Black Authors: A Reading List

10 books we love by Black authors.

One of the ways that we can support Black people as non-Black allies is in consistently amplifying their voices: in art, in person and in life, and not just when their deaths circulate the news feeds. The publishing industry (which includes us) consistently under-represents Black voices. There are Black artists within our industry and worldwide who are being failed, who are not given due accolade, opportunity, response and acclaim.

We have chosen ten books by Black authors that are some of our favourites reads, with short reviews from each of the staff writers and editors at The Pantograph Punch. Some titles are academic, some are inspiring and some are just plain fun. Hopefully you can introduce a couple new pukapuka to your shelves and help to bump the sales of Black publications on bestseller charts, no matter the genre. Don’t forget to support bail funds and anti-racist movements along the way.

Becoming, by Michelle Obama

Becoming, by Michelle Obama

At the centre of the bookstore, a Black face smiled back at me, with manicured hands and eyes emanating strength and warmth. It stood out because, let’s face it, there are far too few Black faces on the covers of bestsellers. I turned it over, pulled back my shoulders and walked to the red-topped counter with the sizable hardback book I still keep close as some kind of talisman. Michelle Obama, is of course, the wife of Barack Obama, the previous democratic president of the United States of America. The woman herself is a household name, arguably as famous as her husband.

Becoming is an extraordinary account of the life of a Black girl growing up with her family in a cramped apartment on the South Side of Chicago. Although her family were not wealthy, they had a loving home life, and her working-class parents passed on their drive to succeed, fuelled by sacrifice. Michelle went to law school at Princeton (where her white roommate moved rooms because she was Black), and eventually joined the law firm where she first met Barack. During his presidential campaign, Michelle came under fire from the media for being too forceful and strong with her messaging as a Black woman.

Becoming is authentic, truthful and engaging. More than a couple of times as I scanned the words, I felt a tightening of my chest and blurring eyes. There is a bond of solidarity to be had between those who have felt the cold grip of oppression. Somehow Michelle has managed to rise above the racism levelled at her, a Black woman carving out a life in a space called ‘The White House’. As I re-read the final sentences, I am awash with a feeling of complete empowerment. “It’s not about being perfect. It’s not about where you get yourself in the end. There’s power in allowing yourself to be known and heard, in owning your unique story, in using your authentic voice…. This, for me, is how we become”. Michelle’s message to Black and Brown women everywhere is this: If I can become, you can too. – Ataria Sharman

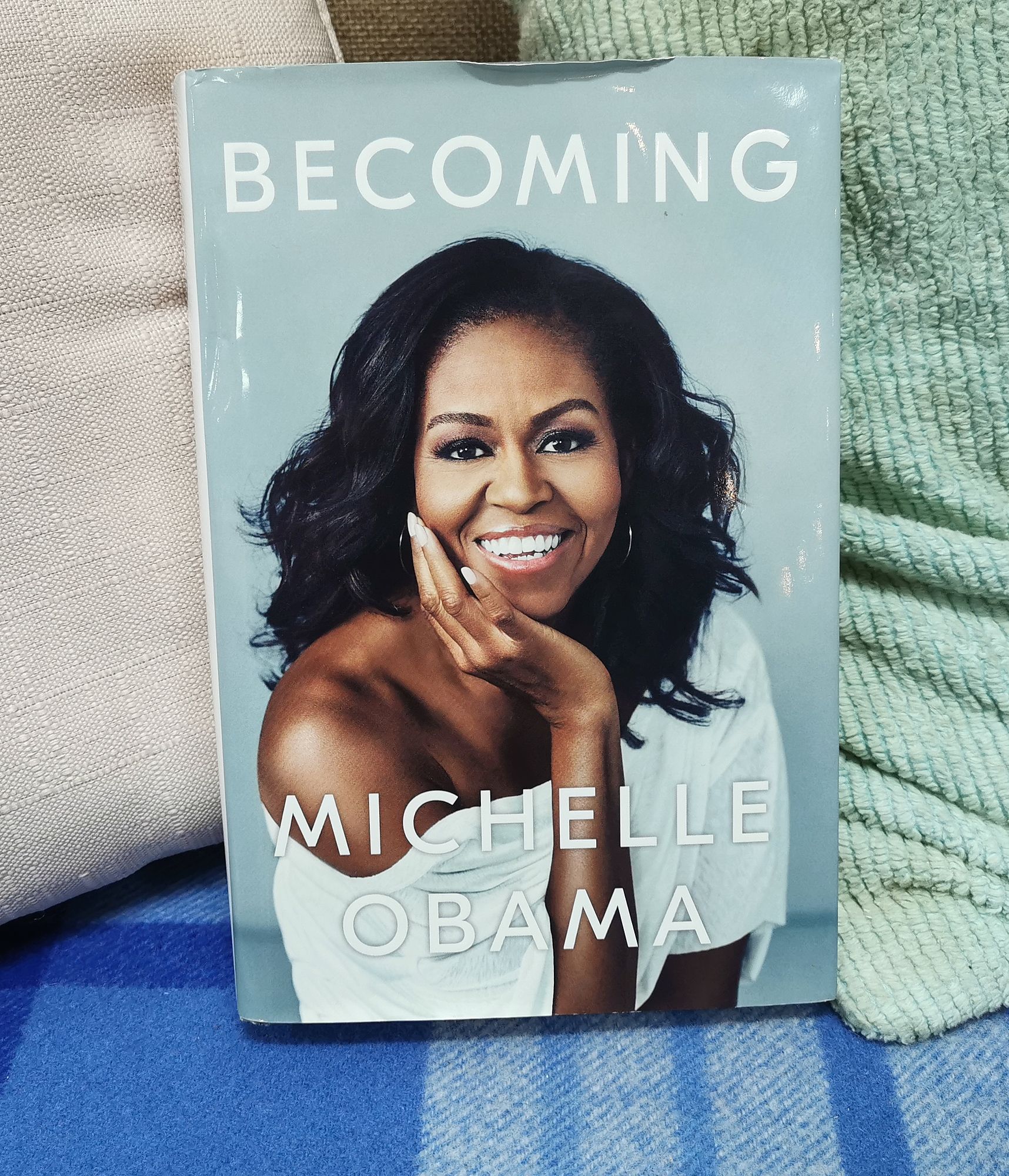

Blak Brow: The Blak Women’s Edition, published by The Lifted Brow

Blak Brow: The Blak Women’s Edition, published by The Lifted Brow

Last year, with thanks to The Māori Literature Trust, I found myself at the 2019 Sydney Writers Festival. Before my mentorship flew me there, I didn’t even know that literary festivals existed. I stood with five other Māori writers in the ticket line, surrounded by a sea of white faces. Only one event that we saw was made up of Indigenous speakers. As Māori and wāhine Māori, we had to go and tautoko our whānaunga, and that’s how we discovered Blak Brow: The Blak Woman’s Edition.

The event featured a panel of Indigenous Australian women, talking about their collective edition of writings. Put together by a collective (Paola Balla, Karen Jackson, Kim Kruger, Pauline Whyman and Bridget Caldwell), Blak Brow: The Blak Women’s Edition is a publication by Australian non-profit literary organisation The Lifted Brow.

Our ears devoured their kōrero as they spoke about the importance of community, the work of Karen Jackson (an influential Blak academic and activist) and their editorial process. They shared tales from the Moondani Balluk kitchen at Victoria University, “where Blak women activists and Aunties tell stories of community, culture and being Blak in a White World”. One of the contributing writers who sat on the panel had previously been imprisoned. Her impassioned kōrero on the incarceration rates of Blak women in Australia made me wipe tears from my cheeks. I felt her mamae as though it was my own and then realised, it was my own. The same thing is happening here in Aotearoa.

After the panel, we wandered over to meet the panelists. I got to kōrero with the Managing Editor Bridget Caldwell, who signed my copy of Blak Brow. I felt like a fangirl, but really I was in complete awe of these sovereign warriors. Blak Brow: The Black Women’s Edition is a deeply moving print magazine with a diversity of writing forms including interview, personal essays, poetry, art exhibition and even a pop quiz all crafted and curated by Blak women. – Ataria Sharman

Don’t Call Us Dead, by Danez Smith

Don’t Call Us Dead, by Danez Smith

The first sequence in Danez Smith’s 2017 poetry collection Don’t Call Us Dead (Graywolf Press, 2017) imagines an afterlife for Black men murdered by police (“dead is the safest i’ve ever been. / i’ve never been so alive”). In this world, Black men“go out for sweets & come back” and sing trap-god hymns for the men who still, even in the afterlife, scan for “bonefleshed men in blue”. The sequence speaks to grief and absence, but also to love and freedom (“outside our closet / I found a garden / he would love it here / he could love me here”). The rest of the collection continues to address the experience of being both Black and queer in America (“Some of us are killed / in pieces, some of us all at once”). The poem ‘Dear White America’creates a matrix of macro and micro aggressions by way of relentless enjambment and long prose lines to illustrate the interconnected web of racism in America (because you put an asterix on my sister’s gorgeous face! call her pretty (for a black girl)!). Another poem, ‘& even the black guy’s profile reads sorry, no black guys’, addresses internalised racism in the gay community (imagine a tulip, upon seeing a garden full of tulips, sheds its petals in disgust). The collection ends on the image of Emmett Till, being summoned back to the shore from the ocean; every Black person to ever exist, there to meet him.

On the back cover, there is a black and white photo of Danez – their trigger finger held against their temple. Beneath the photo is a line in their bio note that is as poignant and devastating as any line of poetry in the collection (“Smith lives in Minneapolis”). It makes returning to this collection at this point of time particularly heartbreaking and urgent. – Tayi Tibble

Don’t Let Me Be Lonely, by Claudia Rankine

Don’t Let Me Be Lonely, by Claudia Rankine

Don’t Let Me Be Lonely is the predecessor to Citizen, the book that secured Claudia Rankine’s well-deserved place as one of America’s best writers. Citizen, about Black visibility and police brutality swung at me with full crimson force, but it’s Don’t Let Me Be Lonely, a softer meditation on isolation that percolates in the back of my brain. The lyric form that Rankine uses in both is innovative for its time and today, staggering between prose, anecdote, poem and visual album.

Perhaps I love this book because it delivers a simple fact with stunning acuity: that we expect Black people to be angry but not to be lonely. We don’t register that living with the brunt of systemic racism is a wholly numbing and alienating experience, one in which reality suffers for not being able to rely on your society, friends and neighbours for the common protection we take for granted. Activists know how to talk about rage but we don’t talk so much about the side effects of rage (loss and apathy). Rankine does, and did. Her writing on racism, pill prescriptions, life-as-a-product-on-television dissolves borders of cultural criticism and shows the terrifying interconnectivity of societal failings. I am struck by how well Rankine articulates the ravaging effect of being visible but not being seen; being alive and yet numb to the hand that swings to hit you. It reminds me that the conversation around wellness in Black and POC community isn’t nearly prioritised enough. It all feels hauntingly prescient. – Vanessa Crofskey

My Sister, The Serial Killer by Oyinkan Braithwaite

My Sister, The Serial Killer by Oyinkan Braithwaite

Nigerian-UK author Oyinkan Braithwaite’s debut novel, My Sister, The Serial Killer, is a thrilling read, following sisters Korede and Ayoola – one of whom can’t stop killing her suitors. This book feels a lot like its cover: punchy, bold and with humour as sharp as a knife-edge. A sexy rebound from books I couldn’t stop putting down, I very much liked the fast pace, unique storyline and refreshing prose.

With Black women often positioned on page and screen in the role of the tragic suffering victim, this is a sharp response to assumptions of who-inflicts-violence-on-whom, how a person might choose to reclaim power and how far we are willing to go to help the ones we love. I’m still grappling with its moral decisions days later, I loved the fact that it decentred assumptions of what one might expect from a story set in contemporary Nigeria.

– Vanessa Crofskey

Natives: Race and Class in the Ruins of Empire, by Akala

Natives: Race and Class in the Ruins of Empire, by Akala

Akala is a man of many talents, and a master of all of them. You may have come across his music featuring blistering social critique delivered through razor sharp flows; you may have seen his Oxford Union address on Black history forgotten or ignored; you may have seen him on TV, schooling Piers Morgan, or busting prejudice in the literary canon in his TEDx Talk. Whatever the context and topic at hand, Akala is an intellectual and artistic force.

In his book, Natives: Race & Class in the Ruins of Empire, Akala uses his experience of growing up as a mixed race boy in Camden as an autobiographical structure for exploring the historical and political forces that have entrenched racism in British social systems, impacting Black life today. Akala brings academic rigour to his arguments on education, the police, class, identity, while charting the course of his own growth and empowerment. It's that combination which makes his storytelling so compelling.

He ends the book in a way that now seems particularly prescient: the answers to the questions we face will be shaped “not just by politicians and billionaires, but by millions of supposedly ordinary people like you and me who choose whether or not to engage in difficult issues, to try and grasp history, to find their place in it, and who choose whether to act or do nothing when faced with the mundane and mammoth conflicts of everyday life.” – Hannah Newport-Watson

What We Lose, by Zinzi Clemmons

What We Lose, by Zinzi Clemmons

Zinzi Clemmons’ debut novel What We Lose conveys the absolute disjointedness of grief. Clemmons is an innovative writer and the form of the book reflects this, with fragments and vignettes that frequently jump in time. Clemmons’ narrator, Thandi, is not a warm character – she is imperfect and at times depressed; not all readers will connect with her. But that’s another important truth at the heart of this novel, that grief doesn’t magically make us likeable.

What We Lose was a well-deserved critical success (Vogue called it “the debut novel of the year”). Although the book centres emotionally on grief and parenthood, reflections on race, identity and belonging also splinter throughout. In one such moment, Clemmons writes: “I’ve often thought that being a light-skinned black woman is like being a well-dressed person who is also homeless. You may be able to pass in mainstream society, appearing acceptable to others, even desired. But in reality you have nowhere to rest, nowhere to feel safe.” Whether you’ve lost a person close to you or not, this book will move something in you. – Hannah Newport-Watson

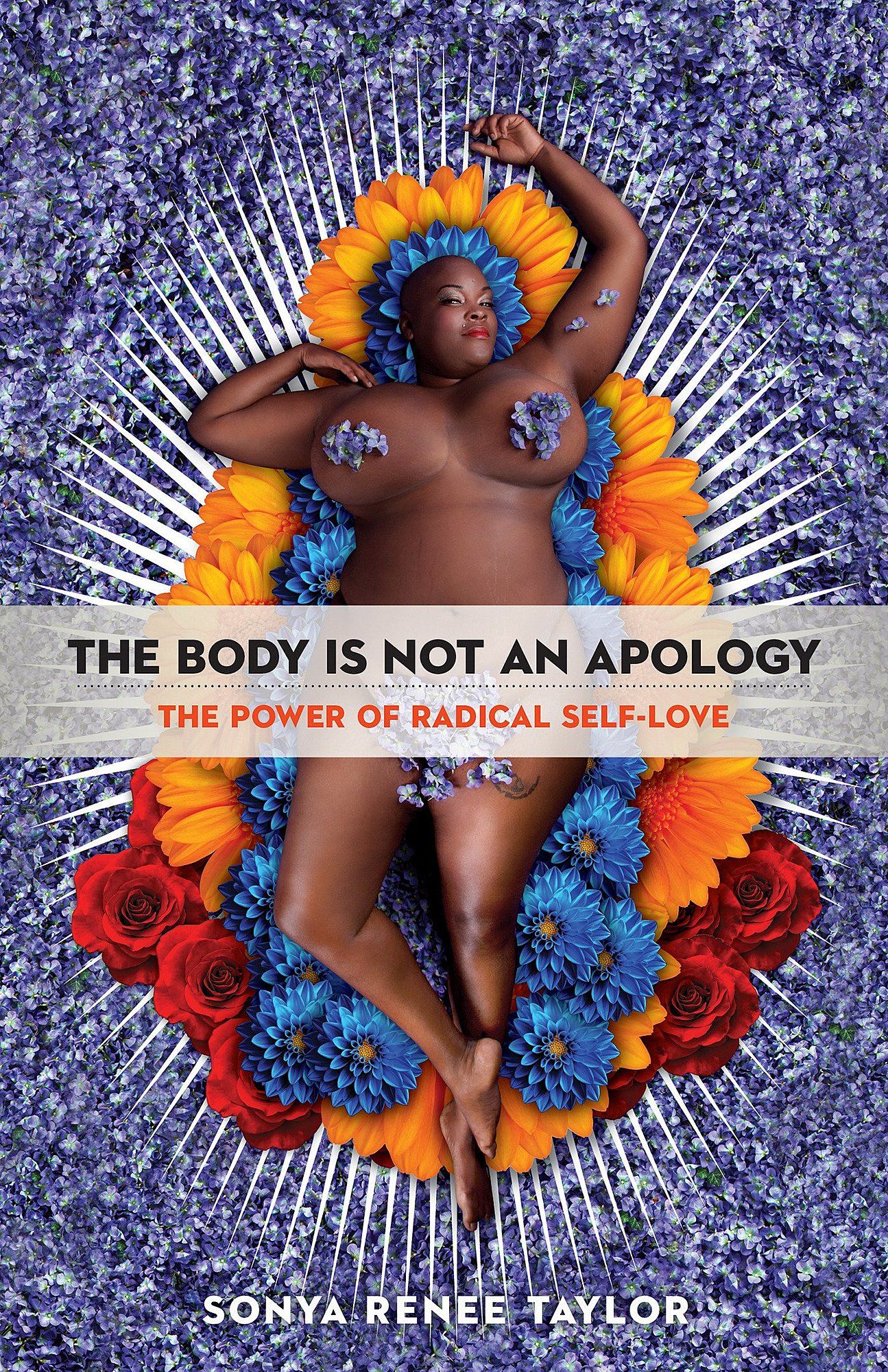

The Body Is Not an Apology: The Power of Radical Self-love by Sonya Renee Taylor

The Body Is Not an Apology: The Power of Radical Self-love, by Sonya Renee Taylor

Two years after my first reading of The Body is not an Apology: The Power of Radical Self-love I flick through it again and land on the sentence, “When we hear someone’s truth and it strikes some deep part of our humanity, our own hidden shames, it can be easy to recoil into silence.” The idea for silence today doesn’t feel like an option. As Taylor tells us, oppressive structures thrive off of our inability to make peace with our relationships to our bodies. Healing those wounds thus becomes a transformative and radical act.

Before reading The Body is not an Apology I knew very little about what radical self-love meant, let alone what it felt like. This book not only introduces the idea of radical self-love in an accessible and personable way, it also provides a blueprint for transformative ways to heal. – Lana Lopesi

Thick and Other Essays, by Tressie McMillan Cottom

Thick and Other Essays, by Tressie McMillan Cottom

Thick and Other Essays by Tressie McMillan Cottom sits in a long line of excellent scholarship by Black women who continually transform ways of thinking, radically shaking up both literary and academic canons. How grateful we should be to have access to these words. McMillan Cottom decisively interrogates beauty, capitalism, race and politics through the lens of Black feminism. With grit and a sharp intellect, these essays provide a grimacing look into contemporary America. As McMillan Cottom writes, “this is the best it has ever been to be black in America and it is still that statistically bad.” Just buy the book, tbh. – Lana Lopesi

Voyage of the Sable Venus and Other Poems, by Robin Coste Lewis

Voyage of the Sable Venus and Other Poems, by Robin Coste Lewis

Robin Coste Lewis’s The Voyage of the Sable Venus is a tripartite book, the titular poem making up all of part II: an epic written entirely from the names of artworks that feature Black women. No title is changed. No title, bar once, is repeated. Punctuation is changed and utilised to alter meaning and interpretation. It is as hard-hitting as you would expect, but it’s also very difficult to describe the feeling of reading it. It’s physical.

Lewis isn’t so much giving voice to these fragments of women as they appear through art (a head, a face, a leg). She’s carrying them. Or maybe it’s not so much carrying as sailing with them, alongside the ‘Sable Venus’, to a destination she doesn’t yet know. As you read on, you begin to understand that perhaps this journey also works the other way around, as Lewis writes: “Instead of going on shore and returning with more images, more forms, I was the broken body who would be getting off and not coming back. I was the one who had been rescued.”

Through the act of researching and writing, Lewis is not only saying I see you, to the many named and unnamed, Untitled Black women she met through the annals of art over millennia; she saw that they were there all along, “looking right back at you.” The other poems in this 160 page book that aren’t ‘found’ poems in the sense, are creamy, mouthfuls of poems. They drip gold. They’re poems that love form, and love to fuck it up too. They’re songs of seeing. The ending of ‘Second Line’ a tribute to the author’s father, is just so rich:

I could smell the world all over you, Daddy.

You gave it to me – a fresh, sharp walnut – pungent and coy.

You cracked it, plucked out its intelligence,

Then dropped it in my hand: this deep black joy.

– Faith Wilson

This list is a launching point for those stuck on what to read, but is by no means exhaustive. We encourage you to do your own research and look for Black authors in your local libraries and bookstores. If you are looking for further reading lists, the Spinoff has a great Anti-Racist Reading List of seminal Māori texts, as does Readings Australia with this Aboriginal Lives Matter reading list.

Most book titles are available at local and national bookstores such as Unity Books, Timeout, VicBooks and Whitcoulls. The Blak Brow: Black Women’s Edition is available for purchase through The Lifted Brow website.