Baby Gatekeepers

Approaching the end of her study, Pākehā publishing student Madison Hamill reflects on her place in an industry that has been described as a ‘white castle’.

Approaching the end of her study, Pākehā publishing student Madison Hamill reflects on her place in an industry that has been described as a ‘white castle’.

My name is Maddy. I’m 24 years old. I belong to a class of 17 female and one male, mostly Pākehā, publishing students in the only accredited publishing course in New Zealand. One day we will run the industry, we joke – we’ll be tycoons like Miranda Priestly in The Devil Wears Prada. “We’ll be co-CEOs,” my classmate Stef tells me. “You’ll be the kind of boss that scribbles directives on napkins and I’ll take those napkins, and then,” she pauses, “I guess, throw them out and do whatever I think best because we always agree anyway.”

This is true. Stef and I often argue about editorial decisions for several minutes before realising we’ve been on the same side the whole time. Which is not to say we are alike. Stef likes watching sports. I’m not sure which ones because my brain has this glitch where it turns off any time someone mentions sports. I adore Beyoncé, who Stef thinks is overrated. Still, in many significant ways, we are alike. We’re cis-gendered. We’re healthy and able-bodied. We’ve never experienced poverty. And we’re white.

Instead of rejecting it, I romanticised the language ... This was ‘culture’, I thought, and I didn’t have any.

I went to a high school that prided itself on having an ethnic distribution that almost perfectly matched that of the country as a whole. In retrospect it seems counterintuitive to have pride in being so very average. It was widely known that we had strong Māori and Pacific communities and a thriving kapa haka group. Sometimes an important-looking rangatira came to our school assembly and talked for a long time in Māori. Some of the girls in my class complained about this amongst themselves, saying they shouldn’t have to sit through an assembly in a language they didn’t understand. I said nothing. A couple of lessons on the Treaty weren’t really enough to build a constructive counter-argument. But I liked to listen to him speak; I liked the music the language made. Instead of rejecting it, I romanticised the language. I imagined I could feel the power of his words even though I didn’t understand them. I was secretly jealous of the girls who knew te reo. This was ‘culture’, I thought, and I didn’t have any. My own culture was invisible to me.

One day people started talking about the university scholarships. I guess it was a subject of some tension that there were scholarships for people of Māori descent. “Why do they get special scholarships?” other students started asking.

“They’re intimidating,” one girl said, “the way they walk through the corridor. They think they own the place. We shouldn’t have to feel intimidated.” You could tell she had worked up to saying it. It was the sort of thing we weren’t supposed to say. Now that someone had said it, others started agreeing, and then it all came out to one of our teachers. Even though I watched in silence, I could see that it all burned with a thrilling sense of activism, as if they had suspected the whole time that they were the real victims and had only now been able to voice their truth.

Again, I said nothing. My sense of disagreement with these statements was vague and without vocabulary. They kept saying they deserved to express their opinions. They seemed to feel they’d been silenced.

“But don’t you think it’s good that these Māori girls have a safe space to express their identity?” said our teacher.

“But what about our identities?” one of the Pākehā girls said. And that seemed too uncomfortably close to thoughts I’d had myself. What were our identities? We so wanted to have them, and with that came the urge to disown the violence of our inherited positions. Wasn’t the past in the past? Weren’t we all equal now? Of course, it wasn’t, and we weren’t, but I could see that to them it didn’t feel that way, and I kind of got it.

It was only much later that I began to think about how it might have affected those girls in a larger way, what it might mean to experience a lifetime of hearing those kinds of racist conversations.

This was the first time I’d thought much about my privilege, and almost all the people participating in the discussion were Pākehā. I remember wondering if the Māori girls knew the way the Pākehā girls were talking in another classroom, and if it made them feel angry or insecure. But it was only much later that I began to think about how it might have affected those girls in a larger way, what it might mean to experience a lifetime of hearing those kinds of racist conversations.

Stef has vague memories of listening to similar conversations about the scholarships in her own schools. She describes a familiar backing track of white confusion accompanying a high-school career in which she otherwise didn’t think about her privilege much at all. She moved around a lot, but always with the certainty that there was somewhere to go, and that she would go to a ‘good school’, which seemed to mean wealthy and Catholic, although the family was not religious.

We entered the adult world surrounded by our high-school friends. We studied in academic environments that fostered Pākehā values, and even though we were educated and interested in the world, even though we travelled and volunteered and did nothing intentionally to box ourselves in, most of the people in our social circles were not vastly different from us in their privileges.

We are starting to question whether the bird’s-eye view is a lie and we are in fact just two more in a crowd of well-intentioned opinion-havers.

Now we are learning to be publishers. We’re tasked with publishing writing by or about people who come from different social worlds, who don’t share those familiar privileges. Suddenly it is our job to participate in the conversation on the way race, class, gender and sexuality are represented in our literature. We are well-read. We are articulate. And inasmuch as identifying prejudice can be likened to finding Wally in a bird’s-eye view of a street parade full of good intentions, we are pretty good at it, as our liberal education has prepared us to be. But we are starting to question whether it is really like that at all, whether the bird’s-eye view is a lie and we are in fact just two more in a crowd of well-intentioned opinion-havers. Whether prejudice is in fact more like a system, in which we are all implicated.

Last year I wrote a collection of essays for my creative writing masters, and every time an essay got workshopped, I saw something new in it. The way I would mention the ethnicity of a Sāmoan and then a Māori person but neglect to describe the ethnicity of a Caucasian woman in the same scene, or the way I would guess at people’s thoughts in a way that reinforced a stereotype. Every month that passed I was learning something new about the way I saw the world, and the more I learnt the less, I realised, I knew.

In the manuscript Stef and I have been editing together for our publishing course, there is a character who is homeless. He is compared to a wild dog. We found ourselves having to make the judgement that this particular dehumanisation was not being used to show the narrator’s prejudices, but was instead coming from some unchecked idea that existed before the writer put pen to paper, an idea that’s been implicit in our culture since before the birth of capitalism, that the homeless man is more animal than others by virtue of his homelessness. When we discussed the problem with the author, she thanked us for picking up on something that was unintended. But we knew that in every project there was probably more we’d missed, more we did not have the authority to change and still more decisions made before we were even handed the manuscript; decisions about which books we worked on and which we never saw. We are not yet true gatekeepers, after all. Our power is entirely subject to the choices of those in command.

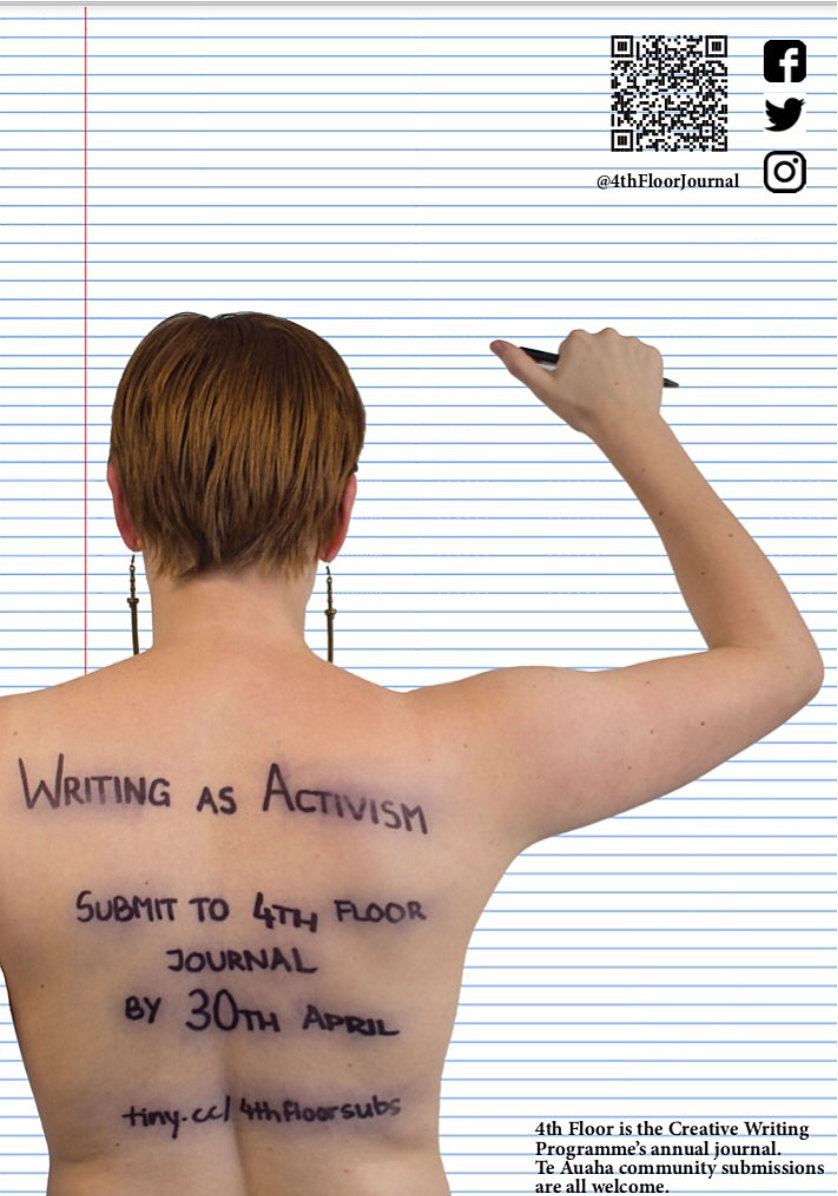

Every project comes with something new to grapple with, and a limit to how much we can do. Stef and I have been charged with marketing the 4th Floor Literary Journal this year. It’s an annual publication of new writing from people who’ve come through the Whitireia Creative Writing Programme and others in the wider Whitireia community. Guest editor this year is Cassandra Barnett (Ngāti Raukawa, Ngāti Pākehā), a writer and academic who is passionate about addressing problems of power in colonial contact zones. The theme is Writing as Activism. We met with Cassandra to talk about the concept. We agreed we didn’t want it to be all placards and battle cries. There could be other kinds of activism. Acts of examining oneself or challenging the traditional forms of expression. Cassandra was full of new ways of thinking about things.

Wanting to reach beyond the scope of our mailing list, Stef and I decided to run a poster campaign to reach as many on-campus writers as possible. We needed a striking image for our poster. How can writing be activism? we asked ourselves. How could we encapsulate the concept of writing as activism in one image? Everything about protests or real politics seemed either clichéd or too limiting. We didn’t want people putting activism in a box. It was the end of a long day and we were over-caffeinated, so we bounced ideas off each other rapidly, balancing on office chairs to write them up on the whiteboard.

“Well, I write to express emotions, because I feel like it makes them real and then I can deal with them,” said Stef. That was a sort of activism, we agreed, a way of writing to activate oneself.

“Sometimes,” I said, “writing is like walking around naked in a public space. Because making private things public makes them normal and the definition of normal needs to be expanded.”

“We could do some nudes of you walking around Wellington.” Stef suggested.

Instead, we decided to write our ‘call for submissions’ on my naked back in Sharpie and photograph me with my back to the camera, arm raised in a defiant fist, clicking a pen. We had the perfect white backdrop in our classroom, and our classmate Dave had a camera. So the next day I brought nipple covers to class and, at lunch time, we went to the bathroom to write the words “Submit to 4th Floor” and a URL on my back.

The words smudged slightly because I’d had to put my top back on while we waited for our classmates to finish their meeting with visiting clients. But when we put the poster together, we thought it worked. “You look strong,” Dave said.

So when Cassandra rejected our poster, my private reaction was defensiveness. “Apart from the slightly fuzzy writing,” she said, “there’s an issue with inclusivity. Some will see whiteness and assume it’s not for them.”

We hadn’t thought of that and at first it seemed over-sensitive. Would anyone really think that? We listed excuses to each other. We didn’t have a choice of models. Almost everyone in our class was white and those that weren’t hadn’t volunteered themselves to pose topless. We didn't have the budget to pay a real model. There was room for only one figure in the poster. But eventually we could see that Cassandra had a point.

For people who are white, the colour of my skin is information that the brain blurs out, makes invisible. We can automatically assume that the journal is ‘for us’ – that we’re allowed in, unless it says otherwise. But not everyone has that privilege. Some might have to ask themselves when they look at our poster, “Is this journal going to welcome me and my perspective? Will it be a safe space for me? Will I be a box on a diversity checklist?” It’s easy to forget that two people looking at the same thing don’t see it the same way.

In Lani Wendt Young’s lecture for Read NZ Te Pou Muramura (formerly the NZ Book Council) this year, she talks about gatekeeping in the New Zealand publishing industry. She describes a white castle manned by gatekeepers who think they can see what those in the wilderness can’t, and to know what they don’t know; who open the door only to those with ‘the right credentials’. “Its white walls are built high and strong,” she says; “they hold back the tangle of forest that threatens to encroach on its territory.”

Our own class’s ethnic and gender makeup does nothing to repudiate this image, and we know we’re nothing unusual. “Publishing is white and female,” says Young. But, characteristic of the impenetrable castle Young describes, the New Zealand publishing industry doesn’t have readily availabile statistics to offer, so we can only look at other countries like North America, where, “at the executive level, publishing is 86% white, 59% female, 89% heterosexual and 96% normatively abled.” And who are the authors who are being let in to the castle? Well we do know that here in Aotearoa, they are 91% white. And that affects the characters that are written.

In the title essay of her collection All Who Live On Islands, Wellington essayist Rose Lu writes about growing up as a Chinese New Zealander, without being able to see herself in the books the books she read. “It provokes strange reactions in us, to be almost invisible in the stories we read,” Lu writes. Author Graci Kim said at a talk recently that after writing a story about her family when she was a child, her teacher had taken her aside and asked why the family had blonde hair and blue eyes. It had never occurred to Chan that books could have Asian characters.

This problem extends to other aspects of identity. Growing up, not having books that featured minority sexualities meant that I had a very shallow understanding of what sexuality was. None of the characters I came across in books or on TV were like me in that respect, and so of course I thought there was something wrong with me, and I pretended to be like everyone else. Invisibility breeds invisibility.

When Stef and I heard Young’s lecture, we realised we’re on the inside of those castle walls now. We are baby gatekeepers. We’re being trained to one day choose whose writing gets published, what’s okay to say and what gets questioned, picked apart or edited out. Will it be our job to make sure a diverse community of people is making those choices with us, or should we be trying to build a different type of structure altogether? One with no moat or drawbridge?

One of our classmates, Olive, was lucky enough to intern at Huia and she said that she’d learned a lot about drawing the line between correcting technical errors and tone-policing. One of the staff there had explained that Indigenous writers often get edited by white editors who just can’t pick up on the nuances of Indigenous politics.

We met up with Cassandra to pick her brains on how she’s handled being the ‘gatekeeper’ for the 4th Floor Journal.

“It’s been really awkward for me,” said Cassandra. She revealed that she’s usually on the other side of the wall, submitting things and being rejected. “It’s awful being the gatekeeper.”

“Do you think writing is always political?” I asked. I wanted to know where the line was drawn, if you could avoid difficult questions by only dealing with, say, pet-themed murder mysteries.

“Everything is political,” said Cassandra. “Language itself is political. What language has been given to us, in the country we live in, as the dominant language, is political...

“Creative works – those are the places where language gets stretched,” said Cassandra. She talked about how language is challenged by subjects that are outside of the norm. “Everyday language is not made for expressing difficult experiences. It assumes we share common experiences.” I wondered: were we politicians now?

What is reading for? Is it just to feed back to us all the things we’ve already decided are valuable?

“The people who hold the spaces where writing gets seen [have] such a power,” said Cassandra. She told us about how, when editing this year’s 4th Floor, she tried to make spaces for writing that doesn’t fit into the normal mould, even for writing that she doesn’t agree with. “You have to ask yourself, could this not also be considered interesting and valuable writing? Is this not a voice that we might benefit from reading, too? What is reading for? Is it just to feed back to us all the things we’ve already decided are valuable?”

“If the people at the centre have only ever been given this set of words, and this grammar, they can only hear with those words and that grammar. But when you start giving them different languages, it opens their ears and forces a different type of hearing, and different types of concepts come in that were never given to that person before, and once they have them, they can never un-have them.

If you’ve encountered being misinterpreted enough times, then you might just close up for a while.

“Conversely, I’ve got friends nearer the margins who have written what I think are beautiful things, and they won’t put them out there because they’re like, ‘I’m sick of the mainstream not being ready to receive this. People can’t hear what I’ve got to say, so I’m not saying it.’ And that’s sad. But if you’ve encountered being misinterpreted enough times, then you might just close up for a while... I have a lot of privilege, to have not reached the end of my tether yet on being misunderstood and judged according to certain criteria that people have already developed. I pass really well as white. I have a white education, and I can speak that educated language pretty well. Sometimes that’s useful, it’s a privilege that keeps me safe. Sometimes it’s a really big problem and I wish I could shuck it off again.”

This year’s 4th Floor Journal is not at all activism in the ‘placards and marching-down-Lambton-Quay’ sense. But the ideas under the surface are big. People are talking about climate change and environmental crises, sexualities, Queer experience and Trans experience. They’re talking about abuse experiences, body image, imperialism and cultural marginalisation, including things like being Indigenous, being diaspora, being away from your culture or exiled. The journal is limited in that its authors are all connected to Whitireia New Zealand. Perhaps you could think of it as an attempt at a mirror into the inner lives of this particular community. Our cast of writers is diverse by some measures but less so by others, so some issues, like race, aren’t as prevalent as we might have hoped.

How can we, as ‘the future of the publishing industry’, as we’ve been called, transform what it means to ‘gatekeep’, when this term seems so intertwined with the way the industry is run?

Now that the Whitireia Creative Writing Programme is being discontinued, it’s unclear how much longer the 4th Floor Journal will survive. This might be its last year. It feels like a lot of pressure to make sure this year’s journal has an impact.

And beyond the 4th Floor Journal, how can we, as ‘the future of the publishing industry’, as we’ve been called, transform what it means to ‘gatekeep’, when this term seems so intertwined with the way the industry is run? Somewhere well above powerlessness but far below the authority we extend to our future selves in our dreams, we are struck by how easily passivity can turn us into tools of an ableist, capitalist, racist, transphobic, heteronormative patriarchy.

“My sort of cheap solution,” offered Cassandra hesitantly, “might just be constantly handing over to another person. Having guest editors all the time. Constantly inviting someone who will invite a different community so that different voices are getting that chance to come in and be seen and heard – while we work on transforming or dismantling the whole establishment!”

The problem seems daunting, but not because a solution seems impossible. It’s daunting because it requires more than just one journal and more than just the expertise that I, Stef and our classmates have to offer. There need to be more journals and more publishing imprints that cater to more communities – with people from those communities at the helm – and that are intentional about valuing what their authors are saying as well as how they say it.

Feature image: rocor / Flickr.

Other images supplied by Madison Hamill.

An earlier version of this article misattributed the quote from Graci Kim to Weng Wai Chang. We apologise for the error.