How We Are: A Conversation with Steph Burt

The American writer and critic about living as two genders, poetry, criticism and the body.

On the occasion of Steph Burt's visit to New Zealand, Sarah Jane Barnett talks to the American writer and critic about living as two genders, poetry, criticism and the body.

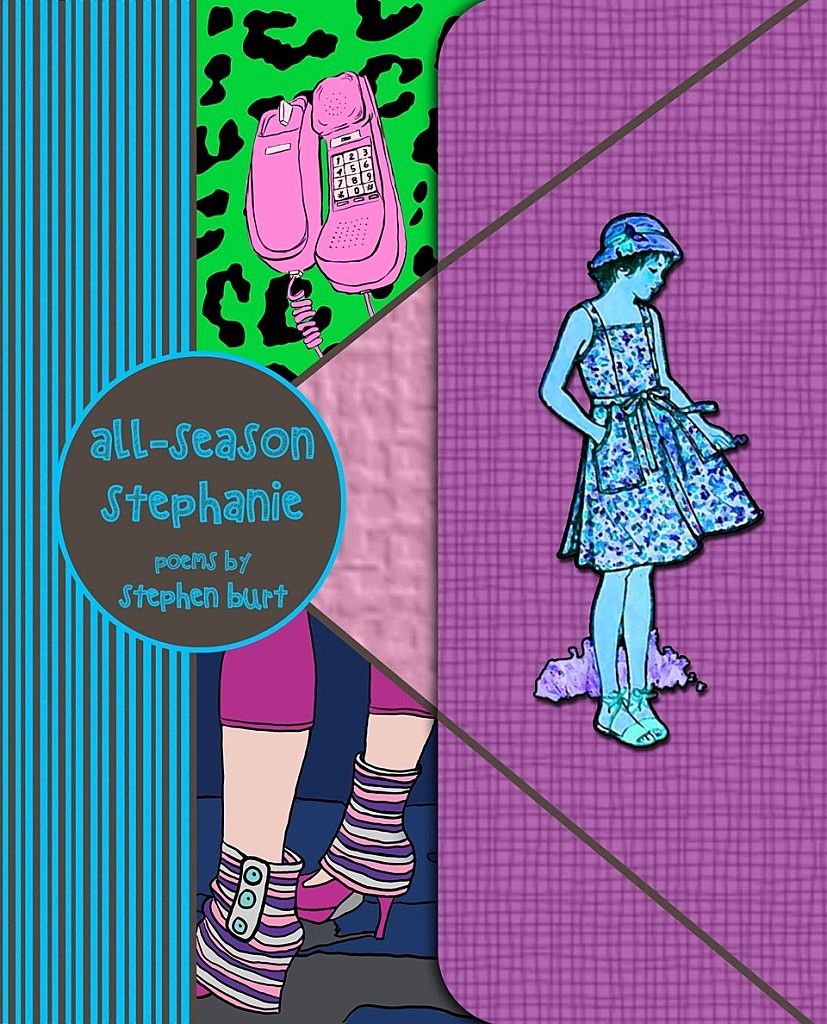

Poet and critic Stephen Burt has been described as ‘one of the most influential poetry critics of his generation’ (NY Times). Burt is a professor at Harvard University and has published three full-length collections of poems – Popular Music (1999), Parallel Play (2006), and Belmont (2013) – along with several chapbooks, most recently All-Season Stephanie (2015). Burt is also well known for criticism, most recently, The Poem is You: 60 Contemporary American Poems and How to Read Them (2016).

In 2012 the New York Times Magazine ran a profile on Burt with the headline ‘Poetry’s Cross-Dressing Kingmaker,’ identifing the poet and critic for the first time in public as transgender. Burt – who answers to Stephen, Steph, and Stephanie – has since written about having two genders in poetry and in essays such as ‘My Life as a Girl’ and ‘The Body of the Poem.’ Photo of Steph by Alex Dakoulas.

Sarah Jane Barnett: First, would you like me to call you Stephanie or Stephen, or simply Steph? In December you’re giving a public masterclass in Wellington called, ‘Close calls with nonsense, or how to read new poetry’ (the class sporting the same name as your book which was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award). What has brought you to New Zealand?

Steph Burt: Steph or Stephanie in person; Stephen is the name on the books. This summer I’m an Erskine Scholar at the University of Canterbury in Christchurch; they’ve brought me over – and by they I mean the university, but also the wonderful critic and Baxter scholar Paul Millar – so that I can teach a summer course in modern poetry. Of course I’ll be doing some readings and public events, in addition to traveling around both islands with our family, while I’m here.

SJB: You have such enthusiasm for helping people read poetry. Did you grow up with this love of language and literature? You’ve said, ‘I understand the world best, most fully, in words’; can you talk about what happens when you read a poem? I often think that poetry moves through the mind to create an experience in the body – that reading is performative and the poem is created new each time. What do you think about that idea?

SB: I think it’s correct. My colleague Helen Vendler (echoing a letter of Gerard Manley Hopkins’s) has described lyric poetry as a score for performance by the speaking voice: the poem becomes yours when you take it into yourself, which also means taking it into your body, your voice: both the body you have, and the body you wish or imagine that you ought to have.

That’s a general model for what happens when we read lyric poems. When I myself read a poem I also feel like I’m testing out the sonic and the semantic relations among all the words, to see whether I’ll want to come back to them. A good poem is a poem that I want to come back to, again and again.

I’m sure I grew up with a deep attachment to language, a sense that my world wants words. Too many words, maybe. I was a loquacious and deeply uncomfortable child who couldn’t stop trying to talk to adults. I remember doing a report on ‘Lycidas’ in what may have been third grade, because I had discovered it in a library, and copying out the beginning. Yet once more.

I’m sure I grew up with a deep attachment to language, a sense that my world wants words.

SJB: One of my main areas of interest, and where I think we share a common interest, is the relationship between poetry and the body. In your TED talk you said: ‘Poems can help … introduce you to feelings, ways of being in the world, people, very much unlike you, maybe even people from long, long ago.’ Do you think that’s one of the powers of poetry, that it allows us to step into the experience of the ‘other,’ that it encourages empathy and shows alternatives? In this regard, what makes the experience of poetry different from say film or music?

SB: Poetry can absolutely help us understand, or try to understand, the experience of people unlike us, though in certain ways it’s worse at that task than novels, worse than certain films (Mike Leigh’s, say) and worse than the best TV. (By poetry I mean the kind of poetry that we tend to write now: relatively short, richly patterned, not normally narrative – either lyric or modernist or both.) Short poems are worse than long narratives at telling us why people get to be the way they are, what social forces and choices create us; but short poems are the best at telling us how we are, what it’s like to be this or that, at presenting or simulating interiority. The same poem can use its arrangements of language, its echoes and overtones as well as its arguments, to show us at once what it’s like to be one particular character, and what kinds of feelings many of us have had.

Songs can do that too, but they’re more general, because they tend to use fewer words, and they depend on the music – poems use, as Yeats put it, ‘words alone.’ They don’t have to be explicit ‘I’ statements, don’t have be paraphrasable claims about feelings, either. Consider the end of ‘Cuchulain Comforted,’ Yeats’s last poem, with its feeling of peace and shock and failure together, as the late hero confronts – what many of us confront – the inadequacy of any powers human beings hold dear, the failure of everything humans can do in the face of eternity: ‘They had changed their throats and had the throats of birds.’

SJB: You’ve written about transgender poetry, and about poetry and bodies and gender. As someone cisgendered and with a transgender father, writing has allowed me to imagine her experience, at least textually and no doubt imperfectly. In one interview you talked about the way ‘a poem is always an alternate self, an imaginary body, a form of transport.’ Has poetry helped you live as two genders? Do you see it help others? In part, does your enthusiasm for helping people read poetry have social or political reasons?

SB: Yes and yes and yes! What books have helped you as you think about her? What books does she like? Or do you feel – as many trans people now feel – that there aren’t yet good books, aren’t yet the right books, to depict our experience?

I do think poems are imaginary alternate bodies: they are representations of speaking selves that we could have, even when they do not contain the word ‘I.’ Some poets find that these speaking selves stick close, at their best, to the poet’s real earthly body; others delight in the distance. Many do both, even within the same poem.

That’s true for poetry generally. As for my poetry, I have been writing what I saw as transgender poetry since I began to publish poetry – the first poem in my first book has the line ‘If I were a girl, I would be a girl,’ twice! – but apparently nobody noticed until I came out through interviews, in prose. Of course for most of the 2000s I wasn’t presenting as female in public, either – I thought I could be happy without doing so, and I was, for a while. Being out as trans – as someone who lives in two genders (I haven’t transitioned to female full time and have no plans to do so any time soon) – has helped me write other poems, more poems, about my own transfeminine experience, including the chapbook All-Season Stephanie, available now from Rain Taxi Editions. I can write much clearer poems about being a girl and not a girl, about the girl I wish I had been, about being a guy who isn’t a guy and doesn’t want to be a guy.

I sometimes get email, or letters, from other trans people, and I meet more of us when I do public readings; sometimes it’s people who are barely out to themselves, who have just figured out that they need to do something about this feeling of having the wrong body, of missing out on much of who one is. I also get emails and letters about the other identity category that my new poems often describe, which is parenthood. I’ve told people not quite jokingly that Belmont was 1/3 trans girl poetry and 2/3 parenthood poetry, and the next full-length (Advice from the Lights, out in 2017) will be the reverse.

SJB: You’ve also said that you want to be several versions of people – from Stephen to Stephanie to ‘a techie tomboy’ – and I wonder if that is something that literature does for both writers and readers? Everyone has to make choices, and this means there are lives we cannot live. For you, does writing include an element of ownership – a claiming of experience, or the right to experience? A way to say, am I this and this? To validate in what can be an invalidating world?

SB: Yes, absolutely! That said, I don’t want to say that poetry is wish-fulfilment: it’s never only that, if it’s any good.

When a poem does what it’s trying to do, what it ought to do, that poem also asks questions that it can’t answer; it asks what doesn’t make sense, what can’t be done, what’s still unreal, as well as validating, claiming, making up, compensating for what we can’t have, what language can’t do, in the literal, instrumental world of plain prose.

Since I am writing in mid-November, just after the American election, and since we are thinking about what poems can and can’t do, it seems worth saying something extra about political poetry. Every topic, every kind of experience, can be called political, since the polis affects everything when it malfunctions, and many things even when it functions well. It’s important for poets who want our poetry to have political effects (not just to address political subjects) to recognize what effects we can and cannot have. And those effects vary by style, by writer, by audience. Danez Smith and Rachel McKibbins and Patricia Lockwood (who are otherwise quite dissimilar) have, I think, some wonderful political effects that my own poetry cannot have.

As I read more news this morning, and every morning since the election, I find it hard to wall off public life, to concentrate on the real good that poetry and poetics can do for individuals. I think that the United States, where I live, and to which I expect to return in 2017, is going to look like a different country in a few years: it might look a lot like Italy under Berlusconi, like Mexico (in terms of political culture) during the 1980s, or (this would be a lot worse, and seems less likely) like Turkey or Hungary now.

I’m rethinking the role of poets and poetry in light of that bleak prognosis, but I’m not sure how different my conclusions are going to be: it may be that poetry preserves, for its readers, a space of individuality, a space where language serves imagination, a way to be somewhere and someone else, as well as a way to be truly oneself, when the language of prose and news and obligation and hard facts and recent history will not let us do any of that, because reading the news is a lot like being hit in the face.

But if that’s what poetry is for, then we also need a language of not-poetry, a language of organizing for a better future together, and of facing tough facts. We need writers like Orwell, but also writers like Frame and Woolf. And the poetry I recognize, the poetry I know how to describe, is mostly like Frame, like Woolf.

SJB: On being pretty and being Stephanie you’ve said, ‘Maybe I just want to feel pretty, or to look pretty.’ I often think that poetry – being made of language – can give us an experience of beauty that’s more essential and enduring than worldly beauty. Human bodies are fallible and imperfect. We make mistakes, we excrete waste, must clean our bodies, we thin, sag, forget to call our mothers, are cruel or clumsy. When I don’t feel pretty, or kind, or right, poetry reminds me that other people feel this way. It also reminds me of our inner and common human beauty. Tell me about your experience of beauty? Does poetry make you feel pretty? Or human? Or…?

SB: It’s funny that you mention feeling human, since a short stack of poems from my next book use nonhuman speakers: a hermit crab, kites, cicadas, a water strider, an electric torch (flashlight). I love what you say about beauty. It’s quite close to Shakespeare’s sonnet 18!

Prettiness isn’t beauty; it’s a subclass of beauty that acknowledges details, surfaces, small scales, and invites being labelled childish, or feminine, or femme. I’m a fan of pretty; not everyone is. I say more about prettiness in my essay, 'Nearly Baroque.'

I’d like to be able to get back to a mental state where I can endorse the rococo, the nearly Baroque, the self-consciously pretty, the style that revels in its own elaboration, as an appropriate response to our time; I’d also like to get back to the mental state where I can be proud of left-liberal incrementalism as a mindset that can improve the world. That may be a mindset appropriate for New Zealand, and for Canada, and for other countries, including developing countries (Singapore?) where the idea of progress still makes sense.

“It’s okay to read some poems, or all poems, intuitively, irrationally, and just love them. Let the poems you cherish speak to you.”

SJB: For me to understand a poem I need to spend time sitting with it, and to then revisit it in different moods and times of day. I’ve spent the most time with Robert Hass’s ‘Meditation at Lagunitas’ but have recently moved on to his poem, ‘Consciousness.’ I am getting to know it as I would a friend. What are the things you encourage readers to do in order to get to know a poem?

SB: Read it over and over. Copy it out freehand, or memorize it (I don’t memorize as many poems as I should). Annotate your copy. Read other poems by that poet. Imagine how lines or phrases could be otherwise; rearrange them, or plug in synonyms. Identify its features (diction, pace, sentence shape, dominant metaphor, kinds of line break, kinds of meter if any, kinds of free verse if not) and try to figure out what each one does.

That’s what you do if you’re a fairly analytical reader, like me. It’s okay to read some poems, or all poems, intuitively, irrationally, and just love them. Let the poems you cherish speak to you.

SJB: What are some of your favourite poems (or passages from poems)? Tell us about why they are beautiful to you? I’ve read that you’re interested in James K Baxter? What attracts you to his work?

SB: Baxter is a poet of world importance, like Auden or Stein or Rilke, and I have been banging my head against walls for 20 years trying to make Americans read him. My longest attempt is in Believer Magazine (warning: paywall after the first few paragraphs). Baxter sounds great, he changes from book to book, the last five years are entirely original both in the way the lines work – ‘He judged the town and found it had already been judged’ – and in their attitude towards Western culture, non-Western people and culture, art, literacy, social practice, and family. It seems to me that, like Whitman, he created a new kind of poetry by becoming a new kind of person. Of course there was hubris involved. But the poetry is both versatile and sonorous and instantly recognizable. He expanded what English could do. And if he had ever spent time in the United States, Americans would know it. Aaaargh.

I’m writing a book of prose right now that’s going to be called Don’t Read Poetry; the idea is that learning how to read poems means embracing different poems for different reasons, different desiderata, rather than claiming that all the best poems work one way, or promulgate beauty in the same way. Some of my favourite poems at the moment include Keats’s ‘To Autumn,’ Richard Corbett’s ‘Farewell, rewards and fairies,’ Marianne Moore’s ‘The Steeple-Jack,’ Paul Muldoon’s ‘Cuba,’ all Terrance Hayes’s ‘Blue Terrance’ poems, Elizabeth Bishop’s ‘Poem (About the size of an old-style dollar bill),’ Juan Felipe Herrera’s ‘187 Reasons Mexicans Can’t Cross the Border,’ and Randall Jarrell’s melancholy ‘The Player Piano’: ‘If only, somehow, I had learned to live! / The three of us sit watching, as my waltz / Plays itself out a half-inch from my fingers.’

Steph Burt's public masterclass, steered by Bill Manhire, will be held on 12 December, 2016 from 5.30 pm - 7.00 pm, at City Gallery, Wellington.