Survival Tactics: A Review of WEiRdO

Matt Loveranes reviews Waylon Edwards, Jane Yonge and William Duignan's strange, surreal WEiRdO, a comedy about a finding your identity in a Pākehā world that would rather you didn't.

Matt Loveranes reviews Waylon Edwards, Jane Yonge and William Duignan's strange, surreal WEiRdO, a comedy about a finding your identity in a Pākehā world that would rather you didn't.

Note: this review contains some spoilers for the second half of WEiRdO.

WEiRdO derives its name from two words: wero, the Te Reo word for challenge and ID, shorthand for identification. In an increasingly ideologically polarised world, how you look and identify can be the difference between living your life normally or living it like a horror movie: the deck is stacked against you, every move feels like the wrong one, and ultimately, you can’t win, let alone survive. As conceived by Waylon Edwards (Māori) William Duignan (Pākehā) and director Jane Yonge (Chinese-New Zealander with roots in Fiji), WEiRdO issues a challenge on how we view race in New Zealand. Although it zeroes in on the racial aggression and ignorant attitudes primarily fostered by Pakeha, the main benefactors of social and economic privilege, the challenge resonates for everyone, regardless of skin colour and cultural background. It holds up a mirror for us to see our own faults, our own biases, and our own horrific behaviour.

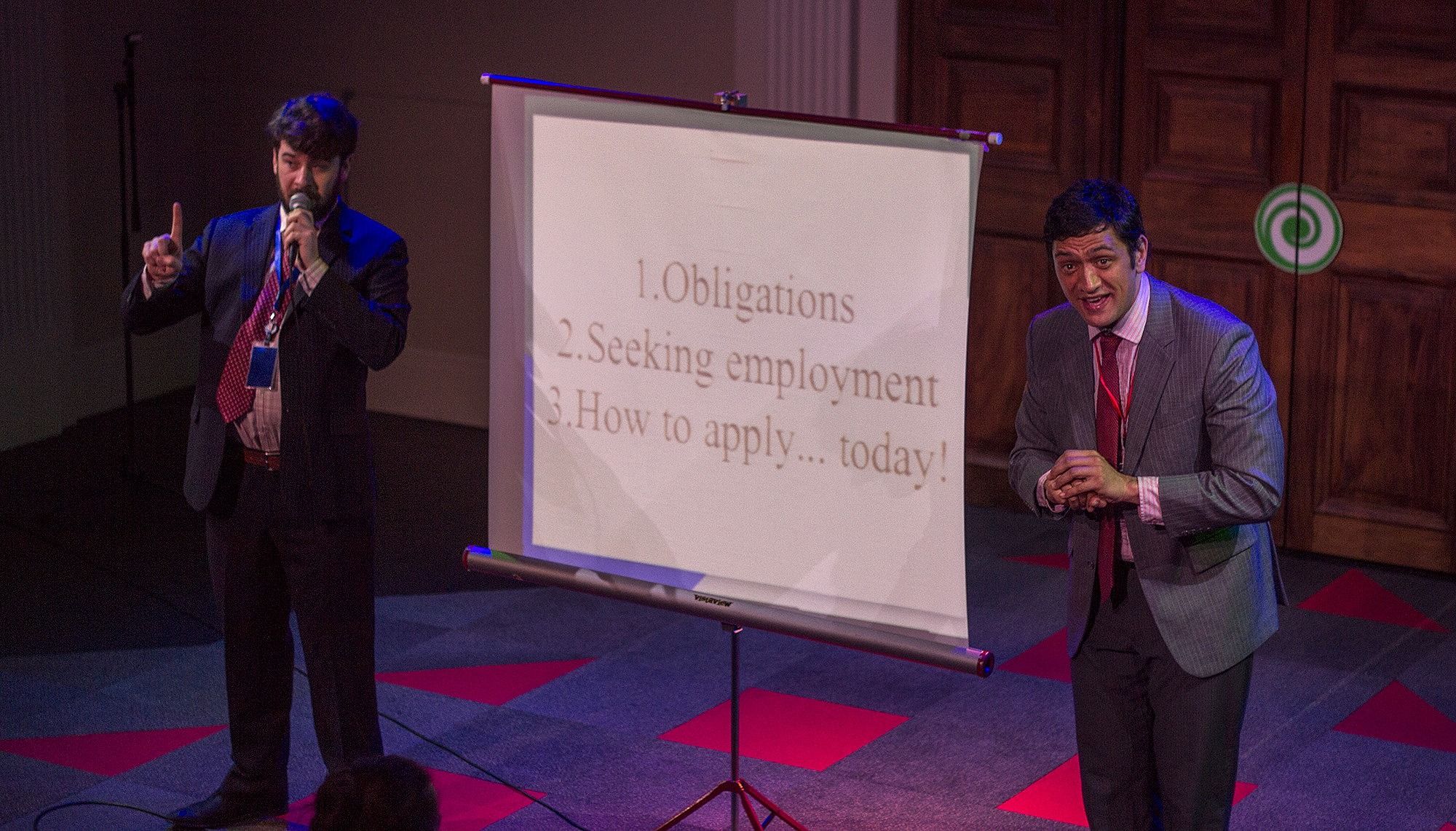

Richard (Duignan) and Waylon (Edwards) gregariously welcome us to the cheekily-named Department of Lifestyle Encouragement, but their greetings are eerie and artificial. They’re here to give a presentation on the benefits of having a job and how easy it is to get one. But with frozen smiles and unblinking eyes, they’re two Madame Tussaud’s figures, marching towards us to techno-fied Gregorian chants. It’s some straight-up Black Mirror shit: Richard’s a used car salesman, spouting out empty statistics and client obligations and his bullshit is propped up by Waylon, hunched-over and subservient. The perfect Igor to his Dr. Frankenstein. The routine is funny but terrifying. It gets to the core of the machinations behind our social development system and how ridiculous and inhumane they can be.

Just as we settle into this heightened horror-show, Edwards and Duignan peel back the creepiness, turning focus to the minutiae of Waylon’s work life and the real horrors he has to face every day.

Waylon’s “a gentleman, sensitive, well-spoken”. He shows up on time, although Richard remarks he could come earlier (6am earlier). He never puts a step wrong and works twice as hard to get the same recognition as his Pākehā colleagues. He’s the epitome of a model minority.

Richard, all cheek and bravado, splays his legs across Waylon’s desk, literally, a white man invading his space. He aspires to jumping rank and getting the exclusive gold lanyard, which puts his blue lanyard - and Waylon’s lower red lanyard - to shame. But it’s Waylon who’s been putting in the work for promotion, denying a recently released mother her benefit because she didn’t keep her receipts and getting an aunty investigated for benefit fraud because the kids she’s looking after aren’t hers. The koru behind him now looks more like a hypnotic swirl. Waylon’s been brainwashed, using his position to deny help to those that need it most. It’s a sharp and cynical dig at the system: in order for him to survive it, he has to lose a bit of his humanity.

Inside the package is the ultimate fuck you: a gold lanyard. Waylon’s gold lanyard. Richard tries to congratulate him, but his unwavering belief in his God-given privilege quickly spills out: “You got the job because you’re Māori. It’s good to have a bloke like you on top. It’s good for business.”

It’s these little niggles that WEiRdO gets right. Every person of colour is built with an internal GPS system to navigate everyday compromises and microaggressions. When an “ethnic looking” delivery person (Yonge) comes to drop off a package, Richard immediately asks her the dreaded question: “Where are you from?” I groan. “Wellington,” she responds in earnest. He prods her further, “Where are you really from?” “Auckland,” she hits back, harder this time. Each time she sticks it to the man, however small, is a reclamation of power.

Inside the package is the ultimate fuck you: a gold lanyard. Waylon’s gold lanyard. Richard tries to congratulate him, but his unwavering belief in his God-given privilege quickly spills out: “You got the job because you’re Māori. It’s good to have a bloke like you on top. It’s good for business.” Waylon’s stunned into an intense silence. Richard’s conjured up the overriding fear that every person of colour secretly harbours: that no matter how much you achieve or how high you fly, you might never get the job or earn the accolade on your own merit. There’s always a Richard to discredit it. You’ll never be good enough.

That’s when Waylon’s ghosts come back to haunt him, Māori voices that come from above (or from within). They enlighten him to his own shortcomings, his lack of fight, his lack of identity. So, when Richard needles him for a karakia to ‘celebrate’ his promotion, the burden is two-fold. It’s on Richard for assuming that Waylon would know one just because of his heritage, but it’s also on Waylon, whose lack of connection and inability to take pride in his cultural identity prevents him from fighting back against the inhumanity and oppression levelled by the Richards of the world. He’s useless to change other peoples’ lives for the better, let alone his own.

WEiRdO wears this droll, off-beat irony like a badge of honour and it’s thoroughly modern and refreshing as a result. Even its production design winks at us. The office space imagined by Emily Hartley-Skudder, is both familiar and isolating. The modular carpet tiling lining the floor may be generic and boring, but it’s also comforting. Waylon’s computer monitor, big and old, is a fossil suggesting the slow progress not just of technology but of society as a whole.

This whimsy and playfulness is also palpable in the performances. Despite playing a literal Dick, Duignan’s roguish charm floats to the surface. It’s in his confident gait, the over-exuberance in his voice and his willingness to push each joke just that little bit further, maybe with a weird tic or line delivery, that makes him a compulsively watchable cartoon villain. Edwards gets the more emotionally complex showcase. Every gesture is laced with an undercurrent of insecurity and in the moments where he drops his pretences, like his shell-shock at how Richard reacts to his promotion, he’s truly heart-breaking.

WEiRdO begins with its most unreal moment but concludes with realness. The fictional universe is dismantled and the actors address the audience as themselves. The woke Duignan talks over Edwards, attempting to differentiate himself from Richard, but he’s literally pushed out of the room and silenced. It’s Edwards’ turn to speak. Edwards addresses us in Te Reo. He speaks delicately and deliberately, his voice breaking in his most personal statements. He speaks until he stumbles, but even if he loses his words, he regains his power and his identity. His anger isn’t an avalanche trapping everybody in the muck we’ve created. He appeals to the heart instead, inspiring us to fix our shortcomings by fixing his own before us. He can’t erase who he is; by embracing a part of himself he’s denied for so long, he’s a weirdo no more. It’s the yin to James Nokise’s powerful galvanizing yang of a coda in Rukahu and the emotional effect is just as seismic.

WEiRdO isn’t seamless. It’s a stitched-up Frankenstein’s monster that’s part-high concept horror, part-workplace satire and part-metatheatre. Yet despite its disparate parts, it throws a powerful gauntlet. For me, it’s most significant that it was made by three people of different cultural backgrounds, with their own personal cultural baggage and bias. Through their shared vision, they’ve made something that helps the Waylons of the world feel less scared, less different, less alone. If the fictional version of this story had continued, I’d like to think the newly-awakened Waylon would now boost his underprivileged brothers and sisters up. But as long as there are Richards in the world, the lives of the oppressed and the downtrodden continue to be horrific. Not all of us are Waylons, but we all have the capacity to be Richards. Minorities alone shouldn’t be the only ones pulling our brethren up, nor should we be pushing them down. This burden is everyone’s. If we help each other be less like monsters, perhaps we all survive to the end.

WEiRdO runs from 31 October to 4 November at BATS Theatre.

Tickets available here.