most painful features. Numbers, just for the sake of some rhyme, like a kids’ book. (I like kids’ books too, but not as a model for political scriptwriting). So yes we made those jokes, and when I arrived on the scene there were a few hundred people marching, and, yes, there were megaphones and chants. I don’t remember the actual chants, but I think there were numbers involved.

There is something strange about the idea of a march for science. Science and protest don’t seem like obvious bedfellows.

There is something strange about the idea of a march for science. Science and protest don’t seem like obvious bedfellows. Really? A march for all of science? For private pharmaceutical research? A march for vivisection? For the Onco-Mouse™? A march for Richard Dawkins (which would feel something like a march for Margaret Thatcher)? A march for the Manhattan Project? I think I’ll leave it thanks. But there I was, marching, albeit in participant-observer mode (and I opted out of the chant). We passed a couple of teenagers. I overheard them discussing between themselves: ‘What’s this march?’ – with some excitement. Then: ‘Uh, a march for science.’ And away they turned.

So the problem is something like this: ‘march’ and ‘science’ seem to represent two different kinds of politics – the politics of the street and the politics of the lab. Marches are all about the people, the great egalitarian clamour for recognition; while science is all about the state, the big institution, the funding body. Science is done by scientists, not the people on the street, and science has by and large worked very hard at the distinction.

Scientific method generally insists on an effacement of opinion and individuality (which it calls bias). This is not in itself a bad thing, but it is a far cry from the ethos of a popular movement. The street is about bodily demonstration, in a public place, shorn of professional identities. It brings forth the sheer diversity of human need and being – it is a politics for messages and bodies who have been denied visibility. Science, taking place within well established institutions, jostles not for recognition but for funding and status and well-appointed facilities far from the everyday life of the city.

Of course the march was never really about science but about climate change, and about denialism, and about the sense of anger and impotence of those (myself included) who would have climate change taken for the serious danger that it is. So: march for climate change research? March against Trump? Well, why not? In any case, the march was surely a march for a very particular version of science: particular institutions (universities, not petrochemical companies), particular disciplines (ecology, climate modelling), and so on.

All this is fine, and only to do with words – the unfortunately broad name given to the event. Except that the march did seem to gather together signs and representatives of ‘science’ as a whole. There were placards with mathematical formulae on them, and jokey references to peer review – and, obscurely, a strange semi-literate sign declaring that ‘Sciece [sic] promotes fiscal responsibility.’ (Again: I’ll pass thanks).

There was a nerdy good humour about the event, an ethos that has struck me on occasion, to repurpose a phrase from Kim Stanley Robinson, as ‘science nice’. No black bloc here, no windows broken and, chants aside, no shouting and no spittle. The speeches – which included those from representatives of the Labour and Green parties – were unambiguously ‘pro-science,’ and implicitly or explicitly party-political. The honourable exception was a speech by my colleague Rhian Salmon, who acknowledged that we teach our students to take a critical distance from the claims of science. The final, big message behind the event, repeated by a few of the speakers, was an underwhelming ‘use your vote.’

And that’s the thing. There did seem to be a set of associations being made, in the march and in the air around it. Science had something to do with a vague, centre-left consensus, a Clintonian sensibility that, for all the range of actual policy positions, is also a Labour/Green one. It has something to do with decency, correct procedures and, yes, fiscal responsibility. ‘Science nice’ lines up with ‘politics nice’ (one that doesn’t always shy away from the desire to bomb poorer nations). Reason becomes reasonableness. The lab meets the street, and the latter is domesticated in the process.

My sense of remove felt... symptomatic for me of what it is to be a writer: to be in things and also not in them; to be half elsewhere at the same time, in the book that they might become.

I stood next to the poet Bill Manhire during the speeches. We listened with our arms folded. Bill paused to jot down the slogan about fiscal responsibility (I didn’t – which means I may have misremembered it). I was there partly as a writer, in that I was already intending to write something about the event. Afterwards, I asked Bill why he had attended and he said he was there to show his support – that he saw an association or parallel between the humanities and the sciences. That made sense. It made sense coming from Bill, who had worked and collaborated with scientists in Antarctica. It made sense in a lot of institutional contexts: the universities, the Royal Society. Presumably Trump doesn’t like the humanities much either.

At the same time, I wasn’t quite sure. I wanted to think about my sense of remove from proceedings. I felt a little guilty for my lack of enthusiasm. I’ve already talked about my general discomfort around protest – and indeed my scepticism about the whole deal. But there was something more too. My sense of remove felt very characteristic of my background in the humanities – a valuable negativity, a critical distance from things and a lack of satisfaction. This same sense also felt symptomatic for me of what it is to be a writer: to be in things and also not in them; to be half elsewhere at the same time, in the book that they might become and in the room where the book might be written.*

I want to think about all of this in terms of a three-way distinction I’ve come across. It originates in German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel – not that that’s where I read about it – and has to do with different national characters. I don’t think of it like that though. I think of it as a distinction in virtues, in patterns of thought, and especially in attitudes that can be brought to bear on a problem. For Hegel they are French, German and English respectively: French politics, German philosophy and English economics; or French revolutionary impatience, German introspective self-analysis, and English calm equanimity. I first came across it in Slavoj Żiżek’s book The Plague of Fantasies, where Žižek, a cultural critic, discusses it also in terms of toilet design:

In a traditional German lavatory, the hole in which the shit disappears after we flush water is way in front, so that the shit is first laid out for us to sniff at and inspect for traces of some illness; in the typical French lavatory, on the contrary, the hole is in the back—that is, the shit is supposed to disappear as soon as possible; finally, the Anglo-Saxon (English or American) lavatory presents a kind of synthesis, a mediation between these two opposed poles—the basin is full of water, so that the shit floats in it—visible, but not to be inspected. (3)

So I want to forget the banal and semi-racist ‘national characters’ thing then, however it might still fit some of our stereotypes. The whole distinction is after all to do with how we deal with our shit – as long as we understand that also metaphorically, to include any other problem substances or issues that are plaguing us.

We could think also about the kinds of situations that the distinction corresponds to: whether we are gathered in protest to call for change; alone and deep in our worries; or engaged in discussion, strategising and planning among colleagues. I want to forget about framing these modes in terms of national characters, and in fact characters and temperaments tout court, because I don’t think any one person or group fits any one of them neatly. We all have our times of anger, our moments alone, and our glorious shared conversations. I certainly don’t feel any of them on its own fits my temperament. I have trouble choosing. So I want to use other labels. And I’m tempted by the following: politics, writing, and science.

Politics means the left, of course. And it means the street, and opposition, and the desire for change; it means impatience and violence, the violence necessary to end other, deeper and more routine forms of violence.

Writing means thinking and self-questioning and working things out alone in a room; it means staying with the trouble long enough to solve it, or without solving it at all; it means contemplation and art and therapy. Before I go on, I will acknowledge that my labelling does involve an ad hoc violence with all of its words (politics, writing, science). The categories each cover a whole range of different virtues, bundling together inconsistent modes under very broad headings. It makes them loose-meaninged and slippery. It sneaks all kinds of assertions about a complex slice of reality into play with a mere linguistic manoeuvre. So, even as I continue to use the labels, I know they are wrong. But they are also right, or right enough, at least for the length of this essay.

Science then? Method and peer-review and observation and repeatability of experiment; the attempt to work out what we can agree on (what has been called ‘communicative rationality’); all kinds of conversation and reason and negotiation and exchange; measures and scales and instruments and metalanguages. Measurement also implies weighing up, which means equivalences and values – this for that – and economics. We know that science doesn’t really mean all that – after all, science is the sciences, as different from one another as field geology, big data and theoretical physics. But still, I will freight the word, for now, with those meanings.

Science, of course has its revolutions, and they are as violent in their own way as any. Politics, too, is not only about revolution but is also about utopia – the post-revolutionary time, when, yes, it will be necessary to work things out. Science and politics each contain their deeper reflections too… and so on. The complexity of any overarching distinction is that each term ends up trespassing on the meanings of the others. And to be sure, ecologists’ ‘scientific’ passions often border on revolutionary – though my sense is that they are generally oriented more toward policy, at bringing the state and the people under the direction of reasonable, ecologically informed thought. Ecology, after all, puts its desire for change into the service of a deeper terror of catastrophe which is, whatever the merits of either side, strictly incompatible with a bottomless revolution that would leave nothing unaltered.

The division of experience into politics, writing and science allow a rough and ready map of a terrain. It’s a map that’s useful to me personally, since it makes some sense of many of the places I’ve occupied through what passes for a career. Writing, to be sure, has been one of my driving purposes for the last 20 years. I’ve also been involved in Left projects such as, most recently, the journal Counterfutures, and feel a steady and partisan commitment to its politics.

This year I also had a change of jobs, moving from a teaching position in an art and design school and into a science faculty, where I’ve been working in a group that teaches and researches on science communication and the interface between science and society. I have had a tendency to drift and gather across various academic disciplines and creative practices – physics and maths in my undergraduate study, sociology, aesthetics and ‘theory’ in my PhD, creative writing and communism – and dividing that untethered career under the headings of politics, writing and science gives it a hint of purpose and order.

Politics, writing and science require incompatible modes of being.

Order is not the right word though. The tension between ecology and the revolutionary left hints at a larger incompatibility. Politics, writing and science require incompatible modes of being. As a leftist, I feel discomfort when I withdraw from the world to write and contemplate. As a writer and thinker I also feel discomfort in too-quick activism – in protests and chants. And it makes sense too of the complex discomfort I feel sometimes within the broad cultural milieu of the science establishment. I feel it when confronted by reasonableness of science writing, say, and the certainties it expresses. I feel it in the face of that air of knowledge and authority that surrounds many scientists. It is a discomfort that comes from a yearning both for the contemplative moment of writing, and for the impatient and angry gesture of politics. It's a discomfort about reason and reasonableness; it’s a yearning for both metaphysics and revolt.

The point of the threefold distinction is that, however much its virtues might come together in some broader place or practice, they are at odds with one another. Each offers a guide to behaviour, and each form of behaviour is appropriate to a situation, and you can’t do all of them at once.*

These headings of politics, writing and science also make some sense of the predicament that science finds itself in. My father, a senior scientist, has occasionally expressed a concern that people don’t like science. He’s not alone – other scientists and their supporters feel a similar frustration. What other reason for those marches? The frustration concentrates especially, once again, around environmental issues – see for example the letters from climate scientists on the website isthishowyoufeel.com. Veteran climate scientist James Hansen once confessed to feeling like he was screaming at people from behind a soundproof glass wall.

I don’t disagree. To me, science can seem wildly popular, at least from the evidence of the websites and documentaries dedicated to it – but I also know that the opposite is true. I understand that there is resistance and scepticism about science: among the 13% of New Zealanders who are sceptical about climate change (according to media reports of a 2015 study); or the ‘alternative’ communities who are resistant to vaccination. I don’t generally share this scepticism, and nor do I pretend that I can intuit the reasons for it. But here, perhaps, is science against the people.

Of course there is no people. There is no public as a whole, any more than there is science as a whole. The climate sceptics are largely conservative, white men, and hardly represent the majority of the population. If some people are resistant to some science, or to the word ‘science,’ or to the personalities of some scientists, then there are no doubt a hundred reasons why, some conscious and some not. But politics, writing and science are useful headings to map out some of the sources of resistance. Science tells us the way the world is. At its best – in those moments of genuine ‘citizen science’ – science involves us in its work, inviting us to join its communities of agreement. When science is frustrated, it is frustrated because of the perceived unreasonableness of people who don’t share its perspectives or appreciate its results.

There can be no agreement, no sharing of knowledge and perspectives, not when half of us exploit the other half and the earth.

And politics has a response to science and its frustrations: we will not be reasonable. We will form unions and parties, organise marches, and take sides. There can be no agreement, no sharing of knowledge and perspectives, not when half of us exploit the other half and the earth. No matter what the world is like, no matter how much evidence we present for the scientific facts, people still don’t have to accept them. Writing, too, has an answer: we can talk and investigate and share knowledge, but we can never feel one another’s pain. Without writing – without expansive thought – we may have no reason to bother with science or politics, with knowledge or with action.

So I don’t want to assume that I know the answers, but I am guessing that alongside all the other problems – the appearance of the scientific establishment as a comfortable and distant elite, say – science becomes unpopular when it forgets that there are other things to think about, and other ways to think them.

This essay isn’t about a marshalling of the ranks against science. Science is my background, and in many ways it still colours my world. I do love science, even if I don’t love the websites that love science. As a teenager I had a lot of science books, including some of the large format Scientific American subject compilations – one about cosmology (with an additional chapter on the search for extraterrestrial intelligence), one about the earth sciences I think, and maybe one about mathematics too. I first read about the possibility of global warming in, presumably, yet another one. I remember the worlds and the excitement of those books – their images, their graphs and diagrams, the gloss of their paper and their black dog-eared covers. I come from a science family – not only in that my father and brother are both scientists, but also, I think, in that the kind and collegial ethos I’ve been talking about largely predominates among us. In the context of my family, it’s not something I would dream of changing or challenging.

And then step outside of that, and the world seems different. I don’t know what happens to reason and reasonableness once the pain and fury and exploitation of the world loom into view. I don’t think reasonableness – mine or others’ – has any kind of answer to them. We can’t wish it all away with hopes for rationality and evidence. A march for science? Well, I went along. The speeches took place in the small amphitheatre outside Te Papa. It was a good spot, sheltered and enclosed by the tiers of seats and the bulk of the building itself. It felt small and walled in. Outside was the city and the harbour, and, and. And beyond.

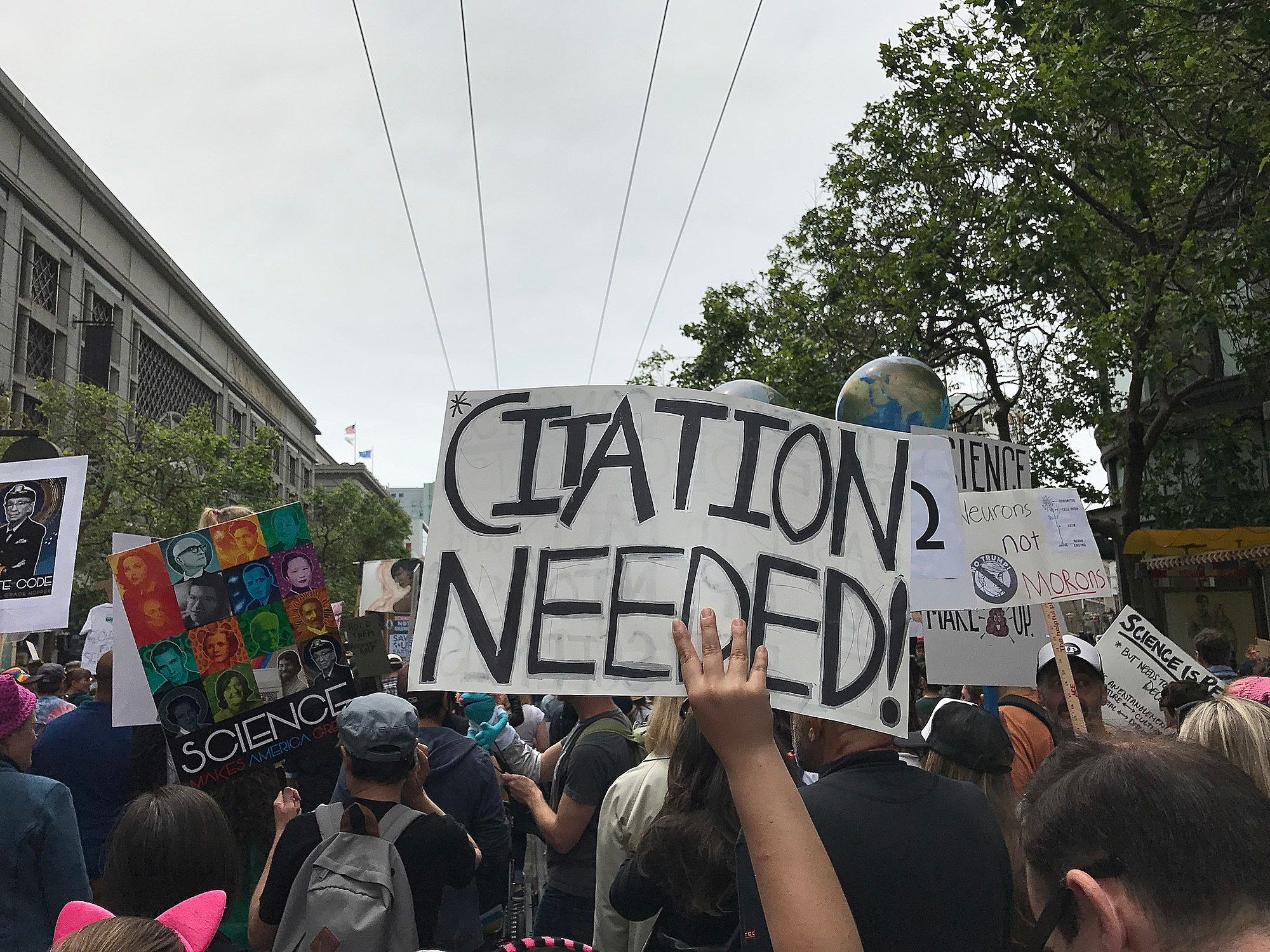

Feature Image: March for Science in San Francisco, California, April 2017, by DarTar. Used under Creative Commons.