What's The Frequency, Steven?

Sam McChesney on how a politician built a radio empire

New Plymouth, New Zealand, 1987. Tony Gadd is bashing hopelessly on a studio door. He clobbers it with increasing desperation, pausing occasionally to peer through the windows and yank on the handle. Behind him, past the rows of Holdens and Datsuns parked in the street, the sea glows orange. Gadd begins to sweat.

A few minutes down the road at the Egmont Steam Flour Mill, Steven Joyce is beginning to panic too. His normally cheerful face, topped by dark, wavy hair and bisected by a neat mustache, is a picture of worry. He’d barely started what had promised to be an epic drinking session, but the radio, playing over the venue speakers, has fallen silent. Joyce checks the radio’s pilot light – still on. Gadd, his employee, is definitely not on air. He assembles a gaggle of similarly inebriated friends, and they set off to the studio.

When they arrive, they quickly realise what had happened – Gadd had left the studio to pee and managed to lock himself out. Joyce quickly lets Gadd back in, and once the show is back on he joins the others in laughing at the announcer’s idiocy. This is a good story, Joyce decides. He keeps telling it for the next thirty years.

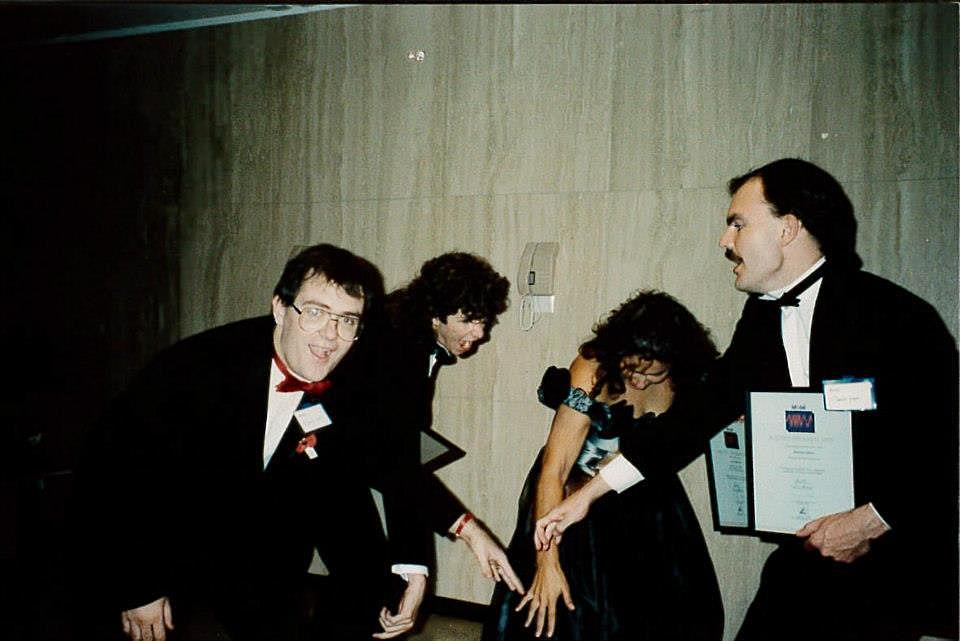

After all, this isn’t just any old Monday night on the piss. Back down the road, the regulation bottles of Taranaki Bitter Ale are tapping against plastic glasses of Lindauer and Cold Duck, and mingling with the Ray Bans and backcombs of the twenty-something set are businessmen in white chinos and loud shirts. They’re here to celebrate the resurrection of Taranaki’s hottest radio station, Energy FM. Thanks to the damn bureaucrats, the station had endured almost two years of silence. Thanks to Gadd’s bladder, they’d just endured another heart-stopping half hour.

*

Joyce had loved radio for as long as he could remember. The son of Paraparaumu supermarket owners, he grew up surrounded by till receipts and spreadsheets, and as a teenager he fell asleep to the commercial stations of the seventies. When the broadcasts switched off at midnight, as they usually did, he felt cheated.

As much as he admired it, the industry at the time was a closed shop. Byzantine regulations meant the established stations – usually state-owned – were heavily insulated from competitive pressures. Most NZBC announcers were given BBC voice training, and those allowed any creative licence – such as a young Paul Holmes – were confined to the middle of the night. When he was thirteen, Joyce first heard Holmes present the Coca-Cola All Nighter – an exhilarating blast of energy and irreverence. Yet within months Holmes was gone, fired by the NZBC after a fairly tame prank call to the Archbishop of Canterbury.

By the mid-seventies, frustration within the industry was beginning to grow. The government of the day rarely granted commercial licences and, despite the technology being widely available, it refused to adopt FM broadcasting. The result was a spate of pirate stations. When Auckland student outfit Radio Bosom, which began in 1969 as a stunt broadcast from a boat, was finally granted a licence to produce short-term broadcasts in 1975 during Capping and Orientation, the conditions were stringent: it was to be a purely informative, non-commercial, low-power broadcast aimed solely at university students. No music, no entertainment. Over the following years the students’ association applied repeatedly for an expanded licence, while unofficially encouraging pirate broadcasts and playing these – illegally – over its campus speakers. They wore the regulators down, and by the end of the decade Radio Bosom – by then shortened to Radio B, and now bFM – had attained a semi-commercial licence, paving the way for other student stations across the country.

In 1981, Joyce moved to Palmerston North and enrolled at Massey University. He was studying to be a vet (as a youngster, he’d tried to train his parents’ horses), but at the end of the year he missed the cut. That year, the student union at Massey started its own station, the brilliantly/tragically named Masskeradio. Mercifully, the name didn’t last; by 1983, when a shy Joyce – now a zoology and economics student – finally plucked up the courage to approach the station, it was called Radio Massey.

In true student media fashion, the station manager – a woman called Maxine Parker – briefly showed Joyce the ropes, then immediately put him on air. After about half an hour, Parker left the studio to get a coffee from the student union building. “You seem to be doing alright,” she told Joyce. “Just work your way through those records over there.” Just like that, he was on his own.

By the standards of student radio, Joyce was hardly a music geek – a longstanding devotion to REM aside, he has rarely shown any real passion for it – and now he was stranded in the studio with an intimidating stack of obscure vinyl. Reasoning that most bands put their strongest songs on side A, track one, he proceeded to play every side A, track one from the stack. In the middle of a particularly ponderous number, he received his first ever listener call. “You might want to play those EPs at 45 RPM,” the caller suggested, “it might work a bit better.”

Despite his slow-motion debut, Joyce became a fixture at Radio Massey. He made plenty more rookie mistakes – leaving the mic on during ad breaks, swearing on air – but then, so did everyone else; they were all rookies. In 1984 he was appointed news editor, and later in the year he became programme manager. The ethos of the time, he recalled, was that if you hung around you’d soon land a better job.

Radio Massey had close if occasionally fractious ties to local Palmerston North station 2XS. 2XS was a commercial station comprising professional broadcasters, yet it saw Radio Massey as a valuable talent pool, and its staff, particularly station manager Larry Summerville, were happy to help out their amateur counterparts. But Summerville was miffed when Parker’s successor at Radio Massey, Quentin Bright, made the switch to FM broadcasting in 1984, beating 2XS. Further awkwardness ensued when sound engineer Don Raine began helping out at Radio Massey; Raine had only just been fired from 2XS for punching out Summerville at a party.

"You had young overseas workers with high disposable income who wanted the stuff they had back in London, and Europe, and America. Then you had an older, more farming focused and more conservative adult market, who’d wear a brown polyester suit to a wedding" - Quentin Bright on 1980s New Plymouth

Raine was providing technical support for Joyce’s pet project: a series of political specials leading up to that year’s general election. Joyce secured interviews with prominent political figures including Labour’s Geoffrey Palmer, Social Credit’s Bruce Beetham, and peace campaigner Rod Alley. A group of them would produce the shows at Raine’s flat, then shuttle the tapes to the studio in Joyce’s Morris Minor.

Hardly anybody listened to the specials, but the process of producing them was the first time Joyce had seriously considered radio as a profession. A group of the station’s employees, including Joyce, had regular drinking sessions at Quentin Bright’s flat, and they would talk, as students are apt to do, of changing the world together. As Joyce put it, “our feeling was that commercial radio wouldn’t necessarily see our innate and huge talent” – the industry was still “reasonably closed-shop”, and there was also the small matter of Raine’s recent sacking. (Through his press secretary, Joyce declined multiple requests for an interview – many of the quotes in this article are from an oral history he recorded with Gerard Duignan in 2004.) Before long, they settled on a plan to start their own station as a way to fill in the summer.

The plans eventually coalesced around a group of five, all of them Radio Massey employees: Joyce, Bright, Peter Noldus, Jeremy Corbett (now the host of TV3’s 7 Days), and Darryl Reid. (Raine by this point had moved to Australia.) Bright, a passionate music fan, was to be station manager; Joyce was in charge of programming; Corbett, the funniest of the group, was the lead announcer; and Noldus was the sales manager and resident computer whiz. Reid was a bit of a wildcard. Noldus suspected he was just in it for the women. They put him on the midnight to dawn show, where he could do the least damage.

*

A few months later, they were in New Plymouth. They’d chosen the city for its lack of a commercial radio station, as well as its connections to the group – Joyce and Bright were both born there. The past few months had been spent recruiting amongst their mates, and scraping together personal loans from local businesspeople. During another drinking session at Bright’s, they’d also come up with a name. After the guys had thrown around a few “suitably tragic” ideas, including Cow FM and Milk FM, Joyce’s then-girlfriend had suggested Energy FM – a nod to both the station’s ethos and the region’s booming oil industry.

New Plymouth at the time was defined by its twin pillars of dairying and oil, creating an odd mix of rural and cosmopolitan cultures. “We had fashion boutiques in New Plymouth that would stock designers you could only find elsewhere in High Street in Auckland,” Bright says. “You had young overseas workers with high disposable income who wanted the stuff they had back in London, and Europe, and America. Then you had an older, more farming focused and more conservative adult market, who’d wear a brown polyester suit to a wedding. But a lot of them had kids, kids who were our target audience, whether they were at high school, at polytech, working in the oil industry or all the support industries around it.” And the kids wanted something decent to listen to. Radio Taranaki, the Radio New Zealand-owned AM operator, played a narrow range of tedious mum rock, and the market was hanging out for a fresh, youth-oriented station.

However, others had the same idea; the group arrived in New Plymouth to discover that not only were there several other groups looking to start commercial stations, but at least two had also called themselves Energy FM. “Obviously it was a very good name, just not that original,” Joyce recalled. The group had expected to gain a six-week commercial broadcasting licence with few hassles, but quickly found themselves in a many-sided battle to get on air. They eventually won a licence, but had to share it with a competitor, Peak FM: the two stations were allowed only four weeks each. Worse, the regulations at the time were set up to protect existing full-time broadcasters – in this case Radio Taranaki – and Energy FM was barred from going on air commercially until after Christmas.

Angry at the rigged system, Energy FM went on air early as a non-commercial broadcaster. Joyce and Noldus used the pre-Christmas period to plug a charity concert they’d organised with a promoter friend. The concert – featuring Dance Exponents, Peking Man and The Narcs – put Energy FM on the map, and the ad-free broadcasts pulled in large numbers of listeners.

It was an early competitive advantage, but among the group, money was understandably tight. They had each chipped in a hundred dollars to register as a company – Joyce had to lend Darryl Reid his hundred – and during one of the group’s many loan applications, Joyce listed his suit jacket as his only asset. Over that first summer, the five of them went on the dole, and all the staff were hired under the student unemployment scheme (“it was Bludger FM,” Bright recalls). Except for those with family in the city, the entire staff lived together in one flat – about fifteen of them in total. The beds did double or triple shifts, people staggering back from the studio at various times of day to catch some sleep where they could.

The studio itself was above the AA building (the car variety) on Powderham Street, a few blocks from the centre of town. The walls were lined with egg cartons (an effective sound suppressant) that they had solicited from a local school. The wires were held together with cellotape, and the faders had been liberated from Radio Massey. Upstairs, with no air conditioning and in the middle of summer, the studio was sweltering and the egg cartons stank, so the windows were permanently flung open. The revving of engines from the AA testing station regularly drifted onto the airwaves, and locals soon learnt that if they stood on the pavement beneath the studio, they could shout song requests up to the presenters. It was a glorious mess.

Over that first summer, Joyce and Noldus emerged as the station’s leaders and business brains. Noldus excelled at sales, a role he had landed in by default. None of them had any sales experience, so Noldus had volunteered – mostly because the alternative was the libidinous Darryl Reid. Noldus was a few years older than the others, and when they first met him he was married and working at the post office. They called him Gramps (after all, he was almost thirty) and poked fun at his receding hairline. Gramps had the last laugh: his hair is still intact.

The team treated Joyce with similar irreverence. He was “spaghetti-strand thin”, and they’d affect mock concern for his safety – perhaps he’d be blown away by the wind, or, somewhat more creatively, beaten to death by his own mustache. Bright used to call him the Pipe Cleaner.

"He was a bit of a perfectionist, so for people who didn’t quite come up to scratch, he’d tear one off them in no uncertain terms" - Peter Noldus on Steven Joyce

When former colleagues describe Joyce’s personality, the same words crop up over and over: “focused”, “hardworking”, “driven”. His work ethic was obsessive, occasionally irritating his more laidback co-workers. Everyone pulled the occasional all-nighter – there were mattresses in the studio for that purpose – but Joyce probably did it the most; Corbett lost count of the times he arrived to host the breakfast show to find Joyce “hanging upside down from the ceiling”. Corbett made sport of these early hours; as Bright puts it, Joyce was “legendary for getting up at the crack of noon”, and before his first coffee he was dysfunctional and cranky as hell. Rather than stay out of his way, Corbett and Bright – the station’s chief pranksters – needled him mercilessly.

Joyce had a head for numbers – as he put it, he’s “always known the value of a dollar” – and he became the station’s de facto accountant. As programme director, he had a relentlessly commercial focus. “Some of the guys, particularly Quentin and Jeremy, had this student background and wanted to play weird songs that are generally a commercial disaster,” Noldus recalls. Joyce’s job was to keep them in line. Joyce and Noldus bought a Commodore 64 and wrote a playlisting programme from scratch, giving two-hour rotates to the most popular songs.

As Joyce tells it, his pet hate is meddling management that stops people from doing their jobs. He strived to be the opposite. “I love working with people, and I love removing obstacles from their way,” he said in 2004. “I’m a believer that people are not dumb. People are intuitively pretty sensible. And so if you show them the same facts and figures that you’re facing, they’ll come to the same sorts of decisions – or you’re wrong.”

Others paint a slightly different picture. “He’s always had pretty strong ideas about how things ought to be done,” Noldus told me. Many staff saw Joyce as “forceful and autocratic”, and he could be harsh in his methods. “He was a bit of a perfectionist, so for people who didn’t quite come up to scratch, he’d tear one off them in no uncertain terms,” Noldus said. “People were a little bit scared of him. But generally people respected him, because when he wanted something, he was right.”

*

From early on, the plan had been to produce two summer broadcasts, then apply for a full-time licence. The guys went their separate ways during 1985 – Joyce returned to Radio Massey as station manager and many of the group joined him; Bright and a few others stayed in New Plymouth and worked at the oil fields – and regrouped the following summer. This time there was no competition – Peak FM had lost a lot of money last time out, and hadn’t re-applied for a licence – so Energy FM were allowed to broadcast commercially for the full six weeks.

"It was too tough, it was completely unfair, and we were pawns in a bigger game. But then finally you win, and it’s worth holding on for" - Joyce on the early days of Energy FM.

In April 1986, the station finally applied for a full-time broadcasting licence. Opposing them was Radio New Zealand (RNZ), who wanted to start a new commercial station targeting the same demographic. At the time the government’s position was that any RNZ application to the Broadcasting Tribunal ought to be approved automatically; although the Tribunal was an independent body, it was under huge political pressure. Coinciding with Energy FM’s application was the establishment of TV3, and a related surge in Tribunal hearings. Under-resourced and fed up, the Tribunal members all but went on strike. “At the end of our three-day hearing the Tribunal said ‘we reserve our decision’ and went quiet,” Joyce said. “Every time we rang up the Tribunal office there was nothing.”

What followed was an agonising, year-long wait for a decision. The team filled in the time with more easily-approved short-term broadcasts: a winter broadcast in June to July 1986, followed by another summer broadcast. That year Don Raine, their friend from Radio Massey, returned from Australia and joined the team. But the long-term future remained a mystery. Their lawyer, Brent Impey (the future CEO of MediaWorks; his assistant was Simon Dallow, the One News anchor) remained optimistic, but to the rest of them the chances of even getting a decision, let alone beating RNZ, seemed remote.

During those months in limbo, the team gradually disbanded. Quentin Bright left for 91ZM, then owned by RNZ. Jeremy Corbett moved to Perth to be a computer analyst. Darryl Reid, by all accounts, disappeared from the face of the earth. (His whereabouts have been a complete mystery for almost thirty years.) Before long Joyce, Noldus and Raine were the only ones left. All three were flat broke and still had no idea when, or if, they would get a licence. Exhausted and despairing, Joyce fell ill. Eventually, in early 1987, the group decided that only two of them could afford to look after the dormant project; one of them would have to get a job.

Even that plan dissolved; before long, they all had jobs. Noldus went to Radio Avon in Christchurch, Raine to One Double X in Whakatane, and Joyce to a PR agency in Wellington. Work on Energy FM stopped entirely. “We went through a huge amount of self-doubt,” Joyce recalled. “It was too tough, it was completely unfair, and we were pawns in a bigger game. But then finally you win, and it’s worth holding on for.”

In May 1987, two weeks into his new job, Joyce received a call. Come up to The Terrace; the Tribunal’s decision is ready to collect.

“Sure,” Joyce said. “Do you think I’ll like it?”

“I think you’ll love it,” came the reply.

*

After a year of purgatory, there was little remaining of Energy FM. Their original staff had almost all moved on, and the ancient equipment wouldn’t hold up to full-time broadcasting. Even their old studio was gone, the decrepit AA building having been demolished.

Joyce, Noldus and Raine set about rebuilding the station from scratch. A new studio with professional gear would cost around a million dollars, and bank loans were out of the question: Rogernomics was in full swing, and interest rates were well over twenty per cent in a desperate attempt to hold down inflation. The last time they’d asked for a loan, the bank had offered them five thousand dollars if Joyce’s parents put up their supermarket as collateral. Joyce had told them where to go.

Prior to the Tribunal hearings they’d appointed a board of directors, and the chairman of that board, local businessman Norton Moller, was their main financial backer. Moller helped them canvass Taranaki for the rest of the funds they needed, where they found no shortage of goodwill investment. Energy FM was thrilling, irreverent, popular despite (or likely because of) its chaotic nature. In a provincial city, it was everything the stale, dreary Radio Taranaki wasn’t. And even if no one could be sure of a return, FM radio was one sexy investment.

Somewhat less friendly was the newly-formed Department of Conservation. Raine wanted to broadcast from the Hen and Chickens transmission site on Mount Taranaki, but Energy FM were the first commercial operators to use the site and DoC’s pencil-pushers were being highly pedantic about the station’s transmission rights. Noldus was eventually dispatched to the DoC offices in Whanganui, with instructions to camp out until the department approved their request. He came back smelly and successful.

On 30 November 1987, Energy FM finally began broadcasting. When Joyce showed investors around the new million-dollar studio they were suitably impressed (no egg cartons!), and that night they threw a big bash. Around half-past seven, Tony Gadd got up from his seat to relieve himself.

*

By the middle of 1988, Energy FM was pulling in 38 per cent of the 10+ demographic, making it one of the most successful new stations anywhere in Australasia. The station had kept its anarchic atmosphere, and had developed a flair for self-promotion. Andi Brotherston, who joined Energy FM as breakfast host at the beginning of 1989, says she “probably met every single person in Taranaki” in her five years at the station.

“We were out two or three nights a week, pouring drinks in bars, and MCing gigs and promotional events, and handing out Mars bars, and having fashion shows to raise money for surf-life-saving clubs,” Brotherston told me. “We were incredibly promotionally active, and it was bloody hard work.” Joyce would later admit that “we went nuts, and created something that was unsustainable. We had a small staff, we did everything, went everywhere, and created a pressure that burnt out a lot of us at some point.” At the time, though, they had a blast. “Part of the reason we were so successful is that everyone knew we were having a great time,” Brotherston says. “Everyone wants to be associated with something fun.”

Despite the revelry, Joyce was realistic about New Plymouth’s limited appeal. The local economy had slowed down in the wake of the 1987 stock market crash, and the city was no longer the upbeat, youth-heavy place it had been in the early eighties. Joyce’s abiding memory is of countless farmers grumbling about “tough times”. As he put it, New Plymouth was “not where you want to end up”. Instead, Energy FM became a finishing school for young talents: over those first few years Brotherston, Martin Devlin, Rick van Dyke, Cliff Joiner, Chris Forster and Kate Rigg all passed through, usually for one or two years only.

Joyce, Noldus and Raine remained tight. “They were really good mates,” Brotherston recalls. “They had very defined lines, it was a very straight up, healthy relationship. Don was very much the production and sound expert, and Peter was very much the sales expert.” Joyce, meanwhile, was in the mastermind role of programme director, which put him in charge of every piece of content that went on air. He excelled at giving listeners what they wanted. As Brotherston tells it, Joyce always had an innate talent for reading the market and “taking the pulse of the nation”. Today, Brotherston sees Joyce as the driving force behind many of National’s populist positions. “He’s always had a really acute awareness of where most people sit.”

Although Joyce never spoke about a career in politics, Brotherston always knew he would end up running for parliament, most likely for National. In fact she told him so in the late nineties, a few years after she’d left Energy FM, and he responded coyly. To her this only confirmed things. “He doesn’t do anything by accident,” Brotherston told me. “It was always planned.”

Despite his gift for drawing in listeners – and his ongoing role as breakfast show presenter – Joyce’s mind was always on the business. He used to ask every new recruit to name the most important part of the station. They’d usually guess the listeners, or occasionally the staff or artists. Joyce would immediately put them right: the most important people were the advertisers. At promotional events there was a clear policy: keep the clients well hydrated, and always let them win at pool.

Even when things went badly, they went well. A few months after Energy FM started broadcasting, Cyclone Bola hit Taranaki. The storm tore the roof off the studio building. They all came to work regardless, even as the carpet billowed up and the whole place seemed to fall down around them. Energy FM continued to broadcast and reported on the cyclone as it passed through. They sent Cliff Joiner, then a cub reporter, out to Okato in an almost comically unsafe Suzuki SJ, a boxy little SUV that looked ready to tip over at any moment. With a radio transmitter on board, the Suzuki ended up as a go-between for the town and Civil Defence, and Energy FM’s coverage of the cyclone bagged them their first NZ Radio Award.

*

By the end of 1991, chairman Norton Moller suggested that Energy Enterprises expand. Mostly he was worried that without a new challenge Joyce, Noldus or Raine would get bored and wander off. Over the past few years, the media landscape had completely transformed. The broadcasting industry was one of the last to be deregulated by the fourth Labour government, but with the Broadcasting Act 1989 and the Radiocommunications Act 1989, all the stifling regulations were finally ripped away. New Zealand now had the most open radio market in the world, and new stations were popping up everywhere. One such station was Coastline FM in Tauranga. A few months earlier Barry Colman, the founder of National Business Review, had bought Coastline seemingly on a whim; he had barely invested in the station since taking it over, and it was struggling.

The three of them travelled to Tauranga to inspect the station, and found a city with a completely different vibe to New Plymouth. “In Taranaki we were always in decline,” Joyce said. “But I remember going up Cameron Road on my first time in Tauranga thinking, ‘Wow! Look at all these businesses! This is just fantastic!’.” After the stock market crash, Tauranga had become a destination for newly redundant workers to move and open up stores. Once Moller had negotiated the deal, they agreed to send Noldus, the sales expert, to run the station, and Noldus grabbed the opportunity with both hands. “Pete loved it,” Joyce said. “He made it quite clear: ‘I’m never leaving Tauranga!’ He found the lifestyle option and went for it.”

Joyce was always a fan of the “fantastic radio station”, and even Noldus admits that “it became obvious that The Rock had something special, and that the people who liked it, liked it a lot”

Joyce’s next big move was prompted by a challenge close to home. By 1994, at the age of 31, he’d retired from the air to become a full-time CEO. That year, Joe Dennehy and Grant Hislop invaded Energy’s turf, starting Rock 100FM in New Plymouth on a low-power frequency (LPFM) – a technology Joyce had previously ignored. It soon became clear that an LPFM – broadcasting at a maximum power of one watt – was more than adequate for a small urban centre like New Plymouth. Rather than buy up the local competition, in July 1994 Joyce travelled to Hamilton to nab Dennehy and Hislop’s entire network: The Rock, its sister station The Buzzard, and its regional offshoots. He completed the deal in a rush, only to discover that the network was a disaster, losing thirty to forty grand a month. Joyce was dispatched to Hamilton in November and was met immediately with Dennehy’s resignation. The situation rapidly deteriorated.

Even before Dennehy walked, Joyce and the board had decided to rebrand The Buzzard. The Buzzard had long suffered from identity issues; it was an urban station focused on dance music, but with the look and feel of a “big, mean, ugly” rock outfit. Noldus thought it was a joke. When Waikato’s Kiwi FM rebranded to The Breeze, Joyce saw an opening for a commercial, Top 40 station in the mould of Energy and Coastline. And so in September 1994 The Edge was born, with a shiny new aesthetic and a pop-heavy playlist. The on-air lineup had some of the company’s most exciting young talent, including Martin Devlin and Jay-Jay Feeney.

But when the ratings arrived that November, The Edge, along with The Rock, had tanked. It was the burgeoning company’s first real misstep; besieged by furious clients, Joyce went into “survival mode”, burying himself in spreadsheets and sales graphs as he desperately tried to save his Hamilton stations. The Fountain City was meant to be Energy’s big break, an opportunity to finally crack into a larger market. “The revenue potential was much greater,” Noldus recalled, “but not with a couple of stations that sucked.”

This, perhaps, was harsh on The Rock. Joyce was always a fan of the “fantastic radio station”, and even Noldus admits that “it became obvious that The Rock had something special, and that the people who liked it, liked it a lot”. But the bro-heavy station was much less universal in its appeal than Energy FM or Coastline, and running it was “a whole new introduction” for the pop-oriented Joyce.

Joyce remembers Hamilton as a “wild west town”; which is to say, it was full of angry white men with a taste for anarchy. The Rock revelled in its bogan milieu; it was a ramshackle outfit run off the smell of the proverbial oily rag, although huffing petroleum may also have been a more literal pastime. Breakfast host and station co-founder Mark Bunting had quit just before the takeover, leaving two junior jocks, Nick Trott and Rog Farrelly, as a stopgap. In the following months Hislop would regularly come to Joyce with concerns about Nick and Rog’s on-air swearing and “ropeable” antics; Joyce, up to his neck in shit, would invariably reply that he was too busy to fire them. Maybe next month. Nick and Rog went on hosting the morning show for twelve more years.

By June the following year, Joyce had overhauled the sales team, plugged various budgetary holes, and finally brought the network back to its feet. He’d become pretty good at this sort of thing. “The whole enterprise was always lurching from near catastrophe to near catastrophe, particularly in the first few years,” Noldus told me. More often than not, Joyce was the one to patch things up – presaging his career in government, where he has become National’s “fix-it man”.

*

Over the late nineties, Energy Enterprises grew into a major player. In 1997 the company merged with Radio Pacific, and began buying up stations across the North Island. During that decade, the market was a free-for-all. “It always pissed me off that we had to go through this big long application with the Broadcasting Tribunal to get Energy FM off the ground,” Noldus said. “But when they put the frequencies up for auction and anyone could get a frequency if they had the money, it opened the door for us in a big way. Lots of idiots bought frequencies and started radio stations that ultimately didn’t make any money. So that’s why we could go around and scoop them all up.”

If a local station was unwilling to sell, Energy would buy up as many frequencies as possible in the region, start broadcasting their network stations, and squeeze the local station into selling. Buying up frequencies was a novel strategy: most of the major networks were content with owning one frequency per station, and morally objected to forking out every time a new one was released. But early on, Joyce had realised that under the new regime, frequencies were key. “I’d done the math,” he said. “If you didn’t own the frequencies you were buggered. The trick was to own as many frequencies as you can, and that would give you an even chance of getting enough market share to actually make money.” Joyce bought half of Rotorua’s frequencies for a combined $45,000 and – applying the lesson that The Rock had taught them in New Plymouth – bought $300,000 worth of LPFMs in Palmerston North, frequencies that the city’s commercial mainstay, 2XS, had believed worthless and ignored. Soon enough, 2XS – their sparring partners from a decade earlier – were forced to sell up.

By 1998, Energy owned stations in New Plymouth, Hamilton, Tauranga, Rotorua, Taupo, Napier, Hastings, Whanganui, Palmerston North and the Manawatu. That year, The Rock and The Edge relocated to Auckland, and began networking across the North Island. In 1999 Energy merged with Radio Otago, growing to over 20 stations nationwide, and rebranding as RadioWorks. By now it was the largest privately-owned network in the country, worth almost $100 million.

RadioWorks inherited Joyce’s business strategy: take over struggling local stations, overhaul their programming, and supplement the local outfit with network content. The ultimate aim was to have five stations in any given market – the local station, plus the four network stations of The Edge, The Rock, Solid Gold and Pacific – broadcasting across as many frequencies as possible. The local heritage station would remain the star attraction and the main money-earner, targeting the lucrative family demographic of 25 to 49 year olds. However, the plan would require those stations to shift their brand to more community-based, family-oriented content.

In this respect, Joyce encountered unexpected opposition from the local stations themselves. Many of the heritage stations – Energy, 2XS, Dunedin’s 4XO – had started out as the Top 40 outfits of their area. At these stations were staff who had wanted to work in edgy, youth radio, and now found themselves taking a big, stodgy turn toward community broadcasting. “The staff wanted to be at the cutting edge,” Joyce said. “So they were the biggest stumbling blocks in many ways because they just couldn’t shift the brand.”

This resistance made Joyce by turns exasperated and indignant. “The irony of it was that I was the guy that started Energy FM, and I knew the heritage better than anyone else,” he said. “But there were younger people who’d only worked there for a couple of years and had this thing in their head about what Energy FM was about.” He began to use The Edge as a battering ram to force Energy and the other heritage stations – stations in his own network – to change; with The Edge taking a big chunk of the youth market, the stations’ revenue would dry up unless they acceded to their new role.

Joyce the programmer, the man who spent the summer of 84-85 trying to stop Jeremy Corbett and Quentin Bright from playing all those weird songs, had shaped the market in his image. Between the heritage stations’ shift away from music, and the introduction of multiple tightly-controlled network stations, there was no space left in the cramped New Zealand market for what Energy FM had originally been: a somewhat alternative station that met halfway between mass tastes and the sensibilities of its presenters. In other words, if every station was set up to pander, who was left to push the boundaries?

In truth, something like this was always likely to happen. In their book The Great New Zealand Radio Experiment (2005), Gerard Duignan and Morris Shanahan argue that a combination of deregulation, the explosion in number of privately owned stations and frequencies, and the delayed effects of the ‘87 stock market crash created a powerful centripetal force in the New Zealand radio market that pushed stations toward consolidated ownership and economies of scale. The impact on the music industry was huge.

Various board members had tried to call; Joyce rang them back and received the news: RadioWorks was being raided.

Because, as Duignan and Shanahan point out, the dominant strategy was now to network “mainly generic products” into multiple markets, local musicians had to adopt more mainstream sounds to get played. Once thriving local scenes fell into obscurity, notably in Christchurch and Dunedin. As any Dunedin music fan can tell you, the Dunedin Sound never really went away – it just disappeared from the airwaves, anathema to, in the authors’ words, “a consolidated, conservative, reactive commercial radio climate that is only proactive in maintaining uniformity”.

This shift did not go unnoticed at the time: 2XS’s former station manager Larry Summerville, by then at More FM, used to complain that RadioWorks was turning New Zealand radio into The Warehouse (non-Kiwi readers, think Walmart). Joyce, though, liked to think of it as a multiplex. To his detractors, this is Joyce in a nutshell – countering a crass capitalist metaphor with a crass capitalist metaphor. But Joyce has always owned who he is: a businessman and an entertainer, not a tastemaker. And where Summerville saw a soulless barn overstuffed with tacky crap, Joyce saw a stable of sleek big-hitters, each carefully calibrated to thrill.

*

Joyce was at the New Zealand Broadcasting School in Christchurch in May 2000, interviewing potential new recruits, when his phone went mental. Various board members had tried to call; he rang them back and received the news: RadioWorks was being raided.

Joyce had long known that there was “one more deal to be done” – a merger with long-time rivals More FM. By the end of the nineties, More FM was a relatively small group of stations in a market now dominated by networks; they lacked RadioWorks’ economies of scale, and Joyce was ready to push into Christchurch and “cause very big problems for them”. Rather than wait for The Edge to take them out, More FM’s Canadian owners decided to strike first.

In the initial raid, CanWest bought seventy-two per cent of RadioWorks at $8.25 a share. Don Raine and Peter Noldus, the last relics of the original Energy FM, both sold up, and Noldus moved to Thailand. Joyce stuck around. He wanted to secure a better price for the remaining shareholders, including himself, but it was an emotionally draining experience.

He frequently clashed with the Canadians, and was contemptuous of what he saw as their “conquering hero” approach to the takeover. As far as he was concerned, the Canadians hadn’t done anything admirable; they’d lost the ground battle, and responded with an airstrike. After a year, he’d negotiated a deal – “we both felt slightly screwed, so it was probably a fair price” – and he sold his own stake for $9.35 a share, pocketing $NZ6 million.

CanWest would go on to merge RadioWorks with TV3 in 2004, forming the MediaWorks empire. But for Joyce, the raid was an odd, hollow full stop. He bought a new car and drove it to Wellington for a friend’s wedding. On the road, travelling through the regions where he’d made his empire, he realised it was time to let go. Time to start a family. Time to take up jogging. He set his retirement for the day before his 38th birthday, and made a point of visiting all twenty-two of his stations over the final few weeks to say goodbye. He had a bad habit of shouting everyone Drambuie; by the end he was sick to death of the stuff.

In Rotorua two of the jocks, Gary Watling and Deano Lonergan, invited him on air as a guest co-host. It was the first time Joyce had presented a show since moving upstairs in 1994. “I hadn’t been on air for so long,” he said. “I mean it was very indulgent, and bloody generous of them to do it, but it felt great. And I remember feeling, ‘shit, well, that was what it was all about’.”

A sentimental ending, perhaps, but a slightly disingenuous one. When Joyce recounted that anecdote to Gerard Duignan, he implied he had picked it mainly for its narrative symmetry. It rang false then, as it does now.

One man who has largely been overlooked in all of this is Don Raine. Raine, according to Andi Brotherston, is “one of the biggest introverts to ever work in the radio industry. He’s not a recluse but he’s as close you can get to being a recluse without being one.” Yet, like so many extroverts, Raine was drawn inexorably to the studio.

“Radio is a funny thing,” Brotherston says. “When the door of the studio closes, it becomes your own bubble in the time you’re in there. And so for people who are shy but like to perform it feels like you’re all on your own in the world. You can almost convince yourself that nobody else is listening.”

But that wasn’t Joyce. In fact, for almost his entire career, Joyce fiercely resisted any romantic notion that the studio could be viewed in isolation. What he seemed to love above all was the puzzle: how everything from the studio, the sales, the music, the laws, to the listeners, all interacted. How to leverage those parts to create something new. “How,” as he said, “to make money in an industry where the rules had changed.” All he ever wanted, really, was complete control, and time to fit those pieces together.