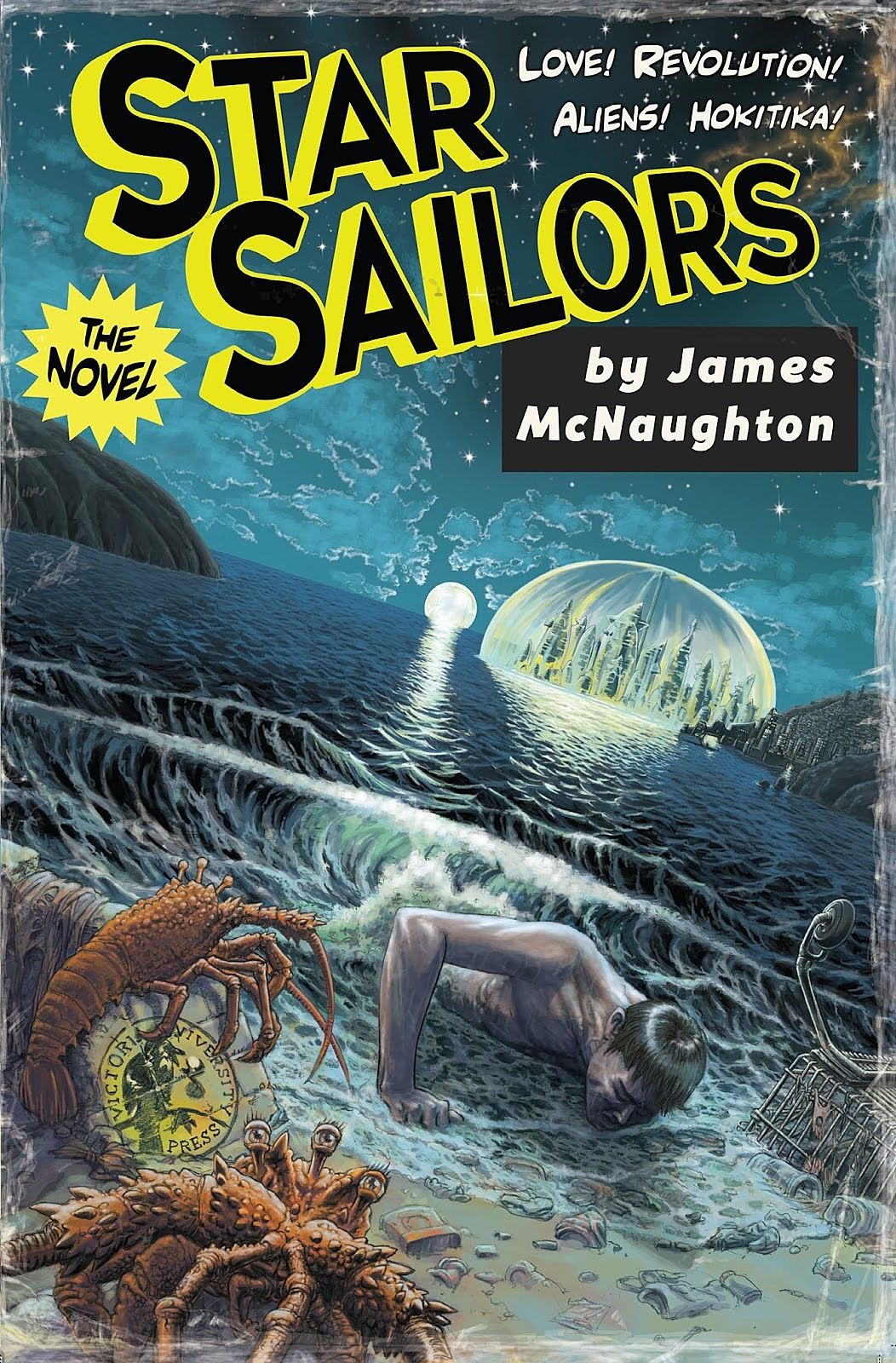

Spec-Fic Month: An Excerpt from Star Sailors

Read an excerpt from James McNaughton's new novel, Star Sailors.

The following prologue is from James McNaughton's new cli-fi novel, Star Sailors. You can read our conversation with James McNaughton and Darian Smith about speculative fiction, magic systems, and the genre vs. literature divide.

Prologue

23 August 2045

The sun came out and shone on the aspirational suburbs of Wellington’s south coast. Houses dug in to hillsides, perched along ridges and on clifftops gleamed; solar panels lit up on roofs along the valley floors. A few schools had closed for a day due to flooding, but the storm hadn’t been so bad. Roofs had stayed on, pumps pumped and drains coped, for the most part. The seawall had held.

Mini turbines cut in and whirled like propellers. So many of them it seemed the hills might lift off. The flurry died away. Stillness reigned. Windows were flung open, washing hung out, children let loose. Steam rose. Drones attended to houses as if they were flowers.

Turbines wheeled into motion again. Doors slammed. Scraps of cloud sailed overhead, driven from the north this time. Another gale was brewing already. The big swell running in from the south gathered in size as it reached the coast. Waves lofted, held up by the strengthening wind. Their tops curled, shed blasts of white spray and avalanched. Seawater rushed, hustled and excavated.

Freedom’s Rampart retained full structural integrity, according to internal sensors. Built in 2026 to last one hundred years, the seawall wound along the rocky coast from Öwhiro Bay to Moa Point, along the seaward side of the old two-way south coast road, soaring like a castle battlement above the mutinous ocean. The highest and thickest seawall in greater Wellington’s coastal and harbour network, and the most wave-battered and photogenic in New Zealand, it rose to a mighty eight metres in height at the low-lying and densely populated suburb of Lyall Bay.

Yet during big southerly storms, on nights when grid power failed and sirens were snatched by the shrieking wind, many Outers in the affordable low zones felt Freedom’s Rampart wasn’t high enough. On nights when the seawall’s security lights were swarmed with spray and their feeble glow was all that delineated the wall from a much greater darkness, Outers swore they would pack up and move away in the morning, if morning came.

Dead low tide. Beyond Freedom’s Rampart, a ragged line of Saturday morning walkers and fortune-seekers were strung out along the low-tide track. The sea was big but the gale held it up and drove it back, mostly. Conditions were marginal in many sections and only the fleet of foot, desperate or foolhardy, would attempt the whole walk.

In the shadow of the seawall much of the time, they picked their way carefully. The storm had carved new hollows in the gravel, thrown together mounds, plastered the wall with logs, kelp and plastic so thickly that only the highest tagging was visible. Large trees, recently living, had joined the pile of debris. Wrenched from the soil like rotten teeth all along the South Island’s drowning coast and driven north by the storm, they were another hazard to be negotiated. Crane-bots which ran back and forth on the rail track along the top of the wall would commence clearance once the walkers had gone.

High up in the tangle of trees, plastic and debris wedged against the seawall at Houghton Bay climbed two young children, a boy and a girl, of ages maybe eight and six—it was hard to tell because they were so thin and serious, and the boy so earnest about his sister’s safety as he led the climb. With the same spiky hair and ragged woollen jerseys, the same brownness from dirt and days in the sun, they carried rubbish bags to fill with buoys and other sellable items. Many on the track below didn’t see them. They didn’t want to.

The sea’s noise, the sun’s flung brightness on the looming waves, the sudden shafts of sunlight among deep wells of shadow: there was nothing else like it. For newcomers it felt unreal, like the interface with another dimension. No familiar advertising caught and held their eyes; no sense of protection was offered by electronic surveillance; rescue services took an inordinately long time to respond to calls. Ladders on the wall every 25 metres climbing to emergency platforms were the only protection. There was real mortal danger.

Metal poles driven into rock marked the route over crags. New guide ropes had been hung. It was at these bottlenecks that fortune-seekers tended to distinguish themselves from walkers, through their excess weight and lack of fitness, confidence and appropriate footwear.

A large young man in a black Merino sweater and cargo shorts had wrapped himself around a steel pole halfway up a steep section and begun to weep, eyes shut, deaf to words of encouragement from above and below. Nothing unusual. A fit middle-aged walker in hiking boots climbed up, removed the man’s gumboots for better traction on the stone, unknotted him from the pole and helped him down, step by step. Lost in his shame the man didn’t believe the words of encouragement and kindness offered by strangers, the sincerity of their friendly pats on his back, nor their advice that he should take a breath and try again a bit later. He just wanted to get away, off the awful open coast and back to the safety of his apartment. But leaving wouldn’t be easy, returning against the one-way foot-traffic over the broken, riotously elemental track. The strangers’ unusual kindness and patience convinced him to sit a little longer at the bottom of the bluff, watch how others did the climb, and maybe try again.

The beach was dangerous, excluded from life-insurance policies. The whole coastline was changing and poorly defined, hammered by waves full of hidden debris and prone to unpredictable charges. But there was freedom in this sizzling and thumping no man’s land beyond the seawall. Freedom from crowds, concrete, screens, and the towers and growing congestion of the city. Most importantly for some, it was the only place in Wellington free from electronic surveillance. They could talk about anything.

One notable group, clustered in bright coats on a knuckle of rock, listened to a teenage girl in a red beret play a song on a piano accordion about the inevitable uprising of the proletariat.

For many the walk, with all its trials, was like a pilgrimage. Real insights awaited them, from real psychics who looked them directly in the eye and spoke freely and without constraint. A final climb would bring them to a flaxy shelf near Princess Bay, where the psychics sat in a short row of portable wooden stalls and peered out through small glassless windows.

Fortune-seekers believed themselves to be more than debt-ridden consumers or hard-workers; something other than the profiles and predictions the Machine based on their online activity; something more substantial than the size of their cyber-print. They were more than just lifters or leaners, Inners or Outers, human capital, victims or single votes in a rigged international system. They knew the deck was stacked against them. They wondered if there was a way to change that. They knew how little opportunity they really had and how increasingly unfair everything was. They wanted to know where their best possible future lay. The eyes in the glassless windows knew that and knew them.

In queues of varying length dependant on the teller’s fame, fortune-seekers hunkered down out of the wind as best they could. Against the vigorous white noise of the sea played the notes of gas fire and steam in box coffee stalls. Conversation between strangers was easy there, held in front of waves, against the seawall. Like condemned men sharing a last cigarette before a firing squad, they admitted hidden truths. It was easy to admit long-term unemployment, easy to speak of sickness, hopelessness, poverty and even loneliness. Communication with a stranger felt customary. It felt human. What a relief it was to speak to someone new without attracting anonymous abuse or advertisements.

Some spoke eagerly of the coming prophet, who would unite the warring, dying world and steer a path to peace and abundance for all.

‘It is written in the stars,’ said a man with a missing front tooth and a pilled sweater to two teenage sisters come to ask a fortune teller about future love. ‘He shall come and show us the way,’ the man declared as he brandished his chipped ceramic cup. ‘It is writ also in these coffee grinds.’

‘Awesome! We’d love to meet him.’

A low-slung rainbow blossomed in a haze of spray.

Boom. The rapid invasion of seawater elicited squeals from the sisters, but others in the queue, dull-eyed and dirty, hardly seemed to notice their feet getting wet. It was as if they were too intent on framing their question for the all-seeing eyes in the window.

Where can I find work?

What is wrong with me?

Where should I take my family?

Who can I believe?

Behind the protection of the seawall, the coastal suburbs seemed hunched beneath the gale. Streets were empty but for the occasional electric car and trolleybus. On Island Bay’s Parade, in front of one of the big old subdivided houses at sea level, a child’s rope swing hung from a dying pōhutukawa, its trunk wrapped in soaked hessian. Large urban green spaces were gone and the remaining trees wind-bent and depleted by disease. Outers were behind their wind walls, inside roofed sports arenas open 24/7 with by-the-minute rosters, inside sweaty indoor play centres, the large apartment complexes with mini-malls built for the flood of returning ex-pats, and in supermarkets which were the envy of the world despite their limited and rationed produce.

A kilometre inland from the sea-scoured coast lay Berhampore’s chronically overcrowded apartment blocks, built in the mid 2030s on ‘de-aquitised’ public land to help accommodate the capital’s soaring population. Violent crime and drug use was rife. Loud, bass-heavy music marked the boundaries of little kingdoms. Thirty-metre-high electronic billboards bookended the apartment blocks, advertising gadgets, screens and virtual reality worlds. The ads, paying for fairly regular building maintenance, played continuously above communal green areas with basketball hoops which had become the stripped and vandalised sites of gang battles.

A tall and underweight teenage boy with greasy hair and spots on his forehead looked down from a high window at a blood-soaked scrap of green cloth rolled by the wind into a concrete corner. It was his. Officially Withdrawn until last night (having gone six months since high school finished without leaving the family apartment), he had ventured out of his cyberworld into sluggish reality with a gang of fellow Green Ninjas to plant a bug in the indoor communal area at Kate Sheppard Block, where the Dark Knights were based. There had been an ambush. Retreat protocol was not followed. His gestured strikes were not recognised. The awful loudness of the yelling in the echoing space and the flurry of blows battering against his arms and head had quickly lead to the panicked confusion of the Green Ninjas’ retreat. It was terrifying. Blows kept falling. There had been blood in his mouth, running from his nose, strange and thick, and his head rang, and the Knights wouldn’t stop. He’d yelled, ‘I give up! We give up!’ and got a blow to the forehead in reply. The Knights were pitiless, crazy, punching and abusing the Ninjas as they ran outside, retreating to Ernest Rutherford. While they waited in a tight defensive ball by their home-block elevators, flinching and battered, terrified, more Dark Knights arrived, whooping with excitement. There were too many of them and they weren’t playing anything like in the game. Three of the five Ninjas fell and were kicked where they lay, curled up. Crying, short of breath, he had feared for his life. The whoop of a siren had scattered the enemy. In the sudden quiet he heard their cries of triumph float up into the night as they ran away across the complex. ‘The Green Ninjas suck shit!’ That could be me, he thought, looking down at the scrap of bloody green torn from his costume. I’m never going to be like my avatar. I’m never going out again.

Among the crowded apartment blocks and wind-protected consumer environments of Berhampore, there was one rare and notable patch of green—an oasis. On the site once known as Martin Luckie Park rose a perfectly round hill which appeared from a distance as verdant as a park behind the Wall on Mount Victoria.

The half-sphere stood 25 metres above the shabby subdivided bungalows and functional new apartment buildings clustered tightly around it. Curved and organic, with flax rattling and long grass waving in the gale, the hill was like a commemorative art installation, a reminder of the past, or a promise of a better time to come; but its soft, oxygenating and bittersweet presence was belied by the three-metre concrete wall topped with razor wire that encircled it. Longer acquaintance lent the dome-like hill a sinister, uncanny aspect, as if it concealed a communications dish, a tireless ear eavesdropping on all the conversations, purchases, searches and complaints going on around it.

As rubbish tumbled and clattered down wind-emptied streets to collect along the seawall (where it would be removed by crane-bots), and the giant electronic billboards repeated and repeated (a woman’s eye widened, a woman’s eye widened, a woman’s eye widened at the sight of a yet-to-be-revealed new gadget), a young couple emerged from their apartment block into the empty street.

Obese due to a sedentary life spent in front of screens and a diet of affordable processed food, the young couple propelled themselves forwards with careful rigour, focussed on the rhythm of step and swing. Wrinkle-free, with glossy wind-worried hair in abundance, the couple wore beautiful custom-cut suits: Burberry linen and Armani business, the latter made from hemp and recycled polyester. Local black-market workshops with bodysize-scanners, 3D printers and pirated software made high-end brand clothes cheap. It was called the liberation of the poor. Pendulous globes, drooping rolls and broadness of beam were stylishly concealed as the couple swung down the street in their shared careful rhythm. The wind flattened and billowed their clothes, their faces reddened, their mouths opened. As they began to puff and perspire, more Outers in bespoke clothing appeared in the street. Here and there the occasional used military chameleon suit blurred grey against the concrete.

Eye contact was infrequent and brief. Heads stayed down, bent into or away from the gale, bent partly perhaps from fear of street violence, or the labour of building their cyber-lives. Subsonic polyrhythms punched the air between gusts. Some walkers appeared tentative, as if they didn’t quite believe in the concrete they walked on. There were panic attacks. Some sat on the pavement and wept. Some turned back. Yet most carried on, and as they crossed the cracked concrete landscape, passed bus stops, dairies and fast-food outlets piping intoxicating aromas of hot fat and salt, it became apparent that something unusual was afoot.

From all directions they converged on the new round hill, moving faster as they drew nearer to it, as if something had snapped and released them. Eyes met. Unity of purpose was assured. The road around the hill could barely contain the flood of them. It was time. In one thrilling motion faces became balaclavas and ski masks. Voices cracked as shouts went up, tentative at first and then very certain.

Star Sailors is available from Victoria University Press.

Read a conversation with Darian Smith and James McNaughton about speculative fiction, fandom, magic systems, and the genre vs. literature divide.