Refining Abundance: Considering Queer Algorithms

Queer representation is vital in visual arts. But are group shows the answer? Francis McWhannell discusses different possibilities in this response to the latest exhibition at Gus Fisher Gallery.

I recline on pieces of a knobbly kind of foam I think is used to soften ambient noise in recording studios. Beneath me is an expanse of printed water, doubled like a Rorschach blot. It flies up at my feet, begins to curl, and dissolves overhead into a sheet of balloons, evocative of both sea spume and an end-of-night balloon drop in a club. A few of the globes are puckering. It’s May, and the party has been going since the end of February, a long time for even the most high-spec of balloons. I’m enveloped, physically and aurally. A polyphony issues from speakers arrayed around the perimeter of the installation: the gurgle of water; the chirrup of birds; a call to prayer; plunking dance and dreamy new-age music; chants and monologues and recitations by the artist; words of affirmation and instruction; sounds of breathing.

The work, Ritual Without Belief (2018), is by Evan Ifekoya (born in Nigeria, based in the United Kingdom). It is, in several senses, central to the group exhibition Queer Algorithms at the University of Auckland’s Gus Fisher Gallery. The installation literally occupies the gallery’s heart, its grand foyer. It also relates to the show title. Ifekoya has likened the process of sifting and organising their mass of sonic material to an algorithm, which term has been adapted by curator Lisa Beauchamp. In the wondrously wonky exhibition leaflet, designed by Gabi Lardies, Beauchamp notes that the artists included “are reconfiguring new algorithms for change against continued systems of exclusion”. She further makes reference to Ifekoya’s work in describing the show as a place of abundance.

I understand the reasoning behind this choice of framing. It resists the notion that LGBTQIA+ marginalisation and struggle are automatically attended by impoverished experiences. It reiterates the fact that queerness is hyperactively plural, subsuming the same socio-cultural texture that is found in the straight and cisgender mainstream, plus a whole lot of texture that isn’t. The show is unquestionably profuse. It features a dozen artists or groups, both local and international. Some are represented by a single work, others by several. The larger of the Gus’s two galleries is filled with pieces by self-declared maximalist John Walter (United Kingdom): two films, three costumes, two huge paintings, an artist’s book. The exhibition pulses with colour, movement, and especially noise. The overall tone is celebratory – very much in line with the Auckland Pride festival, with which the show was originally connected. The aim: to treat audiences to a richly queer space.

Another objective is more critical. Beauchamp notes, “The timely nature of this exhibition cannot be overstated with a severe lack of programming of major group exhibitions by queer artists in Aotearoa’s public art galleries.” Reading the comment gives me pause. This specific lack has never really occurred to me, despite the fact that I’m queer (that is, a gay Pākehā who has never much liked the gender binary but ticks ‘male’ on forms), and a dedicated gallery-goer who tries to keep up to date with what’s going on in our major centres at least. Some of my favourite group shows of the past few years have been queer-centric, most notably Sleeping Arrangements (2018), curated by Simon Gennard for the Dowse Art Museum in Te Awakairangi. I’ve strong memories of the tenure of Misal Adnan Yıldız, director of Artspace Aotearoa in Tāmaki Makaurau from 2015 to 2017, who oversaw the production of a number of multi-artist exhibitions that centred queerness.

Evan Ifekoya, The Gender Song, 2014. Photography by Sam Hartnett.

Bronte Perry, filthy angry faggots, (detail) 2019-20. Photography by Sam Hartnett.

Then, too, I’ve never really thought of major group shows as especially vital where LGBTQIA+ representation is concerned. Solos and other tighter presentations strike me as inherently more valuable, since they afford artists greater prominence and agency, leaving it up to them to do whatever feels most urgent. Three of last year’s finest exhibitions were solo or collaborative projects by queer artists: Fiona Clark’s Raw Material at the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery in Taranaki, Owen Connor’s SISSYMANCY! (2019) at play_station in Te Whanganui-a-Tara, and Areez Katki’s Some Retained Delights at RM Gallery in Tāmaki Makaurau. Queer Pacific collective FAFSWAG and its member artists have shown or performed at various public institutions in recent years. Founding member Pati Solomona Tyrell was even a finalist in The 9th Walters Prize (2018). Oracles, which has just opened at City Gallery Wellington Te Whare Toi, sees him paired with Christian Thompson, a queer artist of Aboriginal heritage.

However, I must concede that I falter rather when I think of some of our ‘premier’ institutions: Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū and the Dunedin Public Art Gallery. All, of course, show queer artists and treat queer themes. Toi o Tāmaki – which hosts the Walters Prize, although it does not select the finalists – is currently displaying early photographs by Tyrell as part of the long-term collection exhibition Seeing Moana Oceania (2018–20). Te Papa’s Kaleidoscope: Abstract Aotearoa (2018–present) includes work by well-known lesbian artist Lonnie Hutchinson, who also has a large piece, Hoa Kōhine (Girlfriend) (2018), installed on the outside of Te Puna o Waiwhetū.

Dunedin is perhaps the most proactive of the bunch. Its Rear Window video space has featured several queer works in recent years, including Tyrell’s Fāgogo (2016), which was shown in 2018 in collaboration with Blue Oyster Art Project Space. Last year, the gallery’s Curatorial Intern, Milly Mitchell-Anyon, presented Patrick Pound’s Summer Holiday 1962 (1986) in the Rear Window. She also curated an exhibition of work by Aotearoa women artists of the late 19th to mid 20th centuries, The Circle (2019–20), which touched on questions of queerness. LGBTQIA+ content is in the mix. And yet I can think of no substantial show – group or solo – mounted by any of the ‘big four’ of late that has focused squarely on queerness. A lack can be discerned.

*

The idea that there is ‘room for improvement’ vis-à-vis queer representation at some of our major art institutions has recently been doing the rounds. In April, The Spinoff published an article on the matter by Samuel Te Kani, which responded, in part, to a Tumblr post by artist Daniel John Corbett Sanders. In the piece, Te Kani made mention of Queer Algorithms, suggesting that the show, and others like it, might usefully serve to shuttle “works and artists from more queer-centric artist-run spaces to larger galleries like Auckland Art Gallery”. Such shuttling is an expected function of exhibitions at institutions like the Gus. Few artists turn up at the bigger galleries without passing through the mid-sized ones, and it is nice to imagine that Queer Algorithms might help to highlight and promote the local artists it features. At the same time, the show seems to me to have another function, not to say ambition: modelling the sort of queer exhibition that one might expect to be mounted by a major New Zealand gallery.

I can well imagine Queer Algorithms being staged at the Gus’s nearest big brother, Toi o Tāmaki. It might even work well at that institution, with its voluminous spaces and its, at least theoretically, broad audience. Of course, any big show devoted to queerness – rather than just including artists addressing queer questions – could easily be side-stepped by more conservative visitors. But the inevitable banners and billboards, and light-up bus-stop ads, and promotional matter within the gallery itself would at least signal a position. Some LGBTQIA+ visitors to Toi o Tāmaki might appreciate having a show all their own in the hallowed halls, particularly if it were integrated into the everyday programming, rather than associated with, and enabled or justified by, Pride.

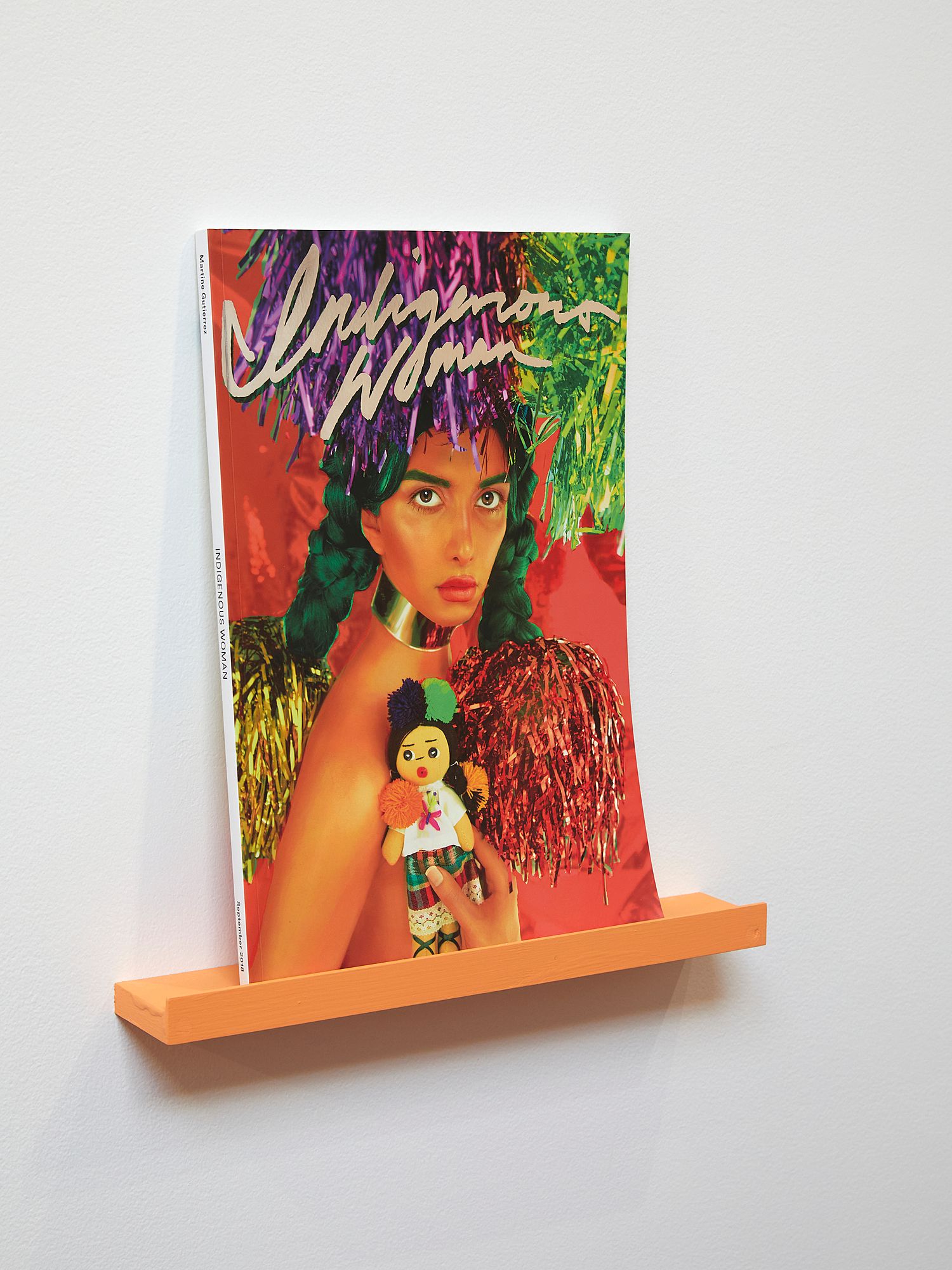

Queer Algorithms at the Gus is a harder sell. The solidarity value remains, irrespective of the logically smaller reach of the gallery (not many members of the general public are stumbling upon this show, I’ll be bound). But the exhibition sits awkwardly. Works are compromised. Some are crammed into inferior spaces. Others fight to be heard and seen in a busy environment. Martine Gutierrez (United States) – who is a big name overseas but has not, to my knowledge, been shown here before – is especially hard done by. She is represented by two works: the music-video-like Clubbing (2012); and a publication, Indigenous Woman (2018), which burlesques fashion magazines in general and Andy Warhol’s Interview in particular. In both cases, the artist is the sole cast member, or the sole living cast member; the magazine also features mannequins.

Martine Gutierrez, Indigenous Woman, 2018. Photography by Sam Hartnett.

The works are marvellous: witty, engrossing, abundant in their own right. But they’re not well served by the show. Clubbing is presented in a crummy downstairs space. Indigenous Woman is easy to miss, since it is displayed on a shelf on its own, rather than in quantity or alongside photographic prints, as it has been in other contexts. Gutierrez gets lost. She wants more space, and warrants it. And she isn’t alone. The root problem is that the quantity of content in Queer Algorithms is off. The exhibition doesn’t communicate glorious flamboyance so much as overkill. It is quite impossible to properly experience a complex installation, an interactive website, and seven videos (some, admittedly, are more minor) in one go – let alone those works plus a bunch more. One is compelled either to make repeat visits or to pass over bits that don’t quickly appeal. In a not-very-big gallery, that seems unnecessary.

Overloaded exhibitions are not exceptional in Aotearoa at present. As Lucinda Bennett recently pointed out, it’s become rather common for public galleries to emphasise the “biennial-style group show”: broad concept, array of artists, daunting whole. The Gus itself has shown a preference for such exhibitions of late. So has Auckland University of Technology’s ST PAUL St Gallery, which last year decided to radically scale back its programme. Its motivation – to curb burnout in the face of limited staff numbers – was admirable, but there was a major downside. The gallery effectively committed itself to running baroque group exhibitions, and precluded the possibility of the gemlike solo. Artists and audiences are suffering.

The problem is compounded by the model that tends to underpin the galleries at the top of the pecking order. Here, too, group shows are common. Solos are limited in number, and as likely as not go to already well-known artists. Run times are long. Loan shows are typically up for months. Collection shows can last years. The notion that Queer Algorithms might act as a shuttle is, on closer consideration, kind of dubious – and especially where Toi o Tāmaki is concerned. While works from the less-than-thrilling collection of historical international art constantly occupy the enormous Mackelvie Gallery, no room is permanently given over to short-term exhibitions by living local artists. The probability of any such artist getting shown in general is low, unless they happen to be nominated for the biennial Walters Prize, included in one of the semi-regular Chartwell Shows, or make it big overseas.

It strikes me that the Gus is modelling the wrong kind of exhibition with Queer Algorithms, or directing itself towards a less urgent lack than it otherwise might. I’d sooner see more substantial shows by individual queer artists in our public institutions than yet more group affairs. It bewilders me that Ōtautahi-based Paul Johns, a pioneer of queer art in New Zealand, has had no solo exhibition in Tāmaki Makaurau in recent years. It saddens me to think that many of our most dedicated younger queer artists – some of whom are already present in Queer Algorithms – are unlikely to have the chance to flex their muscles in a major public gallery that offers space, funds, and expert support any time soon. But mid-sized galleries can come to the rescue.

*

Within the panoply of Queer Algorithms, I return again and again to two local artists: Bronte Perry (Ngāpuhi, Pākehā) and Aliyah Winter. They’ve had shows of their own, in smaller spaces outside Tāmaki Makaurau. Ōtepoti residents can currently see a video work by Winter and takatāpui artist Nathaniel Gordon-Stables in the Dunedin Public Art Gallery’s Rear Window. Winter’s presence at the Gus is relatively slight. An untitled series of decals scattered about the gallery makes subtle reference to stickers disseminated by transphobic, or transmisogynist, groups. They are printed with images of the artist’s face, contorted as if mashed up against the glass of a photocopier, or perhaps slammed into a door by some unseen aggressor. They are organic in shape, like overinflated Ys. I read them immediately as cocks and balls, and Winter has called them phallic, but they’re legible in other ways as well: chromosomal, fluid-like. They’re poetically polyvalent.

The root problem is that the quantity of content in Queer Algorithms is off.

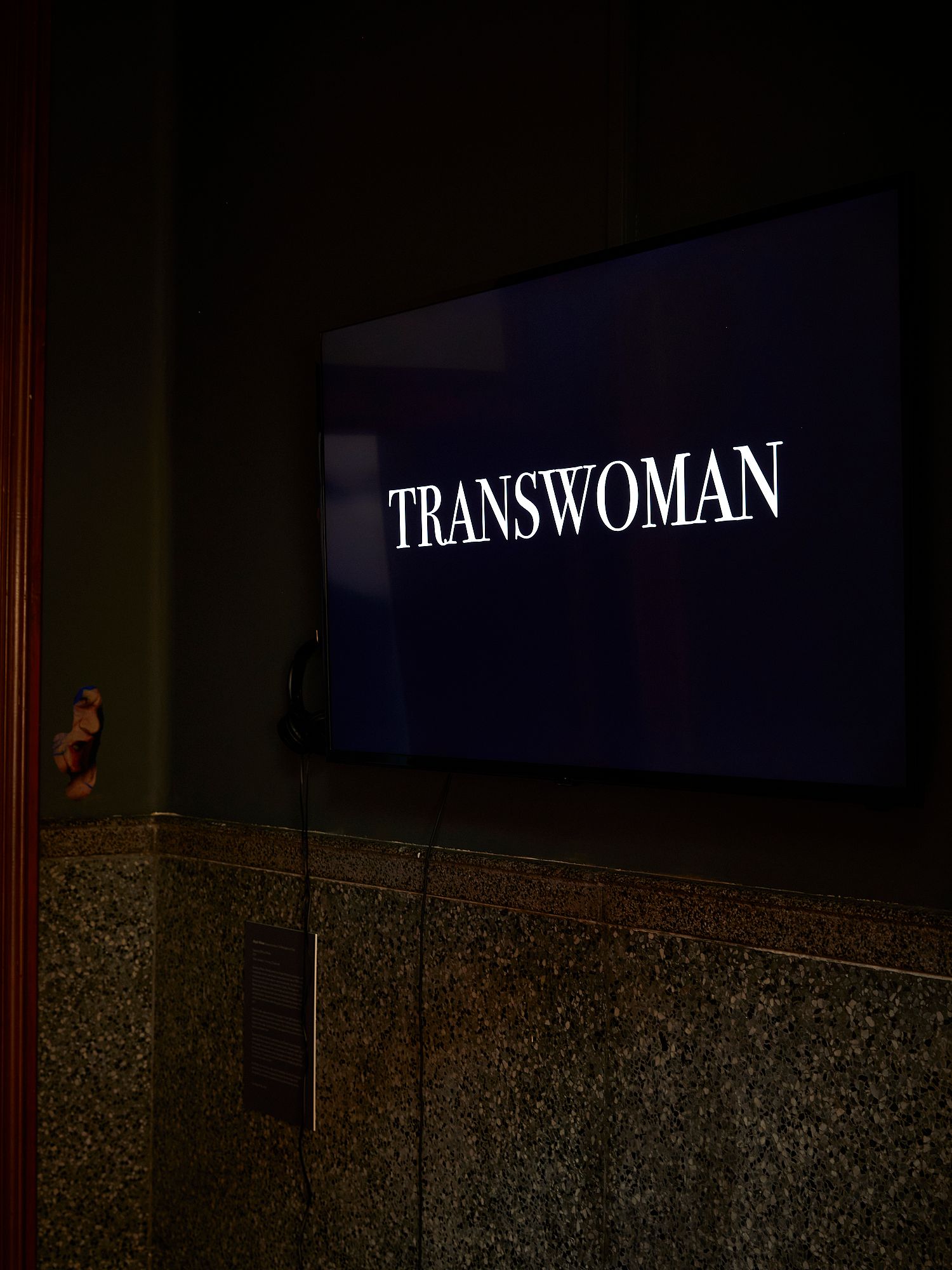

So, too, is Winter’s other contribution, Speaking without words (2019), a short video that loops perpetually on a small screen in a tight anteroom. The work centres on text, adapting phrases from anti- and pro-trans sources alike. Capitalised expressions flash on screen, white on black. The typeface is, I think, Bodoni, a glossy-magazine favourite and ever a little dazzling, tricky to read quickly. ‘WOMYN’ and ‘WOMXN’, feminist variations on the word ‘women’, appear prominently (the latter is expressly intended to include non-cis-gender women). The embedded X and Y remind me of the human sex chromosomes, as well as placeholders with infinite potential referents in logic or mathematics. Winter modifies the spellings of other words, riffing on the archaic-cum-internet language of poet Jos Charles. ‘Brave’, for instance, becomes the Eve-marked ‘BRAEVE’. A computerised voice, gender indeterminate, effortlessly recites the terms, emphasising the notion that sense-making precedes normalisation.

The artist plays with ambiguity and slippage. The utterance “There is a space between trans and woman,” which makes reference to Jay Hulme’s ‘A War in Words’ (2019), points to the importance of separating the words ‘trans’ and ‘woman’, instead of running them together as ‘transwoman’ – an expression that is sometimes employed by anti-trans individuals, and that wrongly positions trans women as other than women. The subsequent utterance “There is no space between trans and woman” at once describes the error and underscores the fundamental union of women and trans women. The digital voice reorients terms that would seek to injure trans people. ‘SHEMALE’ is consistently pronounced ‘female’.

Two sentences in Winter’s video are spoken aloud without text to accompany them onscreen: “If you have to shout to be heard you are heard as shouting. If you have to shout to be heard you are not heard.” Lifted from the lecture ‘Snap!’ (2017), by Sara Ahmed, the quotation gets at the idea that when one protests one is immediately vulnerable to charges of anger and overreaction (the misogynist term ‘hysteria’ comes to mind), as well as the problem of being relentlessly ignored. Today, in June, I can’t help but associate these sentences with the present protest actions across the world, in the aftermath of the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis at the hands of the police.

Aliyah Winter, Speaking Without Words, 2019. Photography by Sam Hartnett.

Aliyah Winter, Artist-made Stickers, 2019. Photography by Sam Hartnett.

Martine Gutierrez, Clubbing, 2012. Photography by Sam Hartnett.

Of course, their relevance was no less last month and in New Zealand, which is hardly low on injustice. We have anti-trans groups, as Winter’s stickers acknowledge; we have police misconduct, and awful inequities within the so-called justice system: both of which disproportionately affect trans people and people of colour within the queer community. These realities famously folded into Auckland Pride’s decision to prohibit police from marching in uniform in the Ponsonby parade planned for 2019 (they were welcome to participate in other attire) and, later, to reimagine the parade as a march through the central city, echoing the first Gay Liberation protest in 1972.

Perry makes direct reference to the relationship between queer people and the police. They present a series of PVC banners in the rear stairwell of the Gus. One is an image of two officers pashing in bullet-proof vests that call to my mind the recent stationing of Armed Response Teams in South Auckland, Waikato and Canterbury (the project has since been abandoned). Rainbow and New Zealand flags skin the heads of the figures, and the missile-like forms that surround them. Perry calls for queer radicalism, not tameness, noting in their artist statement, “I want a filthy angry faggots liberation that lies in the obscenity of their luv, their rage, their vulgarity.” Probably not Auckland Art Gallery’s cuppa, but-and-therefore particularly urgent.

Perry’s work, like that of Winter and Gutierrez, represents a compelling core within the mass of Queer Algorithms. Alas, the mass buries these artists, and convolutes the already complex stories they’re trying to tell. I find myself compulsively doing what you’re not supposed to do as a critic. I mentally reimagine Queer Algorithms instead of contending with the given. I want to trim the show back. Give Perry the entire central space, perhaps. Give Winter the smaller of the two flanking galleries, a whole wall for a screen, if she’d like it. Give Gutierrez the larger space. One group show becomes three solo shows, interrelated. No one is required to shout to be heard. They shout only if they want to.

The Aotearoa art scene in general is a place of abundance, yielding a large number of exhibitions, texts and public-programme events (probably too many of those, in fact), as well as an ever-increasing quantity of ‘online content’. What tends to be missing from the mix is sifting, refinement. Very often, the most exciting shows in the public-gallery space come out of the smallest and most cash-strapped of institutions: taut solo or otherwise artist-led exhibitions that – to paraphrase an artist friend of mine – help one view and navigate the world in a different way. We could do with more such shows in galleries like the Gus, which have more in the way of resourcing and room. Shows that are well formed and well paced, compact but not squeezed. Shows that empower artists, trusting them to bring depth and texture, and to speak to broad audiences. Shows that demonstrate, rather than declare, what they value.

Gus Fisher Gallery

19 May 2020 – 27 Jun 2020

Feature image: Queer Algorithms, Installation View. Photography by Sam Hartnett.

This piece is presented as part of a partnership with Gus Fisher Gallery, which covers the costs of paying our writers while we retain all editorial control.