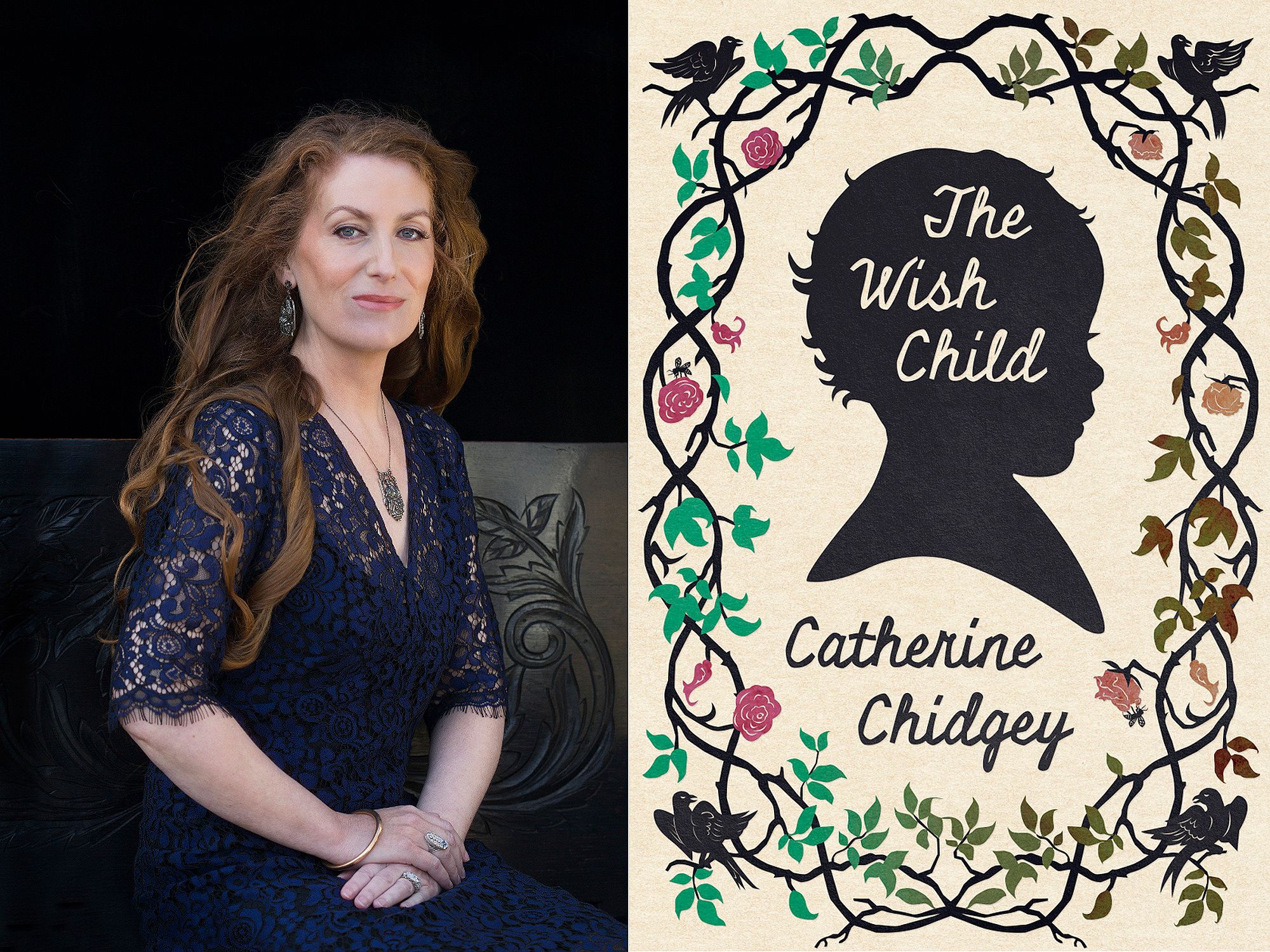

Fiction: The Wish Child

Read an excerpt from Catherine Chidgey's new novel, The Wish Child, which the publisher describes as 'a profound meditation on the wreckage caused by a corrupt ideology, on the resilience of the human spirit, and on crimes that cannot be undone.'

Launched in Hamilton on 8 November, 2016, The Wish Child follows two children living in Germany during the Second World War. Chidgey’s previous novels are In a Fishbone Church (1998), Golden Deeds (2000), and The Transformation (2003). Some of her honours include Best First Book at the New Zealand Book Awards and at the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize (South East Asia and South Pacific), a Betty Trask Award (UK), the BNZ Katherine Mansfield Award, and a longlisting for the Orange Prize. Photo of Catherine by Fiona Pardington.

22 Nov 2016 update: The Wish Child is on the Ockham Book Award longlist for the Acorn Foundation Fiction prize; the short list is scheduled to be announced in March 2017.

September 1941

Berlin

‘What do you do at work?’ Sieglinde asked her father, swinging his hand in hers as they set out along Kantstrasse. They were visiting the zoo, a treat for Jürgen’s birthday, and Mutti and the boys had gone on ahead. Sieglinde was wearing the little brooch made from Vati’s baby teeth, and every so often it caught on her braid and made Vati laugh.

‘Stop biting me!’ she said.

‘Delicious,’ he said.

They turned into Joachimsthalerstrasse and soon they could see Mutti and Jürgen and Kurt waiting at the Lion Gate, which led not to the lions but the elephants. Against the bright sky to the north the flak tower rose like a castle, and it was full of paintings and sculptures and priceless objects – the head of Nefertiti, the altar of Zeus – and it held an entire hospital, and plenty of air, and it could not be bombed.

‘But what is your job?’ she asked again.

‘I make things safe,’ said Vati.

‘What sorts of things?’

‘Just things.’

‘Buildings? Bomb shelters?’

‘Not those sorts of things.’

‘Sharp things, then. Razorblades. Broken glass.’

‘It’s not like that, Siggi.’

‘Ropes on pianos, for all the people moving out of their apartments.’

Vati laughed again.

‘The water. The sky. Air. Conversations!’

‘Don’t be silly. It’s not like that.’

‘What is it like, then?’

‘I take dangerous things away, so they won’t be dangerous any more.’

‘Oh,’ said Sieglinde, and she thought: polio, lit windows, neighbours? She didn’t ask, though; she supposed this was another question nobody would answer. Vati would not tell her what he did at work, just as Mutti would not tell her why Dr Rosenberg was no longer their doctor, why a different man sat at his desk, tapping Sieglinde’s bones and counting her heartbeats. ‘What if your building is bombed?’ she asked instead.

‘Impossible,’ said Vati. ‘They’ve covered it up so it looks like a forest, and put up false ones somewhere else. Isn’t that clever?’

Sieglinde nodded; yes, it was very clever indeed.

They had caught up to Mutti and the boys now, and Vati bought their tickets and they filed through the gate. First they stopped to watch the elephants in their enclosure, which wasn’t enclosed at all, because there were no walls, just a ring of spikes that would hurt the elephants’ feet if they tried to walk across them to where the people stood. The tree-trunks were wrapped in spikes too, because otherwise the elephants would eat the bark and the trees would die. There must have been a time for every elephant, though, Sieglinde thought, when it tried to eat the bark, or cross the spikes – mustn’t there? Before it learned that it could not? She wanted to ask Vati, but already he and Mutti and the boys were moving on, because Titine the chimpanzee was riding her bicycle, which was not to be missed. The chimpanzees could smoke cigarettes and sit at tables and eat with spoons, just like human beings, and Jürgen said he would like to have one for a pet, but Vati said that would not be natural.

‘You know,’ said Mutti, ‘when I was a little girl, they used to put Indians on display. Indians, and sometimes Eskimos, and African warriors with bones through their noses.’

‘Can we see them?’ said Jürgen. ‘Do they have spears? And poisonous darts?’

‘Oh no, they don’t display them any more,’ said Mutti.

When they reached the lions Vati said they should have their photo taken, because there were three lion cubs and three children, and so they waited while another family had their turn, and everyone laughed when the French zookeeper put a cub into the other family’s pram, right in with the baby, and Sieglinde tugged Mutti’s sleeve and said, ‘What if they take the baby lion home, and leave the baby boy here?’ but Mutti did not answer her, because she was talking to the other Mutti and saying, ‘Six children, my goodness, what a busy life you must have.’

Then it was the Heilmanns’ turn, and they sat on the bench and the French zookeeper put the cubs on their laps, and Kurt’s cub kept trying to bite his nose and even though the French zookeeper said he was just playing, Kurt would not stop crying, and the photo was ruined.

The bear looked bored. It sat behind its bars and stared at nothing, not even caring about all the people who had come to see it, which was quite rude.

‘I don’t think he likes it here,’ said Jürgen.

‘He does look gloomy,’ said Sieglinde.

The people stood before the enclosure and waited for the bear to do something: to show its teeth, to growl, to stand on its hind legs like the one in the brochure. A man looked at his watch. A young soldier roared at the bear, but still it did not react. Behind a thousand bars, no world.

‘I think it’s broken,’ said the soldier.

‘Boken,’ said Kurt, trying out the word in his mouth.

‘Is he broken?’ said Jürgen, looking as if he might cry.

‘Of course not, of course not, what a thing to say,’ said Mutti, glaring.

‘But he does seem unhappy,’ said Sieglinde.

‘I think he’s just tired,’ said Mutti. ‘Why would he be unhappy? He has everything he could possibly want.’

‘No one is kinder to animals than we are,’ said Vati. ‘In America they experiment on monkeys, and the French boil their lobsters alive –’

‘Thank you, Gottlieb,’ said Mutti.

‘Well. My point is, we look after our animals,’ said Vati. ‘Even the wolf is protected.’*

Sieglinde says, ‘Mutti, the apartment is bigger.’

I watch through the window, I sit with the crow. Do the dead take the form of birds? We wait and we listen.

Mutti says, ‘Nonsense, Siggi. You shouldn’t make these things up.’ She has her powder compact open and is looking in its secret mirror, dabbing her forehead and her chin with the little pad she keeps in there to cover any blemishes.

Sieglinde says, ‘But the living room is longer. Before, if I sat on the sofa and held out my arms, Kurt could walk all the way from the far wall in ten steps.’ (And when he reached his sister he would squeal as she swung him onto her knee and kissed his nose, and he knew he had done something good.) ‘Now it’s fifteen.’

‘Children are like that,’ says Mutti. ‘One day they can buckle their own shoes, the next day their Mutti has to do it for them again. One day they can feed themselves, the next day they’re rubbing stewed apple through their hair like a monkey and their Mutti must clean them up.’ Dab, dab, goes the little pad; just enough to look natural. The crow pecks at the window, its beak striking the glass like hail.

‘Monkeys eat bananas,’ says Sieglinde.

‘So they do,’ says Mutti. ‘You’re a clever girl, Siggi. No more stories, now.’ In her secret mirror the crow tilts its head.*

The Heilmanns are happy in their marriage. Look at them: they are a suitable match, a good example; no crooked bones, no deficits, no shadows in the blood. Yes, they are happy, people say they are happy, even though Brigitte’s nerves are bad whenever there is a raid. It’s just leaflet drops, Gottlieb tells her. Nuisance raiding. But she flinches at any loud noise, any sudden movement; around her Gottlieb feels he is walking underwater. Still, when he considers other wives – the bad teeth and double chins, the veins and the moles, the poorly designed torsos – he counts his blessings. Brigitte does not wear trousers or lipstick or heels; she does not curl or starve or dye. She was just eighteen when they met; a respectable girl from a respectable family in Celle; as malleable as wax. She answered his newspaper notice, and there is no shame in that; lots of decent Germans advertise for the right sort of spouse. Besides, nobody remembers it now, and if they do, it is never mentioned.

‘England,’ he reminds her. ‘We are fighting the English. We are not at war with Britain.’

‘Of course we are,’ she says.

‘Still, we say we are at war with the English. That is what we say.’

‘But everybody knows we mean Britain.’

‘Yes.’

‘Then why don’t we say it?’

‘Because we are fighting an island, not an empire. When we have won we’ll say it was an empire, but for now it is an island. You must listen.’*

Here is Gottlieb Heilmann on a Monday morning, arriving ten minutes early to his job. See how he hangs his hat and coat on the hook that bears his name, how he places his briefcase at the right-hand side of his desk, sits down at his typewriter and removes its cover. The green carapace unclicks, the blank paper and the carbon paper twist into the machine and the letters raise their inky arms. Choice, he types. Opinion. Love. His office is one of dozens in the Division – perhaps hundreds; he does not know – but his name is painted on the frosted-glass door, and that is how he knows he is in the right place and has not taken a wrong turn, for the building is the sort of building that can make a man lose his bearings. So here he is, sitting behind the frosted-glass door labelled Heilmann, and from inside the office the name is backwards and makes no sense and is not his name, and the letters are painted in gold and shadowed in black to give them depth, the illusion of depth, like letters carved into a gravestone. And I say office because everybody says office, but behind the frosted-glass door the walls reach neither the ceiling nor the floor, and they are set with frosted glass too, winter windows that never clear, and above them drift the sighs and whispers of Gottlieb’s colleagues, and through them he can make out the hazy shapes of men like himself, but not their faces (never their faces).

Gottlieb finds it curious to think he could not even type when he began working for the Division in 1939. It was his skill with scissors and blades that secured him the job, he discovered; his neighbour Herr Schuttmann, who had seen his silhouettes and who knew an official who knew another official, passed the information on. At the interview Gottlieb had the feeling that decisions had been made already, but when one of the men asked to see his tools he took them from his briefcase along with a sheet of paper and gave a demonstration, fashioning a tiny Siegessäule in a matter of minutes, black Victory wielding her black laurel. The man recognised the monument at once.

‘I choose only German subjects,’ said Gottlieb, and this was true; he felt no affinity with such distant marvels as the Taj Mahal or the Parthenon, wanting instead to reproduce his homeland, for the shape of a thing told what it truly was. He never invented, and he took pride in getting every detail correct: the raised hooves of the horses on the Brandenburg Gate; the slant of the artificial ruins overlooking Sanssouci; Neuschwanstein’s crow-stepped gable; Munich’s spiky carillon tower with its knight who died every day.

The man kept the paper Siegessäule, slipping it into a file. Gottlieb did not catch his name, and when the same man showed him the office that would be his on his first day, he hadn’t liked to ask. The man was talking and pointing, making sure Gottlieb knew what was expected of him, ending each sentence with questions that did not seem to require an answer. Do you understand. Is that clear. Gottlieb was to type all reports and correspondence himself. He was to start each day with a summary of his output from the previous day, listing the number of words in each category and sub-category as well as the total number of corrections made, and then he was to confirm with a signature that the waste material had been disposed of in the proper manner. The man pulled open an endless drawer as he talked, its steel bed reaching clear across the room, the side-rails recalling the guards on cots that keep infants from falling during fretful dreams. Gottlieb ran a hand along its cool and impossible length. Was this not the kind of drawer that held the nameless dead? The hanged and the drowned, the victims of exposure? It would house Gottlieb’s daily reports, said the man, filed according to the title of the parent text. If a report included multiple titles, then carbon copies of that report were to be filed according to their respective titles, with an addendum clarifying that multiple texts were included, and listing the names of those other texts in order for cross-referencing if necessary.

Gottlieb had assumed such matters would be seen to by secretaries: smartly groomed young women with neat desks and quick fingers. Perhaps, he had thought, he would even have such a woman assigned to him for his own use – a Silke or a Minna who always followed his instructions and for whom he would purchase small, suitable gifts on her birthday and at Christmas. She would blush when presented with these tokens of gratitude, and would not cast them to the back of a drawer all but untouched. She would not list them in a ledger as if they were soup bowls or pillowcases. She would not keep breaking them and asking him to glue them back together. She would keep the boxes they came in, filling them with love letters or seashells or dead flowers, and she would smooth the wrinkles from the paper that bore the names of elegant department stores: Hertie, KaDeWe, Wertheim; one could not argue with the quality of their wares, and besides, they were in German hands now.

‘I think there has been a miscommunication,’ Gottlieb said to the man whose name he did not know. ‘My position is Senior Retrospective Editor, Publications Division. This was in the letter.’ He retrieved the document – stamped and signed – from his briefcase, but the man waved it away.

‘Every employee at the Division takes responsibility for his own documents, even the Minister,’ said the man. ‘Nobody has access to another’s papers. It minimises risk. Words are only a means to an end.’

‘Nobody has access?’

‘Nobody.’

‘So my daily reports – who will read them?’ said Gottlieb.

‘As I said, it minimises risk.’ The man removed the cover from the typewriter and set it aside, gesturing to the machine as if introducing a guest of some standing. Gottlieb stared at its rows of black keys, which were not even in alphabetical order, and the man, who seemed to understand, said, ‘It is not a difficult instrument to master.’ Gottlieb thought of his Onkel Heinrich’s accordion with its many clicking buttons, its papery throat; he thought of his uncle’s eyes closing as he picked out tunes from memory, and he remembered his own stumbling fingers getting every note wrong as the thing slumped and groaned in his grasp and his mother shook her head and said there is no music in the boy. Gottlieb felt short of air, and the man was leaving him now, leaving him to begin his work, and there were so many questions he should have asked and had not.

Is it really two years since that first uncertain day? Why, he hardly gives his reports a second thought any more; they almost type themselves. He is fortunate, he knows, that the Division granted him a position. They saw something in him; some secret seed that took root and spread into his every hidden corner. There is a forest within him now, and it is full of sounds you will hear nowhere else these days, and the sounds perch lightly on the branches, and flit beneath the dark canopy, and sing and sing.

He takes up his scalpel: In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with , and the Word was .