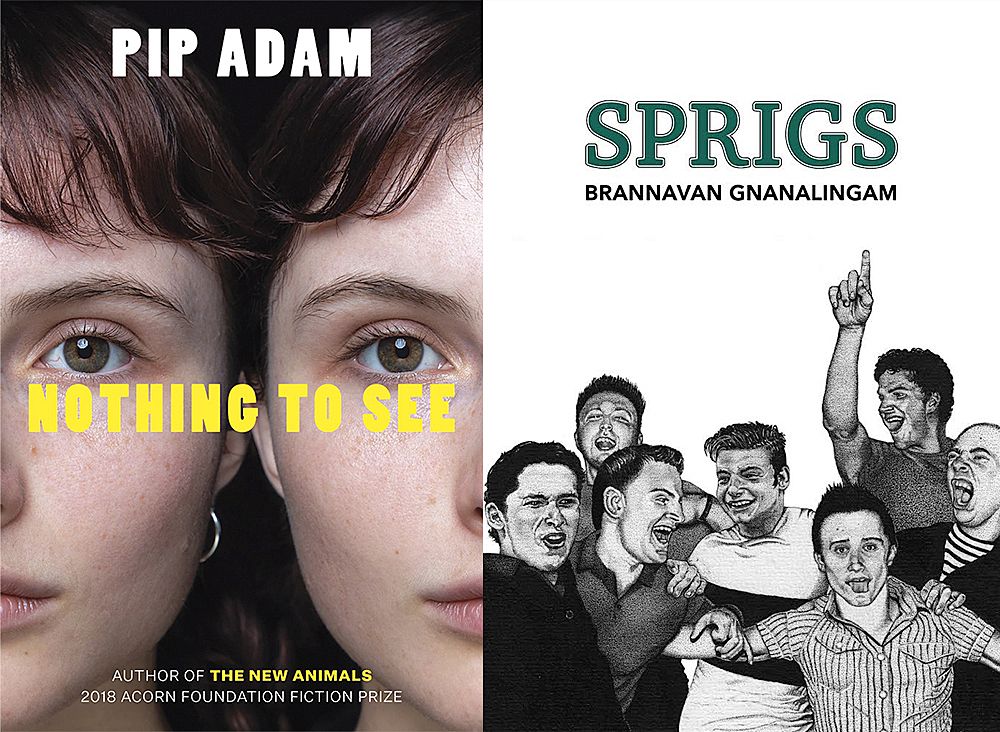

Survival: An interview with Pip Adam and Brannavan Gnanalingam

Novelists Pip Adam and Brannavan Gnanalingam discuss writing about trauma and how the narratives we tell ourselves compare to reality.

Are you afraid of heights? Reading Pip Adam’s new novel, Nothing To See, I often pictured myself walking along a high wall: there’s plenty of space and it’s not hard – but you can’t let yourself look down. That’s when you fall.

That’s what the journey of recovery feels like for Peggy and Greta, the book’s main character – or should I say characters? – as they recover and rebuild from alcoholism and the trauma of violence and rape. As the book leaps ahead in 12-year blocks, we spend time with Peggy and Greta as two bodies, then one – Margaret – and then two again. What emerges is a story about the ongoing work – but also the joy – involved in choosing to survive.

Priya, the central character in Brannavan Gnanalingam’s latest book, Sprigs, also chooses survival. For much of the book, after an ‘incident’ at an after-match party, Priya’s perspective is eclipsed by the swirl of events, narratives and counter-narratives of the boys, teachers, parents and other students involved. What follows and what the book gives us is not so much a reclaiming of agency – nothing that easy or jubilant. But it does show us about defiance.

I want to say these are both important books – because they are, they are books we need. But it does them a disservice if it implies they are leaden, or worthy – they are not. I was absorbed into the worlds of both books with a totality that testifies to authors well into their writing careers and in complete control of their craft. As I was reading Nothing to See, I felt I was reading Pip’s best work ever – as if her earlier books enabled this one to be written.

“There was a sense of freedom that, maybe, Nothing to See wouldn’t get published,” says Pip, “that maybe I could write it for me and in private. I wonder if that comes from having other books published; that desperation to be published had gone a long time ago. I’ve talked about the [Acorn Foundation Fiction] prize kind of giving me confidence. But what it also gave me was kind of a feeling that this book was not going to be a very good book. Like when a band peaks with an album. It felt like the pressure was off a bit.”

Once it’s being read, it’s being written again. I detach myself from that.

“There’s no way I could have written Sprigs as my first book,” says Brannavan. “I wouldn’t have been able to balance all of the things that I was trying to do. Writing is one of those things where you just get better the more you do it. It’s not like music, where often the energy and the sheer risk-taking that people have at the start means they do amazing stuff right from the outset. You have to balance the excitement and energy you get when starting out with the sense of control. I think I’ve got more of that now than I did.”

“I totally agree about getting better,” says Pip. “There’s no way I would have had the language to write Nothing To See as a first or second book.”

Both authors felt a sense of privacy while writing – followed by a shock of exposure when the book was published. “I think it was about three weeks after it was launched,” Pip recalls, “I just got this wave of ‘Oh, fuck… What have you done?’ But I can just get out of the way. Once it’s being read, it’s being written again. I detach myself from that.”

“I felt like I had to do that as a kind of defence mechanism,” says Brannavan. “It’s clearly a book about trauma and in part based on my trauma, but I also didn't want to just write about my trauma, because I didn’t want that experience of having to talk about it and relive it over and over again in the process of editing and interviews. So I added that distance.”

*

Trauma, alcohol and rape – the themes the books share – are hard to talk about. Were there things the authors worried about?

“There are discursive frameworks around sexual violence and rape,” says Brannavan, “and the moment you kind of engage within those frameworks, you’ll be read within those contexts. So you kind of worry, am I adding anything to the discourse? Am I taking stuff away? What kind of responsibility do I have, trying to tell these stories?

If someone criticised me for it, I don’t think I’d have a response to it, except that I’m sorry

“I didn’t write about myself in part because I was so worried – unfairly, I suspect – about being read as solipsistic. I used a different character’s narrative to hide, and to kind of disengage a little bit.

“So my fear was around engaging with the subject matter: have I fallen into clichés? I did a lot of research and thinking about discursive frameworks.”

Brannavan started writing and thinking about Sprigs in 2016 – three years after the Roast Busters were in the media.

“Now, you would think there’d be a different take on it from the media,” says Brannavan. “You’d hope.”

Pip reveals that in earlier drafts, her book was called Care. “I’m really interested in how you can build consent into the fiction – the reader’s consent. There’s one particular thing that happens in the book, and I’ve got this fantasy that I might break into bookshops at night with a vivid maker and redact it out of some copies, because I don’t feel there’s any consent built up to that event. My main concern was how to write about it without re-traumatising.

“I learned heaps from watching [the television series] I May Destroy You that I might have done differently in the book.

“We use words like ‘survivor’, but I am really interested in how we rebuild – and I don’t even like that idea of rebuilding lives after rape – but how do we carry on?”

Brannavan shares some similar concerns. “I worry that I have created a book that re-traumatises. And if someone criticised me for it, I don’t think I’d have a response to it, except that I’m sorry if it does.

“I became kind of obsessed with this idea of what is the nature of testimony? And what does testimony mean within a framework that is completely hostile to victims and survivors?”

Pip says that as a reader she appreciated that right at the start of Sprigs – there is a content warning.

“I think content warnings are really important. I could see what I was in for and could make a decision about where I read it, when I read it, whether I read it with other people in the house.”

*

Omission – what each author chose not to write – feels just as important as what they did. In both stories, the most violent events are not directly described. Were the authors protecting themselves, or protecting the reader? At what point does violence become gratuitous or re-traumatising? We don’t actually have to live through the most violent events with the characters, so the stories are more about, “well then what?”

“I was always very clear that I wasn’t going to depict the violence itself,” Brannavan tells us. “My background is film and it’s such a cliché for a lot of films – male art-film directors – to just throw in a gratuitous rape scene. It’s a horrible thing as a writer and it’s a horrible thing as a reader, and for the most part it’s completely unnecessary. I just didn’t want to. I was more interested in the consequences.”

There are these structural things around [rape], and they’re often around protecting the powerful

Pip says the first few drafts of Nothing To See did contain a long, violent scene. “A horrific, step-by-step description of a sexual assault by multiple people. But I recently did a writing course with Alexander Chee, and he was talking about this idea of not using the writing as the first place where I tell the story.

“Part of my problem was thinking, if I say a word to describe something, will people go back to those connotations that they’ve got from rape culture, and from movies? Am I better off showing it, bit by bit and in great detail? Then I realised that even by doing that, I’m starting to reframe it. I wanted to make it work for narrative reasons rather than emotional or truth testimony reasons, so I took it out.

“In I May Destroy You, life goes on, you know. Sometimes people have a problem with people who have suffered rape still wanting sex. There are all these structural things around [rape], and they’re often around protecting the patriarchy, protecting the powerful.”

“I’m most of the way through,” says Brannavan. “Michaela Coel is an utter genius.”

“She deserves everything,” agrees Pip.

*

I want to talk about goodness.

In Nothing to See, I never questioned that Peggy and Greta were good. Despite being separate, there was a wholeness to them, a kind of harmony: they keep each other honest. And just little things – even Peggy and Greta’s vegetarian diet feels like another clue that they are a good person. But later on, when Margaret starts to work for a social media company, using people’s data for political purposes, she becomes more morally complicated. Heidi and Dell, on the other hand, feel like they’re constantly in a grey area, constantly switching. I couldn’t help but think of that cliché of the angel and devil on the shoulder.

In Sprigs, goodness is radiated out through the cast of characters: with Priya at the heart of the novel – her goodness feels very strong; in those who surround and care for her – there’s goodness, but it’s flawed; right through to the remorseless young men and their slimy fathers, who absolutely lack any sense of morality. I am interested to what extent the authors were thinking about goodness, or whether that whole idea is just too easy.

“A common theme in both of our writing is compromise – how much people compromise in order to basically just survive,” says Brannavan.

I was interested in examining whether non-white people get second chances, either as victims or perpetrators

“When people are suffering from trauma or an incident or something, it’s academic to whoever is trying to help, unfortunately. They can definitely help – and clearly it’s needed – but there is always going to be a distance between what the victim had gone through and what anyone else can do. That, for me, complicates goodness.”

*

Perhaps more interesting to consider is blame – and on the flip side of that, sympathy. In Sprigs, despite Richie being one of the rapists I inevitably felt myself feeling sympathetic towards him, and nervous that he was going to be scapegoated because of his vulnerability, racially and socially. I really thought that the book was going to go down that route of him being demonised and tuned into the ringleader. It didn’t, but I was interested in the process of feeling that sympathy for the character, despite what he’d done.

“I was trying to work through the way we talk about sexual violence,” says Brannavan. “In mass media, rapists are often the people hiding in the bushes, or the strangers. So there’s a real tension between humanising the rapists, but also showing them to be ordinary teenage boys, or ordinary men, who are capable of committing this sort of violence.

“I was also interested in examining whether non-white people get second chances, either as victims or perpetrators. I wanted to see whether discursive frameworks structure or pre-determine how they’ll be treated in the aftermath.”

The way the schools handle the incident – the scapegoating and the ass covering – I was right there, believing everything

In Nothing To See, the whole story unfolds after Peggy and Greta get a second chance.

“Peggy and Greta sort of hit a point where everything they’ve done in the past kind of hits them,” says Pip. “The desire is to be good from then on. But being good changes, depending on society. It’s so Bertolt Brecht, isn’t it – is it okay to steal a loaf of bread if you’ve got a starving family?

“One way to re-enter a society that you haven’t been a part of is to change your wardrobe, change your language, stop swearing. And I think goodness is a gendered thing, as well. When you look at depictions of non-binary-conforming people, there’s a way to act that is seen by the mainstream as good. Even for people with a disability, there’s a way to be good.”

Pip points to a moment in Sprigs, when there’s an assembly and someone calls out “rapist” just as Pritchard, the head boy, goes onto the stage. “These men have standing and they are being called up to be celebrated. Then to have that word associated with them – I just had to sort of stop for a minute and think ‘fuck, that’s quite full on’.”

*

One of the most successful aspects of Sprigs is the depiction of the way that the schools handle the incident – the scapegoating and the ass covering. I was right there, believing everything that went on.

“I’ve always been fascinated by the difference between the narratives we tell ourselves and the reality of the situation,” Brannavan says. “I’ve always been obsessed with PR. The ‘Vulture’ character – this is the third book of mine that he’s appeared in. I love writing him, and I love writing his monologues because I get to indulge my obsessions with the way people sell themselves, the way institutions try to sell themselves and the way reputations operate.

“I started working during the Global Financial Crisis. I was watching companies deal with the fact that a lot of them had misled investors and had sold a reality that wasn’t real. And when they collapsed, they pretended that no, no, there were other causes.”

There are clear parallels between this aspect of Sprigs, and the part in Nothing To See where the social media company that Margaret works for is exposed, and tries to pass the blame to its contractors.

“PR seems like storytelling to me,” says Pip. “I’ve never worked in PR, but so much of it is narrative, it really frightens me. It’s stupid because this is the way the world’s always been, but I think I’m just waking up to it – that often we can say things and they become true.

“My obsession is kind of around Facebook and Zuckerberg and all of that strange stuff. There are all these companies that are run completely by future capital – they’re not making any money – what are they doing? They don’t want to call themselves media companies. I do feel like we’re living in a simulation. I just increasingly don’t know what to believe.”

That part of Nothing To See echoes a theme that runs throughout the book, about seeing but ignoring. We have to face things that make no sense and just kind of keep on living as if they do. The double woman is one of those things: when it makes people uncomfortable, they just ignore it.

We’re virtually interpreting reality the way that it suits us

Pip draws a parallel to the video of the rape in Sprigs. What seems like incontrovertible evidence is dismissed and questioned by several characters. “That’s where it felt a lot like Roast Busters to me. Like, how is this not enough?

“We’re virtually interpreting reality the way that it suits us. I read this terrifying study that says people believe things that align with what they already believe. They don’t believe things based on facts – they believe things in line with what they believe will be best for them.”

“I found it interesting in your book,” Brannavan tells Pip, ”the way that everything felt automated around Peggy and Greta, like a kind of bureaucratic Ruth Richardson nightmare. Facebook and Cambridge Analytica have kind of replaced that, although it’s obviously still there in the way that Work and Income treat people. There’s a real sense of people getting more and more trapped by these processes and frameworks.”

The last section of Sprigs is called ‘The Trial’ – but there is no trial. Central character Priya goes through the mental exercise of imagining one; she’s smart, she knows what a trial would involve, and mentally, she decides to take a different path.

*

At the beginning of Sprigs, there is a constantly shifting perspective. It almost feels like a movie, with each of the characters in focus, in turn. But for a while after the incident, Priya almost disappears from the book; her perspective escapes our view. It all just becomes hearsay, and Priya herself has no say in the way it unfolds. It’s a smart way of reflecting the way survivors are silenced and their perspectives sidelined. But as a reader I was grateful that, in the last section, we do return to her point of view.

“The structure I was working to was this idea of object versus subject,” says Brannavan. “The way that sexual violence is often talked about, and the way that institutions that deal with sexual violence also do that – whether it’s the media or the criminal justice system – you’re an object first, before you become a subject. So I replicated that in the novel, with the idea that no matter what Priya might say, she’s always going to be constituted within the framework that’s been created around her of who she is. So she’s kind of doomed. The testimony is going to be hard to break out of that, because of the structure that’s in place to basically deny her a voice, or require her to tell her story on someone else’s terms. Not her terms.”

I get the sense that the violence couldn’t happen without the rugby

The pace in Sprigs accelerates; after the incident everyone loses control, time speeds up and things are sort of spiralling.

“There are two almost competing models that I used to create the pace,” Brannavan tells us. “The first is that I love action cinema. The best action filmmakers – like John Woo and Spielberg – spend a little bit more time constructing the ‘space’ of the scene than most other action film directors. You always know where you are within the scene before they let the action go. That almost creates a faster action but also a more coherent sense of action.

“Part 1 – yes, I’m aware that it’s a rugby scene and it goes for quite a while, but I felt like I wouldn’t have been able to get the pace that I got in Part 3 without having set up all of those characters.

“[The second is] the model that Balzac, the French writer, uses. He spends a lot more time setting up his characters and setting up the framework, and then he lets the narrative go. Then you can use things like inevitability, you can use things like anger – you can use emotions to create the pace.”

“I really loved the rugby,” says Pip. “It builds the structures, as well. In my mind I get the sense that the violence couldn’t happen without the rugby; there’s some kind of power dynamic that’s built up in the rugby that makes the violence possible at the party. It’s almost like winding up a spring.”

A team is the ultimate formal structure in which everyone must belong – and everyone must conform. Extreme loyalty.

“Loyalty,” agrees Brannavan, “and doing it for the boys, doing it for the team. That ignores the internal differences between the characters; like the fact that most of the characters will be rich, well-off kids, who have the privileges to escape things, versus Richie or Tim being on the outer already.

“I always think sport’s an interesting space where classes come together,” observes Pip.

“That was actually one of the key reasons for sport under the Victorian era, to kind of help create a conforming society,” Brannavan tells us. “You’re following rules, and there’s a kind of mateship that you get from it. Arguably rugby took on a bigger hold in New Zealand as a way of effacing some of the class differences. But it was a colonising mission – that’s why the British pushed sport hard, and why we all played British sports like football and cricket and rugby.”

But it’s also true that, in Sprigs, class runs deeper in the end. “It feels like a failed utopia,” says Pip, “because Richie is never allowed to forget his place.”

There’s a certain type of language used for Conrad Smith, versus Ma’a Nonu, who’s kind of portrayed as the physical bulldozer

Brannavan’s writing of Richie and his teammates also provides a critical view of how bodies in colour are read in sport.

“My favourite example is Ma’a Nonu and Conrad Smith,” says Brannavan. “Every single time Smith is mentioned in any article, it’s mentioned that he’s a lawyer – smart, brainy, incisive. There’s a certain type of language used for Conrad Smith as a Pākehā footballer, versus Ma’a Nonu, who’s kind of portrayed as the physical bulldozer – the language that’s used is so racially coded, and so obvious – when they’re both just really good footballers. The way language was used to describe them is really coded, and it’s awful.”

Although there aren’t often physical descriptions of individual characters in Sprigs, certain details about their bodies and the way they interact speak volumes. The way the players hug – without their genitals getting too close. The way Priya’s injuries are described: that repetition of “It hurt. It hurt.” The language is simple, but direct.

In Nothing To See, I don’t come away with a strong sense of Peggy and Greta’s features or how attractive they consider themselves to be. But certain details of their clothes – their floral dresses – and the ways they move around each other, are vivid.

“I find writing bodies hard because a lot of the hardest things about living, for me, lie in my body,” explains Pip. “Especially around whakapapa and identity. Not knowing where this body comes from. I’m like the darkest child in our family. And there were and are some complicated things around that. A lot of those problematic things happen in my body, so I think that I have a very vague understanding of my body. I’m never sure where it ends and where it begins – I’m quite clumsy.

“I think of whakapapa as a place to stand, tell the story from. I never really feel like I have that – I’m unsure of where I stand and how to tell that story.”

*

I’m interested in the choices about specificity that have been made in both books. Sprigs is very specifically Wellington and yet pretty much all of the institutions and people have fictitious names – except for some references to Sir John Key, which make me smile. The setting for Nothing to See is never named, although as a Wellington reader I felt like I recognise certain places in the book.

“I was thinking of 2666 [the novel by Roberto Bolaño],” says Pip. “That idea that if you laid the imaginary city over the real city, the streets would all be the same but they’re named differently.

“To me, the whole book does take place in a simulation, and that was why I decided not to name Wellington or Christchurch.”

“I was a kid in the 90s,” says Brannavan. “The Simpsons was my first big cultural touchstone. The idea that you could create satire and a world using recognisable stuff but also doing whatever you want because you’re trying to make a point was something I’ve always been interested in. St Luke’s is an amalgamation of a number of schools that I’m aware of and stories that I’ve heard.

“In satire you almost want no one to recognise themselves in it or you want everyone to recognise themselves in it. You can’t have just the target recognise themselves, because then it’s too obvious but then also you can’t really make the critical point you’re trying to make.”

It’s interesting to me that Brannavan refers to Sprigs as satire. I recognise the book’s critical lens on society, and yet, as awful as many of the men are, with the exception of The Vulture there is little of the exaggeration or crudeness I often associate with satire as a genre. Sprigs feels profoundly – and damningly – like realism.

I also really enjoyed writing the sex. I did a lot of research.

In Nothing To See, meanwhile, Pip Adam applies realism to a fundamentally surreal premise.

“I have always loved the way you shift genres within an ordinary or banal framework, and just how unsettling and brilliant that is to a reader,” Brannavan tells Pip. “It’s almost like you start off with social realism, and the swerve is utterly fascinating.”

“The only thing I understand about narrative structure is the twist,” says Pip. “I went for a long time without reading – pretty much from being 8 to 24, I didn’t really read – but one of the first books I read was Fight Club. And I was like “Aha, I understand how to write a twist; you withhold information.” I think that because that’s one of the few things that I understand, I rely on it a little too much.”

If there’s a twist in Nothing To See, it’s not a straightforward one. The mysteries of the tamagotchi phone that receives ghostly messages are never really laid bare. Instead, what we get is a kind of unravelling. A sense of emotional ground shifting. And reminders of the ongoing work – but also joy – when we choose to survive.

And although both books deal with such serious things, there are moments of real joy. In Nothing To See, it was the quiche – how proud Peggy and Greta are when they master the recipe.

“I really love the quiche,” says Pip. It’s quite an autobiographical part of the book, as well. That amazement. Food had been such a horrific part of my life up until then, and then it’s suddenly – ‘What? This is something that can happen in my house? We can eat? This seems bonkers!’

“I also really enjoyed writing the sex. I did a lot of research – not that kind of research! I read a lot of books that were explicit. Often in my books, [sex] is like a ‘beep’ – a moment of silence in the book. I find it really challenging.”

In Sprigs, the scene where Priya’s mother, Amma, throws a glass of water on Priya’s school principal is the most incredibly triumphant moment. I wanted to do a fist-pump and give Amma a hug.

“I found the glass scene fun to write,” says Brannavan. “And also the visit from Appamma [Priya’s grandmother]. The build-up has quite gentle humour that probably only Tamil people might get. Like the phone call – honestly, you listen to [Tamil] people talking and they’ll say hello about five times, and then there’ll be very little said.

“Hopefully there’s a bit of an emotional payoff with her visit, too. Because it was such a dark book to write, I held onto those little moments personally, as a writer, because I wanted to feel some hope and light and kindness.”

“It’s such a political move as well,” agrees Pip. “Including joy in people’s lives.”

Nothing to See (Victoria University Press) and Sprigs (Lawrence & Gibson)

Nothing to See is published by Victoria University Press. Sprigs is published by Lawrence & Gibson.

Feature image: Pip Adam (photo: Ebony Lamb) and Brannavan Gnanalingam (photo: Lucy Li).