The Beautiful World: A Review of Some Things to Place in a Coffin

Helen Lehndorf spends some time with Bill Manhire's latest collection and finds a work that is philosophical, funny, and haunting.

Helen Lehndorf spends some time with Bill Manhire's latest collection and finds a work that is philosophical, funny, and haunting.

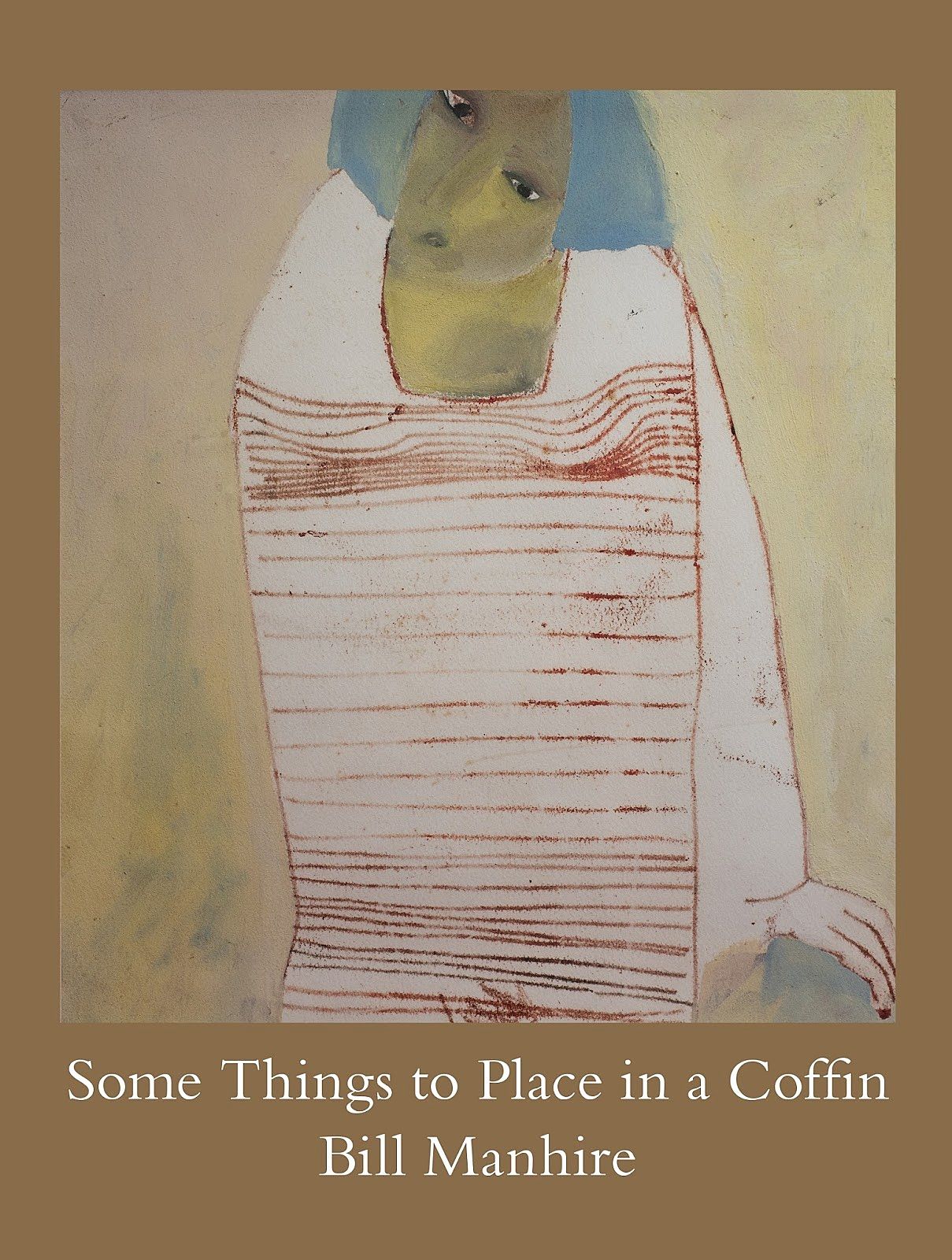

When a poet is as fine as Bill Manhire, seven years can feel like a long wait for a new collection. However, on reading Some Things to Place in a Coffin I appreciated the time he has taken to construct this beautiful and considered book – work of this quality doesn’t happen in a hurry. The cover has a delicious ‘old-gold’ metallic hue, as though the book itself could be an appropriate offering, as per the book’s title.

The book opens with a haiku, ‘How Memory Works.’ Haiku are usually the one-grab image, the polaroid photograph of poetry, yet Manhire in his inimitable way has written one with an expansive poignancy; seventeen syllables which immediately pierce the heart, creating a sense of shifting time, dislocation, and unsteady ground:

Come over here

we say to the days that disappear.

No, over here.

In an interview with his publishers, Manhire said, ‘I like readers to feel secure and insecure at the same time.’ This aptly describes the experience of reading this book: there is the both a sense of having no idea what might be met within each new poem – it might be about any time, any terrain, from any voice – and yet there is a sense of trust, too, that you are in good hands. Manhire’s poetic voice is always at an artful distance, and the work is not confessional. Any sense of intimacy comes more from a wider shared human experience rather than his personal, revealed experience.

Manhire’s poetic voice is always at an artful distance, and the work is not confessional. Any sense of intimacy comes more from a wider shared human experience rather than his personal, revealed experience.

One of the main things any poet hopes for is to continue to grow the scope of their work, and to have the writing be surprising and fresh, to avoid ruts, and ditches and dead-ends. This is where Manhire demonstrates virtuosity: his work is so cleverly constrained, and his subject matter continuously fresh and unpredictable. What catches his eye is artfully random. Several times in my reading of the book, I couldn’t discern quite what he was conveying, and yet it also didn’t matter to me. After a bit of scratching around in my mind, I was content to let the images be the images without needing to attach certainty to them.

In ‘Waiting’ he conveys our humble human hope for peaceful continuity with, ‘The day hopes to be successful / a prose day really, nothing untoward,…’ Playing on ‘prosaic,’ here, the image captures a shared desire for our lives to carry on with ‘no alarms and no surprises’ as Radiohead phrases it.

These poems seem to belong to the world, they roam and drift. It is not a collection particularly anchored in New Zealand (although the soldiers in ‘Known Unto God’ refer to New Zealand). There is a wry humour which appears always at the right time, leavening poems just when they could use it. In ‘Election Address’ the voice of the poem declares ‘I license the poets you hope to score beneath,’ and the multiple meanings in this line are funny and pointed. In ‘The Poet’ he writes: ‘There is nothing / new under the sun, yet this is where / my best ideas come from.’ Manhire refuses to settle on absolutes (because where is the fun in that?): ‘Of course I don’t actually believe in ghosts / but this one seemed legitimate and spooky’ he writes in ‘28 Stanzas in the Haunted House.’

The ‘Known Unto God’ series, written as a commission as part of the commemoration of the Battle of the Somme, is separated from the rest of the collection with black and grey end-papers, which is effective in delineating the poems and has the effect of a visual altar cloth; the dark end-papers suggest a kind of protection or shroud around this series. Manhire has said that these poems represent the voices of imaginary dead soldiers. They are haunting and true, and the fleeting images and randomness captures the roaming and arbitrary machinations of the human mind under duress.

‘I keep trying to remember’ says the voice of ‘The Question Poem.’ This attempt to remember, the reach towards elusive memories is returned to throughout the book. A longer poem ‘What Will Last’ is both funny and sad as the narrator clings to a failing memory and tries to make sense of a disorientating world. Failure of memory, and ultimately, whether it matters is a repeated trope through the poems, as well as the shortfalls of language. Ironically, here is a poet exploring how much of our human experience is beyond words and utterly inexpressible. He attempts to express this very quality of how words fail us in ‘Learning’: ‘For a moment the raft / is reachable, then it isn’t.’ This is a philosophical book, in the sense it asks questions but does not need answers: ‘You cannot reach the beautiful world’ he writes in ‘The Beautiful World.’ The questions are where the wisdom of the work lies.

The collection has a tone of time passing, memory, of waiting, of inevitable endings, illustrated by this moving final couplet from ‘The Enemy’: ’And soon enough it will be gone / this world you once woke into.’ This is a haunting, controlled and beautiful collection, with much to offer: humour, light-handed contemplation …and even solace.

Photo Credit: Image of Bill Mahire by Grant Maiden.